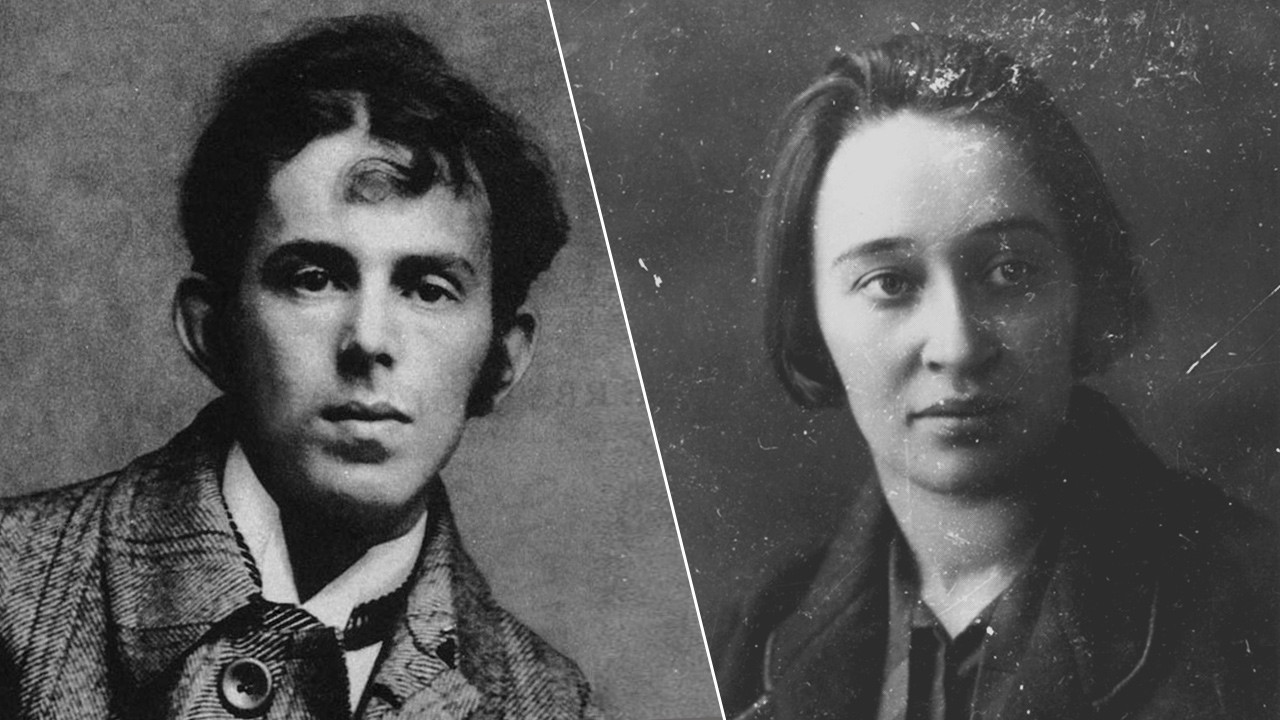

Nadjezjda Jakovlevna Mandelstam, Надежда Яковлевна Мандельштам, geboren als Nadjezjda Jakovlevna Chazina, Надежда Яковлевна Хазина) (Saratov, 31 oktober 1899 – Moskou, 29 december 1980) was een Russisch dissidente schrijfster en echtgenote van de dichter Osip Mandelstam.

Leven

Mandelstam groeide op in een Joodse familie in Kiev, waar ze kunstgeschiedenis studeerde.

In 1921 huwde ze met Osip Mandelstam. Osip werd in 1934 gearresteerd en samen met Nadjezjda verbannen vanwege zijn epigram met een voor Stalin beledigende inhoud.

Na Osips tweede arrestatie en overlijden in een doorvoerkamp in 1938 leidde Mandelstam een zwervend bestaan om arrestatie te voorkomen, waarbij ze regelmatig van adres en baan wisselde. Ze zag het als haar levenstaak de poëzie van Osip te bewaren voor het nageslacht. Ze leerde daarvoor het oeuvre van haar man uit haar hoofd.

Ze was, evenals haar man, bevriend met Anna Achmatova. Ze overleefde de Tweede Wereldoorlog met Achmatova in Tasjkent.

