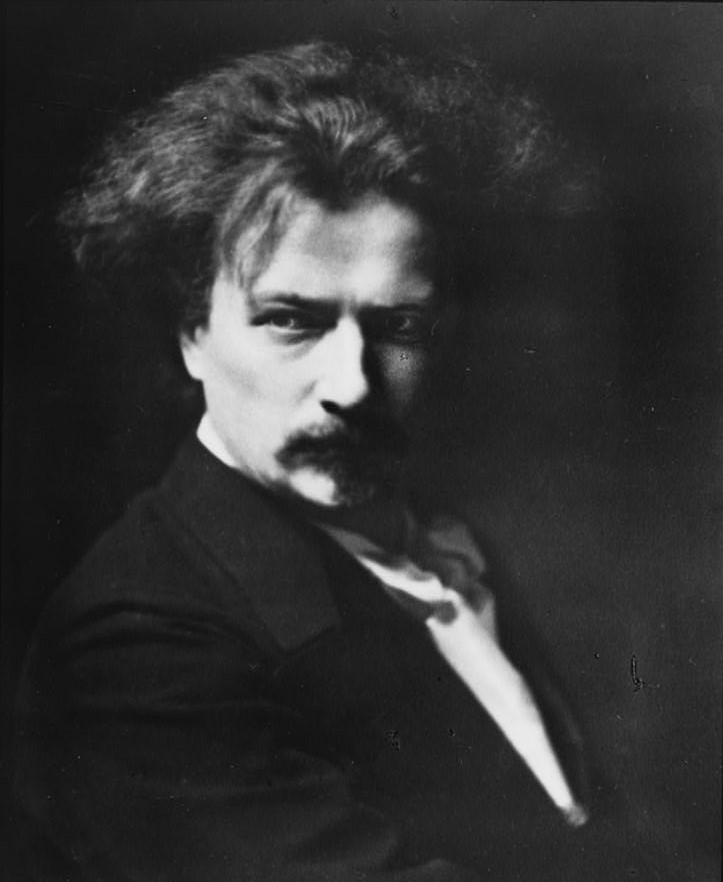

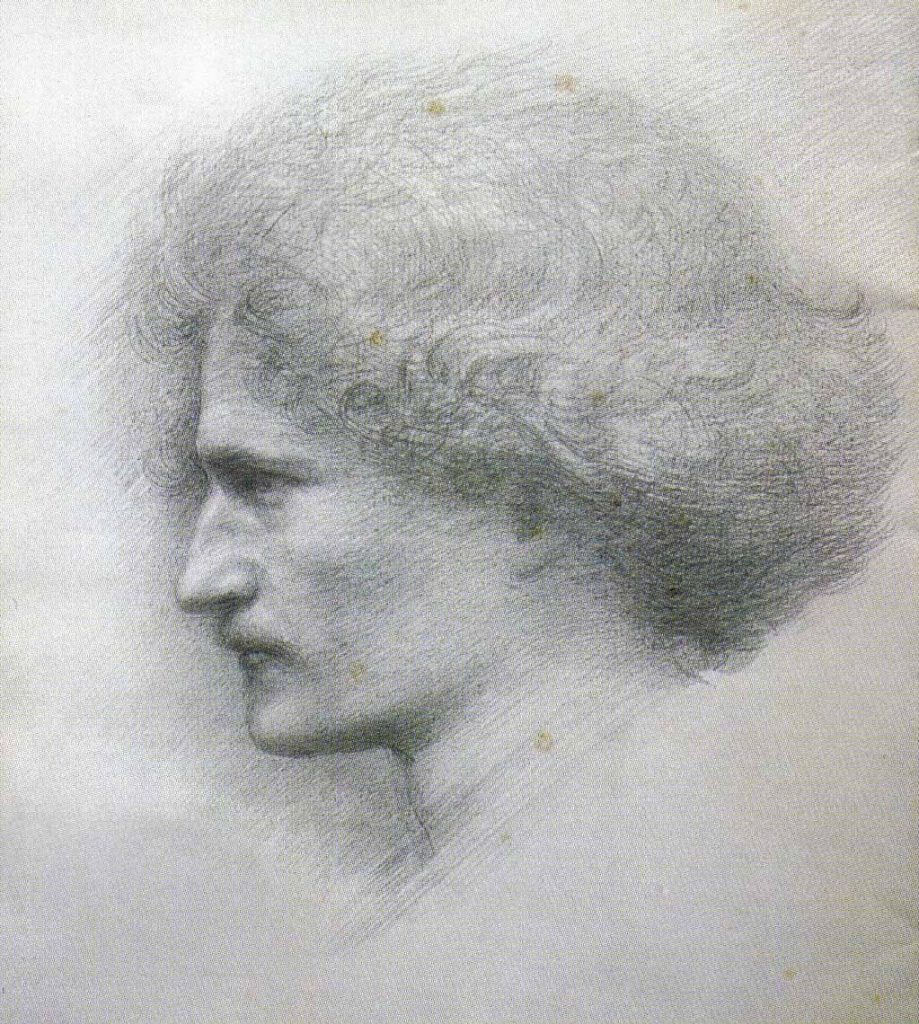

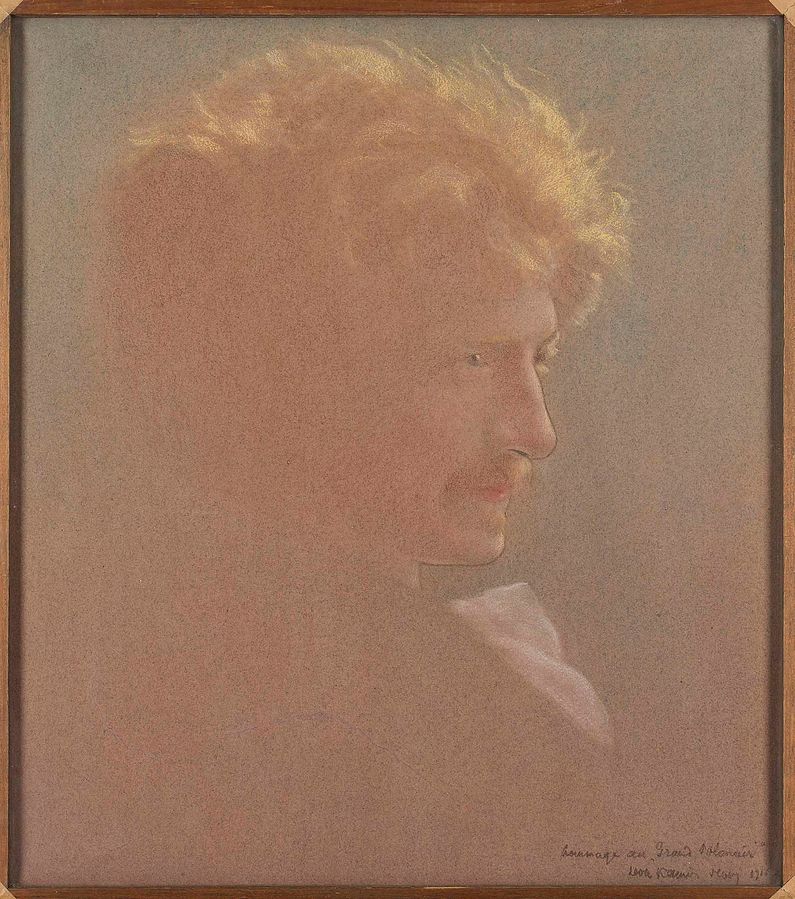

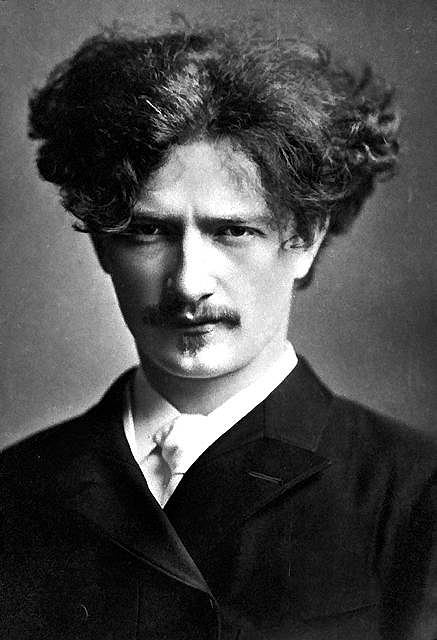

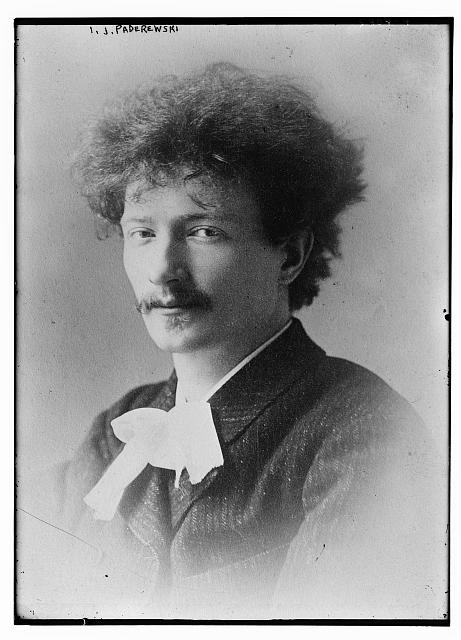

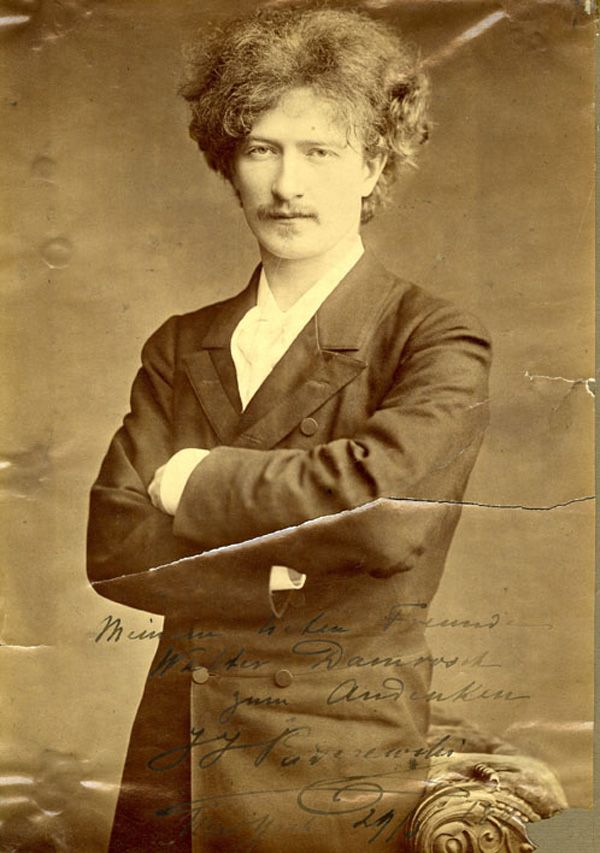

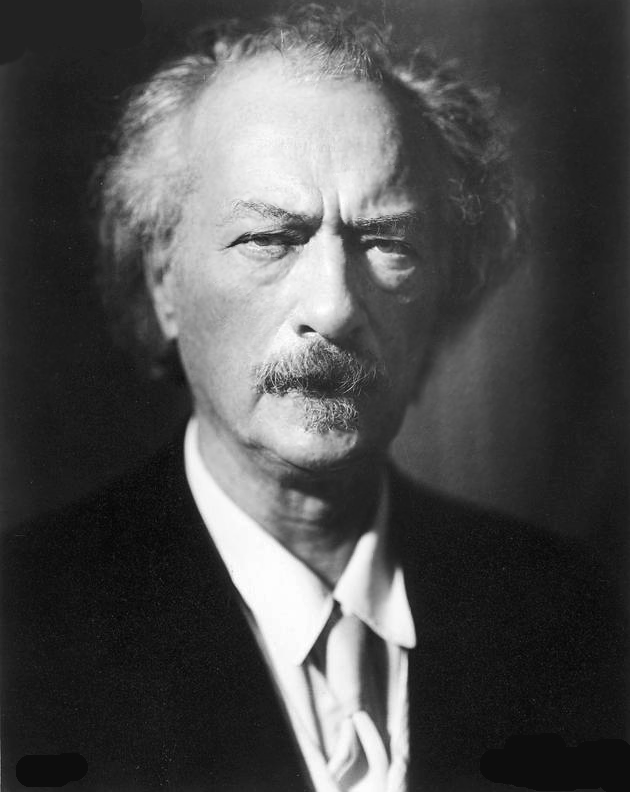

Hij inspireerde kunstenaars, dichters, schilders en componisten. Het beroemdste portret van hem is gemaakt door Sir Edward Burne-Jones, die hem toevallig op een dag op straat passeerde. Hij ging naar huis en zei dat hij de ‘archangel'(aartsengel) had gezien en begon uit zijn hoofd te schetsen. Een paar dagen later werd Paderewski door een van zijn vrienden naar de studio van Burne Jones gebracht, waar deze verschillende schetsen van hem maakte. In twee uur was het portret klaar. Byrne Jones noemde hem een ‘An Archangel with a splendid halo of golden hair’. https://www.muziekbus.nl/muziek/ignacy+jan+paderewski.html

