Philip David Charles (Phil) Collins (Chiswick (Londen), 30 januari 1951) is een Brits popmuzikant. Hij werd bekend als drummer en leadzanger van de progressieve-rockband Genesis, won als soloartiest verscheidene Grammy‘s en een Academy Award en heeft eveneens een succesvolle carrière als acteur.

Zijn singles, die vaak over verloren liefdes gaan, varieerden van het met drums beladen In the Air Tonight, tot het dance–popnummer Sussudio en de politieke opvattingen van zijn succesvolle nummer Another Day in Paradise. Zijn internationale populariteit veranderde Genesis van een progressieve-rockband met een relatief kleine groep fans tot een van de grootste rockbands aller tijden met een vertrouwde naam binnen de hitlijsten.

Bij Genesis begon hij in eerste instantie alleen met drummen en was hij achtergrondzanger voor leadzanger Peter Gabriel. Pas in 1975, toen Gabriel de band verliet, werd Collins hoofdzanger van Genesis. Tegen het einde van de jaren zeventig was met de hit Follow You Follow Me de drastische verandering ten opzichte van de vroege jaren duidelijk en bleek dat de band goed zonder Gabriel kon. Zijn solocarrière, die flink beïnvloed is door zijn privéleven, brachten hem en Genesis tot een commercieel succes. Volgens Atlantic Records was Collins’ totale wereldwijde afzet als een soloartiest in 2002 meer dan 100 miljoen albums. Dat maakt Collins met Michael Jackson en Paul McCartney de enige artiesten, die zowel met een band als solo meer dan 100 miljoen albums hebben verkocht.

Collins werkte met veel artiesten samen, onder wie The Four Tops, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Robert Plant, Eric Clapton, Frida (ABBA), Mike Oldfield, Sting, Brian Eno, Peter Gabriel, Led Zeppelin, Ozzy Osbourne, Queen, Laura Pausini, Lil’ Kim, Philip Bailey, John Martyn en The Who.

Philip David Charles (Phil) Collins (Chiswick (Londen), 30 januari 1951) is een Brits popmuzikant. Hij werd bekend als drummer en leadzanger van de progressieve-rockband Genesis, won als soloartiest verscheidene Grammy‘s en een Academy Award en heeft eveneens een succesvolle carrière als acteur.

Zijn singles, die vaak over verloren liefdes gaan, varieerden van het met drums beladen In the Air Tonight, tot het dance–popnummer Sussudio en de politieke opvattingen van zijn succesvolle nummer Another Day in Paradise. Zijn internationale populariteit veranderde Genesis van een progressieve-rockband met een relatief kleine groep fans tot een van de grootste rockbands aller tijden met een vertrouwde naam binnen de hitlijsten.

Bij Genesis begon hij in eerste instantie alleen met drummen en was hij achtergrondzanger voor leadzanger Peter Gabriel. Pas in 1975, toen Gabriel de band verliet, werd Collins hoofdzanger van Genesis. Tegen het einde van de jaren zeventig was met de hit Follow You Follow Me de drastische verandering ten opzichte van de vroege jaren duidelijk en bleek dat de band goed zonder Gabriel kon. Zijn solocarrière, die flink beïnvloed is door zijn privéleven, brachten hem en Genesis tot een commercieel succes. Volgens Atlantic Records was Collins’ totale wereldwijde afzet als een soloartiest in 2002 meer dan 100 miljoen albums. Dat maakt Collins met Michael Jackson en Paul McCartney de enige artiesten, die zowel met een band als solo meer dan 100 miljoen albums hebben verkocht.

Collins werkte met veel artiesten samen, onder wie The Four Tops, George Harrison, Paul McCartney, Robert Plant, Eric Clapton, Frida (ABBA), Mike Oldfield, Sting, Brian Eno, Peter Gabriel, Led Zeppelin, Ozzy Osbourne, Queen, Laura Pausini, Lil’ Kim, Philip Bailey, John Martyn en The Who.

