Bevor Christoph Kolumbus 1492 Amerika für die Europäer „entdeckte“ und einen furchtbaren Genozid an allen indigenen Völkern ins Rollen brachte, lebten die Menschen in kulturellen und ökonomischen Zusammenhängen, über die die meisten Menschen kaum etwas wissen. Dies möchte diese Dokumentarreihe ändern und klärt über das Leben der Menschen vor der Ankunft der Weißen in Amerika auf.

1491 New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

Written by: Charles C. Mann Read by: Darrell Dennis

A groundbreaking study that radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans in 1492.

Traditionally, Americans learned in school that the ancestors of the people who inhabited the Western Hemisphere at the time of Columbus’s landing had crossed the Bering Strait twelve thousand years ago; existed mainly in small, nomadic bands; and lived so lightly on the land that the Americas was, for all practical purposes, still a vast wilderness. But as Charles C. Mann now makes clear, archaeologists and anthropologists have spent the last thirty years proving these and many other long-held assumptions wrong.

In a book that startles and persuades, Mann reveals how a new generation of researchers equipped with novel scientific techniques came to previously unheard-of conclusions. Among them:

• In 1491 there were probably more people living in the Americas than in Europe.

• Certain cities–such as Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital–were far greater in population than any contemporary European city. Furthermore, Tenochtitlán, unlike any capital in Europe at that time, had running water, beautiful botanical gardens, and immaculately clean streets.

• The earliest cities in the Western Hemisphere were thriving before the Egyptians built the great pyramids.

• Pre-Columbian Indians in Mexico developed corn by a breeding process so sophisticated that the journal Science recently described it as “man’s first, and perhaps the greatest, feat of genetic engineering.”

• Amazonian Indians learned how to farm the rain forest without destroying it–a process scientists are studying today in the hope of regaining this lost knowledge.

• Native Americans transformed their land so completely that Europeans arrived in a hemisphere already massively “landscaped” by human beings.

Mannsheds clarifying light on the methods used to arrive at these new visions of the pre-Columbian Americas and how they have affected our understanding of our history and our thinking about the environment. His book is an exciting and learned account of scientific inquiry and revelation. https://www.penguinrandomhouseaudio.com/book/107178/1491/

MAANDAG, FEBRUARI 05, 2007

1491, Amerika voor Columbus

Zes maanden in de jungle. Zwemmen tussen de piranha’s, slangen en krokodillen, maar ook genieten van dolfijnen die geregeld langs komen in de Amazonerivier. Het idee dat je in een gebied bent wat niet is aangetast door de mens. Natuur die eindeloos lang ongerept in alle weelde heeft kunnen groeien en bloeien. Met recht oer-woud.

Tenminste dat dacht ik.

Woensdagavond was Charles Mann te gast in Wageningen. Prijswinnend schrijver van verschillende artikelen, coauteur van diverse boeken en nu ook zijn eigen boek “1491”. Een erg boeiende lezing waarin hij vertelde over de algemene aanname dat Amerika vrij laat bevolkt was en dat de invloed van deze indianen op het omliggende land vrij beperkt zou zijn. Een aanname die veel wordt gebruikt in de geschiedenislessen en een aanname die totaal verkeerd blijkt te zijn.

De grootte van de populatie indianen was groter dan eerder werd gedacht, wat de nodige gevolgen heeft gehad op de omgeving. Grote complexe steden, velden voor landbouw en verbindingswegen zouden het landschap hebben bepaald. Bijna geheel Amerika was gecultiveerd. Structuren die overigens nog steeds zijn terug te vinden, maar waar bijna niets over bekend is. Een blanco pagina in de geschiedenis, een nieuwe uitdaging voor archeologen.

Fascinerend dat er van zo’n grote menselijke impact, zo weinig bekend is. De overblijfselen zijn enorm, maar toch weten we er niks van af. Als kind wilde ik graag archeoloog worden. Tijdens dit verhaal kon ik me weer goed indenken waarom. http://ricksbooks.blogspot.com/2007/02/

In this groundbreaking work of science, history, and archaeology, Charles C. Mann radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus in 1492.

In the last twenty years, archeologists and anthropologists equipped with a battery of new scientific techniques have made far-reaching discoveries that have completely changed their understanding of what the Americas were like before Columbus’s arrival. Most of us learned in school that Indians crossed the Bering Strait 12,000 years ago, that they were few in number, and that they lived so lightly on the land that much of the Americas was essentially a wilderness. Most researchers now believe that every one of these statements is wrong. Indians were here far longer than previously believed, they lived in vastly greater numbers than had been thought, and they transformed the American landscape thoroughly. Not only has this fascinating new knowledge vastly altered our understanding of our history, it has enormous implications for today’s environmental disputes. Charles Mann illuminates all of these issues and reports on how these discoveries were made in this enthralling journey of scientific exploration.