Memoires

Na Stalins dood kon Mandelstam terugkeren naar Moskou en publiceerde ze haar tweedelige memoires, aanvankelijk alleen in het Westen. De boeken geven een inzicht in de levenswijze van dissidente burgers in het Rusland onder Stalin. Ze bevatten een epische analyse van haar leven en een scherpe kritiek op het verval van de sovjetmoraal in de jaren twintig van de twintigste eeuw en daarna. Iedereen kon een verklikker zijn of worden. Iedereen die het regime onwelgevallig was kon worden veroordeeld. Een leven in volstrekte anonimiteit, of zoals Mandelstam zegt, door zo stil te zijn als water en zo kort als gras, leek de beste mogelijkheid om te overleven.

Naar aanleiding van de angsten die haar man moest doorstaan, en die leidden tot een zelfmoordpoging van zijn kant, kwam Nadjezjda tot een interessante beschrijving van het creatieve proces van een dichter en de psychische kwetsbaarheden die daarmee samenhangen. Ze legde er de nadruk op dat een gedicht ontstaat vanuit het onderbewuste en niet door bewuste associatie. Het daaropvolgende zoekproces naar woorden is een proces dat de dichter geheel in beslag neemt.

In 1979 droeg Mandelstam haar Osip Mandelstam-archieven over aan de Princeton University. Ze stierf op 81-jarige leeftijd.

Monument

In de Nadezjda Mandelstamstraat in Amsterdam staat het gedenkbeeld Monument voor de liefde voor Nadjezjda en Osip Mandelstam, gemaakt door Hanneke de Munck en Chatsjatoer Bjely. Naar aanleiding van de onthulling van het gedenkbeeld in september 2015 verscheen tevens een gelegenheidsuitgave, Monument voor de liefde – Osip en Nadezjda Mandelstam, met zeven gedichten van Osip Mandelstam, in een vertaling door Nina Targan Mouravi.

Herdenkings-essay Brodsky

Joseph Brodsky herdacht haar in zijn essay Nadezjda Mandelstam (1899 – 1980). Een overlijdensbericht (Nederlandse vertaling in Tussen iemand en niemand, Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 1987, pp. 150 – 161). Brodsky schreef: “In ontwikkelde kringen, in het bijzonder onder literatoren, is het zijn van een weduwe van een groot man genoeg om een eigen identiteit aan te ontlenen. Dat is in het bijzonder het geval in Rusland, waar het regime in de jaren dertig en veertig met een dermate grote effectiviteit schrijversweduwen produceerde dat er in het midden van de jaren zestig genoeg rondliepen om een vakbond mee te organiseren”. Hij prijst haar als een buitengewoon krachtige persoonlijkheid.

Bibliografie

- Memoires [eerste deel van de memoires, in het Engels getiteld Hope against Hope], Amsterdam: Van Oorschot, 1971. ISBN 90-282-0260-9

- Tweede boek [tweede deel van de memoires, in het Engels getiteld Hope Abandoned], Amsterdam: Van Oorschot, 1973. ISBN 90-282-0288-9

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelstam (Russian: Надежда Яковлевна Мандельштам, IPA: [nɐˈdʲeʐdə ˈjakəvlʲɪvnə mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam], née Khazina, Хазина; 30 October [O.S. 18 October] 1899 – 29 December 1980) was a Russian Jewish writer and educator, and the wife of the poet Osip Mandelstam who died in 1938 in a transit camp to the gulag of Siberia. She wrote two memoirs about their lives together and the repressive Stalinist regime: Hope Against Hope (1970) and Hope Abandoned (1974), both first published in the West in English, translated by Max Hayward.

Of these books the critic Clive James wrote, “Hope Against Hope puts her at the centre of the liberal resistance under the Soviet Union. A masterpiece of prose as well as a model of biographical narrative and social analysis it is mainly the story of the terrible last years of persecution and torment before the poet [her husband Osip] was murdered. The sequel, Hope Abandoned, is about the author’s personal fate, and is in some ways even more terrible, because, as the title implies, it is more about horror as a way of life than as an interruption to normal expectancy. [The two books] were key chapters in the new bible that the twentieth century had written for us.”

Early life and education

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Khazina was born in Saratov, southern Russia, the youngest of four children (she had a sister and two brothers) of a middle-class Jewish family. Her parents were Yakov Arkadyevich Khazin and Vera Yakovlevna Khazina, and the family was wealthy enough to travel. Her mother was among the first group of women in the Soviet Union to complete training as a medical doctor, and her father was an attorney. The family did not practice Judaism, and kept Russian Orthodox holidays. Later they converted to Christianity. The family moved to Kiev, Ukraine, for her father’s work, and the greater cultural and educational opportunities of the larger city. There she attended school. After gymnasium (secondary school), Nadezhda studied art.

