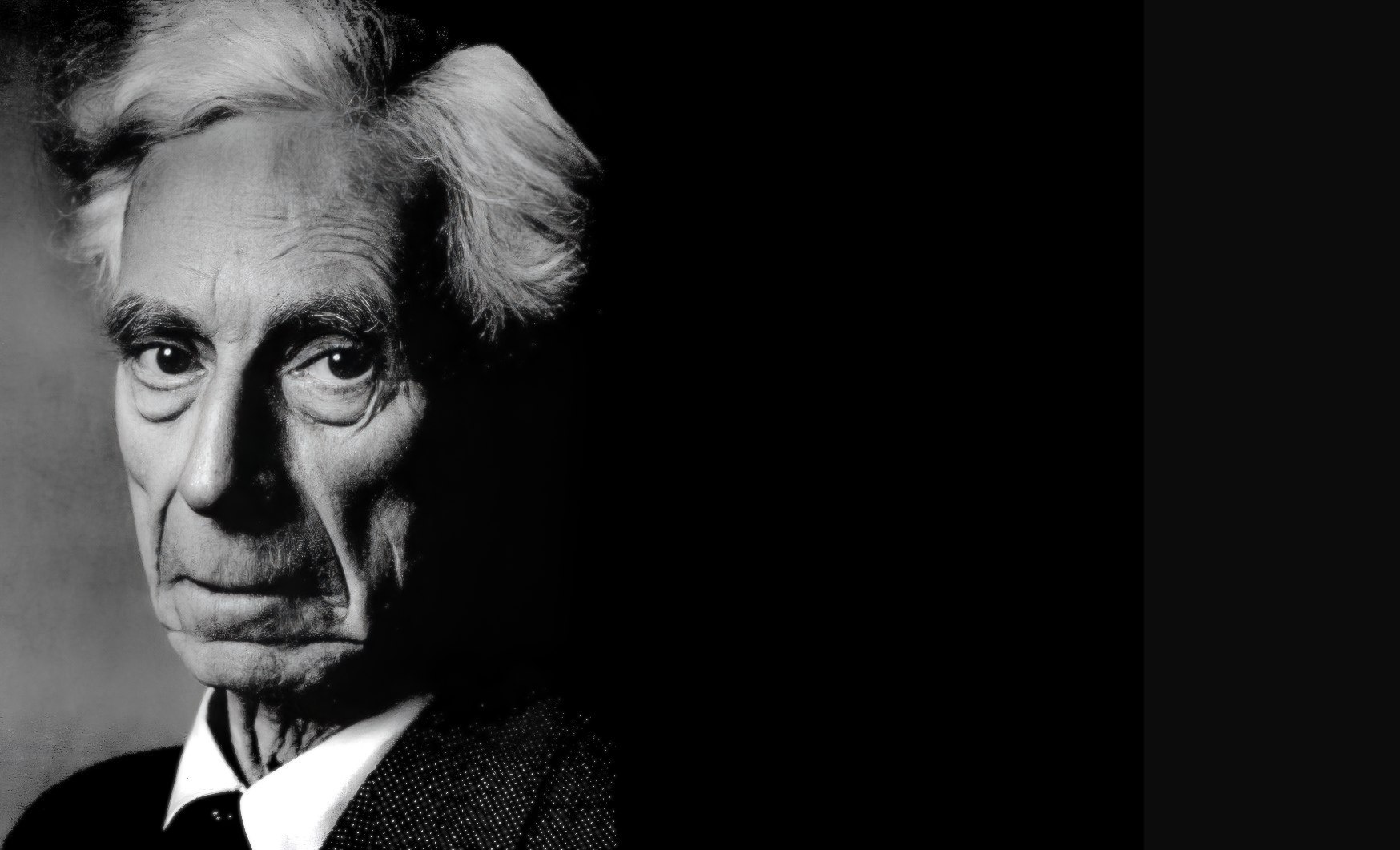

What is Time? Is Time subjective? Bertrand Russell was impressed, but was not in full agreement, with St. Augustine’s philosophy of time – the view that time is subjective and closely linked to memory.

“For the most part, he [Saint Augustine] does not occupy himself with pure philosophy, only theology, but when he does he shows very great ability … As a philosopher, therefore, Augustine deserves a high place … This leads Saint Augustine to a very admirable relativistic theory of time.”

“Saint Augustine suggests that time is subjective: time is in the human mind, which expects, considers, and remembers. It follows that there can be no time without a created being, and that to speak of time before the Creation is meaningless. I do not myself agree with this theory, in so far as it makes time something mental. But it is clearly a very able theory, deserving to be seriously considered. I should go further, and say that it is a great advance on anything to be found on the subject in Greek philosophy. It contains a better and clearer statement than Kant’s of the subjective theory of time–a theory which, since Kant, has been widely accepted among philosophers.”