Mann begins by showing how, beginning in the 1970s, researchers came to realize that the Indian population in 1491 must have been ten or twenty times higher than previously thought—there were more people in the Americas in 1491, the scientists came to believe, than in Europe; the Amazon delta may have been inhabited by more people in 1491 than it is now; cities including the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán were bigger than any city in Europe. And when European diseases swept through these societies, killing more than 90 percent of the people, it was the greatest demographic disaster in human history.

Mann shows how scientists learned that these much bigger societies were far more advanced than had been thought, and much older, as well. The Indian development of modern corn from a weed that looks nothing like it is still the most complex and far-reaching piece of genetic engineering ever performed. Indians clearly were traveling a different but equally sophisticated path as Europeans.

In 1491, Mann presents a riveting, compelling, eye-opening work of science.

“A superbly written and very important book: by far the most comprehensive synthesis I’ve ever seen of the growing body of evidence that our most deep-rooted ideas about the peopling of the Western hemisphere and the kinds of societies that had developed there by the time of European contact are fundamentally wrong. Charles C. Mann is one of those rare writers who can make scholarly concepts exciting and accessible without trivializing them. In 1491 he has integrated the latest research in many different areas with his own insights and experiences to produce a fascinating and addictively readable tour through the ‘New World’ before its ‘discovery.’ His book is, above all, a wonderful, unsentimental act of restitution—challenging centuries of cultural contempt and willful blindness to show just how vigorous, various, densely populated and profoundly human the pre-Columbian Americas really were.” —James Wilson, author of The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America

“We all know the first Americans wrote, built cities, and erected monuments, but they also changed the landscape. Well-informed in the ways of Aztec, Inca, Maya, Amazonian and Mound Builder, Mann engagingly reviews the social, environmental, and even the genetic conditions that set up the conquest that would follow the clash between two worlds—a clash not only among cultures but among ecosystems as well.” —Anthony Aveni, author of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico and Empires of Time, Russell B. Colgate Professor of Astronomy and Anthropology, Colgate University

“If you accept that there were tens of millions of people in the Americas in 1492, the common belief among the experts today, then you cannot reject what Charles Mann has to say. We all have been taught what the human species gained by the European invasion of the Americas. Now we have to consider what we, all of us, lost.” —Alfred W. Crosby, author of Ecological Imperialism and The Columbian Exchange, Professor Emeritus of Geography, American Studies and History, University of Texas

“This is a volume of unparrelleled historical and hemispheric sweep. Through a lively and comprehensive review, Mann brings together the most recent research from many fields to truly show us the New World in 1491—not a world of simple savages but rather one of thriving cities, states and empires, trade networks extending throughout the hemisphere, and landscapes everywhere shaped by native management. The civilizations of the Americas rivaled or exceeded those of Europe. This is the first volume that reveals the scope of the cultural loss created by the ‘great dying.’ A brilliant synthesis and sobering meditation on one of the planet’s great tragedies.” —Susanna Hecht, author of The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon, Professor of Urban Planning, Associate Director, School of Public Policy and Social Research, University of California at Los Angeles

“In his comprehensive new book, 1491, Charles Mann offers a comprehensive overview and an urgently needed update on the main archaeological and historical issues in the Americas before European arrival. From the Bering Strait to the Strait of Magellan, he brings forth the main academic controversies and presents them not merely as scholarly squabbles but as the issues that help shape the way we live in the modern world. In a lively and well written book, Charles Mann helps us to see the Americas in a new historical light.” —Jack Weatherford, author of Indian Givers and Genghis Khan and the Modern World, Professor of Anthropology, Macalester University

“Charles Mann takes us into a complex, fascinating and unknown world, that of the Indians who lived in this hemisphere before Columbus. He gently demolishes entrenched myths, with impressive scholarship, and with an elegance of style which makes his book a pleasure to read as well as a marvelous education.” —Howard Zinn

“In the tradition of Jared Diamond and John McPhee, a transforming new vision of pre-Columbian America.” —Richard Rhodes

“Every American knows it was a vast new world that Columbus found in 1492, and most imagine it was a thinly peopled paradise of plants, animals and hunter-gatherers waiting for civilization. The reality, Charles C. Mann tells us in his startling new book about the world before Columbus, is very different—two continents teeming with languages, cultures and mighty cities as big, as rich and even more populous than the capitals of Europe. But one thing the New World lacked—resistance to the diseases of the old. 1491 is lively and readable, filled with excitements and sorrows–a major contribution to our understanding of the achievements and the fate of the people we call Indians.” —Tom Powers

“When does American history begin? The old answer used to be 1492, with the European arrival in the Americas. That answer is no longer politically or historically correct. For the last thirty years or so historians, geographers and archaeologists have built up an arsenal of evidence about the residents of North America after the ice receded and before the Europeans arrived. Mann has mastered that scholarship and written the most elegant synthesis of the way we were before the European invasion.” —Joseph J. Ellis, author of His Excellency: George Washington