Career

Nadezhda met the poet Osip Mandelstam at a nightclub in Kiev in 1919, and they started a relationship which led to marriage in 1921–1922. They lived in Ukraine at first, but moved to Petrograd in 1922. Later they lived in Moscow, and Georgia.

Osip was arrested in 1934 for his poem entitled “Stalin Epigram” and exiled to Cherdyn, in Perm Oblast; Nadezhda went with him. Later the sentence was lightened and they were allowed to move to Voronezh in southwestern Russia, but were still banished from the largest cities, which were the artistic and cultural centers.

After Osip Mandelstam’s second arrest in May 1938 and his subsequent death at the transit camp “Vtoraya Rechka” near Vladivostok that year, Nadezhda Mandelstam led an almost nomadic life. Given the repression of the times, she tried to dodge an expected arrest, and frequently changed places of residence and took only temporary jobs. On at least one occasion, in Kalinin, the NKVD came for her the day after she had fled.

As her mission in life, she worked to preserve her husband’s poetic heritage, with the goal of publication one day. She managed to keep most of it memorized because she did not trust paper. Many years later, she was able to work with other writers to have it published.

Through the terrible years, Nadezhda Mandelstam gained her college degree and taught English in various provincial towns. After the death of Joseph Stalin on 5 March 1953, when government’s repression eased, she returned to her studies and completed her dissertation in linguistics (1956).

She was not allowed to return to Moscow until 1964, following the first phase of Osip Mandelstam’s rehabilitation (under Nikita Khrushchev). She had spent 20 years in a kind of internal exile until the “thaws” of the late 1950s. Nadezhda began writing her memoir, which was published in English as Hope Against Hope in 1970, in part as a way of restoring her husband’s memory and integrating her own struggles. It first circulated in a samizdat version in the Soviet Union in the 1960s.

In her memoirs, Hope Against Hope (1970, 1977) and Hope Abandoned (1974, 1981), first published in the West, she made an epic analysis of her husband’s life and times. She elevated her husband as the figure of an artistic martyr under Stalin’s repressive regime. She criticized the moral and cultural degradation of the Soviet Union of the 1920s and later. The titles of her memoirs are puns, as nadezhda in Russian means “hope”.

In 1976, Mandelstam gave her archives to Princeton University in the United States.

In 1979, her heart condition deteriorated, and she took to her bed in early December 1980.[7] Nadezhda Mandelstam died on 29 December 1980 in Moscow. The funeral was arranged in the Russian Orthodox rite, with the lying in state taking place on 1 January 1981, in the church of Our Lady of the Sign. She was buried on 2 January 1981, at the Kuntsevo Cemetery.

4 Poems by Osip Mandelstam

Over the next several weeks Rutgers’s James McGavran will be joining us to share his translations of major Russian poets. Today we begin our new poetry series with the work of Osip Mandelstam.

