I always said God was against art and I still believe it. ~Elgar

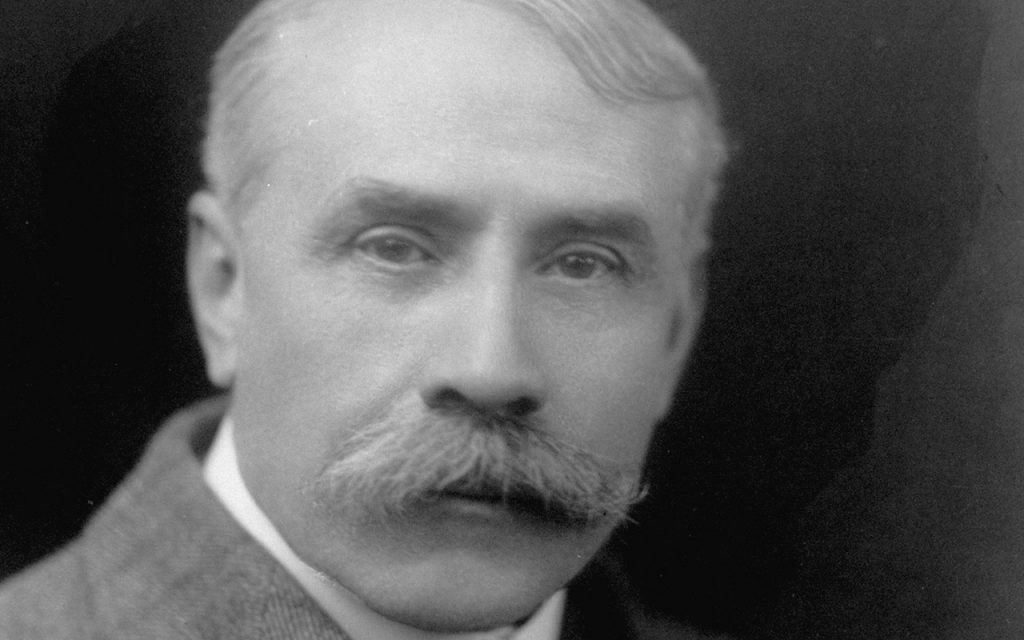

Edward Elgar wordt op 2 juni 1857 geboren in Broadheath, Engeland. Binnen zijn muzikale gezin leert hij als autodidact al snel viool, altviool en orgel spelen. Hij ontwikkelt zich tot concertmeester, arrangeur en dirigent en krijgt bekendheid dankzij een aantal salonstukken. Hij vervolgt met een aantal koorwerken en een zeer geslaagd oratorium, The Dream of Gerontius, op teksten van kardinaal John Henry Newman. Elgar staat bekend om zijn vurige temperament, iets wat je kan terughoren in zijn viool- en cellloconcert.

Je kent hem van…

Enigma Variaties, Celloconcert, Pomp and Circumstance Marches

Wist je dat…

- Hij gek was op woordspelingen, raadsels en puzzels? In zijn Enigma Variaties verstopte hij een geheime melodie waarvan men tot op de dag van vandaag probeert te ontcijferen wat het is.

- Hij zelf zei dat The Dream of Gerontius het beste is wat hij ooit heeft geschreven? https://www.nporadio4.nl/componisten/elgar-edward

Het meesterwerk Elgars Enigma

Enigma betekent raadsel. En ruim een eeuw na de première is het mysterie van de Enigma Variaties van de Engelse componist Edward Elgar nog altijd niet opgelost.

‘De Enigma Variaties belichamen de eenzaamheid van de kunstenaar’

Op een herfstige oktoberavond in 1898 stak componist Edward Elgar een sigaar op en ging achter de piano zitten. Het was een vermoeiende lesdag geweest en hij kon op de piano doel noch richting vinden. Dromerig improviseerde hij wat. Plotseling onderbrak zijn vrouw hem.

