The sharks and the bees: what nature’s patterns teach us about sourcing

A pattern called the Lévy walk has been found all over nature, and humans’ habits mimic the paradigm in surprising ways

“Although human subtlety makes a variety of inventions by different means to the same end, it will never devise an invention more beautiful, more simple, or more direct than does nature, because in her inventions nothing is lacking, and nothing is superfluous.”

When sharks, honeybees and other animals forage for food, they move in a pattern of short movements in one area combined with a few longer treks to more distant areas. This pattern is called Lévy walks (or flights).

A National Academy of Sciences study released last month, “Evidence of Lévy walk foraging patterns in human hunter–gatherers”, also found that the Hadza, hunter-gatherers from northern Tanzania, perform Lévy walks when foraging for a wide variety of food items.

The authors suggest that this type of movement profile is a “fundamental feature of human landscape use, regardless of the physical or cultural environment, and may have played an important role in the evolution of human mobility”.

We can see the same kind of pattern closer to home: in Saturday Night Fever and HBO’s Girls, young people seek their mates in their local Brooklyn neighborhoods, with an occasional jaunt to Manhattan. And in Law & Order: Criminal Intent, brilliant detective Robert Goren often solves the crime by identifying the movement patterns of serial murderers.

Nature, our subconscious master, is very, very powerful. Nature’s intricate web is the genius embedded in every breath we take and every morsel we eat. It’s incumbent upon us to start looking more closely at its patterns and constraints.

Many scientists and investors are already doing this. Janine Benyus, who named the emerging discipline of biomimicry, describes “seeking sustainable solutions by emulating nature’s designs and processes (for instance, solar cells that mimic leaves)”. This new understanding of our movement patterns can help us design everything from our food pipelines to our electricity grids.

It also has implications for business supply chains and sourcing. As commerce grows ever-more global, it’s clear that – like the long treks embedded in honeybee, shark and Hazda foraging patterns – global cooperation, competition and collaboration will remain key to business. All industries, as well as all biological systems and environmental impacts, are intertwined at this point in world history – with many symbiotic advantages. But for the most part, going local is where it’s at.

Decentralizing food and energy sourcing and disposal would make us safer, saner and more in tune with our natural inclinations. It could also reintroduce social exchange into everyday commerce.

Meet the producers

In many US regions, the only option for buying groceries, clothing, hardware or meals is a global mega-chain. Occasionally, these are franchises owned by local businesspeople. More often, these serve to completely separate us from anyone who has cultivated, made or transported our daily bread, our clothing, our gadgets or – even, most of the time – our energy.

Just 50 years ago, shopping in most neighborhoods, both rich and poor, involved buying from a Mr and Mrs Somebody, whose children went to school with their customers’ children. Shopping was a social foray.

Why is Seattle’s Pike Place Market so enticing? As welcome sign says, “Meet the producer.” Why are farmers’ markets, where the produce is often double the cost of mega-chains, on the rise everywhere? This is foraging in the modern age. This kind of shopping fosters a relationship between one’s food and one’s farmer, but remains a speck in the western world’s economic balance sheet.

Some countries, such as India, demand that up to 30% of multibrand retailers’ products be procured from Indian small industries. Walmart is fighting this requirement in India. However, in 2010, Walmart in committed to sourcing $1bn a year of produce from local farmers, and promised a premium price for smaller farms. Walmart’s low pricing remains a contentious issue with its suppliers, but the program has doubled Walmart’s local sourcing to 11% of its total food purchases.

The fact that Walmart even considers the importance of local products gives me a glimmer of hope. Hats off to the activists that forced this issue. It’s up to all of those working in large global business to create sourcing pipelines that allow regional eco and economic systems to support one another, which is no easy task.

Three places to buy local

But here are three areas where local is absolutely preferable to global. Firstly, garbage disposal – you chuck it, you live with it. Secondly, electricity – the closer to the source, the less waste in the transmission grid. And thirdly, water – the more one appreciates its source, the more one protects its sanctity.

The miraculous patterns of nature sustain us, and our natural foraging inclinations propel us in ways that enhance our ability to survive. As the National Academy of Sciences study shows, our movement tendencies are close to other creatures’ in profound and striking ways.

