RUSSISCHE PRIMA BALLERINA OLGA SMIRNOVA VLUCHT NAAR NEDERLAND

Ze gaat meteen aan de slag bij het Nationale Ballet.

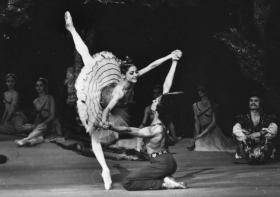

Prima ballerina Olga Smirnova heeft het beroemde Bolshoi Theater verlaten en is naar Nederland gevlucht. De ballerina, die in opspraak kwam vanwege haar kritiek op de Russische invasie, is veilig ondergebracht in Amsterdam, bevestig het Nationale Ballet.

Bolshoi Theatre’s prima ballerina Olga Smirnova, in her own words

Smirnova gaat per direct aan de slag, aldus een woordvoerder. De ballerina sprak zich onlangs uit tegen de Russische invasie in Oekraïne. “Dat maakt werken voor haar in Rusland onhoudbaar,” aldus een woordvoerder van het Nationale Ballet. Maandag is ze in Nederland aangekomen, woensdag is ze aan het gezelschap voorgesteld.

/nouveau.nl/s3fs-public/wysiwyg_images/nouveau-olga-smirnova-gi-2016.jpg?itok=9c8FEDDg)

De danseres, die een Oekraïense grootvader heeft, zei eerder op platform Telegram ‘met heel haar hart tegen deze oorlog’ te zijn. Ze had verwacht dat ‘ontwikkelde samenlevingen hun politieke problemen kunnen oplossen middels vreedzame onderhandelingen’ en had nooit kunnen denken dat ze zich voor Rusland zou schamen. Ze deed die uitlatingen toen ze nog in Rusland was, aldus de woordvoerder.

Directeur Ted Brandsen van Het Nationale Ballet noemt Smirnova ‘een exceptionele danseres’. “De achtergrond van de komst van Olga Smirnova is natuurlijk triest. Als gezelschap zijn we aan de andere kant bijzonder verheugd dat zo’n inspirerende danser zich bij ons aansluit.” Smirnova kiest volgens een woordvoerder voor Nederland omdat een samenwerking met Het Nationale Ballet ‘al lang op haar verlanglijst staat’.

Haar eerste rol danst Olga Smirnova in Raymonda die 3 april in première gaat in het gebouw van Nationale Opera & Ballet in Amsterdam. https://www.nouveau.nl/artikel/lifestyle/cultuur/russische-prima-ballerina-olga-smirnova-vlucht-naar-nederland?ref=https%3A//www.google.nl/&authId=3d1d4e87-0819-4487-a6fd-ed357d36d64e

The Russians Will Be Shocked. This Is What Their Superstar Said About The War – O2

The statement of the famous ballerina Olga Smirnoa was quoted in “The Siberian Times”, Referring to her conversation with Alesiej Ratmanski – Russian-American choreographer and former artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet.

31-year-old Olga Smirnoa is a very talented Russian ballerina. In 2016, she was promoted to ballerina in the Bolshoi Ballet. She has performed on stage all over Europe also in Beijing and Japan. She is admired all over Russia, so her recent statement by that part of the community that supports the war led by Vladimir Putin may come as a surprise.

I am against war. I never thought I would be ashamed of Russia. I’ve always been proud of talented Russians, of our cultural and sporting achievements, but now the line is being drawn before and after that. [wojnie – przyp. red] – Smirnoa admitted in an interview with choreographer Alexei Ratmansky.

“It does not mean that every Russian is likely to have relatives or friends who live there.” In Ukraine, it does not mean that my grandfather is Ukrainian and I am a quarter of Ukrainians, but we still live in the 20th century, but in fact in the 21st, ”- explains the Russian dancer.

The world-famous dancer emphasized in an interview with the former director of the Bolshoi Ballet that “political issues in contemporary times.” A civilized society should be dissolved only through peaceful negotiations.”

It pains me when people die while others are made homeless or forced to leave their homes. Who would have thought a week ago that all this would happen to us, because, although we are not in the epicenter of the fighting, we cannot remain indifferent to the global catastrophe – said Olga Smirnoa.

