“Before the passing sky, in long hours of contemplation of its magnificent and ever-changing beauty, I am seized by an incomparable emotion. The whole expanse of nature is reflected in my own sincere and feeble soul.” Claude Debussy

“To feel the supreme and moving beauty of the spectacle to which Nature invites her ephemeral guests! … that is what I call prayer.” Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy, the great French composer who died 100 years ago in Paris, is that rare thing: a great innovator whom the whole world loves. His well-known piano pieces, such as Clair de Lune and Girl with the Flaxen Hair, are among the great “lollipops” of all time, while many have said that his wonderful orchestral Prelude l’apres-midi d’un faune, announces the beginning of modern music. He is the master painter of music, which means that even his most ambitious pieces enter the mind and heart with amazing ease. And yet they are also milestones in the development of the modernist pantheon, worthy to stand alongside similarly radical works by Stravinsky and Boulez.

Recovering the sense of Debussy as a radical is no easy task, given the fact that his pictorialisms are now so familiar, and have been imitated by film composers a thousand times over. Added to which, his choice of what to picture might seem a touch escapist – he loved everything faraway and strange; the play of wind on the waves, the feeling of a deserted temple under the moonlight, revellers in a Spanish village fiesta.

An even more severe charge is that Debussy’s music lacks real substance, compared with, say, a Bach fugue or a Beethoven sonata. A critic of the Boston premiere of La Mer in 1907 sarcastically dubbed the piece “Mal de Mer” (seasickness). Some modern composers have a ready retort to the hostile critic. They can say: “Of course my music has substance! I have invented a brand new grammar of music, and if you can’t hear it, that’s your problem.” But Debussy never makes that defence, which is a large part of his appeal. He is utterly honest, refusing to hide behind complicated technical procedures. His aim was to “penetrate to the naked flesh of emotion”, so he had to be naked as a composer, avoiding routine and trusting only in his instinct.

What this led to is a musical language focused on the fragmentary gesture – a sequence of two chords, a tendril-like scrap of melody, an orchestral shimmer. The encounter between these things generates another gesture and then another, like those time-lapse films of plants throwing out tendrils. What guided Debussy from one gesture and chord to another was an absolutely infallible instinct for the exact weight and flavour of a harmony, and what the next one should be to balance or offset it. As he famously put it: “ma seule regle, c’est mon plaisir” – my only rule is what pleases me.

Put thus, it might seem as if Debussy simply turned self-indulgence into a principle. His private life would suggest as much. He was desperately poor for most of his life, but that didn’t stop him from spending what he had on knick-knacks, while his conduct towards the women in his life was shamelessly duplicitous.

Debussy’s earliest compositions are not so far from the music that surrounded him in 1880s Paris. The turning point was the premiere of Pelleas and Melisande in 1902, which replaced the passionate avowals and gorgeous ballets and orchestral noise of the typical French opera with something absolutely unprecedented – a drama told in murmurs and half-hints and silences.

After that, came a succession of masterpieces, each of which seemed to refine Debussy’s language of fragmentary gestures – until the very end when, during his final illness, and with France suffering grievously in the First World War, Debussy broke through to a new, more austere “neoclassical” style that harked back to the 18th-century French music that he loved.

Whether violent or dreamy, the miracle of Debussy’s astonishing body of work is that the thing that prompted each piece, whether it’s a lacquered Japanese picture of goldfish, or a description of a ruined temple, always vanishes into pure music. Like all great music, by Bach or Beethoven or Brahms, Debussy’s takes its cue from the real world, then leaves it behind.

As the great modernist and Debussy disciple Pierre Boulez once said, Debussy in his greatest works found a way of creating musical form that is “instantaneous”, renewing itself from one moment to the next. That is still the dream of modern music, which is why Claude Debussy still seems like our contemporary.

To praise him as the first musical modernist, true though that is, seems too limiting. In his evanescent harmonies and melodic arabesques we are put directly in touch with something much grander: the mysteriousness that is the kernel of all art.