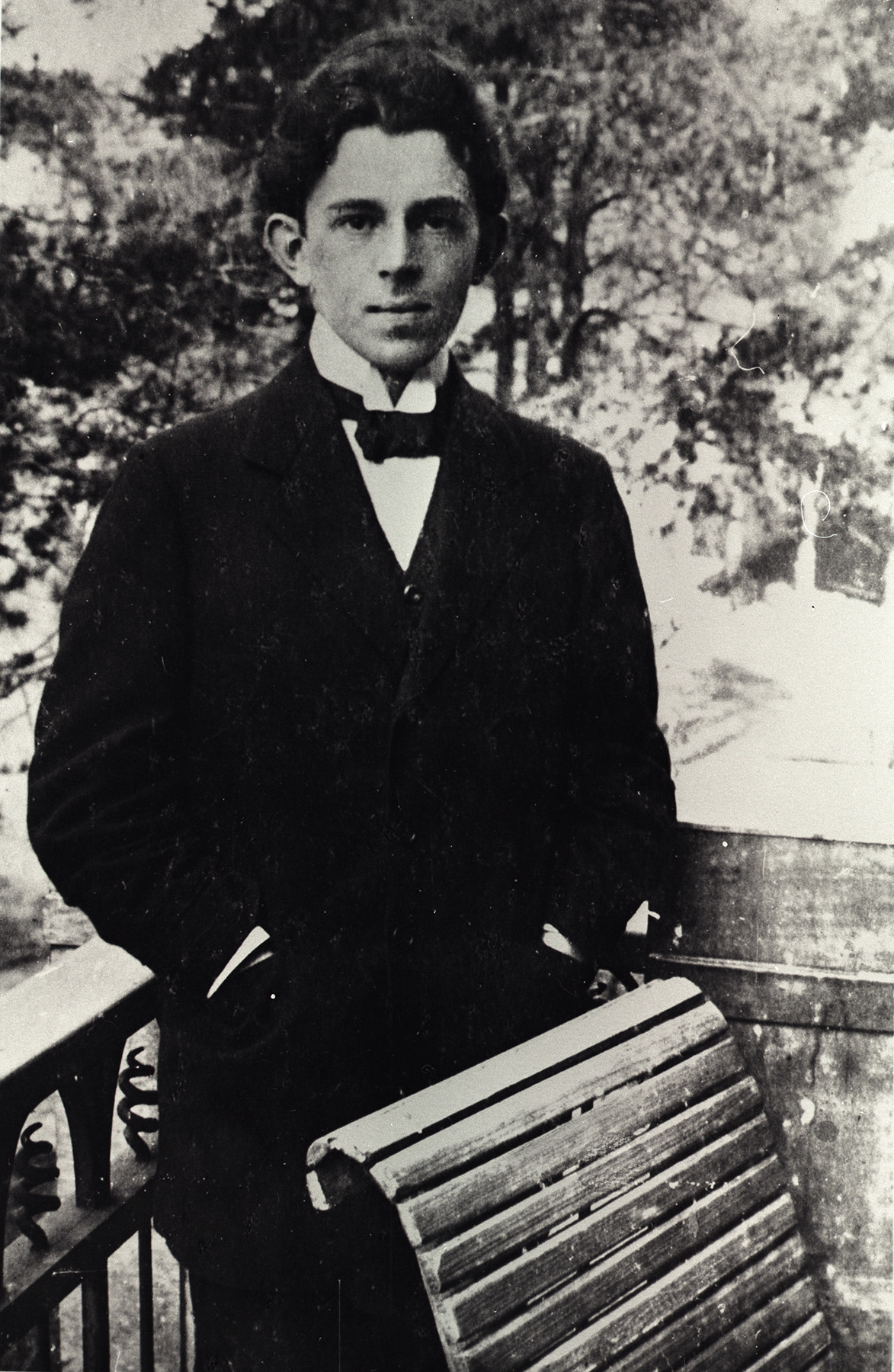

Undoubtedly one of the greatest poets of the 20th century, Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) was born in Warsaw but grew up in St. Petersburg. Early in his career he was a founding member of the Acmeist school of poets that also included Anna Akhmatova and Nikolai Gumilyov; Mandelstam’s first collection of poems, Stone (1913), brought him instant recognition as one of the most talented writers of the younger generation. Further collections followed in the early 1920s, as Mandelstam’s style became more and more complex, his imagery more and more dense and layered. It is on his final five notebooks of poems, which were never published in his lifetime, that his reputation primarily rests, for they attain a verbal texture and richness of meaning unmatched in Russian poetry. The notebooks, which contain all his poetic output from 1930 to 1937, were preserved by Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, until they could be published abroad. Mandelstam was arrested twice during the 1930s, originally because of an epigram he wrote on Stalin in 1933. His first arrest resulted in exile (together with his wife) in the southern city of Voronezh; after his second arrest on May 5, 1938, he was sentenced to five years in the Gulag and died in a transit camp near Vladivostok on December 27.

The Age

My age, my beast, who will ever

Look into your eyes

And with his own blood glue together

The backbones of two centuries?

Blood the builder gushes

From the throat of earthly things,

Only the parasite trembles

On the threshold of new days.

As long as it holds life, a creature

Must carry to the end a spine,

And a wave plays

With the unseen backbone.

Like a child’s tender cartilage

Is the age of earth’s infancy—

Once more, like a sacrificial lamb,

The crown of life’s skull is offered up.

To wrest the age from captivity,

To begin a new world,

The knees of gnarled and knotted days

Must fit together like a flute.