See also: The specialist points out problems with refugee law. “Evil is in the details” https://www.biologyreporter.com/the-russians-will-be-shocked-this-is-what-their-superstar-said-about-the-war-o2/

BOLSHOI AND KIROV BALLET COMPANIES

RUSSIAN BALLET COMPANIES

The large cities of Russia traditionally have had their own symphony orchestras and ballet and opera houses. Although funding for such facilities has diminished since the break up of the Soviet Union, attendance at performances remains high. The ballet companies of the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow and the Kirov Theater in St. Petersburg are world renowned and have toured regularly since the early 1960s. The Moscow Classical Ballet

The Perm Ballet Academy is considered the third major ballet school in Russia after the schools connected with the Bolshoi and Kirov. The school is known for combining the pure classicism of the Kirov and the power of the Bolshoi.

Perm is a Russian city in the Urals. It was where Serge Diaghilev was born, grew up and founded the Ballet Russes. Graduates of the school include the Bolshoi star Nadezhda Pavlova and the Kirov’s Olga Chenchikova and Lyubov Kunakova.

Bolshoi

The Bolshoi Ballet of Moscow is the world’s most famous ballet company. Founded in 1775 and named after the Russian word for “big and best”, the Bolshoi was little known outside of the Soviet Bloc until 1956, when it gave a command performance in London. The Bolshoi has over 250 dancers, 2,100 employees and its own orchestra. [Source: Juliet Butler, Korean Air magazine, June 1997]

Bolshoi manager Vladamir Kokorin said that there are three Russian words that all foreigners know: “Vodka, Kalashnikov and Bolshoi”. The company “captured the imagination of the West,” wrote British journalist Juliet Butler, “with its exquisite productions, it shepherding by the KGB, defections by dancing stars and rumors of despotism by the management.”

The Bolshoi ballet came into its own in the 1950s under director Yuri Grigorovich, a former dancer, choreographer and artistic director. A controversial figure he has been described by some “a genius” and “brilliant” and by others as “Stalinist” and “brutal.” As of the early 2000s the Bolshoi was under the director of Boris Akimov, a former dancer and well-respected teacher.

The Bolshoi Ballet performs in the Bolshoi Theater. Props and costumes the Bolshoi Ballet have been produced by hand since 1936 in workshop in an abandoned factory down the road from the Bolshoi theater. The Bolshoi has its own medical staff, hospital, massage parlor, kindergarten, sauna, and holiday resort. It main rehearsal halls have cracking paint and warped floor boards. The Moscow Ballet Academy is affiliated with the Bolshoi. It has branched in the United States, Japan and Korea.

Bolshoi Dancers

Bolshoi dancers have traditionally been known for their power and passion. They were often quite muscular and often bounded around like gymnasts. These days they are more delicate and lithe and resemble models.

Although big name soloists earn large sums of money, the members of the corps de ballet earned only $100 a month in the 1990s. One dancer told Butler, “False eyelashes can cost $10 and a pair of tights, $12. We have to buy all these things ourselves, so you darn your tights until you’re blue in the face…We’re expected to earn money on the side by trading our names as Bolshoi dancers. Some teach in kindergartens or schools.” Dancers are required to appear for morning dance classes even after appearing in grueling three-act ballets the night before.

A handsome male dancer, who models and dances at nightclubs told Butler, “Sometimes I’ll finish a performance like this and then go tearing off to some nightclub where I dance until three in the morning. We need the money.” When asked if she ever thought of quitting, one dancer said of course not. “People look at you differently, you can see the respect in their eyes. It took a tremendous lot of work to get here and once you’ve made it you’d be mad to leave.”

Many Bolshoi dancers smoke, get drunk and have a reputation for promiscuity and fighting among themselves. One dancer told Butler the Bolshoi is known as “one big family” because of all the wife-swapping that goes on.