“Charles Mann has achieved the near impossible: distilling and reconciling the disparate ideas and findings of generations of scholars concerning the greatest collision of cultures ever, that of the Columbian Encounter. Written in a skillful, thoroughly enjoyable style that will please both the lay public and professional, this volume will immediately become a classic and the authoritative source on life in the Western Hemisphere before and immediately after 1491.” —Williams I. Woods, director of Environmental Studies, University of Kansas

“1491 is an eye-opening book that requires us to rethink virtually every assumption we have had about the Western Hemisphere before the arrival of Europeans. Charles Mann makes it clear that the notion of an ‘empty wilderness’ could not be further from the truth. 1491will change the way we think about wilderness and the ways humans have shaped the environment.” —Jan Dizard, Charles Hamilton Houston Professor of American Culture, Amherst College

“Engagingly written and utterly absorbing . . . part detective story, part epic and part tragedy.”—The Miami Herald

“Provocative . . . a Jared Diamond-like volley that challenges prevailing thinking about global development. Mann has chronicled an important shift in our vision of world development, one our young children could end up studying in their text books when they reach junior high.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“Marvelous . . . a revelation . . . our concept of pure wilderness untouched by grubby human hands must now be jettisoned.”—The New York Sun

“Monumental. . . . Mann slips in so many fresh, new interpretations of American history that it all adds up to a deeply subversive work.”—Salon

“Concise and brilliantly entertaining . . . reminiscent of John McPhee’s eloquence with scientific detail.”— The Los Angeles Times

“The bad news is that everything you were taught about the peopling and people of the Americas before Columbus is probably wrong. The good news is that the real story is bigger, grander and more fascinating than you ever imagined. Charles Mann, a meticulous researcher and captivating writer, has produced the most enthralling book I’ve ever read on the first Americans.” —Tim Cahill, author of Lost in My Own Backyard, Hold the Enlightenment and Jaguars Ripped My Flesh https://penguinrandomhousehighereducation.com/book/?isbn=9781400032051

New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

Charles C. Mann

Paperback edition 2006

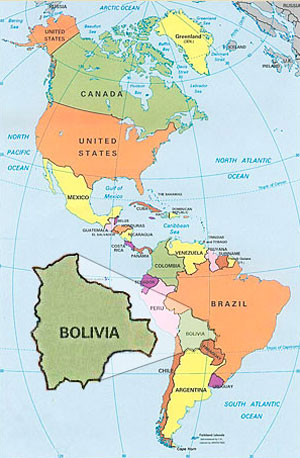

Imagine you’re on an airplane journey in the early eleventh century. It takes off from eastern Bolivia in South America and flies over the rest of the Western Hemisphere. What would you see from the windows?

Only fifty years ago, most historians would have predicted two continents of wilderness with scattered bands of people who were working their way toward civilization. This is wrong: new information seriously challenges accounts of the numbers of Indians and the length of time they had been living in the Western Hemisphere when Columbus arrived.

Consider one example. On the border with Brazil there is a nearly flat Bolivian province called the Beni, the size of Illinois and Indiana together. Scattered across the landscape are numberless island-like earthen mounds topped by forests and bridged by raised berms up to three miles long. Each mound is stabilized by broken pottery that is mixed into its earthen construction and rises as much as sixty feet above the flood plain, allowing trees to grow that cannot live in water.

Thirty years ago, the understanding was that Indians lived there in isolated groups and had so little impact on their environment that after millennia the continents remained mostly wilderness. Clark Erickson, an archaeologist, says this picture is mistaken in every respect: the landscape of the Beni was constructed by a populous, technologically advanced Indian society more than a thousand years ago. Much of the savannah of the Beni is natural, but there is evidence that the Indians trapped fish in the seasonally flooded grasslands by fashioning fish-corralling fences among the causeways. The grasslands were maintained and expanded by regularly setting fire to large parts of them, which is still done today to maintain the savannah for cattle.

The Beni was a very important center of a pre-Columbian civilization known as the hydraulic culture of Las Lomas (the hills), a culture that constructed over 20,000 man-made artificial hills, all interconnected by thousands of square kilometers of aqueducts, channels, embankments, artificial lakes and lagoons as well as terraces.

The Siriono are the best known of a number of Native American groups in the Beni today. Between 1940 and 1942 a young doctoral student in anthropology named Allan R. Holmberg lived among them, and published an account in 1950 of his experience in Nomads of the Long Bow. Holmberg reported that the Siriono lived with want and hunger and could neither count nor make fire and seemed to practice no religion except for an uncrystallized conception of the universe. He saw them as primitive humankind living in a raw state of nature that for millennia had existed almost without change. Quickly recognized as a classic, the book provided an enduring image of South American Indians to the outside world.