‘Edward’, zei ze, ‘dat is een mooi deuntje.’ Het was alsof de componist uit een droom ontwaakte, schreef hij later.

‘Deuntje?’ vroeg hij. ‘Welk deuntje?’

‘Wat je zonet speelde’, antwoordde ze. ‘Doe het nog eens. Ik vond het mooi.’

Elgar begon opnieuw totdat zijn vrouw plotseling riep: ‘Dit is het!’

En zo ontstond, volgens de componist, het thema van zijn beroemde Enigma Variaties. In een andere versie van het verhaal vroeg zijn vrouw wat hij aan het spelen was en antwoordde Elgar: ‘Niets, maar het zou wel iets kunnen worden.’ Enigma betekent raadsel en lange tijd weigerde de componist in te gaan op wat er achter die titel schuilging. Maar zo’n dertien jaar na de bejubelde première van het meesterwerk vertelde hij aan een muziekcriticus: ‘Toen ik het werk schreef weerspiegelde het mijn gevoel over de eenzaamheid waaraan iedere kunstenaar ten prooi valt. En voor mij belichaamt de muziek dat nog steeds.’

Mijn gedachte is dat muziek in de lucht hangt’, zei Elgar in een gesprek, twee jaar voordat hem het thema van de Enigma Variaties zou invallen. ‘Muziek is overal om ons heen, de wereld is er vol van en je neemt er simpelweg zoveel van als je nodig hebt.’ Misschien waren de noten die zich aan de componist openbaarden in zekere zin wel een enigma, een mysterie, voor hem. Het thema althans, want daarna boog hij zich met meesterschap over het uitwerken van tal van variaties. Of zoals een Britse musicoloog schreef: ‘De variaties beginnen misschien met “niets”, met een eenzame, melancholieke en aan zichzelf twijfelende kunstenaar, maar ze groeien uit tot iets heel anders: een beschrijving van een triomferende kunstenaar. In de finale getiteld ‘EDU’ – de koosnaam die zijn vrouw Alice aan Elgar gaf – horen we een man die iets van zichzelf gemaakt heeft.’

‘In de finale horen we een man die iets van zichzelf gemaakt heeft’

‘Mijn gedachte is dat muziek in de lucht hangt’, zei Elgar in een gesprek, twee jaar voordat hem het thema van de Enigma Variaties zou invallen. ‘Muziek is overal om ons heen, de wereld is er vol van en je neemt er simpelweg zoveel van als je nodig hebt.’ Misschien waren de noten die zich aan de componist openbaarden in zekere zin wel een enigma, een mysterie, voor hem. Het thema althans, want daarna boog hij zich met meesterschap over het uitwerken van tal van variaties. Of zoals een Britse musicoloog schreef: ‘De variaties beginnen misschien met “niets”, met een eenzame, melancholieke en aan zichzelf twijfelende kunstenaar, maar ze groeien uit tot iets heel anders: een beschrijving van een triomferende kunstenaar. In de finale getiteld ‘EDU’ – de koosnaam die zijn vrouw Alice aan Elgar gaf – horen we een man die iets van zichzelf gemaakt heeft.’

In Nimrod overwint Elgar de twijfels over zijn roeping als componist

De dertien andere variaties zijn muzikale portretten van Elgars dierbaren. De eerste, ‘CAE’, betreft zijn echtgenote Caroline Alice Elgar. En daarna passeert een lange rij vrienden, die hij met initialen of een koosnaam aanduidt. De muziek geeft een algemene schets van de karakters, maar vergroot soms ook een specifieke eigenschap uit, zoals het stotteren van Dora Penny, een vriendin van de Elgars, voor wie hij de tiende variatie ‘Dorabella’ schreef. Nerveuze lachjes, slaande deuren – allemaal muzikale grappen die Elgar in de muziek verwerkte. En hij bleef er ook op toezien dat het werk zijn naam eer aandeed, dat het een mysterie bleef. Dan gaat het bijvoorbeeld om de dertiende en voorlaatste variatie die de componist slechts aanduidde met drie sterren. Nog tot op de dag van vandaag gaan de speculaties door over de vraag welke persoon zich achter deze asteriksen verbergt. Elgar heeft het nooit willen onthullen. De beroemdste variatie werd de negende, Nimrod, genoemd naar de Bijbelse jager uit het Oude Testament, die de eerste machthebber op aarde werd. Het deel verwijst naar een ontmoeting met muziekuitgever en zielsverwant August Jaeger, die de aan zichzelf twijfelende Elgar ervan weerhield om met componeren te stoppen.

