If you’re a massless particle, you must always move at light speed. If you have mass, you must go slower. So why aren’t any neutrinos slow?

- When neutrinos were first theorized, they were introduced to have no charge and to carry energy and momentum away from certain nuclear decays.

- However, when we first started detecting them, they appeared to be completely massless, always moving indistinguishably from the speed of light.

- Yet more recent experiments have revealed that neutrinos oscillate, or change flavor, implying they must have mass. So if they have mass, where are all the slow ones?

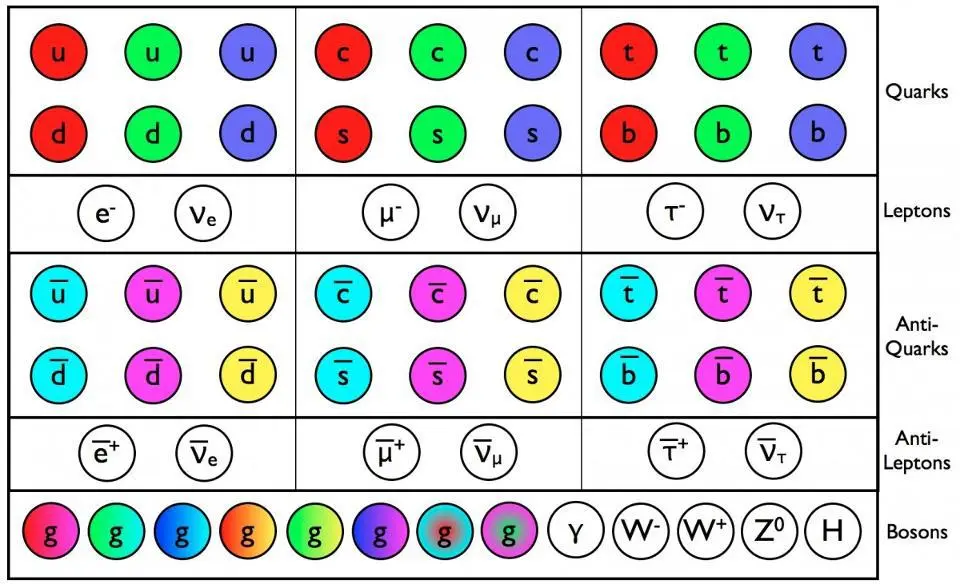

For many years, the neutrino was among the most puzzling and elusive of cosmic particles. It took more than two decades from when it was first predicted to when it was finally detected, and they came along with a bunch of surprises that make them unique among all the particles that we know of. They can “change flavor” from one type (electron, mu, tau) into another. All neutrinos always have a left-handed spin; all anti-neutrinos always have a right-handed spin. And every neutrino we’ve ever observed moves at speeds indistinguishable from the speed of light.

But must that be so? After all, if neutrinos can oscillate from one species into one another, that means they must have mass. If they have mass, then it’s forbidden for them to actually move at the speed of light; they must move slower. And after 13.8 billion years of cosmic evolution, surely some of the neutrinos that were produced long ago have slowed down to a reasonably accessible, non-relativistic speed. Yet, we’ve never seen one, causing us to wonder where are all the slow-moving neutrinos? As it turns out, they’re probably out there, just at levels well-below what current technology can detect.

The neutrino was first proposed in 1930, when a special type of decay — beta decay — seemed to violate two of the most important conservation laws of all: the conservation of energy and the conservation of momentum. When an atomic nucleus decayed in this fashion, it:

- increased in atomic number by 1,

- emitted an electron,

- and lost a little bit of rest mass.

When you added up the energy of the electron and the energy of the post-decay nucleus, including all the rest mass energy, it was always slightly less than the rest mass of the initial nucleus. In addition, when you measured the momentum of electron and the post-decay nucleus, it didn’t match the initial momentum of the pre-decay nucleus. Either energy and momentum were being lost, and these supposedly fundamental conservation laws were no good, or there was a hitherto undetected additional particle being created that carried that excess energy and momentum away.