━━

Background: Philosophy of space and time focuses on a number of basic issues, including whether time and space exist independently of the mind, whether they exist independently of one another, what accounts for time’s apparently unidirectional flow, whether times other than the present moment exist, and questions about the nature of identity (particularly the nature of identity over time).

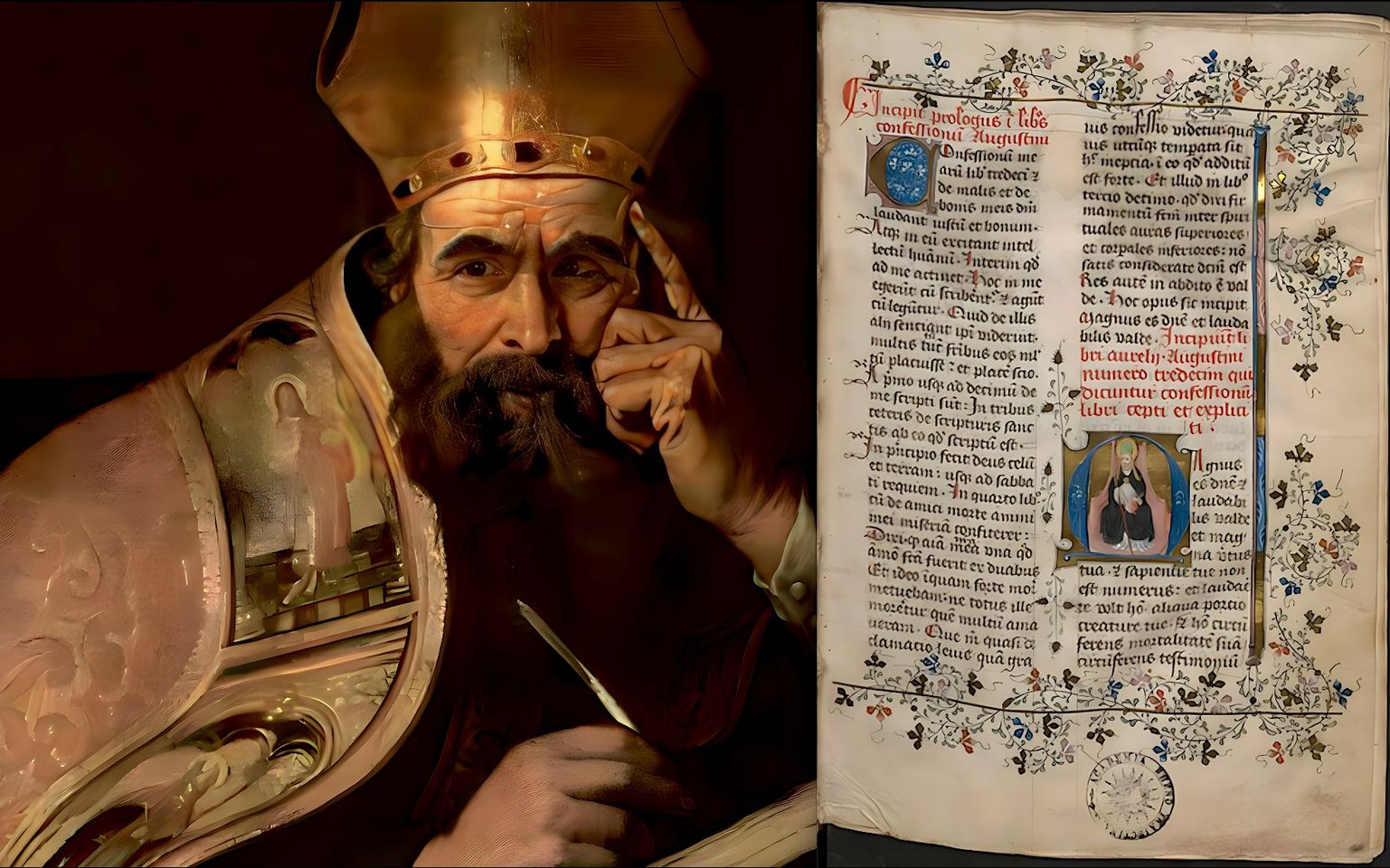

Augustine’s philosophical method, especially demonstrated in his late Roman Empire autobiographical work Confessions (AD 397 and 400), had a continuing influence on both Continental and Analytic philosophy throughout the 20th century. His descriptive approach to intentionality, memory, and language as these phenomena are experienced within consciousness and time anticipated and inspired the insights of modern phenomenology and hermeneutics.