In 1970 beantwoordde de 19-jarige Collins een advertentie in het Engelse muziekblad Melody Maker, waarin werd gevraagd om een drummer. De advertentie werd geplaatst door de toenmalige manager van Genesis, met de toen nog onbekende Peter Gabriel als leadzanger. Tijdens de auditie werden verscheidene drummers beluisterd, maar er was er niet één die zoveel indruk maakt als de jonge Collins. Collins baarde opzien door zijn technische manier van spelen, of zoals Tony Banks, Genesis’ toetsenist, ooit in een interview zei: “Toen Phil bij de band kwam, was hij de beste muzikant in de band.”

Behalve dat hij de drums speelde, was Collins ook de leadzanger bij enkele Genesis-nummers zoals For Absent Friends van het album Nursery Cryme en More Fool Me van het album Selling England by the Pound. In ieder geval was hij tot 1975 vaste achtergrondzanger.

In 1975, na de tournee van het album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, besloot zanger Gabriel Genesis te verlaten. Na een vruchteloze intensieve speurtocht naar een nieuwe zanger besloot Collins zelf de rol van leadzanger op zich te nemen. Op de albums bleef hij ook drummen, maar voor de liveshows werd een nieuwe drummer gezocht. In 1976/1977 was dit Bill Bruford (Yes, King Crimson). Vanaf 1977, toen Bruford zich op andere dingen wilde richten, werd de drumkruk tijdens de live optredens ingenomen door Chester Thompson (Frank Zappa, Weather Report).

Het eerste album met Collins als leadzanger A Trick of the Tail was een groot succes. Van het album werden meer exemplaren verkocht dan van alle andere vroegere Genesis-albums samen. De band was commercieel het meest succesvol met Collins als zanger. In 1978 was daar dan ook de eerste wereldhit: Follow You Follow Me.

Tijdens de jaren zeventig speelde Collins ook drums bij jazzfusionband Brand X en speelde hij op albums van onder andere Brian Eno, Robert Fripp en John Cale. In de jaren tachtig speelde Collins met onder andere Adam Ant, Eric Clapton, Howard Jones, Tears for Fears en Robert Plant.

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phil_Collins

Phil Collins – In The Air Tonight (Official Music Video)

“In The Air Tonight” was the first single from Phil Collins’ debut solo album “Face Value” in 1981.

“In The Air Tonight”

I can feel it coming in the air tonight, oh Lord

And I’ve been waiting for this moment for all my life, Oh Lord

Can you feel it coming in the air tonight, oh Lord, oh Lord

Well, if you told me you were drowning

I would not lend a hand

I’ve seen your face before my friend

But I don’t know if you know who I am

Well, I was there and I saw what you did

I saw it with my own two eyes

So you can wipe off that grin,

I know where you’ve been

It’s all been a pack of lies

And I can feel it coming in the air tonight, oh Lord

Well, I’ve been waiting for this moment for all my life, oh Lord

I can feel it coming in the air tonight, oh Lord

And I’ve been waiting for this moment for all my life, oh Lord, oh Lord

Well I remember, I remember don’t worry

How could I ever forget,

It’s the first time, the last time we ever met

But I know the reason why you keep your silence up,

No you don’t fool me

The hurt doesn’t show

But the pain still grows

It’s no stranger to you and me

And I can feel it coming in the air tonight, oh Lord

Well, I’ve been waiting for this moment for all my life, oh Lord

I can feel it in the air tonight, oh Lord, oh Lord

Phil Collins – In The Air Tonight (Live) [1080p]

“In the Air Tonight” first appeared on Collins’ 1981 solo album Face Value. Released as a single in the United Kingdom in January 1981, the song was an instant hit, quickly climbing to No. 2 on the UK Singles chart. It was also an international hit peaking at No. 19 on the Billboard Hot 100 in mid-1981 and number 1 in the Netherlands. It was later certified Gold by the RIAA representing 500,000 copies sold. The track remains one of Collins’ best-known hits. The song’s music video directed by Stuart Orme received heavy play on MTV when the new cable music video channel launched in August 1981.

Phil Collins – Dance Into The Light (Live And Loose In Paris)

It’s there in the eyes of the children

In the faces smiling in the windows

You can come on out, come on open the doors

Brush away the tears of freedom

Now we’re here, there’s no turning back

We have each other

We have one voice (we have one voice)

Hand in hand we will lay the tracks

Because the train is coming to carry you home

Come dance with me

Come on and dance into the light

Oh-oh!