Holmberg was mistaken.

Researchers, in the 1990s, learned that the Siriono were indeed a desperately impoverished people but for different reasons. They had arrived in the Beni as late as the seventeenth century, and their population had been at least three thousand. By the time Holmberg encountered them, less than 150 people had survived the smallpox and influenza that had destroyed their villages in the 1920s. As the epidemics hit them they were also fighting the white cattle ranchers who were taking over the region, and the Bolivian government aided the ranchers by hunting down the Siriono. The wandering people that Holmberg had traveled with in the forest were actually the persecuted survivors.

Missionaries and conquistadors brought the idea back to Spain and Europe that Native Americans lived passively with little to no effect on their environment. Over time various forms of this stereotype were embraced both by those who hated Indians and those who admired them.

It was only when new tools and disciplines, such as demography, climatology, carbon-14 dating and ice-core sampling, satellite photography, soil assays, and genetic microsatellite analysis were employed that the idea that the indigenous occupants of one-third of the earth’s surface had changed their environment so little over thousands of years began to look implausible.

And our misunderstanding of Bolivia is but one part of our mistake about what America was like in 1492. After Columbus sailed into the Western Hemisphere and traders and colonists soon followed, a phenomenon called ecological release occurred. Throughout the hemisphere ecosystems faltered. Colonists in Jamestown complained about the scourge of rats they had accidentally imported. Tame European clover and blue grass transformed themselves and swept through areas so quickly that the first English colonists in Kentucky found both species waiting for them. And peaches in the southeast that previously had not grown in the wild proliferated so much that eighteenth-century farmers feared the Carolinas would become a wilderness of peach trees!

South America was hit especially hard. Spinach and endive, escaping from colonial gardens, grew into impassable, six-foot thickets on the Peruvian coast, and mint took over the valleys higher up in the Andes. In the pampas of Argentina and Uruguay, the voyager Charles Darwin saw hundreds of square miles choked by feral artichoke and found that peach wood had become the main supply of firewood in Buenos Aires. Some invasions canceled each other out, for example, the plague of endive in Peru may have been checked by a simultaneous plague of rats that overran the land and destroyed crops.

Maize was farmed for thousands of years in irrigated and carefully regulated terraces.

Until Columbus, Indians were a keystone species in most of the hemisphere. They annually burned undergrowth, cleared and replanted forests, built canals and raised fields, hunted bison and netted salmon, and grew maize and manioc. Native Americans had been managing their environments for thousands of years. By and large, they modified their landscapes in stable and intelligent ways.

Some areas of maize have been farmed for thousands of years. In Peru, for instance, where irrigated terraces of crops covered huge areas, wholesale transformations were carried out in an exceptional way. All of these efforts required close and continual oversight, but in the sixteenth century, epidemics removed the checks and balances. After 1492 American landscapes were emptied of Native Americans, which deregulated the ecosystems. The forests that the first New England colonists thought were primeval and enduring were actually in the midst of violent change and demographic collapse.

Archeologists think there were not large numbers of passenger pigeons before Columbus.

In 1823 the artist and naturalist, John Audubon saw a flock of passenger pigeons passing overhead in a single cloud for three whole days, obscuring the light of noon-day as if by an eclipse. In Audubon’s day one out of every four birds was a passenger pigeon. And suddenly, the passenger pigeon vanished with the last bird dying in September 1914.

Given that the passenger pigeon was a competitor of the Indians for mast (various nuts) as well as berries, and because crowds of pigeons would eat the food in their fields, it was expected that Indians would hunt them as enthusiastically as they did turkey, deer, and raccoons that also ate from their fields. Judging by the bones in archaeological sites, however, the Indians were enthusiastic hunters of everything except passenger pigeons, which leads archaeologists to think that there were not large numbers of these pigeons before Columbus. The impact of European contact altered the ecological dynamics in such a way that the passenger pigeon increased. The avian throngs that Audubon saw were out-break populations—always a symptom of an extraordinarily disrupted ecological system.

Sugar Loaf Mound, above, is one of a group of mounds that were constructed by Native Americans that lived in the St. Louis area from about 600–1300 CE.

These are but a few examples. By the time Columbus arrived, the Western Hemisphere had been thoroughly touched by human hands. Agriculture occurred in as much as two-thirds of what is now the United States, with large areas of the southwest terraced and irrigated. Among the maize fields in the Midwest and Southeast, mounds by the thousands were visible. The forests of the eastern seaboard had been moved back from the coasts and were now lined with farms. Salmon nets stretched across every ocean-bound stream in the northwest. And almost everywhere there was evidence that the Indians had set fires.

