Early life

Born at Podolskaya Street in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich’s paternal grandfather, originally surnamed Szostakowicz, was of Polish Roman Catholic descent (his family roots trace to the region of the town of Vileyka in today’s Belarus), but his immediate forebears came from Siberia. A Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–4, Bolesław Szostakowicz was exiled to Narym (near Tomsk) in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitri Karakozov‘s assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II. When his term of exile ended, Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer’s father, was born in exile in Narim in 1875 and studied physics and mathematics at Saint Petersburg University, graduating in 1899. He then went to work as an engineer under Dmitri Mendeleev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903 he married another Siberian transplant to the capital, Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, one of six children born to a Russian Siberian native.

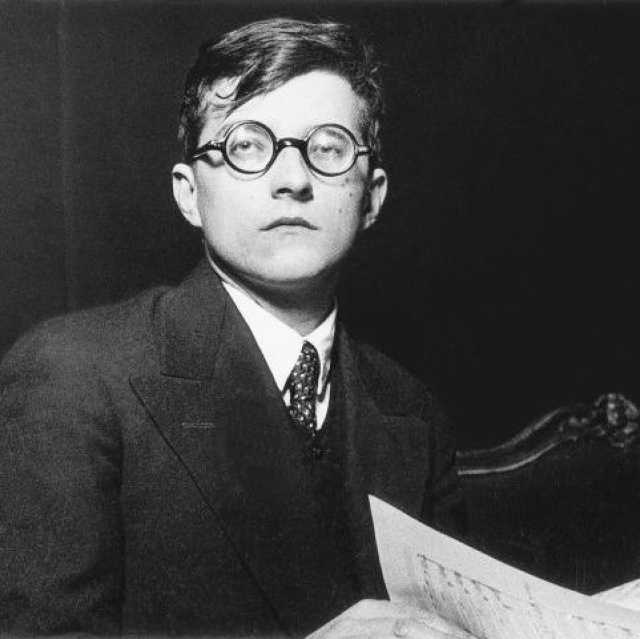

Their son, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, displayed significant musical talent after he began piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. On several occasions he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get “caught in the act” of playing the previous lesson’s music while pretending to read different music placed in front of him. In 1918 he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party murdered by Bolshevik sailors.

In 1919, at age 13, Shostakovich was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov, who monitored his progress closely and promoted him. Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev after a year in the class of Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, with whom he became friends. He also attended Alexander Ossovsky‘s music history classes. Steinberg tried to guide Shostakovich on the path of the great Russian composers, but was disappointed to see him ‘wasting’ his talent and imitating Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev. Shostakovich also suffered for his perceived lack of political zeal, and initially failed his exam in Marxist methodology in 1926. His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered 1926), written as his graduation piece at the age of 19. This work brought him to the attention of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who helped Shostakovich find accommodation and work in Moscow, and sent a driver around in “a very stylish automobile” to take him to a concert.

Early career

After graduation, Shostakovich initially embarked on a dual career as concert pianist and composer, but his dry playing style was often unappreciated (his American biographer, Laurel Fay, comments on his “emotional restraint” and “riveting rhythmic drive”). He won an “honorable mention” at the First International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927 and attributed the disappointing result to suffering from appendicitis and the jury being all Polish. He had his appendix removed in April 1927. After the competition Shostakovich met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by the composer’s First Symphony that he conducted it at its Berlin premiere later that year. Leopold Stokowski was equally impressed and gave the work its U.S. premiere the following year in Philadelphia. Stokowski also made the work’s first recording.

Shostakovich concentrated on composition thereafter and soon limited his performances primarily to his own works. In 1927 he wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a pro-Soviet choral finale. Owing to its experimental nature, as with the subsequent Third Symphony, it was not critically acclaimed with the enthusiasm given to the First.

1927 also marked the beginning of Shostakovich’s relationship with Ivan Sollertinsky, who remained his closest friend until the latter’s death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced the composer to Mahler’s music, which had a strong influence on Shostakovich from the Fourth Symphony onward.

