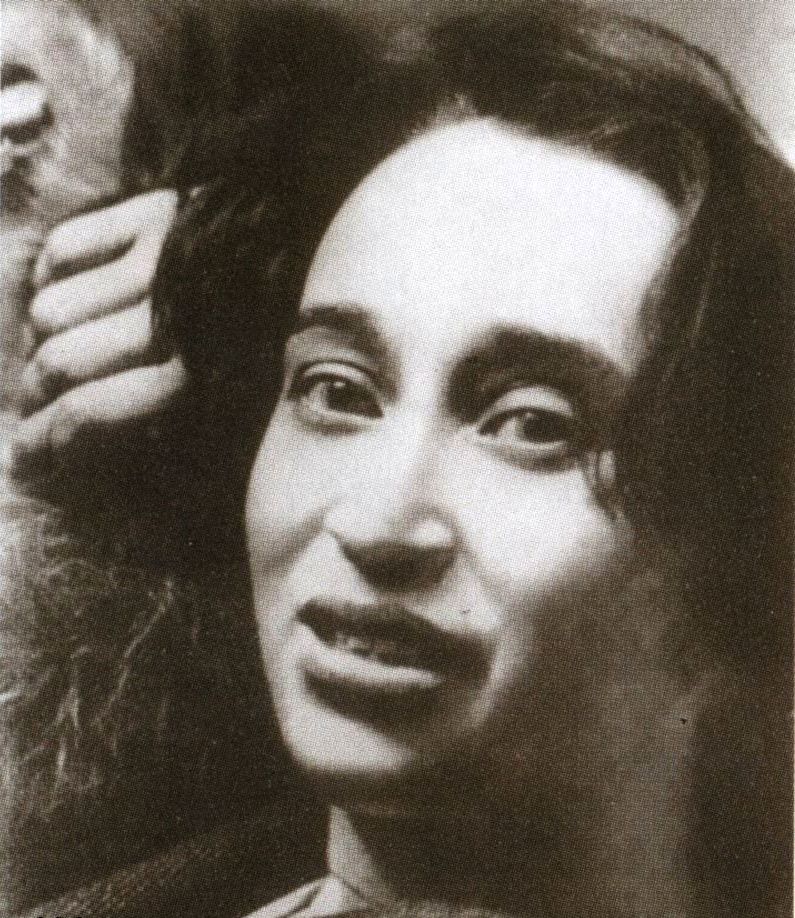

Nadjezjda Jakovlevna Mandelstam (Russisch: Надежда Яковлевна Мандельштам, geboren als Nadjezjda Jakovlevna Chazina (Russisch: Надежда Яковлевна Хазина) (Saratov, 31 oktober 1899 – Moskou, 29 december 1980) was een Russisch dissidente schrijfster en echtgenote van de dichter Osip Mandelstam.

Leven

Mandelstam groeide op in een Joodse familie in Kiev, waar ze kunstgeschiedenis studeerde.

In 1921 huwde ze met Osip Mandelstam. Osip werd in 1934 gearresteerd en samen met Nadjezjda verbannen vanwege zijn epigram met een voor Stalin beledigende inhoud.

Na Osips tweede arrestatie en overlijden in een doorvoerkamp in 1938 leidde Mandelstam een zwervend bestaan om arrestatie te voorkomen, waarbij ze regelmatig van adres en baan wisselde. Ze zag het als haar levenstaak de poëzie van Osip te bewaren voor het nageslacht. Ze leerde daarvoor het oeuvre van haar man uit haar hoofd.

Ze was, evenals haar man, bevriend met Anna Achmatova. Ze overleefde de Tweede Wereldoorlog met Achmatova in Tasjkent.