Ignacy Jan Paderewski 18 November [O.S. 6 November] 1860 – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation’s Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I.

A favorite of concert audiences around the world, his musical fame opened access to diplomacy and the media, as possibly did his status as a freemason, and charitable work of his second wife, Helena Paderewska. During World War I, Paderewski advocated an independent Poland, including by touring the United States, where he met with President Woodrow Wilson, who came to support the creation of an independent Poland in his Fourteen Points at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, which led to the Treaty of Versailles.

Shortly after his resignations from office, Paderewski resumed his concert career to recoup his finances and rarely visited the politically-chaotic Poland thereafter, the last time being in 1924.

Paderewski was born to Polish parents in the village of Kuryłówka (Kurilivka), Litin uyezd, in the Podolia Governorate of the Russian Empire. The village had been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth for centuries and now is part of the Khmilnyk raion of Vinnytsia Oblast in Ukraine. His father, Jan Paderewski, administered large estates. His mother, Poliksena, née Nowicka, died several months after Paderewski was born, and he was raised mostly by distant relatives.

From his early childhood, Paderewski was interested in music. He initially lived at a private estate near Żytomir, where he moved with his father. However, soon after his father’s arrest in connection with the January Uprising (1863), he was adopted by his aunt. After being released, Paderewski’s father married again and moved to the town of Sudylkov, near Shepetovka.

Initially, Paderewski took piano lessons with a private tutor. At the age of 12, in 1872, he went to Warsaw and was admitted to the Warsaw Conservatory. Upon graduating in 1878, he became a tutor of piano classes at his alma mater. In 1880, Paderewski married a fellow student at the conservatory, Antonina Korsakówna. The next year, their son Alfred was born severely handicapped. Antonina never recovered from childbirth and died several weeks later. Paderewski decided to devote himself to music and left his son in the care of friends, and in 1881, he went to Berlin to study music composition with Friedrich Kiel and Heinrich Urban.

A chance meeting in 1884 with a famous Polish actress, Helena Modrzejewska, began his career as a virtuoso pianist. Modrzejewska arranged for a public concert and joint appearance in Kraków’s Hotel Saski to raise funds for Paderewski’s further piano study. The scheme was a tremendous success, and Paderewski soon moved to Vienna, where he studied with Theodor Leschetizky (Teodor Leszetycki). He married his second wife, Helena Paderewska (née von Rosen)(1856–1934), shortly after she received an annulment of a prior marriage, on 31 May 1899. While she had previously cared for his son Alfred (1880–1901), they had no children together.