Everybody dance into the light

There’ll be no more hiding in the shadows of fear

There’ll be no more chains to hold you

The future is yours – you hold the key

And there are no walls with freedom

Now we’re here, we won’t go back

We are one world

We have one voice (we have one voice)

Side by side we are not afraid

Because the train is coming to carry you home

Come dance with me

Come on and dance into the light

Oh oh

Everybody dance into the light

Do you see the sun? It’s a brand new day

All the world’s in your hands, now use it!

What’s past is past, don’t turn around

Brush away the cobwebs of freedom

Now we’re here, there’s no turning back

You have each other

You have one voice (you have one voice)

Hand in hand you can lay the tracks

Because the train is coming to carry you home

Come dance with me

Come on and dance into the light

Oh oh

Everybody dance into the light

Oh oh

Phil Collins Live 2019 ⬘ 4K 🡆 You Can’t Hurry Love ⬘ Dance Into the Light 🡄 Sept 24 – Houston, TX

You Can’t Hurry Love – 0:00 Dance Into the Light – 3:19

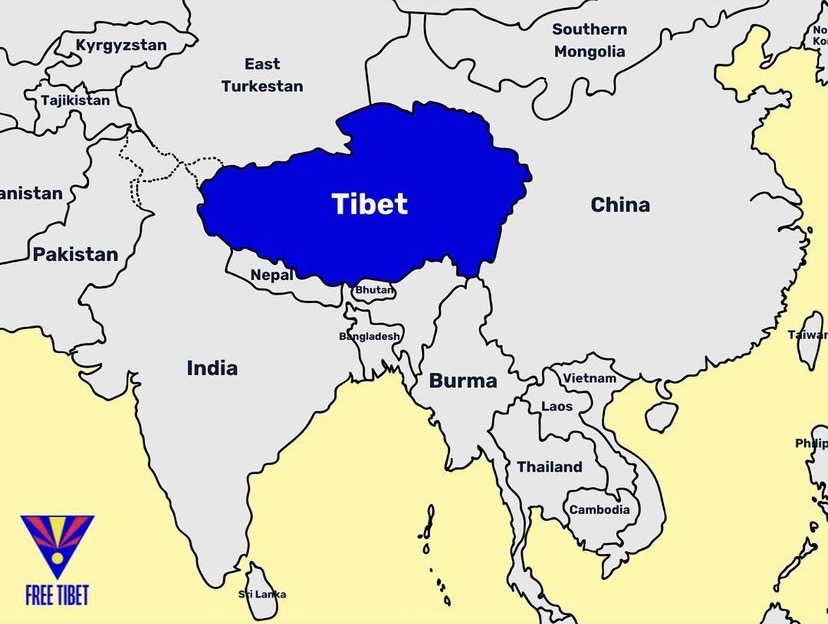

Tibet

To a Mountain in Tibet by Colin Thubron – review

“Where are you?” asks Colin Thubron in his 10th travel book, as he gulps thin Tibetan air. In the other nine volumes, the inner journey hovers between the lines as our man bushwhacks through the lost heart of Asia, bounces along the silk road in the back of a superannuated Moskvich and gnaws gristle behind the Great Wall. Now, in Thubron’s eighth decade, the inner action moves to the lines themselves. Where Are You? would have made a better title for this desperately engaging book. The author is addressing his dead mother.

To a Mountain in Tibet tells the simple story of a secular pilgrimage to the sacred slopes of Kailas in the western Himalaya. Travelling on foot with a cook, a guide and a horse man, Thubron sets out from Humla, the remotest of the Nepalese regions. Steering at first by the Karnali river, the group soon swings north-west towards the Nala Kankar Himal that shelves into Tibet, walking under walnut and apricot trees, through silent Thakuri villages and paddy fields, where traders once bartered salt and wool for lowland grains. Thubron conjures the wobble of a tin bridge over a torrent, the “cathedral shadow” of spruce and prickly oak and the two-note song of a Himalayan cuckoo over smooth grasslands. Sometimes the four seek refuge on the mud floor of a home, at other times they pitch tents, greeting, round the camp fire, stocky smugglers in bobble hats driving buffalo freighted with Chinese cigarettes.