Memoires

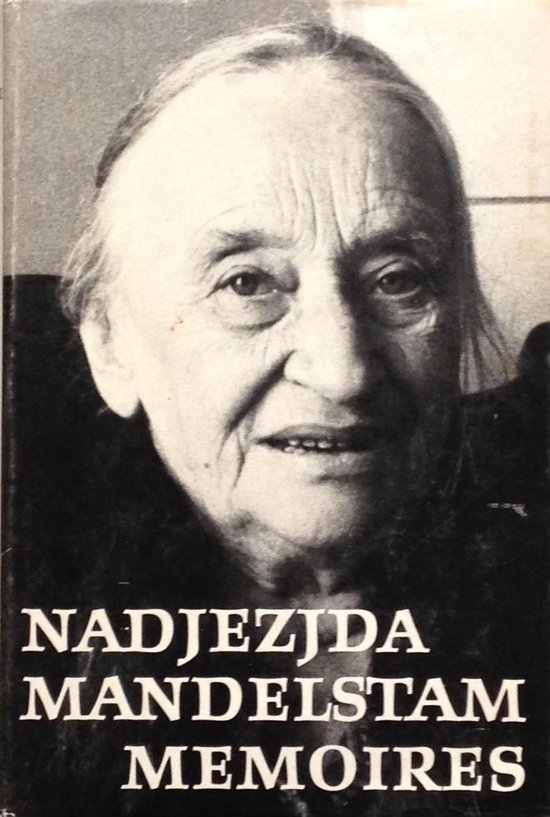

Na Stalins dood kon Mandelstam terugkeren naar Moskou en publiceerde ze haar tweedelige memoires, aanvankelijk alleen in het Westen. De boeken geven een inzicht in de levenswijze van dissidente burgers in het Rusland onder Stalin. Ze bevatten een epische analyse van haar leven en een scherpe kritiek op het verval van de sovjetmoraal in de jaren twintig van de twintigste eeuw en daarna. Iedereen kon een verklikker zijn of worden. Iedereen die het regime onwelgevallig was kon worden veroordeeld. Een leven in volstrekte anonimiteit, of zoals Mandelstam zegt, door zo stil te zijn als water en zo kort als gras, leek de beste mogelijkheid om te overleven.

Naar aanleiding van de angsten die haar man moest doorstaan, en die leidden tot een zelfmoordpoging van zijn kant, kwam Nadjezjda tot een interessante beschrijving van het creatieve proces van een dichter en de psychische kwetsbaarheden die daarmee samenhangen. Ze legde er de nadruk op dat een gedicht ontstaat vanuit het onderbewuste en niet door bewuste associatie. Het daaropvolgende zoekproces naar woorden is een proces dat de dichter geheel in beslag neemt.

In 1979 droeg Mandelstam haar Osip Mandelstam-archieven over aan de Princeton University. Ze stierf op 81-jarige leeftijd.

Monument

In de Nadezjda Mandelstamstraat in Amsterdam staat het gedenkbeeld Monument voor de liefde voor Nadjezjda en Osip Mandelstam, gemaakt door Hanneke de Munck en Chatsjatoer Bjely. Naar aanleiding van de onthulling van het gedenkbeeld in september 2015 verscheen tevens een gelegenheidsuitgave, Monument voor de liefde – Osip en Nadezjda Mandelstam, met zeven gedichten van Osip Mandelstam, in een vertaling door Nina Targan Mouravi.

Herdenkings-essay Brodsky

Joseph Brodsky herdacht haar in zijn essay Nadezjda Mandelstam (1899 – 1980). Een overlijdensbericht (Nederlandse vertaling in Tussen iemand en niemand, Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 1987, pp. 150 – 161). Brodsky schreef: “In ontwikkelde kringen, in het bijzonder onder literatoren, is het zijn van een weduwe van een groot man genoeg om een eigen identiteit aan te ontlenen. Dat is in het bijzonder het geval in Rusland, waar het regime in de jaren dertig en veertig met een dermate grote effectiviteit schrijversweduwen produceerde dat er in het midden van de jaren zestig genoeg rondliepen om een vakbond mee te organiseren”. Hij prijst haar als een buitengewoon krachtige persoonlijkheid.

Bibliografie

- Memoires [eerste deel van de memoires, in het Engels getiteld Hope against Hope], Amsterdam: Van Oorschot, 1971. ISBN 90-282-0260-9

- Tweede boek [tweede deel van de memoires, in het Engels getiteld Hope Abandoned], Amsterdam: Van Oorschot, 1973. ISBN 90-282-0288-9

Externe link

- (en) Mandelstam op Fembio

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nadjezjda_Mandelstam

The “Stalin Epigram“, also known as “The Kremlin Highlander” (Russian: Кремлёвский горец) is a satirical poem by the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, written in November 1933. The poem describes the climate of fear in the Soviet Union.

Mandelstam read the poem only to a few friends, including Boris Pasternak and Anna Akhmatova. The poem played a role in his own arrest and the arrests of Akhmatova’s son and husband, Lev Gumilev and Nikolay Punin.

The poem was almost the first case Genrikh Yagoda dealt with after becoming NKVD boss. Nikolai Bukharin visited Yagoda to intercede for Mandelstam, unaware of the nature of his “offense”. According to Mandelstam’s widow Nadezhda: “Yagoda liked M.’s poem so much that he even learned it by heart – he recited it to Bukharin – but he would not have hesitated to destroy the whole of literature, past, present and future, if he had thought it to his advantage. For people of this extraordinary type, human blood is like water.”

We are living, but can’t feel the land where we stay,

More than ten steps away you can’t hear what we say.

But if people would talk on occasion,

They should mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

His thick fingers are bulky and fat like live-baits,

And his accurate words are as heavy as weights.

Cucaracha’s moustaches are screaming,

And his boot-tops are shining and gleaming.