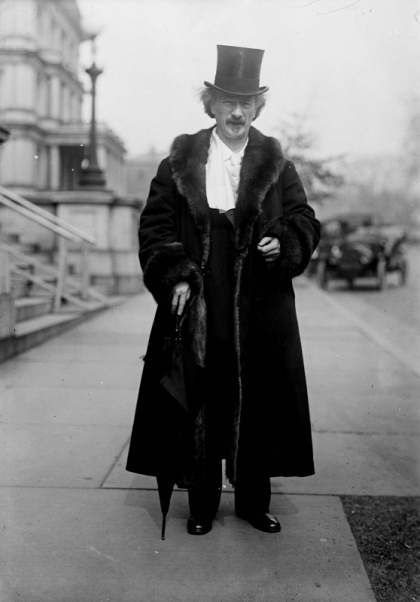

After three years of diligent study and a teaching appointment in Strasbourg which Leschetizky arranged, Paderewski made his concert debut in Vienna in 1887. He soon gained great popularity and had popular successes in Paris in 1889 and in London in 1890. Audiences responded to his brilliant playing with almost extravagant displays of admiration, and Paderewski also gained access to the halls of power. In 1891, Paderewski repeated his triumphs on an American tour; he would tour the country more than 30 times for the next five decades, and it would become his second home. His stage presence, striking looks, and immense charisma contributed to his stage success, which later proved important in his political and charitable activities. His name became synonymous with the highest level of piano virtuosity. Not everyone was equally impressed, however. After hearing Paderewski for the first time, Moriz Rosenthal quipped, “Yes, he plays well, I suppose, but he’s no Paderewski.”

Paderewski kept up a furious pace of touring and composition, including many of his own piano compositions in his concerts. He also wrote an opera, Manru, which is still the only opera by a Polish composer that was ever performed in the Metropolitan Opera‘s 135-year history. A “lyric drama,” Manru is an ambitious work that was formally inspired by Wagner’s music dramas. It lacks an overture and closed-form arias but uses Wagner’s device of leitmotifs to represent characters and ideas. The story centres on a doomed love triangle, social inequality, and racial prejudice (Manru is a Gypsy), and it is set in the Tatra Mountains. In addition to the Met, Manru was staged in Dresden (a private royal viewing), Lviv (its official premiere in 1901), Prague, Cologne, Zurich, Warsaw, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh and Baltimore, Moscow, and Kiev. In 1904, Paderewski, accompanied by his second wife, entourage, parrot, and Erard piano, gave concerts in Australia and New Zealand in collaboration with Polish-French composer, Henri Kowalski. Paderewski toured tirelessly around the world and was the first to give a solo performance at the new 3,000-seat Carnegie Hall. In 1909 came the premiere of his Symphony in B minor “Polonia”, a massive work lasting 75 minutes. Paderewski’s compositions were quite popular during his lifetime and, for a time, entered the orchestral repertoire, particularly his Fantaisie polonaise sur des thèmes originaux (Polish Fantasy on Original Themes) for piano and orchestra, Piano Concerto in A minor, and Polonia symphony. His piano miniatures became especially popular; the Minuet in G major, Op. 14 No. 1, written in the style of Mozart, became one of the most recognized piano tunes of all time. Despite his relentless touring schedule and his political and charitable engagements, Paderewski left a legacy of over 70 orchestral, instrumental, and vocal works.

In 1913, Paderewski settled in the United States. On the eve of World War I and at the height of his fame, Paderewski bought a 2,000-acre (810-ha) property, Rancho San Ignacio, near Paso Robles, in San Luis Obispo County, in California’s Central Coast region. A decade later, he planted Zinfandel vines on the Californian property. When the vines matured, the grapes were processed into wine at the nearby York Mountain Winery, which was, as it still is, one of the best-known wineries between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

In 1910, Paderewski funded the Battle of Grunwald Monument in Kraków to commemorate the battle’s 500th anniversary. The monument’s unveiling led to great patriotic demonstrations. In speaking to the gathered throng, Paderewski proved as adept at capturing their hearts and minds for the political cause as he was with his music. His passionate delivery needed no recourse to notes. Paderewski’s status as an artist and philanthropist and not as a member of any of the many Polish political factions became one of his greatest assets and so he rose above the quarrels, and he could legitimately appeal to higher ideals of unity, sacrifice, charity, and work for common goals.