Famous Bolshoi Dancers

Great Bolshoi dancers include Maya Plisetskaya, Rudolf Nureyev and Olga Lepeshinskaya. In the early 2000s, the top male dancers included Nikolau Tsisjaridze, Andrey Uvarov, Evgeny Ivanchenko. Top female dancers include Maia Alexandrovam Anna Antonicheva,

In 2003, the star Bolshoi ballerina and celebrity Anastasia Volochkova was fired because she was deemed too fat. Sshe weighed 50 kilograms and is 168 centimeters tall). A spokesman for the theater said, “She is heavy for a ballerina’ she is hard to life.” The ballerina said, “This is a planned conspiracy against me.” She sued. After a two month legal battle she was reinstated but was not given any major roles. She called the talk about her weight “humiliating and absurd for Russian ballet.” She lost her $1 million damages claim against the Bolshoi chief. She embarked on solo tours.

Hard Times for the Bolshoi

The collapse of Communism and the subsequent end of state funding produced severe financial problems for the Bolshoi. In the 1990s the Moscow theater had tattered carpets, broken bathrooms fixtures, and walls with crumbling plaster. In 1996, a 10-centimeter gap opened in one the theater’s walls. The theater was in such a bad state of repair there was talk it would be forced to close for two years for repairs. The facade was fixed with a UNESCO grant. In 1992, the Bolshoi was saved from collapse by emergency funding issued by a decree from President Yeltsin.

The Bolshoi has been accused of mismanagement, emphasizing entertainment over serious music. A lot of its top talent has left for the West. One artistic director for the opera quite after a short time because he said performers skipped rehearsals and ignored his orders.

Many ballet critics blamed the Bolshoi’s creative problems on the ballet director Grigorovich. He was replaced in 1995 by with general director Vladimir Vasiliev. Dancers loyal to Grigorovich staged a strike. Yeltsin ordered Vasiliev to restore the ballet’s luster.

In 1997 performances were widely praised. Much of the credit went to Sir Peter Ustinov, the company’s new artistic direct. Although his descendants are primarily Europeans, the Russians regard him as one of their own.

Bolshoi and Money

In the 1990s the Bolshoi got about $7.5 million from the government and about $1 million from box office receipts. The rest came from donors and money earned on foreign tours.

Efforts to earn money have tarnished the Bolshoi’s reputation. Overseas tours have been unimaginative and mediocre. In 1994, a British tour was cut short and forth of the performances for an Australian tour were canceled. Perhaps the lowest point for the Bolshoi was s series of 1996 performances at the Aladdin casino and hotel in Las Vegas in which 1,500 tickets a night were sold for the hotel’s 7,000-seat theater.

The ballet, opera and orchestras spend of the year on tour. The performers like this. When they are home they are paid in rubles, sometimes as little as $100 a month. When they are abroad they earn fees in foreign currency approaching those of Western performers.

Kirov

Although less well known that the Bolshoi, the St. Petersburg-based Kirov Ballet has distinguished it over the years as the better ballet. In the late 1800s its great director Marius Petipa choreographed the definitive interpretations of “Sleeping Beauty”, “Raymonda”, “The Nutcracker “and “Swan Lake”. Natalia Dudinskaya, Tamara Karsavina, Irina Kolpakova, Ninel Kurgapkina, Natalia Makarova all danced for the Kirov.

Named after a Bolshevik politician assassinated in 1934, the Kirov is a resurrection of the tsars Imperial Russian Ballet. The Kirov is famous for it’s the pure classicism. “The technical supremacy of the Kirov is legendary,” wrote Julie K.L. Dam in Time, “but it is the combination of athleticism and artistry that makes the company unique.”

After the collapse of Communism there were plans to change the Kirov’s name, but the ballet’s directors decided to keep the name after learning that American astronomers had name a newly discovered planet Kirov.

Kirov Training

The Vaganova Academy is affiliated with the Kirov ballet company. It was founded in 1728 and is named after Agrippina Vaganova, the legendary teacher who worked there from 1921 to 1951. Students at Vaganova have included Russia’s greatest dancers: Nijinsky, Pavlova, Balanchine, Nureyev, Baryshnikov and Makarova. Anna Pavlova described the school during Vaganova’s reign as a “convent where frivolity is banned and merciless discipline reigns.”