But around him a crowd of thin-necked henchmen,

And he plays with the services of these half-men.

Some are whistling, some meowing, some sniffing,

He’s alone booming, poking and whiffing.

He is forging his rules and decrees like horseshoes –

Into groins, into foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Every killing for him is delight,

And Ossetian torso is wide.

The phrase “Ossetian torso” in the final line refers to the ethnicity of Stalin, whose paternal grandfather was possibly an ethnic Ossetian.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalin_Epigram

Ian Probstein: Three translations of Osip Mandelstam’s ‘Stalin’s Epigram’

https://jacket2.org/commentary/ian-probstein-mandelstam-stalin-epigram

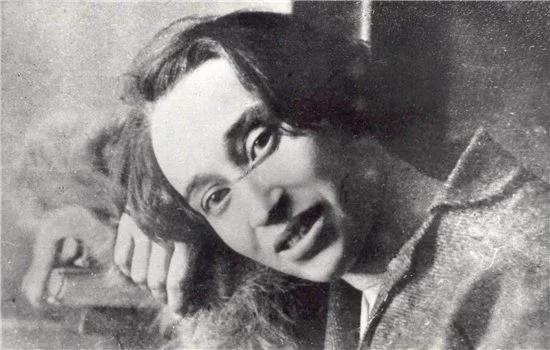

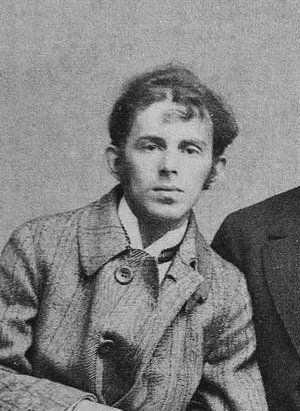

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (Russian: Осип Эмильевич Мандельштам, IPA: [ˈosʲɪp ɨˈmʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam]; 14 January [O.S. 2 January] 1891 – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repression of the 1930s and sent into internal exile with his wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam. Given a reprieve of sorts, they moved to Voronezh in southwestern Russia. In 1938 Mandelstam was arrested again and sentenced to five years in a corrective-labour camp in the Soviet Far East. He died that year at a transit camp near Vladivostok.[2]

Life and work

Mandelstam was born on 14 January 1891 in Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire to a wealthy Polish-Jewish family. His father, a leather merchant by trade, was able to receive a dispensation freeing the family from the Pale of Settlement. Soon after Osip’s birth, they moved to Saint Petersburg. In 1900, Mandelstam entered the prestigious Tenishev School. His first poems were printed in 1907 in the school’s almanac. As a schoolboy, he was introduced by a friend to members of the illegal Socialist Revolutionary Party, including Mark Natanson, and the revolutionary Grigory Gershuni.

In April 1908, Mandelstam decided to enter the Sorbonne in Paris to study literature and philosophy, but he left the following year to attend the University of Heidelberg in Germany. In 1911, he decided to continue his education at the University of Saint Petersburg, from which Jews were excluded. He converted to Methodism and entered the university the same year. He did not complete a formal degree.

Mandelstam’s poetry, acutely populist in spirit after the first Russian revolution in 1905, became closely associated with symbolist imagery. In 1911, he and several other young Russian poets formed the “Poets’ Guild”, under the formal leadership of Nikolai Gumilyov and Sergei Gorodetsky. The nucleus of this group became known as Acmeists. Mandelstam wrote the manifesto for the new movement: The Morning Of Acmeism (1913, published in 1919). In 1913 he published his first collection of poems, The Stone; it was reissued in 1916 under the same title, but with additional poems included.

In 1922, Mandelstam and Nadezhda moved to Moscow. At this time, his second book of poems, Tristia, was published in Berlin. For several years after that, he almost completely abandoned poetry, concentrating on essays, literary criticism, memoirs The Noise Of Time, Feodosiya – both 1925; (Noise of Time 1993 in English) and small-format prose The Egyptian Stamp (1928). As a day job, he translated literature into Russian (19 books in 6 years), then worked as a correspondent for a newspaper.

Silver Age poets Mandelstam, Chukovsky, Livshits and Annenkov in 1914. Photo of Karl Bulla

First arrest

In the autumn of 1933, Mandelstam composed the poem “Stalin Epigram“, which he recited at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. The poem deliberately insulted the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. In the original version, the one that was handed in to the police, he called Stalin the “peasant slayer”, as well as pointing out that he had fat fingers. Six months later, on the night of 16–17 May 1934, Mandelstam was arrested by three NKVD officers who arrived at his flat with a search warrant signed by Yakov Agranov. His wife hoped at first that this was over a fracas that had taken place in Leningrad a few days earlier, when Mandlestam slapped the writer Alexei Tolstoy because of a perceived insult to Nadezhda, but under interrogation he was confronted with a copy of the Stalin Epigram, and immediately admitted to being its author, believing that it was wrong in principle for a poet to renounce his own work. Neither he nor Nadezhda had ever risked writing it down, suggesting that one of the trusted friends to whom he recited it had memorised it, and handed a written copy to the police. It has never been established who it was.