It is the age that rocks the wave

With human yearning,

And in the grass an adder breathes

The golden measure of the age.

And again the buds will swell,

Shoots of greenery will spring up,

But your backbone is broken,

My beautiful, pathetic age.

And with a senseless smile

You look back, both cruel and weak,

Like a beast that once was lithe,

Upon the prints of your own paws.

Blood the builder gushes

From the throat of earthly things,

And the seas’ warm cartilage

splashes ashore like a burning fish.

And from the high bird netting,

From humid billows of azure

Cool indifference pours, pours down

On your mortal injury.

1922

He Who Has Found a Horseshoe

(A Pindaric Fragment)

We look at a forest and say:

Here’s ship timber, mast timber,

Red pines

Free to their very crowns of any bushy burden,

They should be creaking in a gale,

Like solitary stone pines

In the frenzied forestless air;

Under the salt heel of the wind the plumbline will hold true, fitted to the dancing deck,

And the navigator,

In his unbridled thirst for space,

Dragging through damp ruts

The fragile instrument of a geometrician,

Will collate against the pull of the earth’s bosom

The ragged surface of the seas.

But breathing in the smell

Of the resin tears exuded through the ship’s planking,

Admiring the boards,

Riveted, arranged into bulkheads

Not by the peaceful carpenter of Bethlehem, but by another—

The father of voyages, the seafarer’s friend—

We say:

They too stood on land,

Uncomfortable land, like a donkey’s back,

Their crowns oblivious to their roots

On a celebrated mountain ridge,

And clamored under freshwater downpours,

Vainly offering to exchange their noble cargo to the sky

For a pinch of salt.

Where to start?

Everything is cracking and reeling.

The air shivers with similes.

No one word is better than another,

The earth buzzes with metaphor,

And light two-wheeled carts

Flamboyantly harnessed to flocks of birds, flocks dense with the effort,

Break into pieces,

Vying with snorting hippodrome favorites.

Thrice blessed is he who puts a name into his song;

A song adorned with a title

Lives longer among the others—

She is marked among her girlfriends by a fillet on the brow

That cures her from unconsciousness and overpowering, intoxicating smells—

Whether it be the nearness of a man,

The smell of a powerful beast’s fur,

Or simply a breath of thyme rubbed between the palms.

Air can be dark like water, and all things living swim in it like fish,

Fins pushing against the sphere,

Dense, resilient, barely warmed—

A crystal in which wheels are set in motion and horses shy,

Neaera’s moist black earth, plowed up anew each night

By pitchforks, tridents, hoes, plows.

The air is mixed as stiffly as earth—

You cannot get out of it, and it is hard to get in.

A rustle runs through the trees like a green ball game,

Children play knucklebones with the vertebrae of dead animals.

The brittle chronology of our era nears its end.

Thank you for all that was:

I myself was mistaken, I lost my way, lost count.

The era rang like a golden globe,

Hollow, cast, supported by no one,

At every touch answering “yes” and “no.”

The way a child answers:

“I will give you an apple,” or, “I will not give you an apple.”

And his face is an exact copy of the voice that pronounces these words.

The sound still rings, though the cause of the sound has vanished.

A horse lies in the dust and snorts, in a lather,

But the sharp bend of its neck

Still preserves the memory of the race, with legs flung wide,”

When there were not four of them,

But as many as there were stones in the road,

Renewed in four shifts,

Numerous as the push-offs from earth

Of a blazing pacer-horse.

So,

He who has found a horseshoe

Blows the dust off it

And burnishes it with wool till it shines;

Then

He hangs it over the threshold

So that it might rest

And no longer have to strike sparks from flint.

Human lips that have nothing more to say

Preserve the shape of the last word said,

And in the hand there remains a sensation of heaviness,

Though the jug splashed half empty on the way home.

What I say now is said not by me,

But dug up from the earth like grains of petrified wheat.

Some

……. on their coins depict a lion;

Others,

…….a head.

Various little tablets of copper, gold, and bronze

Lie with identical honor in the earth.

The age, trying to gnaw through them, imprinted on them its teeth.

Time pares me down like a coin,

And there is no longer enough of me left for myself.

1923

* * *

For the resounding valor of ages to come,

For the sake of a high race of men,

I forfeited a cup at the feast of my fathers,

And merriment and my honor.