Monasteries have always been a Thubronian leitmotif – remember the monk in Journey into Cyprus (1974) who watched the young author shaving and asked if he could pick up the World Service on his razor? A great number punctuate this latest journey, furnishing the creaking prayer wheels and fluttering flags indigenous to Tibetan narratives. The country has long held the west in thrall, the very image of an inaccessible otherworld, an exalted sanctuary and a realm of ancient learning. Thubron admits he has absorbed the romance. As an antidote, he tries to unravel the complex beginnings of the mystique and expose the reality of internal Tibetan violence centuries before 1959 and the hateful Chinese invasion. Through the direct speech of interlocutory monks, he is able to explore the shifting pantheon of regional deities – Hindu, Buddhist and shadowy, shamanic figures who waft through the hinterland.

Restraint has always been a hallmark of Thubron’s style, in the travel books at least (he also writes novels). He husbands his lyrical expression artfully. It leapt forth unexpectedly, to great effect, in the memorable first line of In Siberia (1999): “The ice-fields are crossed for ever by a man in chains.” Now, in this slim book, Thubron allows his emotional range to expand. This journey, he reveals in the opening pages, is a form of mourning for his mother, who has recently died – the last of his living family.

Deploying a poetic blend of travel and memoir, Thubron uses Buddhism to inform reflections on the cycle of life and the meaning of suffering. Or he tries to: often “memories come too hard for quiet thought”. (“The journey does not nurture reflection, as I once hoped,” he observes elsewhere. “The going is too hard, too steep.”) He describes sorting through his mother’s papers and possessions: his father’s love letters from Anzio, sepia photographs of Dalmatian puppies, a chipped tea cup. The process was, he says, “a monstrous disburdening”. After an especially breathless climb in the rarefied air at 11,000ft, hard by the Torea Pass and just before the book’s halfway mark, he recalls the moment his mother clutched at the oxygen mask for the last time, equipment lights winking, regulation curtains closing off the bed.

Juniper and birdsong diminish, and the band camps below the 15,000ft Nara Pass defile into Tibet. At half light, a herd of goats canter through, each carrying a saddlebag of salt and capering to the whistles of Humla buccaneers in conical caps. Across the border, all visitors must travel in Landcruisers to Taklakot, once the capital of an independent kingdom. But China Mobile billboards have replaced 60ft silk banners and obliterated the remnants of feudal sorcery. Taklakot is an image of “lunar placelessness” with “the gutted feel of other Chinese frontier places”. And the Mandarin-speaking Thubron is in a position to make such judgments. His 1987 Behind the Wall details a 10,000-mile solo voyage across China.

Onwards to Manasarovar, 200 square miles of water at 15,000ft, a full-blown paradise in the sixth-century Puranas and still the holiest of the world’s lakes. Here the Buddha’s mother purified herself before receiving him into her womb. (Hindus also venerate the lake.) Thubron visits a cave where Yeshe Tsogyal, Tibet’s great saint, spent his last week in a sacred trance. The trained authorial eye never fails. In the hermit’s cave, Thubron notes a spent noodle carton, peeling Sellotape and a torch without a battery.

Compared with most of his contemporaries, Thubron has, throughout a garlanded career as a grandmaster of the travel game, taken trouble to construct an elusive persona – throwing up a smokescreen, if you like. So this book breaks new ground. “I want to touch hands,” he writes, “that I know have gone cold.” In the penultimate chapter, he goes further. He summons – briefly – the memory of his only sibling Carol, dead in an Alpine avalanche at 21. One senses that something from the Grindelwald has been incubating inside this writer for half a century.

To mark this new departure, and to signal the undigested immediacy of a deeply personal journey, Thubron uses the present tense (“We come down gently . . .”). It is risky, and a favourite technique of amateurs, but he pulls it off by embedding the action in the context of its historical background. References to “some dream I had forgotten” even suggest efforts to glimpse the churning subconscious – that deep-sea region where motives glide unseen. Searching and not finding is a notion that recurs in the book. “I stare down from the cave, imaging him [a hermit] climbing the cliff towards me, but the shore stretches empty.”