The Daily Telegraph, London https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/music/claude-debussy-french-composer-of-claire-de-lune-died-100-years-ago-in-paris-20180321-h0xqxr.html

Hoewel Claude van eenvoudige komaf was en er binnen het gezin Debussy weinig aan muziek werd gedaan, werd zijn talent al vroeg ontdekt. Dankzij bemiddeling van madame Mauté, de schoonmoeder van de dichter Paul Verlaine, mocht hij in 1873 naar het Conservatoire de Paris, waar hij pianoles kreeg van Antoine François Marmontel en harmonieleer van Émile Durand. Ook volgde hij korte tijd lessen bij César Franck.

In 1879 vroeg de weldoenster van Tsjaikovski, gravin Nadezjda Filaretovna von Meck, aan Marmontel of hij een geschikte jonge pianist wist voor haar huistrio. Hij maakte haar attent op Debussy. Zijn spel viel zodanig in de smaak dat hij in 1882 met de familie von Meck naar Rusland ging.

Na terugkeer volgde hij compositielessen bij Ernest Guiraud, die hem adviseerde eenvoudiger te schrijven, wilde hij in aanmerking komen voor de Prix de Rome.

Parijs-Rome-Parijs

In 1884 lukte hem dit met zijn cantate L’enfant prodigue, hoewel de componist Charles Gounod, die hem als genie beschouwde, voor hem in de bres moest springen. De toekenning van de prijs stelde Debussy in staat twee jaar in Rome te werken en te studeren. Dit overigens niet naar eigen genoegen, want het verblijf aldaar werd door hem als een kwelling ervaren. Hij zei niet tegen het klimaat te kunnen, zich niet te interesseren voor de antieke kunst en zich regelrecht te ergeren aan de feesten die hij moest bijwonen. Hier schreef hij het orkeststuk Printemps, dat door de jury in Parijs werd weggehoond. De secretaris van de Académie schreef in zijn rapport dat het zeer wenselijk zou zijn als Debussy zich niet verloor in dit soort impressionisme, dat hij als een van de gevaarlijkste vijanden van kunstwerken beschouwde. Debussy was inmiddels bezig aan een derde werk, getiteld La Demoiselle élue, op een vertaalde tekst van Dante Gabriel Rossetti, maar voor hij het voltooid had was hij al uit Rome vertrokken, nog voor de twee jaren voorbij waren. De jury weigerde Printemps uit te laten voeren, waarop Debussy zich verzette tegen een uitvoering van La Demoiselle élue. Hiermee was de breuk tussen hem en de leiders van de Académie volkomen.

Gedurende een bezoek aan Bayreuth (1888-89) kwam Debussy in contact met de muziek van Richard Wagner, die een dwingende greep op zijn werk leek te krijgen. Tijdens de Wereldtentoonstelling van 1889 in Parijs raakte hij echter onder de bekoring van Spaanse en vooral ook Javaanse muziek, met name van de klanken van de gamelan. Hierdoor lukte het hem onder de invloed van Wagner uit te komen en een hoogst oorspronkelijke, eigen klanktaal te ontwikkelen.

Huwelijken

In 1899 huwde Debussy Rosalie Texier, een meisje van eenvoudige komaf, dat hem voorbeeldig terzijde stond in de moeilijke tijd voordat hij bekendheid begon te genieten. In 1904 wenste Debussy echter van haar te scheiden om te kunnen trouwen met hun gezamenlijke vriendin Emma Bardac-Moyse. Door dit tweede huwelijk kwam hij in aanraking met de “betere kringen”, hoewel dit niet betekende dat er een einde kwam aan zijn financiële zorgen. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born to a family of modest means and little cultural involvement, Debussy showed enough musical talent to be admitted at the age of ten to France’s leading music college, the Conservatoire de Paris. He originally studied the piano, but found his vocation in innovative composition, despite the disapproval of the Conservatoire’s conservative professors. He took many years to develop his mature style, and was nearly 40 when he achieved international fame in 1902 with the only opera he completed, Pelléas et Mélisande.

Debussy’s orchestral works include Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894), Nocturnes (1897–1899) and Images (1905–1912). His music was to a considerable extent a reaction against Wagner and the German musical tradition. He regarded the classical symphony as obsolete and sought an alternative in his “symphonic sketches”, La mer (1903–1905). His piano works include two books of Préludes and one of Études. Throughout his career he wrote mélodies based on a wide variety of poetry, including his own. He was greatly influenced by the Symbolist poetic movement of the later 19th century. A small number of works, including the early La Damoiselle élue and the late Le Martyre de saint Sébastien have important parts for chorus. In his final years, he focused on chamber music, completing three of six planned sonatas for different combinations of instruments.