While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Nikolai Gogol. In June 1929, against the composer’s wishes, the opera was given a concert performance; it was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM). Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension among musicians.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which was first performed in 1934. It was immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as “the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party”, and as an opera that “could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture”.[17]

Shostakovich married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Difficulties led to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first child, Galina.

First denunciation

On 17 January 1936, Joseph Stalin paid a rare visit to the opera for a performance of a new work, Quiet Flows the Don, based on the novel by Mikhail Sholokhov, by the little-known composer Ivan Dzerzhinsky, who was called to Stalin’s box at the end of the performance and told that his work had “considerable ideological-political value”. On 26 January, Stalin revisited the opera, accompanied by Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov and Anastas Mikoyan, to hear Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He and his entourage left without speaking to anyone. Shostakovich had been forewarned by a friend that he should postpone a planned concert tour in Arkhangelsk in order to be present at that particular performance. Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was “white as a sheet” when he went to take his bow after the third act. In letters to Sollertinsky, Shostakovich recounted the horror with which he watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions laughed at the lovemaking scene between Sergei and Katerina. The next day, Shostakovich left for Arkhangelsk, and was there when he heard on 28 January that Pravda had published a tirade titled Muddle Instead of Music, complaining that the opera was a “deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds…[that] quacks, hoots, pants and gasps.”[22] This was the signal for a nationwide campaign, during which even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they “failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda“.[23] There was resistance from those who admired Shostakovich, including Sollertinsky, who turned up at a composers’ meeting in Leningrad called to denounce the opera and praised it instead. Two other speakers supported him. When Shostakovich returned to Leningrad, he had a telephone call from the commander of the Leningrad Military District, who had been asked by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky to make sure that he was all right. When the writer Isaac Babel was under arrest four years later, he told his interrogators that “it was common ground for us to proclaim the genius of the slighted Shostakovich.”

On 6 February, Shostakovich was again attacked in Pravda, this time for his light comic ballet The Limpid Stream, which was denounced because “it jangles and expresses nothing” and did not give an accurate picture of peasant life on a collective farm. Fearful that he was about to be arrested, Shostakovich secured an appointment with the Chairman of the USSR State Committee on Culture, Platon Kerzhentsev, who reported to Stalin and Molotov that he had instructed the composer to “reject formalist errors and in his art attain something that could be understood by the broad masses”, and that Shostakovich had admitted being in the wrong and had asked for a meeting with Stalin, which was not granted.

As a result of this campaign, commissions began to fall off, and Shostakovich’s income fell by about three-quarters. His Fourth Symphony was due to receive its premiere on 11 December 1936, but he withdrew it from the public, possibly because it was banned, and the symphony was not performed until 1961. Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was also suppressed. A bowdlerised version was eventually performed under a new title, Katerina Izmailova, on 8 January 1963. The anti-Shostakovich campaign also served as a signal to artists working in other fields, including art, architecture, the theatre and cinema, with the writer Mikhail Bulgakov, the director Sergei Eisenstein, and the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold among the prominent targets. More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of the composer’s friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed. These included Tukhachevsky (shot months after his arrest); his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks (a distinguished physicist, who was eventually released but died before he got home); his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; shot shortly after his arrest); his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar (sent to a camp in Karaganda); his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova (20 years in camps); his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed). His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; his son Maxim was born two years later.

Withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony

The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony. The work marked a great shift in style, owing to the substantial influence of Mahler and a number of Western-style elements. The symphony gave Shostakovich compositional trouble, as he attempted to reform his style into a new idiom. He was well into the work when the Pravda article appeared. He continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but after a number of rehearsals, for reasons still debated today, decided to withdraw the symphony from the public. A number of his friends and colleagues, such as Isaak Glikman, have suggested that it was an official ban that Shostakovich was persuaded to present as a voluntary withdrawal.[30] Whatever the case, it seems possible that this action saved the composer’s life: during this time Shostakovich feared for himself and his family. Yet he did not repudiate the work; it retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. A piano reduction was published in 1946,[31] and the work was finally premiered in 1961, well after Stalin’s death.

During 1936 and 1937, in order to maintain as low a profile as possible between the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, Shostakovich mainly composed film music, a genre favored by Stalin and lacking in dangerous personal expression.