One misses the sustained themes of the more substantial volumes – the disparity between political borders and ethnic realities, for example – but many of the author’s preoccupations reach maturation in these pages. The youthful faith surrendered, the reverence for “the tang of human difference”, the necessary abjuration of sentiment, the doomed pursuit of truth at all costs and a painful joy at the world’s wonder. In many ways, all Thubron’s books celebrate the terrible, pitiful, beautiful human condition.

Finally, at the climax of both journey and book, the perfect cone of Kailas. “The mountain is swathed in such a dense and changing mystique that it eludes simple portrayal,” says Thubron, hedging his bets. Isolated beyond the parapet of the central Himalaya, Kailas permeated early Hindu scriptures as the mystic Mount Meru. Buddhist texts similarly reveal the pagan gods of the mountain converting to Buddhism and dispatching a multitude of flying bodhisattvas – saints who have delayed entry to nirvana to help others – to protect the furthest crags, lighting up the mountain with their compassion.

Around the base, Thubron finds little compassion – just prostitutes and angry Chinese police swinging riot shields and truncheons (Kailas lies in a disputed border region). Thubron makes the ascent, along with hundreds of pilgrims heading to a zone of “charged sanctity” to find peace with their own dead. At the highest monastery, Choku Gompa, he finds “monks nested like swallows in little cells”, single butter lamps casting rods of light on to the snow.

During the last thousand feet of a kora (pilgrimage climb), both Hindus and Buddhists pass into ritual death. The breathless ascent will release them to new life. And so the final chapter finds Thubron at 17,000ft, where the coffee goes cold before he drinks it. He is far too wise a writer to go in for pat endings. Are there ever any, in life? “A journey is not a cure,” he says. “It brings an illusion, only, of change, and becomes at least a Spartan comfort . . . To ask of a journey, Why? Is to hear only my own silence.” To a Mountain in Tibet offers no redemption and no conclusion. Instead, it is an elegy for everything that makes us human. You can’t ask more of a book than that, can you?

Sara Wheeler’s The Magnetic North: Travels in the Arctic is published by Vintage.

The free press is under attack from multiple forces. Media outlets are closing their doors, victims to a broken business model. In much of the world, journalism is morphing into propaganda, as governments dictate what can and can’t be printed. In the last year alone, hundreds of reporters have been killed or imprisoned for doing their jobs. The UN reports that 85% of the world’s population experienced a decline in press freedom in their country in recent years.

Today we ask you to power Guardian reporting for the years to come, whether with a small sum or a larger one. If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just €2. It takes less than a minute to set up, and you can rest assured that you’re making a big impact every single month in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/feb/05/mountain-tibet-colin-thubron-review

5 dagen op propagandatrip in Tibet

Tibet is al jarenlang zo goed als afgesloten van de buitenwereld. Maar af en toe organiseert China een persreis, en mogen journalisten onder strenge begeleiding kijken hoe het de Tibetanen vergaat.

Onze correspondent Sjoerd den Daas mag – na zes jaar in China – eindelijk een keer mee met zo’n reis. Vijf dagen lang gaat hij bus in, bus uit. Elk uur van het schema staat vast, even zelf eropuit is er niet bij. Hij reist door het land van de Mount Everest, van monniken, de jak en de Dalai Lama. Makkelijk is het niet: vrijuit spreken lijkt v

The Secrets of Tibet: Ancient Land, Modern World – Full Documentary

Tibet is the rooftop of the world; home to the highest plateau on earth, the Tibetan people have thrived in this extreme alpine environments for thousands of years. Tibet is a place of ancient wonder and devoted spirituality but an emerging modernity is being woven into the tapestry of the region. These mystical people who live so close to heaven are beginning to open up and share their secrets.

Tibet, the path to Wisdom | SLICE | Full documentary

Ani Rigsang has chosen a nomadic lifestyle in the land of white clouds. The Buddhist nun felt confined in Lhasa, and so today she has taken to the road to reconnect with her country’s spiritual traditions, which are now threatened by rapid modernisation and the reinforcement of Chinese control over the region.

From snowy mountains to green valleys, from monastery to monastery, this documentary accompanies Ani as she makes her way through Tibet. A moving testimony that brings together age-old traditions and legends, this film takes us through stunning landscapes, revealing to us a contrasting Tibet, jostled by modernisation and the upheavals of its holy geography.