During World War I, Paderewski became an active member of the Polish National Committee in Paris, which was soon accepted by the Triple Entente as the representative of the forces trying to create the state of Poland. Paderewski became the committee’s spokesman, and soon, he and his wife also formed others, including the Polish Relief Fund, in London, and the White Cross Society, in the United States. Paderewski met the English composer Edward Elgar, who used a theme from Paderewski’s Fantasie Polonaise[15] in his work Polonia written for the Polish Relief Fund concert in London on 6 July 1916 (the title certainly recognises Paderewski’s Symphony in B minor).

Paderewski urged fellow Polish immigrants to join the Polish armed forces in France, and he pressed elbows with all the dignitaries and influential men whose salons he could enter. He spoke to Americans directly in public speeches and on the radio by appealing to them to remember the fate of his nation. He kept such a demanding schedule of public appearances, fundraisers, and meetings that he stopped musical touring altogether for a few years, instead dedicating himself to diplomatic activity. On the eve of the American entry into the war, in January 1917, US President Woodrow Wilson’s main advisor, Colonel House, turned to Paderewski to prepare a memorandum on the Polish issue. Two weeks later, Wilson spoke before Congress and issued a challenge to the status quo: “I take it for granted that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, autonomous Poland.” The establishment of “New Poland” became one of Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points, the principles that Wilson followed during peace negotiations to end World War I. In April 1918, Paderewski met in New York City with leaders of the American Jewish Committee in an unsuccessful attempt to broker a deal in which organised Jewish groups would support Polish territorial ambitions, in exchange for support for equal rights. However, it soon became clear that no plan would satisfy both Jewish leaders and Roman Dmowski, the head of the Polish National Committee, who was strongly anti-Semitic.

At the end of the war, with the fate of the city of Poznań and the whole region of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) still undecided, Paderewski visited Poznań. With his public speech on 27 December 1918, the Polish inhabitants of the city began a military uprising against Germany, called the Greater Poland Uprising. Behind the scenes, Paderewski worked hard to get Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski to collaborate, but the latter came on top.Monument to Paderewski in Warsaw’s Ujazdów Park

In 1919, in the newly independent Poland, Piłsudski, who was the Chief of State, appointed Paderewski as the Prime Minister of Poland and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland (January 1919 – December 1919). He and Dmowski represented Poland at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and dealt with issues regarding territorial claims and minority rights. He signed the Treaty of Versailles, which recognized Polish independence won after World War I, and the subsequent Soviet invasion was halted.

Paderewski’s government achieved remarkable milestones in just ten months: democratic elections to Parliament, ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, passage of the treaty on protection of ethnic minorities in the new state and the establishment of a public education system. It also tackled border disputes, unemployment, ethnic and social strife, the outbreak of epidemics and averted the looming famine after the devastation of war. After the elections, Paderewski resigned as prime minister but continued to represent Poland abroad at international conferences and at the League of Nations. Thanks to his diplomatic skills (he was the only delegate who was not assigned a translator since he was fluent in seven languages) and great personal esteem, Poland was able to negotiate thorny issues with its Ukrainian and German neighbours and gain international respect in the process.

In 1922, Paderewski retired from politics and returned to his musical life. His first concert after a long break, held at Carnegie Hall, was a significant success. He also filled Madison Square Garden (20,000 seats) and toured the United States in a private railway car. His manor house (bought in 1897) in Kąśna Dolna near Tarnów in Poland

In 1897, Paderewski had bought the manor house of the former Duchess of Otrante near Morges, Switzerland, where he rested between concert tours. After Piłsudski’s coup d’état in 1926, Paderewski became an active member of the opposition to Sanacja rule. In 1936, two years after his second wife’s death at their Swiss home, a coalition of members of the opposition met in the mansion and was nicknamed the Front Morges after the village.

By 1936, Paderewski agreed to appear in a film that presented his talent and art. Although the proposal had come while the mourning Paderewski avoided public appearances, the film project went ahead. It became notable, primarily, for its rare footage of his piano performance. The exiled German-born director Lothar Mendes directed the feature, which was released in Britain as Moonlight Sonata in 1937 and re-titled The Charmer for US distribution in 1943.