Een melodie die niet gespeeld wordt

Volgens het programmaboek bij de première in 1899 is het echte enigma van het stuk het feit dat er een groter thema is, een melodie die niet gespeeld wordt, maar waar de muziek wel naar verwijst. Ook dat geheim nam Elgar mee in zijn graf. Tal van musicologen hielden zich hiermee bezig. Er zijn vele theorieën. Volgens de één gaat het om een melodie uit de Praagse Symfonie van Mozart of een fragment uit Bachs Matthäus-Passion, anderen houden het op Rule Brittania waarbij Elgar het werk als geheel aan Engeland zou hebben opgedragen. Het blijven allemaal gissingen, een echte oplossing lijkt nog niet gevonden. De Enigma Variaties werden op die manier een werk dat de muziek oversteeg. https://www.classicstogo.nl/features/elgars-enigma/

Edward Elgar (1857-1934) The Dream of Gerontius, Op. 38 Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano (The Angel) Richard Lewis, tenor (Gerontius, Soul of Gerontius) Kim Borg, bass (The Priest, The Angel of Agony) The combined Hallé Choir and Sheffild Philharmonic Chorus (chorus master: Eric Chadwick) Ambrosian Singers (chorus master: John McCarthy) Hallé Orchestra, leader: Martin Milner Conducted by John Barbirolli 1965

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, OM, GCVO 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, concertos for violin and cello, and two symphonies. He also composed choral works, including The Dream of Gerontius, chamber music and songs. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924.

Although Elgar is often regarded as a typically English composer, most of his musical influences were not from England but from continental Europe. He felt himself to be an outsider, not only musically, but socially. In musical circles dominated by academics, he was a self-taught composer; in Protestant Britain, his Roman Catholicism was regarded with suspicion in some quarters; and in the class-conscious society of Victorian and Edwardian Britain, he was acutely sensitive about his humble origins even after he achieved recognition. He nevertheless married the daughter of a senior British Army officer. She inspired him both musically and socially, but he struggled to achieve success until his forties, when after a series of moderately successful works his Enigma Variations (1899) became immediately popular in Britain and overseas. He followed the Variations with a choral work, The Dream of Gerontius (1900), based on a Roman Catholic text that caused some disquiet in the Anglican establishment in Britain, but it became, and has remained, a core repertory work in Britain and elsewhere. His later full-length religious choral works were well received but have not entered the regular repertory.

In his fifties, Elgar composed a symphony and a violin concerto that were immensely successful. His second symphony and his cello concerto did not gain immediate public popularity and took many years to achieve a regular place in the concert repertory of British orchestras. Elgar’s music came, in his later years, to be seen as appealing chiefly to British audiences. His stock remained low for a generation after his death. It began to revive significantly in the 1960s, helped by new recordings of his works. Some of his works have, in recent years, been taken up again internationally, but the music continues to be played more in Britain than elsewhere.

Elgar has been described as the first composer to take the gramophone seriously. Between 1914 and 1925, he conducted a series of acoustic recordings of his works. The introduction of the moving-coil microphone in 1923 made far more accurate sound reproduction possible, and Elgar made new recordings of most of his major orchestral works and excerpts from The Dream of Gerontius.