Mandelstam anticipated that insulting Stalin would carry the death penalty, but Nadezhda and Anna Akhmatova started a campaign to save him, and succeeded in creating “a kind of special atmosphere, with people fussing and whispering to each other.” The Lithuanian ambassador in Moscow, Jurgis Baltrušaitis warned delegates at a conference of journalists that the regime appeared to be on the verge of killing a renowned poet. Boris Pasternak – who disapproved of the tone of the Epigram – nonetheless appealed to the eminent Bolshevik, Nikolai Bukharin, to intervene. Bukharin, who had known the Mandelstams since the early 1920’s and had frequently helped them, approached the head of the NKVD, and wrote a note to Stalin.

Exile

On 26 May, Mandelstam was sentenced neither to death, nor even the Gulag, but to three years’ exile in Cherdyn in the Northern Ural, where he was accompanied by his wife. This escape was looked upon as a “miracle” – but the strain of his interrogation had driven Mandelstam to the verge of insanity. He later wrote that “at my side, my wife did not sleep for five nights” – but when they arrived at Cherdyn, she fell asleep, in the upper floor of a hospital, and he attempted suicide by throwing himself out of the window. His brother, Alexander, appealed to the police for his brother to be given proper psychiatric care, and on 10 June, there was a second “miracle”, which banished Mandelstam from the twelve largest Soviet cities, but otherwise allowed him to choose his place of exile.

Mandelstam and his wife chose Voronezh, possibly, partly, because the name appealed to him. In April 1935, he wrote a four line poem that included the pun – Voronezh – blazh’, Voronezh – voron, nozh meaning ‘Voronezh is a whim, Voronezh – a raven, a knife.’. Just after their arrival, Boris Pasternak was startled to receive a phone call from Stalin – his only conversation with the dictator, in which Stalin wanted to know whether Mandelstam really was a talented poet. “He’s a genius, isn’t he?” he is reputed to have asked Pasternak.

During these three years, Mandelstam wrote a collection of poems known as the Voronezh Notebooks, which included the cycle Verses on the Unknown Soldier. He and his wife did not know about Stalin’s phone call to Pasternak until months after it took place, and did not feel safe from arrest. When Akhmatova was paying them a visit, a couple of other friends unexpectedly knocked on the door. All of them thought it was the police. This inspired the lines written by Akhmatova in March 1936:

But in the room of the poet in disgrace

Fear and the Muse keep watch by turns.

And the night comes on

That knows no dawn.

Actually, the fact that Stalin had given an order to “isolate and preserve” Mandelstam meant that he was safe from further persecution, temporarily. In Voronezh, he was even granted a face-to-face meeting with the local head of the NKVD, Semyon Dukelsky, who told him “write what you like”, and turned down an offer by Mandelstam to send in every poem he wrote to police headquarters. After that meeting, police agents ceased shadowing the couple. There is a story, possibly apocryphal, that Mandelstam even rang Dukelsky to recite poetry over the phone.

Second arrest and death

NKVD photo after the second arrest, 1938

Mandelstam’s three-year period of exile ended in May 1937, when the Great Purge was under way. The previous winter, he had forced himself to write his “Ode to Stalin,” hoping it would protect him against further persecution. The couple no longer had the right to live in Moscow, so lived in nearby Kalinin (Tver), and visited the capital, where they relied on friends to put them up. In the spring of 1938, Mandelstam was granted an interview with the head of the Writers’ Union Vladimir Stavsky, who granted him a two-week holiday for two in a rest home outside Moscow. This was a trap. The previous month, on 16 March – the day after the Mandelstams’ former protector, Nikolai Bukharin had been sentenced to death – Stavsky had written to the head of the NKVD, Nikolay Yezhov, denouncing Mandelstam. Getting him out of Moscow made it possible to arrest him without setting off a reaction. He was arrested while on holiday, on 5 May (ref. camp document of 12 October 1938, signed by Mandelstam), and charged with “counter-revolutionary activities.”

Four months later, on 2 August 1938, Mandelstam was sentenced to five years in correction camps. He arrived at the Vtoraya Rechka (Second River) transit camp near Vladivostok in Russia’s Far East. From the Vladperpunkt transit camp he sent his last letter to his brother and his wife:

Dear Shura!