As businesspeople, we cannot ignore these patterns as we strive to both protect and profit from agricultural bounty. These patterns are stronger than the most intricate supply chain created by the smartest Harvard MBAs. Nature means business. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/jan/22/lessons-nature-foraging-patterns-levy-walks-local-sourcing

How organisms improve the search for food, mates, etc., is a key factor to their survival. Mathematically, the best strategy to look for randomly distributed re-visitable resources—under scarce information and sparse conditions—results from Lévy distributions of move lengths (the probability of taking a step ℓ is proportional to 1/ℓ2). Today it is well established that many animal species in different habitats do perform Lévy foraging. This fact has raised a heated debate, viz., the emergent versus evolutionary hypotheses. For the former, a Lévy foraging is an emergent property, a consequence of searcher-environment interactions: certain landscapes induce Lévy patterns, but others not. In this view, the optimal strategy depends on the particular habitat. The evolutionary explanation, in contrast, is that Lévy foraging strategies are adaptations that evolved via natural selection. In this article, through simulations we exhaustively analyze the influence of distinct environments on the foraging efficiency. We find that the optimal procedure is the same in all situations, provided density is low and landscape information is scarce. So, the best search strategy is remarkably independent of details. These results constitute the strongest theoretical evidence to date supporting the evolutionary origins of experimentally observed Lévy walks. https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005774

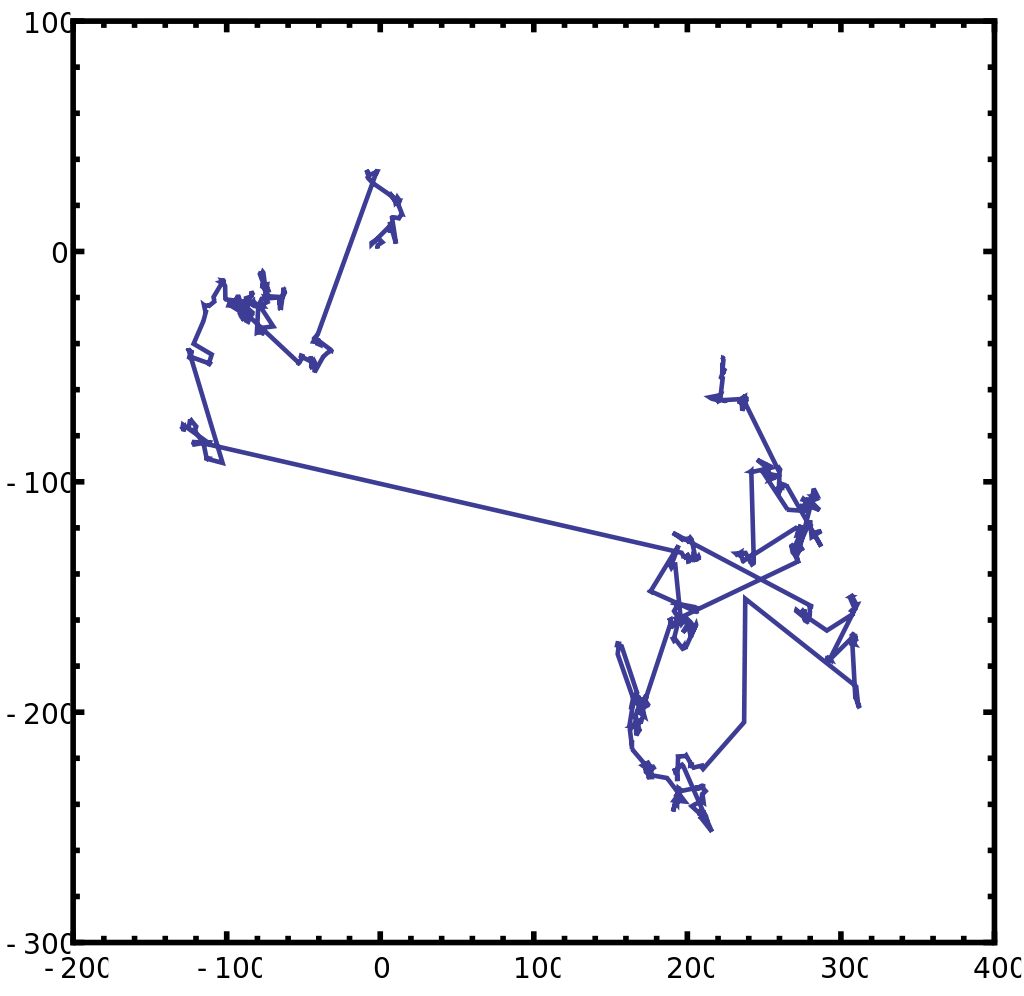

An example of 1000 steps of a Lévy flight in two dimensions. The origin of the motion is at [0,0], the angular direction is uniformly distributed and the step size is distributed according to a Lévy (i.e. stable) distribution with α = 1 and β = 0 which is a Cauchy distribution. Note the presence of large jumps

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A9vy_flight

Een voorbeeld van 1000 stappen van een Lévy-vlucht in twee dimensies. De oorsprong van de beweging is op [0,0], de hoekige bewegingen zijn gelijkmatig verdeeld en de stapgrootte zijn verdeeld volgens een Lévy-vlucht (dat wil zeggen een stabiele) verdeling met α = 1 en β = 0, die een Cauchy-verdeling is. Let op de aanwezigheid van grote sprongen.

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A9vy-vlucht

Above:

Bees, like sharks and Hadza hunter-gatherers, forage in a pattern called Levy walks.Reuters

Photograph JACKY NAEGELEN/Reuters