With early influences including Russian and Far Eastern music, Debussy developed his own style of harmony and orchestral colouring, derided – and unsuccessfully resisted – by much of the musical establishment of the day. His works have strongly influenced a wide range of composers including Béla Bartók, Olivier Messiaen, George Benjamin, and the jazz pianist and composer Bill Evans. Debussy died from cancer at his home in Paris at the age of 55 after a composing career of a little more than 30 years.

Debussy and Impressionism

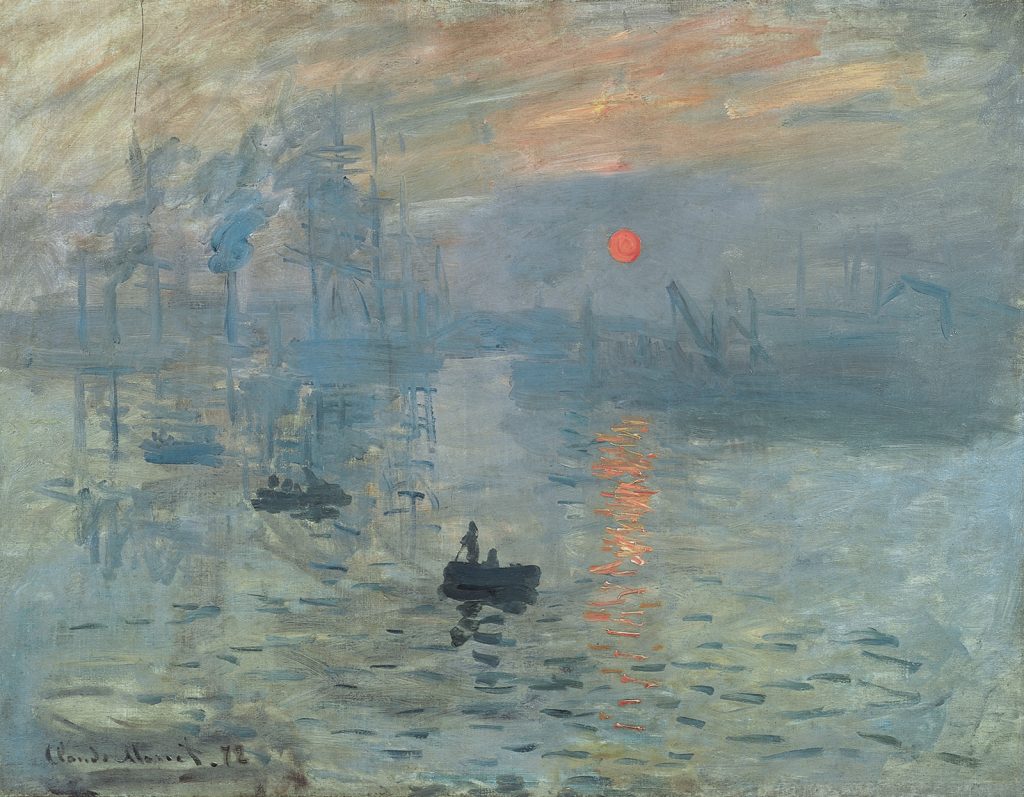

Monet‘s Impression, soleil levant (1872), from which “Impressionism” takes its name

The application of the term “Impressionist” to Debussy and the music he influenced has been much debated, both during his lifetime and since. The analyst Richard Langham Smith writes that Impressionism was originally a term coined to describe a style of late 19th-century French painting, typically scenes suffused with reflected light in which the emphasis is on the overall impression rather than outline or clarity of detail, as in works by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and others.[109] Langham Smith writes that the term became transferred to the compositions of Debussy and others which were “concerned with the representation of landscape or natural phenomena, particularly the water and light imagery dear to Impressionists, through subtle textures suffused with instrumental colour”.

Among painters, Debussy particularly admired Turner, but also drew inspiration from Whistler. With the latter in mind the composer wrote to the violinist Eugène Ysaÿe in 1894 describing the orchestral Nocturnes as “an experiment in the different combinations that can be obtained from one colour – what a study in grey would be in painting.”