I’m in Vladivostok, SVITL, barracks 11. I got 5 years for K.R.D. [counterrevolutionary activity] by the decision of the OSO. From Moscow, left from Butyrka on September 9, arrived on October 12. Health is very poor. Exhausted to the extreme. Have lost weight, almost unrecognizable. But I don’t know if there is any sense in sending clothes, food and money. Try it, all the same. I’m freezing without proper things. Nadinka, I don’t know if you’re alive, my dove. You, Shura, write to me about Nadia right away. There’s a transit point here. They didn’t take me to Kolyma. Wintering is possible.

My relatives, kiss you.

Aaxe.

Shurochka, I’m writing more. I’ve been going to work in recent days, and it’s uplifting.

From our camp, a transit camp, they send one to the permanent camp. I obviously got caught in the “dropout” and we have to prepare for the winter. And I’m asking: send me a radiogram and money by telegraph.

On 27 December 1938, before his 48th birthday, Osip Mandelstam died in a transit camp of typhoid fever. His death was described later in a short story “Sherry Brandy” by Varlam Shalamov. Mandelstam’s body lay unburied until spring, along with the other deceased. Then the entire “winter stack” was buried in a mass grave.

Mandelstam’s own prophecy was fulfilled: “Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?” Nadezhda wrote memoirs about her life and times with her husband in Hope against Hope (1970)[24] and Hope Abandoned. She also managed to preserve a significant part of Mandelstam’s unpublished work.

Marriage and family

In 1916, Mandelstam was passionately involved with the poet Marina Tsvetayeva. According to her biographer, “Of the many love affairs with men that Marina embarked upon with such intensity during this period, it was probably the only one that was physically consummated.” Mandelstam was said to have had an affair with the poet Anna Akhmatova. She insisted throughout her life that their relationship had always been a very deep friendship, rather than a sexual affair. In the 1910s, he was in love, secretly and unrequitedly, with a Georgian princess and St. Petersburg socialite Salomea Andronikova, to whom Mandelstam dedicated his poem “Solominka” (1916).

In 1922, Mandelstam married Nadezhda Mandelstam in Kyiv, Ukraine, where she lived with her family, but the couple settled in Moscow. He continued to be attracted to other women, sometimes seriously. Their marriage was threatened by his falling in love with other women, notably Olga Vaksel in 1924–25 and Mariya Petrovykh in 1933–34 Nadezha Mandelstam formed a lifelong friendship with Anna Akhmatova, who was a guest in the Mandelstam’s apartment when he was arrested for the first time, but complained that she could never be friendly with Tsvetayeva, partly because “I had decided on Akhmatova as ‘top’ woman poet”. She also complained that Tsvetayeva could not take her eyes off her husband, and that “she accused me of being jealous of her.”

During Mandelstam’s years of imprisonment, 1934–38, Nadezhda accompanied him into exile. Given the real danger that all copies of Osip’s poetry would be destroyed, she worked to memorize his entire corpus, as well as to hide and preserve select paper manuscripts, all the while dodging her own arrest. In the 1960s and 1970s, as the political climate thawed, she was largely responsible for arranging clandestine republication of Mandelstam’s poetry.

Posthumous reputation and influence

- Dutch composer Marjo Tal (1915–2006) set several of Mandelstam’s poems to music.

- In 1956, during the Khrushchev thaw, Mandelstam was rehabilitated and exonerated from the charges brought against him in 1938.

- The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation aired Hope Against Hope, a radio dramatization about Mandelstam’s poetry based on the book of the same title by Nadezhda Mandelstam, on 1 February 1972. The script was written by George Whalley, a Canadian scholar and critic, and the broadcast was produced by John Reeves.

- In 1977, a minor planet, 3461 Mandelshtam, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named after him.

- On 28 October 1987, during the administration of Mikhail Gorbachev, Mandelstam was also exonerated from the 1934 charges and thus fully rehabilitated.

- In 1998, a monument was put up in Vladivostok in his memory.

- In 2020, Noemi Jaffe, a Brazilian writer, wrote a book about his persecution and how his wife managed to preserve his work, called “What she whispers” (O que ela sussurra).

- In 2021, the album Sokhrani moyu rech’ navsegda (Russian: «Сохрани мою речь навсегда», lit. ‘Save My Words Forever’) was released in honor of the 130th anniversary of Mandelstam’s birth. The album is a compilation of songs based on Mandelstam’s poems by artists such as Oxxxymiron, Leonid Agutin, Ilya Lagutenko, Shortparis, and Noize MC.