South of the Rio Grande, Indians had converted the Mexican basin and Yucatan into artificial environments. Terraces and canals and stony highways lined the western face of the Andes. Raised fields and causeways covered the Beni. Agriculture reached into Argentina and central Chile. Indians had converted perhaps a quarter of the Amazon forest into farms and agricultural forests and changed the once-forested Andes to grass and brush. The Inca, worried about fuel supply, were planting tree farms.

All of this development had implications for animal populations. For example, as settlements grew so did their maize fields. Indians discouraged animals, large and small, from their fields by hunting them until they were scarce around their homes. At the same time, they tried to encourage the larger animals to grow in number further away, where they would be useful. When disease swept Indians from the land, the entire ecological regime they established collapsed.

In the early sixteenth century, Hernando de Soto’s expedition through the Southeast saw hordes of people, but apparently not bison, or he would have mentioned it. More than a century later the French explorer La Salle canoed down the Mississippi River. Where de Soto had found prosperous cities, La Salle encountered solitude without any trace of humans, but he saw bison everywhere, grazing in herds on the great prairies that then bordered the Mississippi. When Indians died, these huge creatures vastly extended their range and numbers. According to scientists, the massive, thundering herds were a pathological symptom, something the land had not seen before and is unlikely to see again.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the hemisphere was thick with artificial wilderness. Far from destroying a pristine wilderness, Europeans seem to have created it. The newly emptied wilderness was indeed beautiful, but it was a product of demographic calamity.

Map showing the course of the expeditions of Hernando de Soto and Robert de La Salle. Where de Soto had found prosperous cities, a century later La Salle encountered no people, only bison.

About the Author: Charles C. Mann is a correspondent for Science and The Atlantic Monthly, and has co-written four previous books including Noah’s Choice: The Future of Endangered Species and The Second Creation. A three-time National Magazine Award finalist, he has won awards from the American Bar Association, the Margaret Sanger Foundation, the American Institute of Physics, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, among others. His writing was selected for The Best American Science Writing 2003 and The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2003.

Tarih & Kuram Yayınevi published Charles C. Mann’s “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” and “1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created”

Tarih & Kuram Yayınevi published Charles C. Mann’s “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” and “1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created” with translations of Cedet Çiner and Kadriye Göksel.

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus :

In this groundbreaking work of science, history, and archaeology, Charles C. Mann radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus in 1492.

Contrary to what so many Americans learn in school, the pre-Columbian Indians were not sparsely settled in a pristine wilderness; rather, there were huge numbers of Indians who actively molded and influenced the land around them. The astonishing Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had running water and immaculately clean streets, and was larger than any contemporary European city. Mexican cultures created corn in a specialized breeding process that it has been called man’s first feat of genetic engineering. Indeed, Indians were not living lightly on the land but were landscaping and manipulating their world in ways that we are only now beginning to understand. Challenging and surprising, this a transformative new look at a rich and fascinating world we only thought we knew.

1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created :

From the author of 1491—the best-selling study of the pre-Columbian Americas—a deeply engaging new history of the most momentous biological event since the death of the dinosaurs.

More than 200 million years ago, geological forces split apart the continents. Isolated from each other, the two halves of the world developed radically different suites of plants and animals. When Christopher Columbus set foot in the Americas, he ended that separation at a stroke. Driven by the economic goal of establishing trade with China, he accidentally set off an ecological convulsion as European vessels carried thousands of species to new homes across the oceans.

The Columbian Exchange, as researchers call it, is the reason there are tomatoes in Italy, oranges in Florida, chocolates in Switzerland, and chili peppers in Thailand. More important, creatures the colonists knew nothing about hitched along for the ride. Earthworms, mosquitoes, and cockroaches; honeybees, dandelions, and African grasses; bacteria, fungi, and viruses; rats of every description—all of them rushed like eager tourists into lands that had never seen their like before, changing lives and landscapes across the planet.

Eight decades after Columbus, a Spaniard named Legazpi succeeded where Columbus had failed. He sailed west to establish continual trade with China, then the richest, most powerful country in the world. In Manila, a city Legazpi founded, silver from the Americas, mined by African and Indian slaves, was sold to Asians in return for silk for Europeans. It was the first time that goods and people from every corner of the globe were connected in a single worldwide exchange. Much as Columbus created a new world biologically, Legazpi and the Spanish empire he served created a new world economically.

As Charles C. Mann shows, the Columbian Exchange underlies much of subsequent human history. Presenting the latest research by ecologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians, Mann shows how the creation of this worldwide network of ecological and economic exchange fostered the rise of Europe, devastated imperial China, convulsed Africa, and for two centuries made Mexico City—where Asia, Europe, and the new frontier of the Americas dynamically interacted—the center of the world. In such encounters, he uncovers the germ of today’s fiercest political disputes, from immigration to trade policy to culture wars.

In 1493, Charles Mann gives us an eye-opening scientific interpretation of our past, unequaled in its authority and fascination.