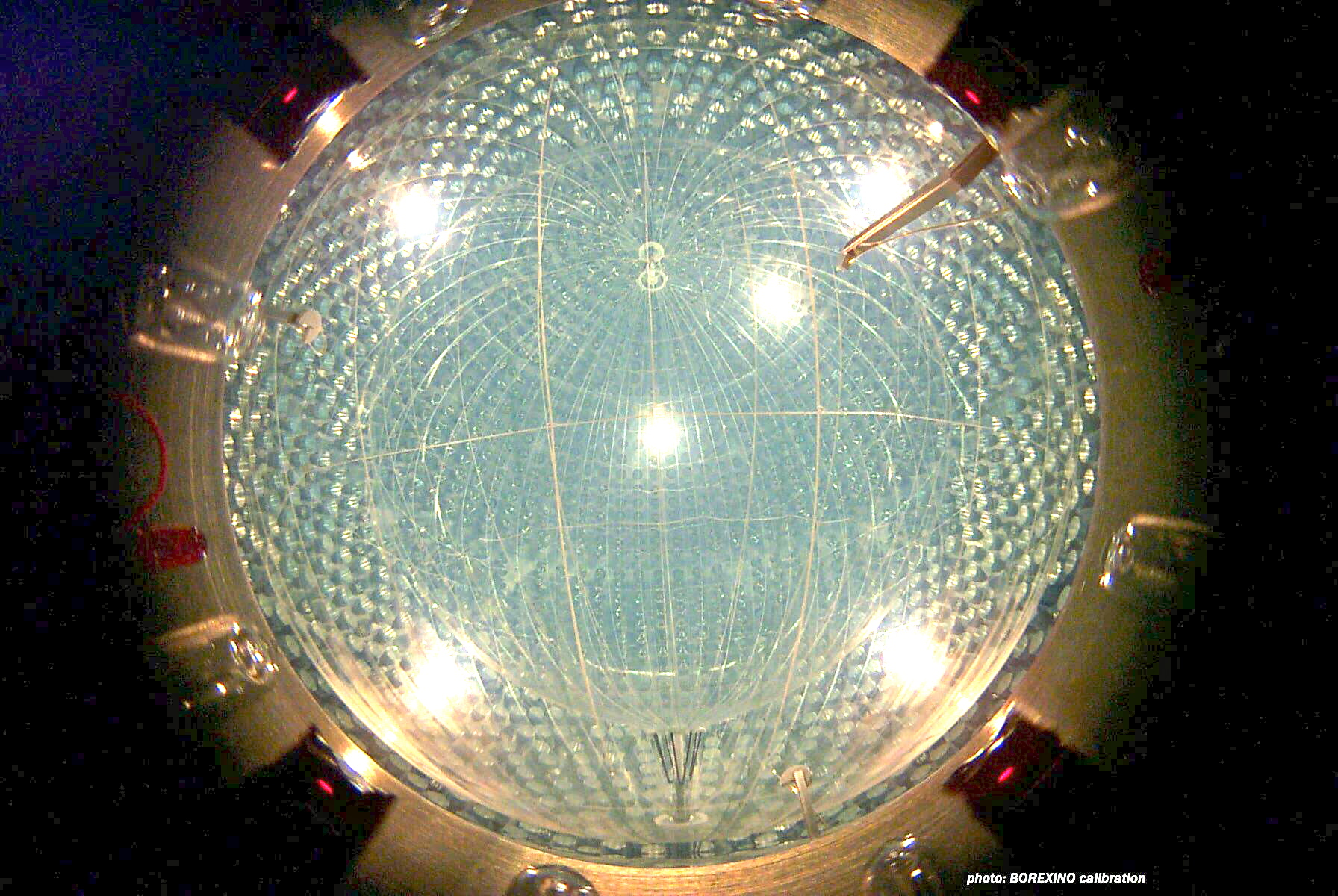

It would take approximately 26 years for that particle to be detected: the elusive neutrino. Although we couldn’t quite see these neutrinos directly — and still can’t — we can detect the particles they collide or react with, providing evidence of the neutrino’s existence and teaching us about its properties and interactions. There are a myriad of ways the neutrino has shown itself to us, and each one provides us with an independent measurement and constraint on its properties.