Bibliography

Prose

- The Noise Of Time (1925, collection of autobiographical sketches)

- The Egyptian Stamp (1928, short novel)

- The Fourth Prose (1930)

- Journey to Armenia (1933, collection of travel sketches)

Poetry collections

- Stone (1913/1916/1923)

- Tristia (1922)

- Second Book (1923)

- Poems 1921–1925 (1928)

- Poems (1928)

- Moscow Notebooks (1930–34)

- Voronezh Notebooks (1934–37)

Essays

- On Poetry (1928)

- Conversation about Dante (1933; published in 1967)

Selected translations

- Ahkmatova, Mandelstam, and Gumilev (2013) Poems from the Stray Dog Cafe, translated by Meryl Natchez, with Polina Barskova and Boris Wofson, hit & run press, (Berkeley, CA) ISBN 0936156066

- Mandelstam, Osip and Struve, Gleb (1955) Sobranie sočinenij (Collected works). New York OCLC 65905828

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) Selected Poems, translated by David McDuff, Rivers Press (Cambridge) and, with minor revisions, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (New York)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) The Complete Poetry of Osip Emilevich Mandelstam, translated by Burton Raffel and Alla Burago. State University of New York Press (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1973) The Goldfinch. Introduction and translations by Donald Rayfield. The Menard Press

- Mandelstam, Osip (1974). Selected Poems, translated by Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin. NY: Atheneum, 1974.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1976) Octets 66-76, translated by Donald Davie, Agenda vol. 14, no. 2, 1976.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1977) 50 Poems, translated by Bernard Meares with an Introductory Essay by Joseph Brodsky. Persea Books (New York)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1980) Poems. Edited and translated by James Greene. (1977) Elek Books, revised and enlarged edition, Granada/Elek, 1980.

- Mandelstam, Osip (1981) Stone, translated by Robert Tracy. Princeton University Press (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (1991) The Moscow Notebooks, translated by Richard & Elizabeth McKane. Bloodaxe Books (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) ISBN 978-1-85224-126-1

- Mandelstam, Osip (1993, 2002) The Noise of Time: Selected Prose, translated by Clarence Brown, Northwestern University Press; Reprint edition ISBN 0-8101-1928-5

- Mandelstam, Osip (1996) The Voronezh Notebooks, translated by Richard & Elizabeth McKane. Bloodaxe Books (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) ISBN 978-1-85224-205-3

- Mandelstam, Osip (1991) The Moscow & Voronezh Notebooks, translated by Richard & Elizabeth McKane. Bloodaxe Books (Tarset, Northumberland, UK) ISBN 978-1-85224-631-0

- Mandlestam, Osip (2012) “Stolen Air”, translated by Christian Wiman. Harper Collins (USA)

- Mandelstam, Osip (2018) Concert at a Railway Station. Selected Poems, translated by Alistair Noon. Shearsman Books (Bristol)

- Mandelstam, Osip (2022) The Voronezh Workbooks, translated by Alistair Noon, Shearsman Books (Bristol)

- Mandelstam, Osip (2022) Occasional and Joke Poems, translated by Alistair Noon, Shearsman Books (Bristol)

Reviews

- McCarey, Peter (1982), review of Osip Mandelstam’s “Stone” translated by Robert Tracy and Poems chosen and translated by James Greene, in Murray, Glen (ed.), Cencrastus No. 8, Spring 1982, p. 49, ISSN 0264-0856

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osip_Mandelstam

It is said that a translator is like a spy: if everything is fine, the author of the original is praised and the translator is barely noticed; if not, the translator is blamed. Having that in mind, I am going to discuss several translations of Osip Mandelstam’s “Stalin’s Epigram”, which cost him two exiles and eventually, life.

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) led an unsettled life full of tribulations, wandering and exile. After his Stalin’s epigram of 1933, for which the dictator, who used to say that “vengeance is best when served cold,” never forgave the poet. Mandelstam was first sent to Cherdyn’ in Siberia, then due to protection of several powerful Communist party functionaries who were fond of Mandelstam’s poetry, the term was somehow milder: he had to live in the provincial town of Voronezh deprived of the right to live in the capital and big cities, and finally was arrested again in 1937, sent to Vladivostok labor (virtually concentration) camp where he perished in 1938. The exact date of his death is unknown; neither has the poet the grave of his own.

The original text, arranged in two stanzas, eight lines each, as if looking forward to his famous “Octaves” the first draft of which he composed in 1933 as well. Unlike the later deep metaphysical and esoteric poem, the epigram is written in overt manner with a lot of colloquial expressions, idioms, and even neologisms coined by the poet. It comprises alternating rhymed couplets (hence the translators changed the graphic appearance of the poem). The basic meter is alternating anapest, the first two lines are four-feet with masculine rhymes, the third and fourth are three-feet with feminine rhymes, the fifth and fourth are four-feet masculine again and so forth. Meter and rhyme are very important for Mandelstam in general, especially in the poem under consideration, since it is based on colloquial idioms and its rhythm and rhymes remind that of “folk” couplets; hence the poet uses first person plural point of view, that of collective “we”.