28 August 2019 http://www.onkagency.com/1491-1493-tarih-ve-kuram-yayinevi/

Charles C. Mann:

THE PROBLEM WITH environmentalists, Lynn Margulis used to say, is that they think conservation has something to do with biological reality. A researcher who specialized in cells and microorganisms, Margulis was one of the most important biologists in the last half century—she literally helped to reorder the tree of life, convincing her colleagues that it did not consist of two kingdoms (plants and animals), but five or even six (plants, animals, fungi, protists, and two types of bacteria).

Until Margulis’s death last year, she lived in my town, and I would bump into her on the street from time to time. She knew I was interested in ecology, and she liked to needle me. Hey, Charles, she would call out, are you still all worked up about protecting endangered species?

Margulis was no apologist for unthinking destruction. Still, she couldn’t help regarding conservationists’ preoccupation with the fate of birds, mammals, and plants as evidence of their ignorance about the greatest source of evolutionary creativity: the microworld of bacteria, fungi, and protists. More than 90 percent of the living matter on earth consists of microorganisms and viruses, she liked to point out. Heck, the number of bacterial cells in our body is ten times more than the number of human cells!

Bacteria and protists can do things undreamed of by clumsy mammals like us: form giant supercolonies, reproduce either asexually or by swapping genes with others, routinely incorporate DNA from entirely unrelated species, merge into symbiotic beings—the list is as endless as it is amazing. Microorganisms have changed the face of the earth, crumbling stone and even giving rise to the oxygen we breathe. Compared to this power and diversity, Margulis liked to tell me, pandas and polar bears were biological epiphenomena—interesting and fun, perhaps, but not actually significant.

Does that apply to human beings, too? I once asked her, feeling like someone whining to Copernicus about why he couldn’t move the earth a little closer to the center of the universe. Aren’t we special at all?

This was just chitchat on the street, so I didn’t write anything down. But as I recall it, she answered that Homo sapiens actually might be interesting—for a mammal, anyway. For one thing, she said, we’re unusually successful.

Seeing my face brighten, she added: Of course, the fate of every successful species is to wipe itself out.

OF LICE AND MEN….. https://solutions.synearth.net/2012/11/working-together-1134/

As civilizações perdidas da Amazônia e a evangelização dos indígenas

Após 10 anos de pesquisas, arqueológicas no Alto Xingu, cientistas do Brasil e dos EUA constataram que, antes de Colombo, os índios da região moravam em conglomerados comparáveis a algumas cidades da Grécia ou da Idade Média.

Há 2.000 anos, essas cidades de até 50 hectares eram dotadas de muros, praças e centros cerimoniais, e estavam ligadas por uma densa rede de estradas.

Seus habitantes desmatavam, construíam canais, tinham roças, pomares, tanques para criar tartarugas, pescavam em larga escala e faziam uso contínuo e sistemático da terra.

As conclusões desses trabalhos foram sendo publicadas numasérie de artigosda reputada “Science”, revista da Associação Americana para o Progresso da Ciência (American Association for the Advancement of Science ‒ AAAS).

Na região amazônica de Beni, Bolívia, arqueólogos haviam observado de avião o traçado muito bem definido de canalizações e divisórias de roças, bem como a existência de intrigantes “terras negras”, que só podiam provir da adubação.

Os trabalhos tiveram dificuldades para avançar devido à hostilidade dos ambientalistas.

Para o escritor científico Charles C. Mann, autor de “1491”, obra que ganhou o prêmio da U.S. National Academy of Sciences para o melhor livro do ano (2005), os ambientalistas temiam que o trabalho científico trouxesse um desmentido ao “prístino mito”.

Segundo esse mito ideológico e teológico, antes da descoberta e evangelização de América, os índios viviam num relacionamento edênico com a selva amazônica.

Pertencendo eles, porém, ao gênero humano, é natural que fizessem o que os homens fazem e sempre fizeram: construir casas, cidades e estradas, plantar, criar animais para se alimentar, tecer para se vestir e acumular para garantir o sustento de seus filhos.

Muitas das observações dos cientistas já haviam sido parcialmente publicadas, e as fotos podem se obter na Internet.

O antropólogo Carlos Fausto e a linguista Bruna Franchetto, ambos do Museu Nacional, estiveram entre os pesquisadores no Alto Xingu; como também o arqueólogo americano Michael Heckenberger, da Universidade da Flórida, autor principal do estudo.

Para Heckenberger, o planejamento urbano amazônico pré-Colombo era mais complicado que o da Europa medieval, e incluía, segundo Fausto, “uma distribuição geométrica precisa”.

| A diferença dos tons de verde patenteia a adubação das terras em tempos remotos |

Ficou assim comprovado que a Amazônia pré-colombiana viu florescer remarcáveis concentrações urbanas.