We’ve measured neutrinos and antineutrinos produced in nuclear reactors.

We’ve measured neutrinos produced by the Sun.

We’ve measured neutrinos and antineutrinos produced by cosmic rays that interact with our atmosphere.

We’ve measured neutrinos and antineutrinos produced by particle accelerator experiments.

We’ve measured neutrinos produced by the closest supernova to occur in the past century: SN 1987A.

And, in recent years, we’ve even measured a neutrino coming from the center of an active galaxy — a blazar — from under the ice in Antarctica.

With all of this information combined, we’ve learned an incredible amount of information about these ghostly neutrinos. Some particularly relevant facts are as follows:

- Every neutrino and antineutrino we’ve ever observed moves at speeds so fast they’re indistinguishable from the speed of light.

- Neutrinos and antineutrinos both come in three different flavors: electron, mu, and tau.

- Every neutrino we’ve ever observed is left-handed (if you point your thumb in its direction of motion, your left hand’s fingers “curl” in the direction of its spin, or intrinsic angular momentum), and every anti-neutrino is right-handed.

- Neutrinos and antineutrinos can oscillate, or change flavor, from one type into another when they pass through matter.

- And yet neutrinos and antineutrinos, despite appearing to move at the speed of light, must have a non-zero rest mass, otherwise this “neutrino oscillation” phenomenon would not be possible.

Neutrinos and antineutrinos come in a wide variety of energies, and the odds of having a neutrino interact with you increase with a neutrino’s energy. In other words, the more energy your neutrino has, the more likely it is to interact with you. For the majority of neutrinos produced in the modern Universe, through stars, supernovae, and other natural nuclear reactions, it would take about a light-year worth of lead to stop approximately half of the neutrinos fired upon it.

All of our observations, combined, have enabled us to draw some conclusions about the rest mass of neutrinos and antineutrinos. First off, they cannot be zero. The three types of neutrino almost certainly have different masses from one another, where the heaviest a neutrino is allowed to be is about 1/4,000,000th the mass of an electron, the next-lightest particle. And through two independent sets of measurements — from the large-scale structure of the Universe and the remnant light left over from the Big Bang — we can conclude that approximately one billion neutrinos and antineutrinos were produced in the Big Bang for every proton in the Universe today.

Here’s where the disconnect between theory and experiment lies. In theory, because neutrinos have a non-zero rest mass, it should be possible for them to slow down to non-relativistic speeds. In theory, the neutrinos left over from the Big Bang should have already slowed down to these speeds, where they’ll only be moving at a few hundred km/s today: slow enough that they should have fallen into galaxies and galaxy clusters by now, making up approximately ~1% of all the dark matter in the Universe.

But experimentally, we simply don’t have the capabilities to detect these slow-moving neutrinos directly. Their cross-section is literally millions of times too small to have a chance at seeing them, as these tiny energies wouldn’t produce recoils noticeable by our current equipment. Unless we could accelerate a modern neutrino detector to speeds extremely close to the speed of light, these low-energy neutrinos, the only ones that should exist at non-relativistic speeds, will remain undetectable.

And that’s unfortunate, because detecting these low-energy neutrinos — the ones that move slow compared to the speed of light — would enable us to perform an important test that we’ve never performed before. Imagine that you’ve got a neutrino, and you’re traveling behind it. If you look at this neutrino, you’ll measure it moving straight ahead: forward, in front of you. If you go to measure the neutrino’s angular momentum, it will behave as though it’s spinning counterclockwise: the same as if you pointed your left hand’s thumb forward and watched your fingers curl around it.

This is a fascinating paradox. It seems to indicate that you could transform a matter particle (a neutrino) into an antimatter particle (an antineutrino) simply by changing your motion relative to the neutrino. Alternatively, it’s possible that there really could be right-handed neutrinos and left-handed antineutrinos, and that we’ve just never seen them for some reason. It’s one of the biggest open questions about neutrinos, and the capability to detect low-energy neutrinos — the ones moving slow compared to the speed of light — would answer that question.