Early years

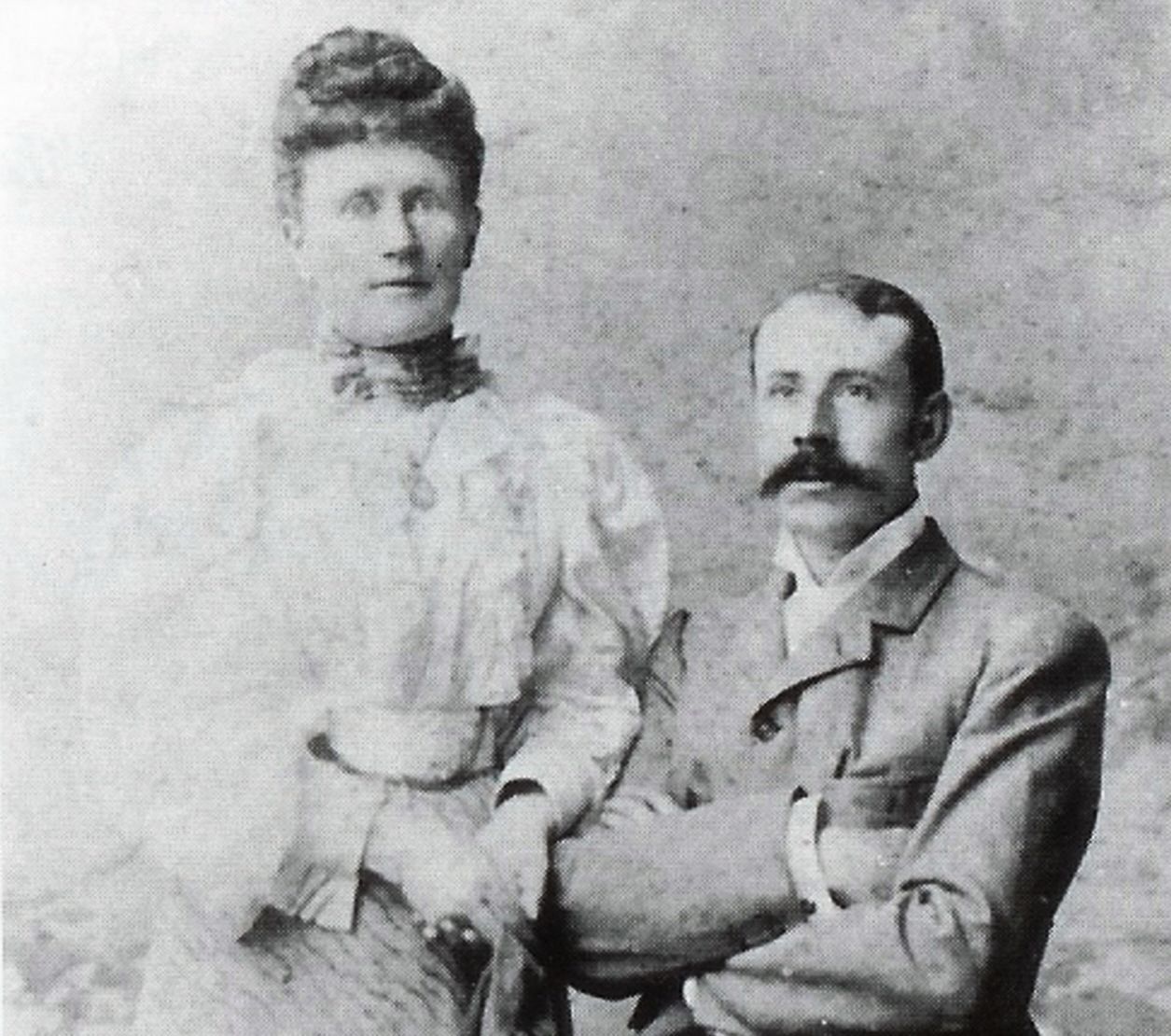

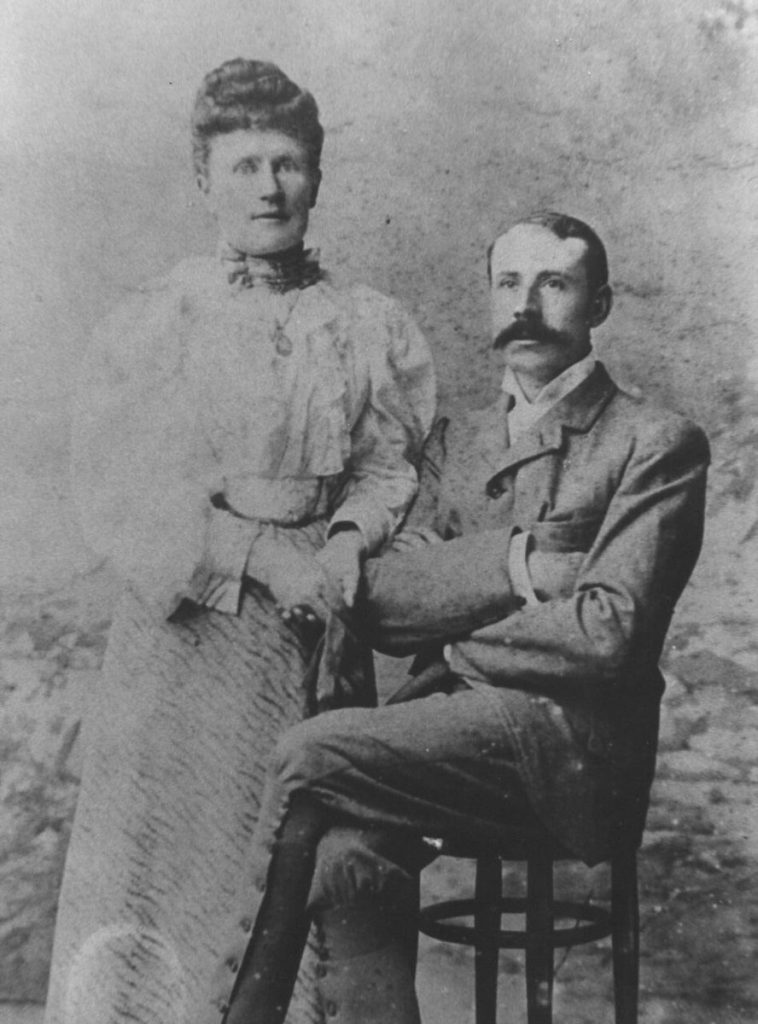

Edward Elgar was born in the small village of Lower Broadheath, outside Worcester, England. His father, William Henry Elgar (1821–1906), was raised in Dover and had been apprenticed to a London music publisher. In 1841 William moved to Worcester, where he worked as a piano tuner and set up a shop selling sheet music and musical instruments. In 1848 he married Ann Greening (1822–1902), daughter of a farm worker. Edward was the fourth of their seven children. Ann Elgar had converted to Roman Catholicism shortly before Edward’s birth, and he was baptised and brought up as a Roman Catholic, to the disapproval of his father. William Elgar was a violinist of professional standard and held the post of organist of St George’s Roman Catholic Church, Worcester, from 1846 to 1885. At his instigation, masses by Cherubini and Hummel were first heard at the Three Choirs Festival by the orchestra in which he played the violin. All the Elgar children received a musical upbringing. By the age of eight, Elgar was taking piano and violin lessons, and his father, who tuned the pianos at many grand houses in Worcestershire, would sometimes take him along, giving him the chance to display his skill to important local figures.[2]Elgar’s parents, William and Ann Elgar

Elgar’s mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical development. He inherited from her a discerning taste for literature and a passionate love of the countryside. His friend and biographer W. H. “Billy” Reed wrote that Elgar’s early surroundings had an influence that “permeated all his work and gave to his whole life that subtle but none the less true and sturdy English quality”. He began composing at an early age; for a play written and acted by the Elgar children when he was about ten, he wrote music that forty years later he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites titled The Wand of Youth.