Na plenitude de sua expansão, a civilização do Xingu incluía 50 mil habitantes, dotados de autoridades políticas e religiosas que governavam as cidades menores a partir das principais.

Algumas de suas estradas – que podiam ter entre 20 e 50 metros de largura – foram identificadas como tendo cinco quilômetros de extensão. Para atravessar alagamentos foram construídas pontes, elevações de terreno e canais para canoas.

Também foram erigidas barragens que formavam lagos artificiais, sinais que mostram o grau de civilização daquele conjunto humano.

Os pesquisadores detectaram perto de 15 grupos principais de aldeias, espalhados numa superfície de dois milhões de hectares.

As tradições orais dos índios kuikuro – habitantes da região que, segundo Fausto, “têm um nome para cada uma das aldeias” – orientaram as pesquisas e foram confirmadas pelos achados. Existiram, portanto, civilizações política, religiosa, econômica e culturalmente definidas.

O arqueólogo Heckenberger sublinha que aquilo que até agora se supunha ser “uma floresta tropical virgem”, de fato é uma região altamente influenciada pela ação humana.

Segundo o arqueólogo, o planejamento urbano amazônico pré-histórico era mais complicado que o da Europa medieval. “Lá você tinha a “town” [vila] e a “hinterland” [zona rural] sem integração. Aqui estava tudo junto”, diz.

“A organização espacial xinguana também denota uma hierarquia política entre vilas que remete às cidades-estado gregas. Cada “aglomerado galáctico” era um centro independente de poder, que provavelmente mantinha relações com outros aglomerados.

“Você não encontra uma capital da região”, diz Carlos Fausto. “O maior nível de organização é a vila cerimonial”.

Embora o escopo dos trabalhos no Alto Xingu e no Beni fosse apenas científico, eles acabaram por mostrar que o mito de uma floresta intocada é um sonho ideológico anti-histórico.

Uma propaganda da qual o ambientalismo e o comuno-tribalismo são useiros e vezeiros quer fazer crer que o próprio da cultura dos índios da Amazônia é de viverem como selvagens, vagando nus pelo mato e incapazes por natureza de constituir uma civilização.

Segundo tal propaganda, essa forma de vida selvagem seria uma fase da evolução do macaco ao homem.

E, mais ainda, os civilizados teríamos sido “desviados” da evolução “boa” pela civilização.

Agora se pode, a partir de dados científicos, sustentar com tranquilidade que a lamentável situação em que vivem certos índios não é decorrente de uma fatalidade cultural imposta pela “evolução”, mas sim uma decadência de povos que tiveram uma cultura mais alta.

Obviamente, esta constatação é um convite para ajudar esses índios a se recuperarem, inclusive do ponto de vista civilizatório.

As descobertas patenteiam um princípio que sempre orientou a obra missionária da Igreja: embora pagãos e decaídos, os índios são seres humanos beneficiados pelos frutos infinitos da Redenção conquistados por Nosso Senhor Jesus Cristo no alto da Cruz.

Assim, também a eles se aplica o mandamento evangélico: “Ide e evangelizai todos os povos”.

É portanto injusto e anticristão atribuir-lhes uma condição de entes integrados na floresta, privados de entrar em contato com a civilização, de progredir e receber a pregação da Palavra de Deus; em suma, de se tornarem parte da grei abençoada da Santa Igreja Católica.

Eles têm alma e estão chamados a serem filhos de Deus, a conhecerem a Igreja, a receber a graça divina e conquistar a vida eterna!

Se outra prova fosse necessária, os referidos achados arqueológicos apontam-nos como provenientes de um elevado estágio civilizatório que defeitos e/ou vícios morais rebaixaram até o lamentável estado em que se encontram.

Porém, nada disso pode ser empecilho para levar até eles as palavras de salvação da Igreja, a graça do batismo e os sacramentos, sinais sensíveis da graça divina.

E, junto com a vida sobrenatural, os tesouros culturais da Civilização Cristã.

As descobertas no Alto Xigu constituem assim mais um estímulo caritativo à obra de evangelização dos indígenas. Evangelização que é ponto de partida natural para uma cultura genuinamente cristã e brasileira.

Os silvícolas serão destarte beneficiados com a plenitude de bens hauridos pelos filhos de Deus na Santa Igreja Católica em decorrência da prática de seus santos e salutares ensinamentos.

Fonte: cienciaconfirmaigreja.blogspot.com.br

FEVEREIRO 10, 2017

Nenhum comentário

Cientistas encontram na Amazônia vestígios de povos de mais de 2.000 anos

Muito antes de os europeus terem chegado às Américas em 1492, a floresta amazônica foi transformada durante milhares de anos pelos povos indígenas, que escavaram mais de 400 círculos misteriosos na paisagem acriana – informaram cientistas nesta segunda-feira (6).