In November 1937, Paderewski agreed to take on one last piano student. The musician was Witold Małcużyński, who had won third place at the International Chopin Piano Competition

After the Polish Defensive War in 1939, Paderewski returned to public life. In 1940, he became the head of the National Council of Poland, a Polish sejm (parliament) in exile in London. He again turned to America for help and spoke to its people directly over the radio, the most popular media at the time; the broadcast carried by over 100 radio stations in the United States and Canada. In late 1940, he spent a couple of weeks in Portugal, before returning to the United States. He stayed in Estoril, at the Hotel Palácio, between 8 October and 27 October 1940. Afterwards, he crossed the Atlantic again to advocate in person for European aid and to defeat Nazism. In 1941, Paderewski witnessed a touching tribute to his artistry and humanitarianism as US cities celebrated the 50th anniversary of his first American tour by putting on a Paderewski Week, with over 6000 concerts in his honour. The 80-year-old artist also restarted his Polish Relief Fund and gave several concerts to gather money for it. However, his mind was not what it had once been, and scheduled again to play Madison Square Garden, he refused to appear and insisted that he had already played the concert; he was presumably remembering the concert he had played there in the 1920s. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignacy_Jan_Paderewski

Composed in 1882, the Violin Sonata is arguably the finest of Paderewski’s earlier works. The first movement starts with an eloquent theme for the violin over an intricate piano accompaniment, at length making way for a more resolute and rhythmically defined theme as takes the exposition through to its engaging close. After a formal repeat, the development looks to the movement’s ‘fantasia’ marking with its free-wheeling and inventive discussion of both themes, following which there is a modified reprise – the initial theme now unfolding at greater length – then a coda which draws on aspects of both themes prior to the regretful close. The second movement, marked Intermezzo, begins with halting exchanges between the two instruments, out of which a gently expressive theme emerges which takes on greater substance before the piano makes a return to the initial exchanges. From here the main theme resumes, touching on greater heights of expressiveness before reaching its winsome close. The third movement sets off with a fervent theme that briefly yields to one of greater repose before continuing on its charged course. After a repeat of the exposition, the development makes resourceful use of both themes, with the violin’s dextrous pizzicato complementing the piano’s limpid passagework, before a heightened reprise which throws the character of both themes into greater relief, followed by a coda that sees the work through to its decisive close. (Naxos Music Library) Please take note that the audio AND sheet music ARE NOT mine. Change the quality to a minimum of 480p if the video is blurry. Original audio: naxosmusiclibrary.com (Performance by: Adam Kostecki at the violin, accompanied by Gunther Hauer) Original sheet music: http://imslp.org/wiki/Violin_Sonata,_…)

Adam Kostecki (* 1948 in Polen) ist ein deutscher Violinist polnischer Herkunft und Orchesterleiter sowie Hochschullehrer an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hannover.

Kostecki ist ein Schüler von Boris Bielenkij, bei dem er 1967 bis 1972 am Moskauer Konservatorium studierte (zu seinen Lehrern gehörte auch David Oistrach). Außerdem besuchte er Kurse bei Isaac Stern, Henryk Szeryng, Nathan Milstein und Yehudi Menuhin. Ab 1972 war er als Musiker in verschiedenen westdeutschen Orchestern. Neben seiner Orchestertätigkeit (ab 1982 als erster Konzertmeister am Niedersächsischen Staatsorchester) trat er als Solist (zuerst 1967 mit dem Warschauer Philharmonischen Orchester) und in Kammerorchestern auf (Rubinstein-Trio, gegründet in Lodz, mit dem Cellisten Stanislaw Firlej und der Pianistin Anna Wesolowska, Paganini-Duo mit dem Gitarristen Carsten Petermann).

1984 bis 1990 war er Solist und stellvertretender künstlerischer Leiter (unter dem Leiter Wojciech Rajski) der Polnischen Kammerphilharmonie und 1990 wurde er Leiter des Kammerorchesters Hannover. 1992 wurde er Professor für Violine an der Musikhochschule Hannover.

Außer in Europa trat er unter anderem in Brasilien, Uruguay, China, Japan und Korea auf.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycs2CoNDKo4