Fifth Symphony and return to favor

The composer’s response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was musically more conservative than his earlier works. Premiered on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad, it was a phenomenal success. The Fifth brought many to tears and welling emotions. Later, Shostakovich’s purported memoir, Testimony, stated: “I’ll never believe that a man who understood nothing could feel the Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood, they understood what was happening around them and they understood what the Fifth was about.”

The success put Shostakovich in good standing once again. Music critics and the authorities alike, including those who had earlier accused him of formalism, claimed that he had learned from his mistakes and become a true Soviet artist. In a newspaper article published under Shostakovich’s name, the Fifth was characterized as “A Soviet artist’s creative response to just criticism.” The composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who had been among those who disassociated themselves from Shostakovich when the Pravda article was published, praised the Fifth and congratulated Shostakovich for “not having given in to the seductive temptations of his previous ‘erroneous’ ways.”

It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. His chamber works allowed him to experiment and express ideas that would have been unacceptable in his more public symphonies. In September 1937 he began to teach composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, which provided some financial security.

Second World War

In 1939, before Soviet forces attempted to invade Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, the Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army paraded through Helsinki. The Winter War was a bitter experience for the Red Army, the parade never happened, and Shostakovich never laid claim to the authorship of this work. It was not performed until 2001. After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist in the military but was turned away because of his poor eyesight. To compensate, he became a volunteer for the Leningrad Conservatory’s firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to the Soviet people. The photograph for which he posed was published in newspapers throughout the country.

His most famous wartime contribution was the Seventh Symphony. The composer wrote the first three movements in Leningrad and completed the work in Kuibyshev (now Samara), where he and his family had been evacuated. It remains unclear whether Shostakovich really conceived the idea of the symphony with the siege of Leningrad in mind. It was officially claimed as a representation of the people of Leningrad’s brave resistance to the German invaders and an authentic piece of patriotic art at a time when morale needed boosting. The symphony was first premiered by the Bolshoi Theatre orchestra in Kuibyshev and was soon performed abroad in London and the United States. It was subsequently performed for broadcast in Leningrad while the city was still under siege. The orchestra had only 14 musicians left, so the conductor Karl Eliasberg had to recruit anyone who could play an instrument to perform.

The family moved to Moscow in spring 1943. At the time of the Eighth Symphony‘s premiere, the tide had turned for the Red Army. As a consequence, the public, and most importantly the authorities, wanted another triumphant piece from the composer. Instead, they got the Eighth Symphony, perhaps the ultimate in sombre and violent expression in Shostakovich’s output. In order to preserve Shostakovich’s image (a vital bridge to the people of the Union and to the West), the government assigned the name “Stalingrad” to the symphony, giving it the appearance of mourning of the dead in the bloody Battle of Stalingrad. But the piece did not escape criticism. Its composer is reported to have said: “When the Eighth was performed, it was openly declared counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet. They said, ‘Why did Shostakovich write an optimistic symphony at the beginning of the war and a tragic one now? At the beginning, we were retreating and now we’re attacking, destroying the Fascists. And Shostakovich is acting tragic, that means he’s on the side of the fascists.'” The work was unofficially but effectively banned until 1956.

The Ninth Symphony (1945), in contrast, was much lighter in tone. Gavriil Popov wrote that it was “splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!” But by 1946 it too was the subject of criticism. Israel Nestyev asked whether it was the right time for “a light and amusing interlude between Shostakovich’s significant creations, a temporary rejection of great, serious problems for the sake of playful, filigree-trimmed trifles.” The New York World-Telegram of 27 July 1946 was similarly dismissive: “The Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner”. Shostakovich continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio (Op. 67), dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a bittersweet, Jewish-themed totentanz finale. In 1947, the composer was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.

Second denunciation

In 1948, Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree. Andrei Zhdanov, Chairman of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, accused the composers (including Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian) of writing inappropriate and formalist music. This was part of an ongoing anti-formalism campaign intended to root out all Western compositional influence as well as any perceived “non-Russian” output. The conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee’s Decree “On V. Muradeli’s opera The Great Friendship“, which targeted all Soviet composers and demanded that they write only “proletarian” music, or music for the masses. The accused composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public apologies in front of the committee. Most of Shostakovich’s works were banned, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says that at this time “he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn’t be disturbed.”