Embora o propósito dessas centenas de valetas, ou geoglifos, permaneçam um mistério, cientistas afirmam que podem ter servido como locais de ritual.

Juntamente com fotos aéreas, o desmatamento moderno ajudou a revelar cerca de 450 desses desenhos no estado do Acre, oeste da Amazônia brasileira.

“O fato de esses locais terem ficado escondidos sob a floresta tropical madura realmente muda a ideia de que as florestas amazônicas são ‘ecossistemas intocados’”, afirmou a principal autora do estudo, Jennifer Watling, pesquisadora de Pós-Doutorado do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnografia na USP (Universidade de São Paulo).

Arqueólogos descobriram pouquíssimos artefatos dos locais e cientistas suspeitam que as estruturas – que se estendem por 13.000 quilômetros quadrados – não foram construídas para criar cidades, ou por razões de defesa.

Ao invés disso, eles acreditam que os humanos alteraram florestas de bambu e criaram clareiras pequenas e temporárias, “concentrando-se em espécies de árvores economicamente valiosas, como palmeiras, criando uma espécie de ‘supermercado pré-histórico’ de úteis produtos florestais”, destacou o estudo publicado na publicação científica americana Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

O estudo se baseou em técnicas inovadoras usadas para reconstruir cerca de 6.000 anos de histórico da vegetação e de fogo ao redor de dois sítios, contendo geoglifos.

Watling, que realizou a pesquisa enquanto estudava na Universidade de Exeter, na Grã-Bretanha, disse que as descobertas mostram que a região não foi intocada pelos humanos no passado, contrariando a crença popular.

“Nossa evidência de que as florestas amazônicas foram manejadas por povos indígenas muito antes do contato com os europeus não deveria ser usada como justificativa para as formas destrutivas e insustentáveis de uso do solo praticadas hoje”, acrescentou.

“Deveria, ao contrário, servir para destacar a ingenuidade dos regimes de subsistência no passado que não levam à degradação florestal e a importância dos povos indígenas na descoberta de alternativas mais sustentáveis para o uso do solo”, concluiu.

Brasil tem registro humano mais antigo

A arqueologia brasileira é vasta em achados, com exemplares de fósseis de mais dez mil anos. Os vestígios de registro humano mais antigos foram encontrados no Parque Nacional da Serra da Capivara, localizado no Piauí, a 510 km de Teresina. O local reúne pinturas rupestres de milhares de anos. Restos de fogueiras podem ser os mais antigos da América. http://hayah.com.br/tag/amazonia/

Fonte:uol.com.br

This spring, discover the incredible true story of THE LOST CITY OF Z, based on the bestselling book by David Grann. Directed by James Gray, starring Charlie Hunnam, Robert Pattinson, Sienna Miller, and Tom Holland. » SUBSCRIBE: http://bit.ly/AmazonStudiosSubscribe » Now in Select Theaters! » Check out more The Lost City of Z: http://bit.ly/AmazonTheLostCityofZ About The Lost City of Z: Based on author David Grann’s nonfiction bestseller, THE LOST CITY OF Z tells the incredible true story of British explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam), who journeys into the Amazon at the dawn of the 20th century and discovers evidence of a previously unknown, advanced civilization that may have once inhabited the region. Despite being ridiculed by the scientific establishment who regard indigenous populations as “savages,” the determined Fawcett – supported by his devoted wife (Sienna Miller), son (Tom Holland) and aide de camp (Robert Pattinson) – returns time and again to his beloved jungle in an attempt to prove his case, culminating in his mysterious disappearance in 1925. An epically-scaled tale of courage and obsession, told in Gray’s classic filmmaking style, THE LOST CITY OF Z is a stirring tribute to the exploratory spirit and those individuals driven to achieve greatness at any cost.

The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon is the debut non-fiction book by American author David Grann. The book was published in 2009 and recounts the activities of the British explorer Percy Fawcett who, in 1925, disappeared with his son in the Amazon while looking for an ancient lost city. For decades explorers and scientists have tried to find evidence of his party and of the “Lost City of Z“.

Grann also recounts his own journey into the Amazon, by which he discovered new evidence about how Fawcett may have died. He learned that Fawcett may have come upon “Z” without knowing it.[1] The book claims as many as 100 people may have died or disappeared (and are presumed dead) searching for Fawcett over the years; however, the more historically accurate toll, according to John Hemming, is one.[2] The Lost City of Z was the basis of a 2016 feature film of the same name, written and directed by James Gray. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lost_City_of_Z_(book)

David Grann — Charlie Rose

https://charlierose.com/videos/30603

” 1491:NEW REVELATIONS OF THE AMERICAS BEFORE COLUMBUS ” PART 1

https://www.academia.edu/27784634/_1491_NEW_REVELATIONS_OF_THE_AMERICAS_BEFORE_COLUMBUS_PART_1