Documentary: “Tibet, the path to wisdom”

Direction: Hamid Sardar

Production: DreamCatcherMotionProductions, les gens bien productions for France Télévisions & Ushuaïa TV

[p. 30]

Hoofdstuk 4

Tibeert als boodschapper

Onmiddellijk riep de koning de voornaamste der vergaderde dieren samen om te bespreken, hoe zij zich van Reynaert meester konden maken.

‘Laat hem ten tweeden male door een gezant ontbieden,’ rieden de heren.

En zij noemden Tibeert, de kater, als voortreffelijke bode: hij was wel zwak, maar hij was verstandig.

En deze oplossing leek ook de koning de beste.

‘Heer Tibeert,’ zei hij, ‘ga naar Reynaert en zorg ervoor, dat hij met u aan het hof komt. Verscheidene van mijn raadslieden zeggen, dat Reynaert u vertrouwt en naar uw raad zal luisteren. Komt hij niet, dan zal het hem rouwen: men zal hem hangen zonder verder onderzoek tot schande van al zijn nakomelingen. Ga, Tibeert, en breng hem die boodschap over.’

‘Ai, heer,’ zei Tibeert, ‘ik ben een zwak schepsel, een klein dier. Als heer Brune, die sterk en dapper is, Reynaert niet mee kon krijgen, hoe zal het mij dan gelukken?’

Toen sprak de koning: ‘Heer Tibeert, gij zijt wijs en geleerd. Al zijt ge niet groot, wat hindert dat? Er is menigeen, die met list en beleid bereikt, wat hij met kracht nooit zou kunnen bereiken. Volg mijn bevelen en ga!’

‘Dat God mij dan helpe,’ zuchtte Tibeert. ‘Ik ga een werk ondernemen, dat mij zonder Gods hulp niet lukken zal. En ik ben er somber door gestemd.’

Zo moest Tibeert, met hangend hoofd en vol vrees, zijn tocht beginnen

Nauwelijks op weg zag hij in de verte een kraai komen aanvliegen. Hij werd zeer verheugd, en hij hoopte, dat de vogel aan zijn rechterkant passeren zou. Daarom riep hij: [p. 31]

‘Heil, edele zwartrok, kom tot mij en vlieg rechts.’ Maar de vogel, die een geurende bloemstruik bemerkte, stoorde zich niet aan deze woorden en vloog langs Tibeerts linkerhand. Dat scheen hem een kwaad voorteken. Was de vogel rechts gevlogen, dan zou hij het beschouwd hebben als een gunstige voorspelling. En nu was hij helemaal wanhopig. Maar hij sprak zichzelf moed in en deed, alsof hij zelf geloofde aan succes.

Zo liep hij door, totdat hij in Maupertuus kwam. Reynaert vond hij algauw: hij stond vóór zijn huis en voelde zich bijzonder opgewekt.

Tibeert zei: ‘De machtige God moge u een goede avond geven. De koning bedreigt u met de dood, als ge niet met mij naar het hof gaat.’

‘Tibeert, edele held,’ antwoordde Reynaert, ‘lieve neef, wees welkom. God geve u eer en voorspoed.’

‘t Was als altijd: Reynaert kende schone woorden in over-

[p. 32]

vloed, maar hij was vol streken en sluw als geen ander. Dat ondervond Tibeert gauw genoeg.

‘Neef,’ zei Reynaert, ‘ik vind het het allerbeste, dat gij vanavond bij mij logeert. Morgen vroeg gaan we dan samen naar het hof. Ik heb onder al mijn kennissen en bloedverwanten niemand, op wie ik zó kan rekenen als op u. Gisteren kwam Brune hier, de gulzigaard. Hij was zó grimmig en hij schijnt mij zó sterk, dat ik voor geen geld van de wereld met hem alleen de weg naar het hof had durven gaan. Maar met jou durf ik het wel; morgen met de dageraad vertrekken wij.’

Maar Tibeert zei: ‘Nee, Reynaert, het is verstandiger, wanneer we nog vanavond naar het hof gaan. De maan schijnt op de heide en het is zo licht als de dag. Er is geen betere tijd te bedenken.’