Until he was fifteen, Elgar received a general education at Littleton (now Lyttleton) House school, near Worcester. However, his only formal musical training beyond piano and violin lessons from local teachers consisted of more advanced violin studies with Adolf Pollitzer, during brief visits to London in 1877–78. Elgar said, “my first music was learnt in the Cathedral … from books borrowed from the music library, when I was eight, nine or ten.” He worked through manuals of instruction on organ playing and read every book he could find on the theory of music. He later said that he had been most helped by Hubert Parry‘s articles in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Elgar began to learn German, in the hope of going to the Leipzig Conservatory for further musical studies, but his father could not afford to send him. Years later, a profile in The Musical Times considered that his failure to get to Leipzig was fortunate for Elgar’s musical development: “Thus the budding composer escaped the dogmatism of the schools.” However, it was a disappointment to Elgar that on leaving school in 1872 he went not to Leipzig but to the office of a local solicitor as a clerk. He did not find an office career congenial, and for fulfilment he turned not only to music but to literature, becoming a voracious reader. Around this time, he made his first public appearances as a violinist and organist.

After a few months, Elgar left the solicitor to embark on a musical career, giving piano and violin lessons and working occasionally in his father’s shop. He was an active member of the Worcester Glee club, along with his father, and he accompanied singers, played the violin, composed and arranged works, and conducted for the first time. Pollitzer believed that, as a violinist, Elgar had the potential to be one of the leading soloists in the country, but Elgar himself, having heard leading virtuosi at London concerts, felt his own violin playing lacked a full enough tone, and he abandoned his ambitions to be a soloist. At twenty-two he took up the post of conductor of the attendants’ band at the Worcester and County Lunatic Asylum in Powick, three miles (five km) from Worcester.The band consisted of: piccolo, flute, clarinet, two cornets, euphonium, three or four first and a similar number of second violins, occasional viola, cello, double bass and piano. Elgar coached the players and wrote and arranged their music, including quadrilles and polkas, for the unusual combination of instruments. The Musical Times wrote, “This practical experience proved to be of the greatest value to the young musician. … He acquired a practical knowledge of the capabilities of these different instruments. … He thereby got to know intimately the tone colour, the ins and outs of these and many other instruments.” He held the post for five years, from 1879, travelling to Powick once a week. Another post he held in his early days was professor of the violin at the Worcester College for the Blind Sons of Gentlemen.

Although rather solitary and introspective by nature, Elgar thrived in Worcester’s musical circles. He played in the violins at the Worcester and Birmingham Festivals, and one great experience was to play Dvořák‘s Symphony No. 6 and Stabat Mater under the composer’s baton. Elgar regularly played the bassoon in a wind quintet, alongside his brother Frank, an oboist (and conductor who ran his own wind band). Elgar arranged numerous pieces by Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, and others for the quintet, honing his arranging and compositional skills.[6]Schumann and Brahms, top, Rubinstein and Wagner, bottom, whose music inspired Elgar in Leipzig

In his first trips abroad, Elgar visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Saëns play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. In 1882 he wrote, “I got pretty well dosed with Schumann (my ideal!), Brahms, Rubinstein & Wagner, so had no cause to complain.” In Leipzig he visited a friend, Helen Weaver, who was a student at the Conservatoire. They became engaged in the summer of 1883, but for unknown reasons the engagement was broken off the next year. Elgar was greatly distressed, and some of his later cryptic dedications of romantic music may have alluded to Helen and his feelings for her. Throughout his life, Elgar was often inspired by close women friends; Helen Weaver was succeeded by Mary Lygon, Dora Penny, Julia Worthington, Alice Stuart Wortley and finally Vera Hockman, who enlivened his old age.