The Kirov has a reputation of guiding great dancers through exercises that strengthen and lengthen their muscles, giving them beautify bodies and great athletic ability. After entering, dancers are encouraged to stay with the company and teach, passing on their knowledge to a new generation.

Students at Vaganova enter when they are 9 or 10. Medical test are done at that age to determine whether they can endure the rigorous training, which lasts six days a week and goes on for eight years and is comprised of six hours of dance classes and practice a day.

Describing a senior ballet class under a 75-year-old teacher, Bob Cullen wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “In a large rehearsal hall, 11 members…begin their warm-up exercises at a bar extending along three walls. The teacher, Lyudmila Safranova…enters dressed in a severe black ensemble. ‘Don’t move the arms so much, she commands Alina Somoba, a dark-haired 17-year-old in white tights, red leotard and running shorts . ‘It’s enough to move the hands.’”

There are abut 300 students in the performing department. Only 60 students are admitted each year ad nine out of ten applicants are turned away. After eight years fewer than half graduate. Only two of the 40 or so that graduate make it to the company. Many dancers go abroad.

Kirov Today

The director of the Kirov in the early 2000s was Makkar Vaziev He was known for reenergizing the Kirov and staging sexy, energetic shows that left audiences almost gasping for air.

“Aside from the big-name stars, perhaps the truest indicator of a company’s strength is the quality of its corps de ballet,” Dam wrote in 1997. The Kirov corps resembles a field of corn being wafted by a gentle breeze, a perfectly matched body of dancers breathing and moving together.”

The Kirov has suffered from the same financial problems as the Bolshoi and its artistic director, Oleg Vinogradov, was accused of taking bribes and attacked twice by gangsters, But the company has managed to stay afloat by constantly touring and cutting corners with costumes and sets.

In 2003, the Kirov performed “Don Quixote” and “La Corsaire” at the Aladdin Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas.

Kirov Dancers

The Kirov and its home venue, the Marinsky Theater, gave the world Anna Pavlova, Vaslva Nijinsky, Mikhail Fokine, Natalia Makarova, George Balanchine, Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

In the early 2000s, the Kirov contained 28 principals dancers, including the prima ballerina Altynai Asylmuratova and lead male dancer Igor Zlensky.. Top male dancers at that time included Andrian Fadeyev and Leonid Sarafanov. The top female dancers were Daria Palenko, Irina Golub, Evgenia Obraztsova and Elena Vostritina.

The performers at the Maryinsky like touring. When they are home they are paid in rubles, sometimes as little as $100 a month. When they are abroad they earn fees in foreign currency approaching those of Western performers.

The Kirov lost more dancers to the West after the break up of the Soviet Union that the Bolshoi. It 2003, it lost one its star ballerinas, Svetlan Zakharova, to the Bolshoi.

Video: “Glory of Kirov” with Mikhail Baryshinkov, Natalia Dudinskaya, Tamara Karsavina, Irina Kolpakova, Ninel Kurgapkina, Natalia Makarova, Rudolph Nureyev

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated May 2016

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available in an effort to advance understanding of country or topic discussed in the article. This constitutes ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. If you are the copyright owner and would like this content removed from factsanddetails.com, please contact me. https://factsanddetails.com/russia/Arts_Culture_Media_and_Sports/sub9_4c/entry-5048.html

Virtual tour

MARIINSKY THEATRE

For more than two centuries the Mariinsky Theatre has been presenting the world with a plethora of great artistes: the outstanding bass and founding father of the Russian operatic performing school Osip Petrov served here; this is where such great singers as Fyodor Chaliapin, Ivan Yershov, Medea and Nikolai Figner and Sofia Preobrazhenskaya honed their skills and rose to glory. Ballet dancers reigned supreme on this stage, among them Mathilde Kschessinska, Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky, Galina Ulanova, Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov. This is where George Balanchine set out on the road to art. This theatre has witnessed the dawn of the talents of such brilliant theatre decorators as Konstantin Korovin, Alexander Golovin, Alexandre Benois, Simon Virsaladze and Fyodor Fyodorovsky among countless others.