‘Nee, lieve neef,’ sprak Reynaert, ‘’t zou kunnen zijn, dat ons ‘s nachts iemand ontmoet, die ons bij dag vriendelijk zou groeten en aanspreken, maar zo láát kwaad zou doen. Blijf vannacht bij ons.’

‘Maar wat moeten we eten, Reynaert, als ik hier blijf?’ ‘Ja, daarover heb ik zorg, lieve neef. Het is een kwade tijd om voedsel te vinden. Wanneer je er trek in hebt, kun je een stuk van een honingraat krijgen! Dat is een kostelijke spijze. Hoe is het, hou je nogal van honing?’

Tibeert zei: ‘Ik moet er niets van hebben. Heb je niet wat anders in huis, Reynaert? Als je mij een vette muis bezorgen kunt, bewijs je mij een grote dienst.’

‘Een vette muis?’ vroeg Reynaert. ‘Mijn waarde neef, wat zeg je? Hier dichtbij woont een boer en die heeft naast zijn huis een schuur, waar het krioelt van muizen, de een nog dikker en vetter dan de ander. Er zijn er zoveel, dat je ze niet op een wagen zou kunnen laden. Dikwijls hoorde ik de boer erover klagen, dat ze hem nog uit zijn huis zouden verdrijven.’

[p. 33]

‘Reynaert, zijn daar zoveel vette muizen? Gave God, dat ik daar was.’

‘Tibeert, spreek je de waarheid? Wil je muizen hebben?’ ‘Of ik ze lust? Reynaert, zwijg erover. Ik heb niets liever dan muizen. Weet je dan niet, dat muizen beter smaken dan het fijnste wildbraad? Wanneer je zo vriendelijk wilt wezen, mij in die schuur van de boer te brengen, dan zal ik je mijn leven lang dienen. Ik zal je vriend zijn, al had je mijn vader en al mijn familieleden vermoord.’

‘Spot je met mij?’ vroeg Reynaert.

‘Nee, Reynaert, daar is geen sprake van.’

‘Als ik wist, dat je in ernst sprak, Tibeert, dan zou ik ervoor zorgen, dat je nog vanavond je zat kunt eten aan muizen.’

‘Zat, Reynaert, dat wil nogal wat zeggen!’

‘Tibeert, je doet niets dan schertsen.’

‘Waarlijk niet, Reynaert, zo waar ik leef. Had ik een vette muis, ik zou hem niet verkopen voor een goudstuk.’

‘Ga dan mee, Tibeert. Ik zal je brengen naar de plaats waar je je buik vol kunt eten.’

‘Met die verzekering loop ik de wereld uit met je, Reynaert.’

‘Laat ons dan vertrekken. We hebben hier al veel te lang getreuzeld.’

Zo gingen ze op weg. En ze rustten niet, vóór ze kwamen bij de schuur van de boer. Een aarden wal liep eromheen en Reynaert had daar de vorige dag een gat in gemaakt. Toen was hij erin geslaagd, een haan uit de schuur te roven. Martinet, de zoon van de boer, was daar woedend om en had nu een strik voor het gat gespannen om de vos te vangen en zo de moord op de haan te wreken. Maar Reynaert, de sluwe bedrieger, had dat al lang begrepen en hij zei nu: ‘Neef Tibeert, kruip haastig in dit gat. Grijp links

[p. 34]

en rechts. Hoor, hoe de muizen piepen! Als je genoeg hebt, kom dan weer naar buiten. Ik zal hier voor de opening op je blijven wachten. Wij moeten vanavond bij elkaar blijven en morgen gaan we samen naar het hof. Talm niet, Tibeert, eet vlug en laat ons dan naar mijn huis gaan: mijn vrouw zit met smart op ons te wachten.’

‘Wil je, dat ik in dit gat kruip, Reynaert? De boeren zijn listig; ik val ze niet graag aan.’

‘Maar Tibeert, ben je bang? Hoe kom je zo vol weifeling?’ Tibeert schaamde zich en sprong vooruit, zijn ondergang tegemoet. Want eer hij het wist, snoerde de strik hem om de hals. Zo maakte Reynaert zijn gast te schande!

Toen Tibeert de strik bemerkte, werd hij bang en sprong nog verder naar voren. En daardoor snoerde de strik nog vaster.