Debussy strongly objected to the use of the word “Impressionism” for his (or anybody else’s) music, but it has continually been attached to him since the assessors at the Conservatoire first applied it, opprobriously, to his early work Printemps. Langham Smith comments that Debussy wrote many piano pieces with titles evocative of nature – “Reflets dans l’eau” (1905), “Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir” (1910) and “Brouillards” (1913) – and suggests that the Impressionist painters’ use of brush-strokes and dots is paralleled in the music of Debussy. Although Debussy said that anyone using the term (whether about painting or music) was an imbecile, some Debussy scholars have taken a less absolutist line. Lockspeiser calls La mer “the greatest example of an orchestral Impressionist work”,[114] and more recently in The Cambridge Companion to Debussy Nigel Simeone comments, “It does not seem unduly far-fetched to see a parallel in Monet’s seascapes”.

In this context may be placed Debussy’s pantheistic eulogy to Nature, in a 1911 interview with Henry Malherbe:

I have made mysterious Nature my religion … When I gaze at a sunset sky and spend hours contemplating its marvellous ever-changing beauty, an extraordinary emotion overwhelms me. Nature in all its vastness is truthfully reflected in my sincere though feeble soul. Around me are the trees stretching up their branches to the skies, the perfumed flowers gladdening the meadow, the gentle grass-carpeted earth, … and my hands unconsciously assume an attitude of adoration.

In contrast to the “impressionistic” characterisation of Debussy’s music, several writers have suggested that he structured at least some of his music on rigorous mathematical lines. In 1983 the pianist and scholar Roy Howat published a book contending that certain of Debussy’s works are proportioned using mathematical models, even while using an apparent classical structure such as sonata form. Howat suggests that some of Debussy’s pieces can be divided into sections that reflect the golden ratio, which is approximated by ratios of consecutive numbers in the Fibonacci sequence. Simon Trezise, in his 1994 book Debussy: La Mer, finds the intrinsic evidence “remarkable,” with the caveat that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy deliberately sought such proportions. Lesure takes a similar view, endorsing Howat’s conclusions while not taking a view on Debussy’s conscious intentions.

Musical idiom

Debussy wrote “We must agree that the beauty of a work of art will always remain a mystery […] we can never be absolutely sure ‘how it’s made.’ We must at all costs preserve this magic which is peculiar to music and to which music, by its nature, is of all the arts the most receptive.”

Nevertheless, there are many indicators of the sources and elements of Debussy’s idiom. Writing in 1958, the critic Rudolph Reti summarised six features of Debussy’s music, which he asserted “established a new concept of tonality in European music”: the frequent use of lengthy pedal points – “not merely bass pedals in the actual sense of the term, but sustained ‘pedals’ in any voice”; glittering passages and webs of figurations which distract from occasional absence of tonality; frequent use of parallel chords which are “in essence not harmonies at all, but rather ‘chordal melodies’, enriched unisons”, described by some writers as non-functional harmonies; bitonality, or at least bitonal chords; use of the whole-tone and pentatonic scales; and unprepared modulations, “without any harmonic bridge”. Reti concludes that Debussy’s achievement was the synthesis of monophonic based “melodic tonality” with harmonies, albeit different from those of “harmonic tonality”.

In 1889, Debussy held conversations with his former teacher Guiraud, which included exploration of harmonic possibilities at the piano. The discussion, and Debussy’s chordal keyboard improvisations, were noted by a younger pupil of Guiraud, Maurice Emmanuel. The chord sequences played by Debussy include some of the elements identified by Reti. They may also indicate the influence on Debussy of Satie‘s 1887 Trois Sarabandes. A further improvisation by Debussy during this conversation included a sequence of whole tone harmonies which may have been inspired by the music of Glinka or Rimsky-Korsakov which was becoming known in Paris at this time. During the conversation, Debussy told Guiraud, “There is no theory. You have only to listen. Pleasure is the law!” – although he also conceded, “I feel free because I have been through the mill, and I don’t write in the fugal style because I know it.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Debussy