Martin Heidegger refers to Augustine’s descriptive philosophy at several junctures in his influential work Being and Time and Ludwig Wittgenstein extensively quotes Augustine in Philosophical Investigations for his approach to language, both admiringly, and as a sparring partner to develop his own ideas, including an extensive opening passage from the Confessions.

Until Albert Einstein‘s reinterpretation of the physical concepts associated with time and space in 1907, time was considered to be the same everywhere in the universe, with all observers measuring the same time interval for any event. Einstein, in his special theory of relativity, postulated the constancy and finiteness of the speed of light for all observers. He showed that this postulate, together with a reasonable definition for what it means for two events to be simultaneous, requires that distances appear compressed and time intervals appear lengthened for events associated with objects in motion relative to an inertial observer.

━━

Bertrand Russell‘s full commentary of Augustine’s thoughts concerning the philosophy of time excerpt A History of Western Philosophy (1945):

“SAINT AUGUSTINE was a very voluminous writer, mainly on theological subjects. Some of his controversial writing was topical, and lost interest through its very success; but some of it remained practically influential down to modern times. For the most part, he does not occupy himself with pure philosophy, only theology, but when he does he shows very great ability …

Why was the world not created sooner? Because there was no “sooner”. Time was created when the world was created. God is eternal, in the sense of being timeless; in God there is no before and after, but only an eternal present. God’s eternity is exempt from the relation of time; all time is present to Him at once. He did not precede His own creation of time, for that would imply that He was in time, whereas He stands eternally outside the stream of time.

This leads Saint Augustine to a very admirable relativistic theory of time.

“What, then, is time?” he asks. “If no one asks of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not.” Various difficulties perplex him. Neither past nor future, he says, but only the present, really is; the present is only a moment, and time can only be measured while it is passing. Nevertheless, there really is time past and future. We seem here to be led into contradictions. The only way Augustine can find to avoid these contradictions is to say that past and future can only be thought of as present: “past” must be identified with memory, and “future” with expectation, memory and expectation being both present facts. There are, he says, three times: “a present of things past, a present of things present, and a present of things future.” “The present of things past is memory; the present of things present is sight; and the present of things future is expectation.” To say that there are three times, past, present, and future, is a loose way of speaking.

He realizes that he has not really solved all difficulties by this theory. “My soul yearns to know this most entangled enigma,” he says, and he prays to God to enlighten him, assuring Him that his interest in the problem does not arise from vain curiosity. “I confess to Thee, O Lord, that I am as yet ignorant what time is.” But the gist of the solution he suggests is that time is subjective: time is in the human mind, which expects, considers, and remembers. It follows that there can be no time without a created being, and that to speak of time before the Creation is meaningless.

I do not myself agree with this theory, in so far as it makes time something mental. But it is clearly a very able theory, deserving to be seriously considered. I should go further, and say that it is a great advance on anything to be found on the subject in Greek philosophy. It contains a better and clearer statement than Kant’s of the subjective theory of time–a theory which, since Kant, has been widely accepted among philosophers.

The theory that time is only an aspect of our thoughts is one of the most extreme forms of that subjectivism which, as we have seen, gradually increased in antiquity from the time of Protagoras and Socrates onwards. Its emotional aspect is obsession with sin, which came later than its intellectual aspects. Saint Augustine exhibits both kinds of subjectivism. Subjectivism led him to anticipate not only Kant’s theory of time, but Descartes’ cogito. In his Soliloquia he says: “You, who wish to know, do you know you are? I know it. Whence are you? I know not. Do you feel yourself single or multiple? I know not. Do you feel yourself moved? I know not. Do you know that you think? I do.” This contains not only Descartes’ cogito, but his reply to Gassendi’s ambulo ergo sum. As a philosopher, therefore, Augustine deserves a high place.”

― Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (1945), Book Two. Catholic Philosophy, Part. I. The Fathers, Ch. IV: Saint Augustine’s Theology and Philosophy, pp. 352-55

━━

Image left: The Four Doctors of the Western Church Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), detail oil on canvass Gerard Seghers between 1600-50, Kingston Lacy Collection.

Image right: Confessiones. Manuscript on vellum. Germany, first half 13th century.

Augustine of Hippo (Latin: Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings influenced both the development of Western philosophy and Western Christianity, and he is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers of the Latin Church in the Patristic Period. His many important works include The City of God, On Christian Doctrine, and the more philosophical Confessions.