[p. 35]

Toen hij de knelling van het touw voelde, begon hij zo luid te schreeuwen, dat Reynaert het buiten op de weg, waar hij de wacht hield, horen kon. Hij riep: ‘Smaken de muizen goed, Tibeert, en zijn ze vet genoeg? Als Martinet wist, dat jij zo heerlijk aan wildbraad zit te smullen, zou hij je er nog een smakelijk sausje bij geven: het is een beleefde jongen. Tibeert, je zingt hoe langer hoe luider: is dat tegenwoordig de gewoonte aan het hof van de koning? Gave de machtige God, dat Isengrijn daar ook bij je was en even blij als jij, de dief en moordenaar, die hij is.’

Zo had Reynaert groot plezier over Tibeerts ongeluk. En Tibeert gilde zo luid, dat Martinet wakker werd. ‘Ha, Goddank,’ riep de jongen, ‘ik heb mijn strik op het goede ogenblik gezet; nu is de kippendief gevangen. Laten wij hem de haan betaald zetten.’

Met die woorden wendde hij zich om, nam een bosje stro, ontstak dat aan het haardvuur en wekte z’n vader en moeder en alle kinderen. ‘Wordt wakker,’ riep hij, ‘hij zit in de klem.’ Onmiddellijk sprongen ze allemaal het bed uit. Ook de boer zelf ging mee. ‘Kom hier,’ schreeuwde Martinet, ‘hij is hier.’ De boer greep het spinrokken van zijn vrouw en vrouwe Julocke een offerkaars. Bij het licht daarvan zagen ze, hoe de kater zichzelf had vastgesnoerd. En hevig ging de boer hem met het spinrokken te lijf. Maar verblind door de slagen sprong Tibeert naar voren en beet hem zo venijnig, dat hij met een luid gegil op de vlucht sloeg en neerviel. Dat gaf grote verwarring. Allen liepen op de boer toe en niemand dacht meer aan Tibeert. Ondertussen was Reynaert kalmpjes naar huis gewandeld zonder zich verder om zijn ongelukkige makker te bekommeren.

Toen Tibeert bemerkte, dat ze allemaal met de boer bezig waren, die daar zwaar gewond op de grond lag, begon hij met alle kracht op het touw te bijten en hij slaagde erin, de

[p. 36]

strik te vernielen. Hij aarzelde geen seconde, sprong uit het gat en rende naar het hof van de koning. Vóór hij daar kwam, begon het licht te worden: de zon verrees boven de horizon. Als een arme zieke stumper kwam Tibeert aan. Toen de koning zag, dat Tibeert één van zijn ogen verloren had, begon hij vreselijk te schreeuwen. Hij vroeg alle rampen van de hemel over Reynaerts hoofd. En hij gebood opnieuw al zijn baronnen, hem goede raad te geven en hem te vertellen, wat er nu tegen Reynaert gedaan moest worden. Lang zaten ze te peinzen, tot Grimbeert, de das, Reynaerts neef, sprak: ‘Heren, uw gedachten zijn zeer diepzinnig. Maar wat er ook is gebeurd, al heeft Reynaert nog zoveel kwaad gedaan, wanneer men in overeenstemming met wet en gewoonte handelt, moet hij voor de derde keer door een gezant worden opgeroepen, zoals dat bij een vrij man behoort. Komt hij dan nog niet, dan is hij schuldig

[p. 37]

aan alle misdaden, waarover men hier aan ‘t hof heeft geklaagd.’

‘Wie wil jij dan, dat hem de boodschap overbrengt?’ sprak de koning. ‘Wie is er hier, die zijn ogen of zijn wangen op het spel wil zetten voor dit kwaadaardige schepsel? Ik denk, dat wel niemand zo zot wezen zal.’

Maar Grimbeert zei: ‘Zo waarlijk als God mij helpen zal, zo zeker ben ik bereid, Reynaert op te roepen, wanneer dat uw wil is.’

‘Ga dan, Grimbeert, wees verstandig en waak.’

‘Heer koning,’ zei Grimbeert, ‘ik zal onmiddellijk vertrekken.’

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/daal003hist02_01/daal003hist02_01_0005.php#:~:text=’Heer%20Tibeert%2C’%20zei%20hij,schande%20van%20al%20zijn%20nakomelingen.