The Mariinsky Theatre can trace its history as far back as 1783, when a Decree on the establishment of a theatre committee “for performances and music” was published on 12 July and the Bolshoi Stone Theatre was opened on Carousel Square amid great pomp on 5 October. The theatre gave the square its new name – even today it is known as Theatre Square.

Built according to plans by Antonio Rinaldi, the Bolshoi Theatre staggered the public with the sheer scale of its dimensions, its majestic architecture and its stage, equipped with the most up-to-date theatre equipment and machinery. Giovanni Paisiello’s opera Il mondo della luna was performed at the opening. The Russian Opera Company performed here in turn with the Italian and French Companies, and there were also plays and concerts of vocal and instrumental music.

St Petersburg was expanding and its image changed constantly. In 1802-1803 Thomas de Thomon – a brilliant architect and draughtsman – undertook the capital reconstruction of the interior layout and decor of the theatre, noticeably altering its external appearance and proportions. The new, grand and majestic Bolshoi Theatre became one of the architectural attractions of the capital city on the River Neva along with the Admiralty, the Stock Exchange and Kazan Cathedral. But on the night of 1 January 1811 there was a tremendous fire at the Bolshoi Theatre. In two days, the rich interior was lost and the façade was seriously damaged by the fire. Thomas de Thomon, who worked on the reconstruction plans of his darling project, did not live to see it come to fruition. On 3 February 1818 the restored Bolshoi Theatre opened once again with the prologue Apollo and Pallas in the North and Charles Didelot’s ballet Flore et Zéphire to music by the composer Caterino Cavos.

We are coming to the “golden age” of the Bolshoi Theatre. The repertoire of the “post-fire” era included Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, Die Entführung aus dem Serail and La clemenza di Tito. Russian audiences were captivated by Rossini’s La Cenerentola, Semiramida, La gazza ladra and Il barbiere di Siviglia. In May 1824 came the premiere of Weber’s Der Freischütz – a work that exerted a great influence on the birth of Russian romantic opera. There were the musical comedies of Alyabyev and Verstovsky; one of the favourite repertoire operas was Cavos’ Ivan Susanin, which was performed right up until the appearance of Glinka’s opera on the same theme. The legendary Charles Didelot is linked with the birth of the international glory of Russian ballet. It was during these years that Pushkin, who immortalised the theatre in his ageless poetry, was a regular visitor to the Bolshoi Theatre in St Petersburg.

In 1836, to improve the acoustics the architect Alberto Cavos – son of the composer and conductor – replaced the cupola ceiling of the auditorium with a flat one, above which he housed an artistic workshop and a hall for decorating the sets. Alberto Cavos removed the columns from the auditorium as they interfered with the view and distorted the acoustics; he also gave the auditorium its traditional horse-shoe shape and increased its length and height to seat up to two thousand people.

On 27 November 1836, with the first performance of Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar the reconstructed theatre opened once again. Perhaps by chance and perhaps by design, the premiere of Ruslan and Lyudmila – Glinka’s second opera – was held there exactly six years later, on 27 November 1842. These two dates would be enough to ensure that St Petersburg’s Bolshoi Theatre had earned its place forever in the history of Russian culture. But of course there were also performances of masterpieces of European music – operas by Mozart, Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, Meyerbeer, Gounod, Auber and Thomas…

In time, performances by the Russian Opera Company were transferred to the Alexandrinsky Theatre and the so-called Circus Theatre, which was located opposite the Bolshoi (where the Ballet Company and the Italian Opera Company continued to perform).

When, in 1859, the Circus Theatre was destroyed by fire, a new theatre was built on the same site, once again by Alberto Cavos. It was named the Mariinsky in honour of Empress Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander II. The first theatre season in the new building opened on 2 October 1860 with Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar under the baton of the Russian Opera Company’s conductor Konstantin Lyadov, father of the renowned composer Anatoly Lyadov.