The idiomatic tone is set in the very first two lines in which Mandelstam coins idioms of his own: “not to feel the country” deconstructing two well-known idioms: “nog pod soboi ne chuyat’”: to be running very fast or to be flying, often to be beside oneself with joy (literally not to feel one’s feet), but also: to be run off one’s feet, to be extremely exhausted; however, Mandelstam creates a new meaning implying “running without looking back from fear” and “being deaf and dumb” since the Russian “chuyat’” also means “to hear” and “to feel”; hence the poet extends and develops it in the second line: “our speeches cannot be heard at ten paces; both meanings are rendered by the translators correctly, with the little exception that in Clarence Brown’s and W. S. Merwin’s translation active voice is changed into passive: Mandelstam: we do not feel (hear); Brown and Merwin: our lives don’t feel; in McDuff’s translation such words as “inaudible”, “conversation” destroy, in my view, rhythm and music from the start, making it a literal translation. The key image of the second “couplet” is that of Stalin’s of course: he was born and raised in Georgia, in the Caucasus; hence highlander, not “a mountaineer,” which may imply some kind of athletic competition. It is notable that at that time there were several other Georgian-born Communist party functionaries alive, for instance, Sergo Ordzhonikidze who would be killed in 1937, member of the so-called political bureau of the central committee and the minister of heavy industry; however, the reader would unmistakably identify unnamed “highlander” with Stalin.

Further, it is said that a poet-functionary Dem’yan Bednyi (real name Yefim Aleksandrovich Pridvorov, 1883-1945) who was friendly with Stalin and gave him books to read, once mentioned that Stalin returned books soiled with oily fingers, after which the poet fell out of favor, but was not persecuted further; a famous children’s poet Kornei Chukovsky wrote a long poem “Tarakanishche” [a giant cockroach] about the cockroach-dictator with giant moustache who was easily crushed in the end by a “brave sparrow,” not bigger animals. Everybody understood the implication, but it was Mandelstam who combined all the features adding Stalin’s habit of wearing a military uniform without shoulder straps (only during great holidays Stalin would put on field marshal’s, later generalissimo’s, uniform). One of Stalin’s long-term associates, Vasily Molotov (real name Skriabin), prime-minister in 1930-1941, and minister of foreign affairs in 1939-1949 and 1953-1956, who signed the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, had a very thin neck; hence “chicken-necked”, as Brown and Merwin rendered, is correct, while “thick-skinned”, as it appears in McDuff’s translation, is evidently not. Mandelstam further creates a Russian fairy-tale-like phantasmagoria turning half-men into demons, poltergeists and evil spirits. Again, Clarence Brown’s and W. S. Merwin’s translation is more exact both rhythmically and semantically than that of McDuff’s, which is like an exact interlinear translation, especially in his last but one couplet in which he destroys the music completely. The word “Ukaz” means in English “a decree” and goes back to the time of Ivan the Terrible, if not earlier. Etymologically, it derives from the verb “ukazyvat’,” which means “to show” or “to order.” It is notable that the manuscript as well as the authorized edition s of Collected Works of Mandelstam reads “grants a decree after a decree”, not “forges”. Perhaps it is linked to the Russian belief that a horseshoe brings happiness (in that meaning the word is used in Osip Mandelstam’s Pindaric Fragment “A Horseshoe Finder).

The real problem, however, is the last couplet in which Mandelstam coined a new idiom. The word “raspberry” in a thief jargon means “a criminal underworld,” usually that of thieves; it is a well–known fact now that Koba (Stalin’s past criminal and then Bolshevik party name) was robbing postal carriages, trains and even banks. “Old Bolsheviks” were uneasy about that, but since they needed money, Lenin convinced them that Stalin “expropriated” the rich giving money to the party (a Bolshevik Robin Hood of a kind). What seems even more important, however, is that the Russian idiom “ne zhisn’ a malina” [life like a raspberry] means “la dolce vita,” a sweet life. Mandelstam replaces “life” with “execution”, thus rhyming them since the Russian for “execution” [kazn’] and life [zhizn’] form a slant dissonance rhyme. In my view, it is impossible to render images, especially idioms literally into a foreign language; thus it is necessary to replace “raspberry”, which does not have the above implication in English. At first, I was considering just “a piece of cake” or even “a raspberry cake”, but then decided to move further and have chosen the English idiom “cakes and ale” and added a rhyme “jail,” which is justifiable, in my view, since Stalin has long been associated with the development of the prison and concentration camp system. In the end, Mandelstam consciously replaced “Georgian” with “Osette” because the Russian word “Ossetina” in comparison with “Gruzina” has an extra syllable necessary for preserving the meter, not just rhyme. It can be also justified since Stalin’s paternal grandfather Vissarion Dzhugashvili is said to be Ossetian. Although in my own translation I was not quite able to preserve anapest everywhere, I tried to preserve the rhyme and an alternation of longer and shorter lines.