In 1882, seeking more professional orchestral experience, Elgar was employed to play violin in Birmingham with William Stockley’s Orchestra, for whom he would play every concert for the next seven years and where he later claimed he “learned all the music I know”. On 13 December 1883 he took part with Stockley in a performance at Birmingham Town Hall of one of his first works for full orchestra, the Sérénade mauresque – the first time one of his compositions had been performed by a professional orchestra. Stockley had invited him to conduct the piece but later recalled “he declined, and, further, insisted upon playing in his place in the orchestra. The consequence was that he had to appear, fiddle in hand, to acknowledge the genuine and hearty applause of the audience.” Elgar often went to London in an attempt to get his works published, but this period in his life found him frequently despondent and low on money. He wrote to a friend in April 1884, “My prospects are about as hopeless as ever … I am not wanting in energy I think, so sometimes I conclude that ’tis want of ability. … I have no money – not a cent.”

Marriage

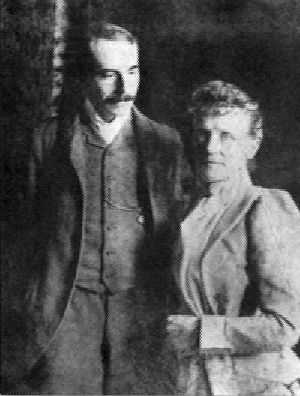

When Elgar was 29, he took on a new pupil, Caroline Alice Roberts, daughter of the late Major-General Sir Henry Roberts, and published author of verse and prose fiction. Eight years older than Elgar, Alice became his wife three years later. Elgar’s biographer Michael Kennedy writes, “Alice’s family was horrified by her intention to marry an unknown musician who worked in a shop and was a Roman Catholic. She was disinherited.”They were married on 8 May 1889, at Brompton Oratory. From then until her death, she acted as his business manager and social secretary, dealt with his mood swings, and was a perceptive musical critic. She did her best to gain him the attention of influential society, though with limited success. In time, he would learn to accept the honours given him, realising that they mattered more to her and her social class and recognising what she had given up to further his career. In her diary, she wrote, “The care of a genius is enough of a life work for any woman.” As an engagement present, Elgar dedicated his short violin-and-piano piece Salut d’Amour to her. With Alice’s encouragement, the Elgars moved to London to be closer to the centre of British musical life, and Elgar started devoting his time to composition. Their only child, Carice Irene, was born at their home in West Kensington on 14 August 1890. Her name, revealed in Elgar’s dedication of Salut d’Amour, was a contraction of her mother’s names Caroline and Alice.

Elgar took full advantage of the opportunity to hear unfamiliar music. In the days before miniature scores and recordings were available, it was not easy for young composers to get to know new music. Elgar took every chance to do so at the Crystal Palace concerts. He and Alice attended day after day, hearing music by a wide range of composers. Among these were masters of orchestration from whom he learned much, such as Berlioz and Richard Wagner. His own compositions, however, made little impact on London’s musical scene. August Manns conducted Elgar’s orchestral version of Salut d’amour and the Suite in D at the Crystal Palace, and two publishers accepted some of Elgar’s violin pieces, organ voluntaries, and part songs. Some tantalising opportunities seemed to be within reach but vanished unexpectedly. For example, an offer from the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, to run through some of his works was withdrawn at the last second when Sir Arthur Sullivan arrived unannounced to rehearse some of his own music. Sullivan was horrified when Elgar later told him what had happened. Elgar’s only important commission while in London came from his home city: the Worcester Festival Committee invited him to compose a short orchestral work for the 1890 Three Choirs Festival. The result is described by Diana McVeagh in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, as “his first major work, the assured and uninhibited Froissart.” Elgar conducted the first performance in Worcester in September 1890. For lack of other work, he was obliged to leave London in 1891 and return with his wife and child to Worcestershire, where he could earn a living conducting local musical ensembles and teaching. They settled in Alice’s former home town, Great Malvern. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Elgar