The Mariinsky Theatre secured and developed the great traditions of Russia’s first musical theatre. With the arrival in 1863 of Eduard Nápravník, who replaced Konstantin Lyadov as Principal Conductor, a new and glorious era in the theatre’s history began. The half century Nápravník dedicated to the Mariinsky Theatre stands out for the premieres of the most important operas in the history of Russian music. We will mention just a few – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Maid of Pskov, May Night and The Snow Maiden, Borodin’s Prince Igor, Tchaikovsky’s The Maid of Orleans, The Enchantress, The Queen of Spades and Iolanta, Rubinstein’s The Demon, Taneyev’s Orest… In the early 20th century, the theatre’s repertoire included operas by Wagner (among them the tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen), Richard Strauss’ Elektra, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevronia and Musorgsky’s Khovanshchina…

Marius Petipa, who became Director of the Ballet Company in 1869, continued the traditions of his predecessors – Jules Perrot and Arthur Saint-Léon. Petipa jealously preserved classical works such as Giselle, La Esmeralda and Le Corsaire, subjecting them only to careful revisions. His production of La Bayadère brought scope and range of choreographic composition to the ballet stage for the first time, where “dance became assimilated to music.”

Petipa’s lucky meeting with Tchaikovsky, who stated that “ballet is also a symphony”, resulted in the creation of The Sleeping Beauty – a veritable poem in music and choreography. Petipa and Lev Ivanov’s collaboration produced the choreography for The Nutcracker. After Tchaikovsky’s death, Swan Lake took on a second life at the Mariinsky Theatre – and again with choreography by both Petipa and Ivanov. Petipa cemented his reputation as a symphonist choreographer with his production of Glazunov’s ballet Raymonda. His innovative ideas were seized upon by the young Michel Fokine, who staged Tcherepnin’s Le Pavillon d’Armide, Saint-Saëns’ The Dying Swan and Chopiniana to music by Chopin at the Mariinsky Theatre as well as ballets created in Paris – Schéhérazade to music by Rimsky-Korsakov and The Firebird and Pétrouchka by Stravinsky.

The Mariinsky Theatre has undergone several reconstructions. In 1885, when most productions had been transferred to the Mariinsky Theatre prior to the close of the Bolshoi, the principal architect of the Imperial Theatres Viktor Schröter added a three-storey wing to the left of the building for theatre workshops, rehearsal rooms, an electricity substation and boiler room. In 1894 under Schröter’s supervision, the wooden rafters were replaced with steel and concrete, the side wings extended and the audience foyers enlarged. The main façade, too, was subject to reconstruction, taking on monumental forms.

In 1886 ballets, which had until then continued to be performed at the Bolshoi Theatre, were transferred to the Mariinsky Theatre. The building of the St Petersburg Conservatoire was built on the site of the Bolshoi Theatre.

A government decree of 9 November 1917 made the Mariinsky Theatre the property of the State and it was transferred to the People’s Enlightenment Commissariat. In 1920 it began to be called the State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet (GATOB), and in 1935 it was named after Sergei Mironovich Kirov. Along with classics from the previous century, in the 20s and early 30s contemporary operas began to be staged at the theatre – among them Sergei Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, Alban Berg’s Wozzeck and Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier; and ballets were mounted that reinforced the new choreographic trend that had been popular for decades, the so called “drama-ballet” – Reinhold Glière’s The Red Poppy, Boris Asafiev’s Flames of Paris and The Fountain of Bakhchisarai, Alexander Krein’s Laurencia and Sergei Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet among others.

The last pre-WWII opera premiere at the Kirov Theatre was Wagner’s Lohengrin, the second performance of which ended late in the evening on 21 June 1941, though the performances announced for 24 and 27 June were replaced by Ivan Susanin. During World War II the theatre was evacuated to Perm, where there were premieres of several works including Aram Khachaturian’s ballet Gayaneh. On returning to Leningrad, the theatre opened the season on 1 September 1944 with Glinka’s opera Ivan Susanin.