The decree’s consequences for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was among those dismissed from the Conservatory altogether. For him, the loss of money was perhaps the largest blow. Others still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere thick with suspicion. No one wanted his work to be understood as formalist, so many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing anti-proletarian music.

During the next few years Shostakovich composed three categories of work: film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works “for the desk drawer”. The latter included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the postwar anti-Semitic campaign was already under way, with widespread arrests, including that of Dobrushin and Yiditsky, the compilers of the book from which Shostakovich took his texts.

The restrictions on Shostakovich’s music and living arrangements were eased in 1949, when Stalin decided that the Soviets needed to send artistic representatives to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York City, and that Shostakovich should be among them. For Shostakovich, it was a humiliating experience, culminating in a New York press conference where he was expected to read a prepared speech. Nicolas Nabokov, who was present in the audience, witnessed Shostakovich starting to read “in a nervous and shaky voice” before he had to break off “and the speech was continued in English by a suave radio baritone”. Fully aware that Shostakovich was not free to speak his mind, Nabokov publicly asked him whether he supported the then recent denunciation of Stravinsky’s music in the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Stravinsky who had been influenced by his music, Shostakovich had no alternative but to answer in the affirmative. Nabokov did not hesitate to write that this demonstrated that Shostakovich was “not a free man, but an obedient tool of his government.” Shostakovich never forgave Nabokov for this public humiliation. That same year he was obliged to compose the cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the “great gardener”.

Stalin’s death in 1953 was the biggest step toward Shostakovich’s rehabilitation as a creative artist, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and Elmira motifs, Elmira Nazirova being a pianist and composer who had studied under Shostakovich in the year before his dismissal from the Moscow Conservatory), the meaning of which is still debated, while the savage second movement, according to Testimony, is intended as a musical portrait of Stalin. The Tenth ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of Shostakovich’s most popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the “desk drawer” works.

During the forties and fifties, Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils, Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. In the background to all this remained Shostakovich’s first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in 1954. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1939 to 1941 and then from 1947 to 1948. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as “tender”. Ustvolskaya rejected a proposal of marriage from him after Nina’s death.[59] Shostakovich’s daughter, Galina, recalled her father consulting her and Maxim about the possibility of Ustvolskaya becoming their stepmother. Ustvolskaya’s friend Viktor Suslin said that she had been “deeply disappointed” in Shostakovich by the time of her graduation in 1947.[citation needed] The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one-sided, expressed largely in his letters to her, and can be dated to around 1953 to 1956. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill-matched, and divorced five years later.

In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96; it was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics. (His ‘”Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale” was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.)

In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union). Later that year, Bernstein and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony in Boston for Columbia Records.

Joining the Party

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich’s life: he joined the Communist Party. The government wanted to appoint him General Secretary of the Composers’ Union, but in order to hold that position he was required to attain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1953 to 1964, was looking for support from the intelligentsia’s leading ranks in an effort to create a better relationship with the Soviet Union’s artists. This event has variously been interpreted as a show of commitment, a mark of cowardice, the result of political pressure, or his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was undoubtedly less repressive than it had been before Stalin’s death. On the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to tears, and that he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed. Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal. From 1962, he served as a delegate in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Once he joined the Party, several articles he did not write denouncing individualism in music were published under his name in Pravda. By joining the party, Shostakovich also committed himself to finally writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in 1961, was dedicated to Lenin and called “The Year 1917.” Around this time, his health began to deteriorate. Shostakovich in 1950

Shostakovich’s musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet, composed in only three days. He subtitled the piece “To the victims of fascism and war”, ostensibly in memory of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945. Yet like the Tenth Symphony, the quartet incorporates quotations from several of his past works and his musical monogram. Shostakovich confessed to his friend Isaak Glikman, “I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself.” Several of Shostakovich’s colleagues, including Natalya Vovsi-Mikhoelsand the cellist Valentin Berlinsky, were also aware of the Eighth Quartet’s biographical intent. Peter J. Rabinowitz has also pointed to covert references to Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen in it.