Осип Эмильевич Мандельштам (1891 -1938)

Мы живем, под собою не чуя страны,

Наши речи за десять шагов не слышны,

А где хватит на полразговорца,

Там припомнят кремлевского горца.

Его толстые пальцы, как черви, жирны,

И слова, как пудовые гири, верны,

Тараканьи смеются глазища

И сияют его голенища.

А вокруг него сброд тонкошеих вождей,

Он играет услугами полулюдей.

Кто свистит, кто мяучит, кто хнычет,

Он один лишь бабачит и тычет.

Как подкову, дари’т за указом указ —

Кому в пах, кому в лоб, кому в бровь, кому в глаз.

Что ни казнь у него — то малина

И широкая грудь осетина.

Ноябрь 1933

Clarence Brown’s and W. S. Merwin’s Translation:

New York: Atheneum, 1974.

Our lives no longer feel ground under them

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But whenever there’s a snatch of talk

It turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

The ten thick worms his fingers,

His words like measures of weight,

The huge laughing cockroaches on top of his lip,

The glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

He toys with the tributes of half men.

One whistles, another meouws, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes,

One for the groin, one for the forehead, temple, eye .

He rolls the executions of his tongue like berries.

He wishes he could hug them like big friend back home.

David McDufff’s translation

Osip Mandelstam. Selected Poems. London: Writers and Readers, 1983.

We live without feeling the country beneath us,

our speech at ten paces inaudible,

and where there are enough for half a conversation

the name of the Kremlin mountaineer is dropped.

His thick fingers are fatty like worms,

but his words are as true as pound weights.

his cockroach whiskers laugh,

and the tops of his boots shine.

Around him a rabble of thick-skinned leaders,

he plays with the attentions of half-men.

Some whistle, some miaul, some shivel,

but he just bangs and pokes.

He forges his decrees like horseshoes —

some get it in the groin, some in the forehead.

some in the brows, some in the eyes.

Whatever the punishment he gives — raspberries,

And the broad chest of an Osette.

Translated by Ian Probstein

We live without feeling our country’s pulse,

We can’t hear ourselves, no one hears us,

If a word is uttered by chance,

Kremlin highlander is remembered at once.

Like worms his thick fingers are fat,

His words like pound weights are correct,

His cockroach moustache is full of laughter,

His army boots shine, he is sought after

By a mob of thin-necked leaders, half-men,

He uses their service, manipulating them:

Some are meowing or whistling, or whining,

He alone is poking, boking, and winning.

Like horseshoes, he grants his every decree

Poking some in the groin, in the brow, in the eye.

His executions are like cakes and ale,

His broad chest of Ossete eclipses the jail.

Editor’s note: some more translations of this poem

Dimitri Smirnov

We are living, but can’t feel the land where we stay,

More than ten steps away you can’t hear what we say.

But if people would talk on occasion,

They should mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

His thick fingers are bulky and fat like live-baits,

And his accurate words are as heavy as weights.

Cucaracha’s moustaches are screaming,

And his boot-tops are shining and gleaming.

But around him a crowd of thin-necked henchmen,

And he plays with the services of these half-men.

Some are whistling, some meowing, some sniffing,

He’s alone booming, poking and whiffing.

He is forging his rules and decrees like horseshoes –

Into groins, into foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Every killing for him is delight,

And Ossetian torso is wide.

Scott Horton

We live, not sensing our own country beneath us,

Ten steps away they dissolve, our speeches,

But where enough meet for half-conversation,

The Kremlin hillbilly is our preoccupation.

They’re like slimy worms, his fat fingers,

His words, as solid as weights of measure.

In his cockroach moustaches there’s a hint

Of laughter, while below his top boots gleam.

Round him a mob of thin-necked henchmen,

He pursues the enslavement of the half-men.

One whimpers, another warbles,

A third miaows, but he alone prods and probes.

He forges decree after decree, like horseshoes –

In groins, foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Wherever an execution’s happening though –

there’s raspberry, and the Ossetian’s giant torso

.

John Simkin

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches,

All we hear is the Kremlin mountaineer,

The murderer and peasant-slayer.

His fingers are fat as grubs

And the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips,

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boot tops gleam.

Around him a rabble of thin-necked leaders –

fawning half-men for him to play with.

The whinny, purr or whine

As he prates and points a finger,

One by one forging his laws, to be flung

Like horseshoes at the head, to the eye or the groin.

And every killing is a treat

For the broad-chested Ossete.

See also:

“On Translating a Poem by Osip Mandelstam” by José Manuel Prieto, tr. Esther Allen

http://www.bu.edu/translation/files/2011/01/Allen-Handout2.pdf

Ian Probstein’s translation of “Untruth”