In the 50s-70s such famed ballets as Farid Yarullin’s Shurale, Aram Khachaturian’s Spartacus and Boris Tishchenko’s Twelve with choreography by Leonid Yakobson, Sergei Prokofiev’s The Stone Flower and Arif Melikov’s The Legend of Love with choreography by Yuri Grigorovich and Dmitry Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony with choreography by Igor Belsky were staged at the theatre, and along with productions of these new ballets the theatre diligently cared for its classical legacy. The opera repertoire was enriched with works by Prokofiev, Dzerzhinsky, Shaporin and Khrennikov alongside operas by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Musorgsky, Verdi and Bizet.

Between 1968 and 1970 the theatre underwent a major reconstruction in line with designs by Salomeya Gelfer, as a result of which the left wing of the building was “stretched out” and took on the form it has today.

An important stage in the theatre’s history came in the 1980s with productions of Tchaikovsky’s operas Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades, staged by Yuri Temirkanov, the theatre’s Director from 1976. These productions, still in the theatre’s repertoire today, saw the emergence of a new generation of performers.

In 1988 Valery Gergiev was appointed Principal Conductor of the theatre. On 16 January 1992 the theatre’s historic name was restored and it became the Mariinsky Theatre once again. And in 2006 the company and the orchestra were presented with the Concert Hall at 20 Pisareva’ Street, built on the initiative of Valery Gergiev, Artistic and General Director of the Mariinsky Theatre. https://www.mariinsky.ru/en/about/history/mariinsky_theatre/

Ballet company founded in 1735 at St Petersburg

World famous Mariinsky (Kirov) Ballet and Opera – established 1783

Mariinskiballet

Het Mariinskiballet is een balletgezelschap, geaffilieerd met het Mariinskitheater (Russisch: Балет Мариинского театра; Baletnaij troeppa Marinskogo teatr). Het gebouw bevindt zich in Sint-Petersburg en is een van de beroemdste ballethuizen in de geschiedenis. Het gezelschap was tot het begin van de twintigste eeuw het best bekend als het Keizerlijk Ballet. Als een gevolg van de moordaanslag op Sergej Kirov werd het huis omgedoopt tot Kirovballet. Het ballethuis kreeg zijn originele naam terug na de val van het communisme.

Het was voor dit huis dat de choreograaf–balletdanser Marius Petipa essentiële werken van het ballet liet opvoeren, onder meer de herbewerking van Giselle, Het Zwanenmeer, De Notenkraker, Don Quichot en De Schone Slaapster. Ook het meesterwerk van de twintigste eeuw Spartacus werd in dit huis als eerste opgevoerd in 1956.

Als gevolg van de Oktoberrevolutie van 1917 was de balletmeester Agrippina Vaganova vastbesloten om de traditie en de methoden van het Russisch Keizerlijk Ballet voort te zetten. Haar methode legde de fundering voor de verdere ontwikkeling van het klassieke ballet in de wereld.

De choreografieschool van het Mariinskiballet, de Vaganovaschool, vernoemd naar de meest gevierde docent Agrippina Vaganova, bracht vele van de grote dansers ter wereld voort:

- Avdotia Istomina

- Paul Gerdt

- Olga Preobrajenska

- Mathilde Ksjesinska

- Anna Pavlova

- Nina Timofejeva

- Tamara Karsavina

- Olga Spesivtseva

- Vaslav Nijinsky

- George Balanchine

- Lydia Lopokova

- Galina Ulanova

- Marina Semenova

- Joeri Grigorovitsj

- Natalia Makarova

- Rudolf Noerejev

- Joeri Soloviev

- Mikhail Baryshnikov

Hoewel het ballethuis tijdens de Koude Oorlog met het probleem kampte dat sommige dansers weigerden om terug te keren uit westerse landen, maakte het ballethuis een tournee, terwijl andere huizen door de Sovjetautoriteiten naar het Bolsjojtheater in Moskou getransfereerd werden. Op deze manier verloor het huis vele dansers, zoals Ulanova, Semenova, Noerejev en Baryshnikov. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mariinskiballet