In 1962 Shostakovich married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to Glikman, he wrote, “her only defect is that she is 27 years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful, straightforward and very likeable.”According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one: “It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic peace… Surely, she prolonged his life by several years.” In November he made his only venture into conducting, conducting a couple of his own works in Gorky;otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health.

That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti-Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of Ukrainian Jews during the Second World War. Opinions are divided as to how great a risk this was: the poem had been published in Soviet media, and was not banned, but remained controversial. After the symphony’s premiere, Yevtushenko was forced to add a stanza to his poem that said that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.

In 1965 Shostakovich raised his voice in defence of poet Joseph Brodsky, who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich co-signed protests with Yevtushenko, fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. After the protests the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad.

Later life, and death

In 1964 Shostakovich composed the music for the Russian film Hamlet, which was favourably reviewed by The New York Times: “But the lack of this aural stimulation—of Shakespeare’s eloquent words—is recompensed in some measure by a splendid and stirring musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich. This has great dignity and depth, and at times an appropriate wildness or becoming levity”.

In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka. Beginning in 1958 he suffered from a debilitating condition that particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up piano playing; in 1965 it was diagnosed as poliomyelitis. He also suffered heart attacks the following year and again in 1971, and several falls in which he broke both his legs; in 1967 he wrote in a letter: “Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order.”

A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich’s later works, such as the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death). This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical language, with 12-tone themes and dense polyphony throughout. He dedicated the Fourteenth to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer’s own Fourth Symphony.

Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975. A civic funeral was held; he was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow. Even before his death he had been commemorated with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica. Despite suffering from Motor Neurone Disease (or ALS) from as early as the 1960s, Shostakovich insisted upon writing all his own correspondence and music himself, even when his right hand was virtually unusable.Shostakovich voting in the election of the Council of Administration of Soviet Musicians in Moscow in 1974

He was survived by his third wife, Irina; his daughter, Galina; and his son, Maxim, a pianist and conductor who was the dedicatee and first performer of some of his father’s works. Shostakovich himself left behind several recordings of his own piano works; other noted interpreters of his music include Emil Gilels, Mstislav Rostropovich, Tatiana Nikolayeva, Maria Yudina, David Oistrakh, and members of the Beethoven Quartet.

His last work was his Viola Sonata, which was first performed officially on 1 October 1975.

Shostakovich’s musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn‘s music shows clear links to Shostakovich’s style of orchestration. His influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars-Erik Larsson. Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Sergei Slonimsky, and Boris Tishchenko, whose 5th Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich’s memory). Shostakovich’s conservative idiom has grown increasingly popular with audiences both within and outside Russia, as the avant-garde has declined in influence and debate about his political views has developed. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Shostakovich

Dmitri (Dmitrijevitsj) Sjostakovitsj was een Russische componist. Hij is vooral bekend om zijn symfonieën en strijkkwartetten.

Jeugd

Dmitri Dmitrijevitsj Sjostakovitsj werd op 25 september 1906 te Sint-Petersburg geboren. Vanaf zijn negende kreeg hij pianolessen. Hij bleek een talent: al op zijn dertiende werd hij toegelaten tot het Conservatorium van Sint-Petersburg. In 1925 studeerde hij af met de succesvolle première van zijn Eerste symfonie.

Sjostakovitsj en de staat

De Eerste symfonie was nog redelijk tonaal, maar hierna ging Sjostakovitsj al snel experimenteren. In de Tweede symfonie uit 1927, bijnaam ‘Oktober’, zitten de noten zo dicht tegen elkaar dat het soms moeilijk is een bepaalde melodie te ontdekken. Het past in de ideologie van de muzikale avant-garde van de Sovjet-Unie in deze tijd.

Onder Stalin, die sinds de dood van Lenin in 1924 steeds meer macht naar zich toe wist te trekken, kwam aan dit soort experimentele uitspattingen een einde. Volgens de dictator moest alle kunst te begrijpen zijn voor de gemiddelde arbeider en een positief beeld van de socialistische toekomst uitdragen: dit propagandagenre werd door het regime ‘socialistisch realisme’ genoemd.