Yampolsky Vladimir Oistrakh David

Founding Concert of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra Recorded live at the Lucerne Festival, Summer 2003 Concert Hall of the Culture- and Convention Center Lucerne, 14. August 2003 Rachel Harnisch – soprano Eteri Gvazava – soprano Schweizer Kammerchor / Chorus Master – Fritz Näf Lucerne Festival Orchestra Claudio Abbado – conductor Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien Musique de scène sur le mystère en cinq actes de Gabriele D’Annunzio The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian Incidental music to the msytery play in five acts by Gabriele d’Annunzio Das Martyrium des heiligen Sebastian Bühnenmusik zum Mysterienspiel in fünf Akten von Gabriele D’Annunzio 2:05 I. La Cour des Lys (11:49) The Court of Lilies Der Lilienhof 13:58 II. La Chambre magique (9:20) The Magic Chamber Der magische Raum 23:10 III. Le Concile des faux dieux (6:08) The Council of the False Gods Der Rat der falschen Götter 29:28 IV. Le Laurier bléssé (4:55) The Wounded Laurel Der verletzte Lorbeerbaum 34:21 V. Le Paradis (4:55) Paradise Das Paradies The programme of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra’s inaugural concert comprised works by Claude Debussy, with the focal point being the 1911 stage music to Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, based on stations from the life of Saint Sebastian, who was killed by archers because of his faith. This mystery play, with its elements of music, song, recitation, dance and sets, follows the idea of the total artwork. From Debussy’s musical inserts for this five-hour staged work, Abbado put together a five-part suite comprising preludes, dances, soloistic sections and choruses. The speaking roles are completely dispensed with, and the orchestra, chorus and soloists are the protagonists of an expressive sound-picutre comprising some of the most mature and beautiful music Debussy ever wrote. Claudio Abbado and the Lucerne Festival have enjoyed a close musical relationship spanning nearly four decades. Like many now world-famous conductors, Abbado, too, made his début in Lucerne at the rostrum of the Swiss Festival Orchestra, which from 1943 to 1993 made a decisive mark on the summer music festival. lt was in 1966 that he first conducted the ensemble, made up of Switzerland’s best musicians. This was the time when the young conductor also presented himself to the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras. Since then Abbado has been a regular guest on the shore of Lake Lucerne. He came with the Vienna Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra and the Philharmonia Orchestra, and was the first person to bring the music of Luigi Nono to Lucerne, the piece in question being II canto sospeso, which he performed in 1979 with the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala Milano. In 1989 Abbado was elected Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, and with this orchestra, which had been associated with the festival for decades, he now came to Lucerne every year from the end of August to the beginning of September. Exactly five years ago Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic had the honour of performing the opening concert in the new concert hall of the Lucerne Culture und Conference Centre, designed by Jean Nouvel and Russell Johnson. Abbado did not, however, just come to Lucerne as the chief conductor of several major European orchestras. Ha has always been committed to promoting young talent, und has founded several youth orchestras, which he has introduced at the Lucerne Festival. He performed there in 1980 and 1985 with the European Community Youth Orchestra, in 1986 and 1988 with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and in 1996 with the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra. The new Lucerne Festival Orchestra is an internationally unique orchestra formed for summer 2003, which right at the start of the festival ensured great musical moments and global headlines: “A conductor is back, an orchestra reborn”, wrote The New York Times; “The marvel in Lucerne”, acclaimed Berlin’s Tagesspiegel. With this newly formed orchestra Abbado was continuing the long tradition of a resident festival orchestra, begun by Arturo Toscanini at the first Lucerne Summer Festival with a “Concert de Gala” when he conducted in front of Wagner’s former residence in Tribschen in 1938. lt has been in the new Lucerne Festival Orchestra that famous musicians have met and, exclusively in this grouping, given performances of works from the symphonic repertoire. The orchestra’s principal desks have been occupied by soloists such as Kolja Blacher, Renaud und Gautier Capucon, Wolfram Christ, Stephan Dohr, Georg Faust, Natalia Gutman, Albrecht Mayer, Emmanuel Pahud, Diemut Poppen and Alois Posch, as well as by members of the Hagen Quartet and the Ensemble Sabine Meyer. The basis has been provided by the Mahler Chamber Orchestra – around 50 musicians with whom Abbado has collaborated for years.

“To create – to be creative – is to draw a door on the wall, and then open the door. ‘Clair de lune’ opens this door wide to transport us to a time where time doesn’t pass. That’s why we become children again when we listen to this music. Artists exploring ideas together become like childhood friends. Alexandre simply closed his eyes and we found each other, on the other side of the door.” Yoann Bourgeois