But we can’t really do that in practice. The lowest-energy neutrinos we’ve ever detected have so much energy that their speed must be, at minimum, 99.99999999995% the speed of light, which means that they can move no slower than 299,792,457.99985 meters-per-second. Even over cosmic distances, when we’ve observed neutrinos arriving from galaxies other than the Milky Way, we’ve detected absolutely no difference between a neutrino’s speed and the speed of light.

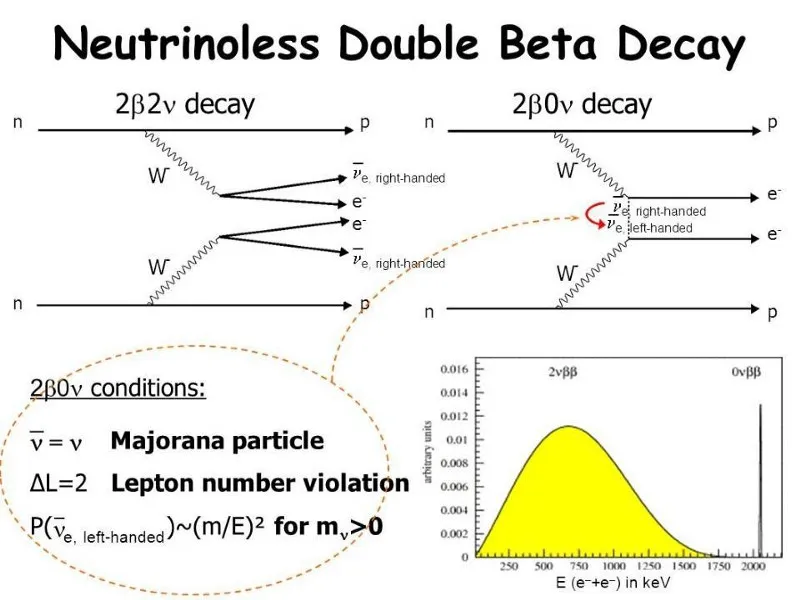

Nevertheless, there’s a tantalizing chance we have to resolve this paradox, despite the difficulty inherent to it. It’s possible to have an unstable atomic nucleus that doesn’t just undergo beta decay, but double beta decay: where two neutrons in the nucleus simultaneously both undergo beta decay. We’ve observed this process: where a nucleus changes its atomic number by 2, emits 2 electrons, and energy and momentum are both lost, corresponding to the emission of 2 (anti)neutrinos.

But if you could transform a neutrino into an antineutrino simply by changing your frame-of-reference, that would mean that neutrinos are a special, new type of particle that exists only in theory thus far: a Majorana fermion. It would mean that the antineutrino emitted by one neutron within a nucleus could, hypothetically, be absorbed (as a neutrino) by another neutron within the same nucleus, and you’d be able to get a decay where:

- the atomic number of the nucleus changed by 2,

- 2 electrons are emitted,

- but 0 neutrinos or antineutrinos are emitted.

There are currently multiple experiments, including the MAJORANA experiment, looking specifically for this neutrinoless double beta decay. If we observe it, it will fundamentally change our perspective on the elusive neutrino.

But for right now, with current technology, the only neutrinos (and antineutrinos) we can detect via their interactions move at speeds indistinguishable from the speed of light. Neutrinos might have mass, but their mass is so small that of all the ways the Universe has to create them, only the neutrinos made in the Big Bang itself should be moving slow compared to the speed of light today. Those neutrinos might be all around us, as an inevitable part of the galaxy, but we cannot directly detect them.

In theory, however, neutrinos can absolutely travel at any speed at all, so long as it’s slower than the cosmic speed limit: the speed of light in a vacuum. The issue we have is twofold:

- slow moving neutrinos have very low probabilities of interactions,

- and those interactions that do occur are so low in energy that we cannot presently detect them.

The only neutrino interactions we see are the ones coming from neutrinos moving indistinguishably close to the speed of light. Until there’s a revolutionary new technology or experimental technique, this will, however unfortunate it is, continue to be the case.