In 1936 verscheen in de Pravda (‘Waarheid’, het partijblad) een artikel met de naam ‘Chaos in plaats van muziek’. Hierin werd Sjostakovitsj’ opera Lady MacBeth uit het district Mtsensk door het slijk gehaald om het ‘negatieve’ libretto, de ‘bourgeois innovaties’ en de ‘expres dissonante, verwarde stroom geluid’.

Sjostakovitsj haalde onmiddellijk zijn al voltooide Vierde symfonie van het programma en componeerde nooit meer een opera. Een jaar later bracht hij zijn Vijfde symfonie ten gehore. Hoewel dit werk een stuk helderder en minder dissonant was dan Lady MacBeth, wist Sjostakovitsj toch een eigen stijl te behouden. Het sovjetregime waardeerde de ommekeer en de naam van de componist was voorlopig gezuiverd.

Desondanks bleef Sjostakovitsj het moeilijk hebben onder Stalin. Hij moest bij aanvang van de Tweede Wereldoorlog voortdurend opdraven met muziek over de triomfen van het Rode Leger, en had weinig artistieke vrijheid. Als zijn Achtste en Negende symfonie het levenslicht zien groeit de kritiek opnieuw: de Achtste symfonie is te treurig – terwijl het Rode Leger eindelijk de overhand krijgt – en de Negende symfonie is ‘ongepast, kinderlijk vrolijk’, zo kort na de Tweede Wereldoorlog.

Met de invoering van de Zjdanovbeleid in 1948 – gebaseerd op een doctrine van politicus Sergej Zjdanov, die voorschreef dat iedere kunstenaar volkomen naar het denkbeeld van de Sovjetunie moest handelen – kreeg Sjostakovitsj een officiële waarschuwing. Als gevolg verloor hij zijn functie aan het conservatorium van Moskou en zat hij zonder inkomen.

Sjostakovitsj trok zich terug en componeerde bijna alleen nog filmmuziek ‘om de rekeningen te betalen’. De rest belandde in de la van zijn bureau, uit angst dat er iets verkeerds in zou worden gehoord.

Volgens Stalin moest alle kunst te begrijpen zijn voor de gemiddelde arbeider en een positief beeld van de socialistische toekomst uitdragen

Pas na de dood van Stalin in 1953 keerde Sjostakovitsj terug in de concertzaal. Zijn kenmerkende chromatische, dissonante stijl keerde ook terug, hoewel de basis van zijn stukken veelal tonaal bleef. Dit is goed te horen in het bekende Achtste strijkkwartet. Na Stalin’s dood kon Sjostakovitsj makkelijker naar het westen; hij bezocht zowel Engeland als de Verenigde Staten en legde contacten met Benjamin Britten en Leonard Bernstein.

Liefde en dood

Sjostakovitsj trouwde liefst drie keer. Met zijn eerste vrouw, Nina Vazar, kreeg hij twee kinderen. Zij overleed in 1954, na 22 jaar huwelijk, aan kanker. Zijn tweede huwelijk, met Margarita Kainova, hield drie jaar stand. In 1962 hertrouwde Sjostakovitsj opnieuw, met Irina Soepinskaja. Zij bleven samen tot zijn dood.

Op 9 augustus 1975 overleed Sjostakovitsj aan de gevolgen van longkanker. Hij kreeg een staatsbegrafenis. https://www.preludium.nl/dmitri-sjostakovitsj

The film recounts the life of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich from the perspective of a film director, played by Armin Mueller-Stahl, who is shooting a movie about Shostakovich. While editing the film, the director shifts through scenes from feature films for which Shostakovich wrote the music during the rule of Stalin. The director meets and interviews family members and companions of the composer, such as Mstislav Rostropovich. Key moments in the life of Shostakovich are re-enacted with marionette puppets. At the end of his investigation, the director realises that he is unable to draw a clear-cut portrait of the composer – what his interview partners tell him is just too contradictory. A film by Oliver Becker and Katharina Bruner

Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 (1912-1913; lost during the Russian Revolution of 1917, the score was rewritten by Prokofiev in 1923-1924.)