The history of the Mariinsky Ballet is closely linked with the history of European choreographic art. The beginnings and the emergence of the St Petersburg Court company are connected with the activities of foreign ballet masters. In the 18th and 19th centuries the foundations of the theatre’s ballet repertoire were laid by productions by choreographers from Italy and France who were invited to Russia who also taught in school – training Russian dancers to perform their ballets. In the late 18th century Giuseppe Canziani and Charles Le Picq were working in Russia and the first Russian choreographer Ivan Valberkh learned through their works. In the 19th century the imperial capital’s stage was ruled by ballets by the Frenchmen Charles Didelot, Jules Perrot and Arthur Saint-Léon, while in 1847 Marius Petipa made his debut in St Petersburg as a dancer and choreographer. Having taken on the post of the theatre’s Principal Ballet Master, over his lengthy career as a choreographer (spanning almost sixty years), he developed the form of grand ballet – a multi-act production, the plot combining fully developed scenes of classical ensembles, colourful character dances, genre spectacle scenes and pantomime. Even today the ballets The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake (together with choreographer Lev Ivanov) and Raymonda created with the symphonist composers Pyotr Tchaikovsky and Alexander Glazunov form part of the “gold reserves” of the classical legacy and adorn the theatre’s repertoire.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Mariinsky Ballet was famed for its galaxy of star performers: Mathilde Kschessinska, Olga Preobrazhenskaya, Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Pavel Gerdt, Nikolai and Sergei Legat and Vaslav Nijinsky. Many of these dancers presented Russian ballet during Diaghilev’s legendary Saisons russes, thanks to which Europe discovered avant-garde Russian art of the time and the St Petersburg choreographers Michel Fokine and George Balanchine who had set out at the Mariinsky Theatre and launched their international careers.

In the difficult post-Revolutionary years many Mariinsky Theatre dancers left the country. And yet to a great extent through the efforst of Fyodor Lopukhov, a connoisseur of the legacy of dance and a bold experimentalist choreographer, the theatre retained its classical repertoire. The ballet playbill expanded to include new works relating plots that were current in the new historical context.

The late 1920s and 1930s saw a veritable take-off of the dancers’ technical level: the Leningrad stage saw the arrival of Marina Semenova, Galina Ulanova, Natalia Dudinskaya, Tatiana Vecheslova, Alexei Yermolaev, Vakhtang Chabukiani and Konstantin Sergeyev. At that time drama theatre exerted a huge influence on ballet. The success of works created at the Kirov Theatre based on literary materials – Rostislav Zakharov’s The Fountain of Bakhchisarai and Leonid Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet – defined the rule of the drama-ballet on the Soviet stage in the mid 20th century. The late 1950s and 1960s at the Kirov Ballet stood out for Leonid Yakobson’s searches for plastique imagery in the form of the multi-act production and miniatures, the revival of the traditions of symphonic dance in the ballets The Stone Flower and The Legend of Love by Yuri Grigorovich and Shore of Hope and Leningrad Symphony by Igor Belsky. The success of these new productions was also ensured by the skill and expressiveness of the dancers Alla Shelest, Irina Kolpakova, Gabriela Komleva, Natalia Makarova, Alla Osipenko, Alla Sizova, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolf Nureyev and Yuri Soloviev.

In the 1970s and 1980s following a lengthy period of isolation the company revived contacts with international choreographers; the Leningrad dancers worked with Roland Petit, Maurice Béjart and Jerome Robbins. In 1989 productions by George Balanchine were included in the repertoire for the first time. Altynai Asylmuratova, Zhanna Ayupova, Galina Mezentseva, Tatiana Terekhova, Sergei Vikharev, Igor Zelensky and Farukh Ruzimatov defined the face of the ballet company in the late 20th century. Since then the Mariinsky Theatre has actively collaborated with leaders in the field of world choreography. The company has worked with John Neumeier, William Forsythe, Angelin Preljoçaj, Alexei Ratmansky, Sasha Waltz, Wayne McGregor and Hans van Manen. Their ballets, alongside works from the classical legacy, 20th century masterpieces and productions by young choreographers, comprise the ballet company’s repertoire today.

https://www.mariinsky.ru/en/company/ballet/history_ballet/