On my shoulders pounces the wolf-hound age,

But I am no wolf by my blood;

Thrust me, instead, like a hat up the sleeve

Of the Siberian steppe’s warm fur coat,

So I can’t see the coward or the soft bit of grime

Or the bloodied bones on the wheel;

So that all night the blue-fox furs might shine

For me in their primeval beauty.

Lead me into the night where the Yenisei flows

And the pine reaches up to the star,

Because I am no wolf by my blood

And only my equal will kill me.

March 17–28, 1931

Lines on the Unknown Soldier

1

Let this air bear witness:

His long-range heart,

And in the dugouts the active and omnivorous

Windowless ocean—matter…

How denunciatory these stars are!

They just have to look down—what for?

At the censure of the judge and the witness,

At the windowless ocean, matter.

The rain remembers, dreary sower—

His nameless manna—

How little woodland crosses marked

The ocean or the battlefield.

Cold, sickly people will continue

To kill, to endure cold, to go hungry,

And in his renowned grave

The unknown soldier is placed.

Teach me, sickly swallow,

You who have forgotten how to fly,

How I can control this aerial grave

With no rudder and no wing.

And on behalf of Mikhail Lermontov,

I’ll give you a strict account,

How the grave teaches the slouch

And the aerial pit draws one in.

2

Like fidgeting grapes

These worlds threaten us

And hang like stolen cities,

Like golden slips of the tongue, like denouncements,

Like berries of poisonous cold—

Huge tents of tensile constellations,

Constellations’ golden oil…

3

Arabian horse mash, a medley,

The light of speeds ground up into a ray,

And with its slanting soles

The ray stands on my retina.

Millions murdered on the cheap

Beat a path in the emptiness—

Goodnight! Wish them all the best

On behalf of the earthen fortresses!

Incorruptible sky, sky of trenches—

Sky of mass, wholesale death—

After you, away from you, aggregate sky,

My lips carry me through the dark—

Past craters, past embankments and talus

Among which he lingered in the haze:

All ruined—the sullen, pockmarked

And humiliated genius of graves.

4

The infantry dies well

And well sings the nocturnal chorus

Above Shveik’s flattened smile,

Above Don Quixote’s avian lance,

And above the chivalrous avian metatarsus.

And the cripple and man shall be friends—

There’s plenty of work for them both,

And along the outskirts of the age thumps

A family of wooden crutches—

Quite a partnership, terrestrial globe!

5

Is that why a skull must develop

Forehead-wide—from temple to temple—

So that into its dear eye sockets

The troops cannot help but pour?

A skull develops because of life

Forehead-wide—from temple to temple—

Mocks the smoothness of its own sutures,

Like an understanding cupola shines clear,

Foams over with thought, dreams of itself—

Goblet of goblets, fatherland to the fatherland,

Cap sewn with starry seams,

Cap of happiness—Shakespeare’s father…

6

The clarity of ash trees, the vigilance of sycamores,

Slightly red-shifted, speeds to its home,

As if overstocking with fainting fits

Both skies with their lackluster fire.

We are allied only to that which is surplus,

Ahead lies not a downfall, but a botched measurement,

And to struggle for one’s minimum wage of air—

This glory is unlike any other.

And overstocking my consciousness

With half-fainted being,

Is it I who, with no choice, drinks this slop,

Do I eat my own head under fire?

Is that why the tare of charisma

Is prepared in the empty space,

So white stars might turn back and,

Slightly red-shifted, speed to their home?

Do you hear, stepmother of the star gang,

Night, what is coming now and later?

7

Aortas strain with blood,

And a whisper resounds through the ranks:

—I was born in ninety-four…

—I was born in ninety-two…

And, clutching in my fist the rubbed-out

Year of my birth, with the throng, en masse,

I whisper through blood-drained lips:

—I was born in the night between the second and third

Of January in ninety-something-or-other—

An unreliable year—and the centuries

Surround me with fire.

March 2, 1937–1938

James McGavran received a Ph.D. in Slavic languages and literatures from Princeton University in 2008. He has taught Russian language and culture courses at Kenyon College and St. Olaf College, and he begins work as an instructor of Russian at Rutgers University in the fall of 2013. His book of annotated translations of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, Selected Poems, is now available from Northwestern University Press, and he has also published articles and translations in Slavonica, Modern Poetry in Translation, and Slavic and East European Journal. He is currently working on a collection of translations of Osip Mandelstam and a cultural history of chess in Russia and the Soviet Union.

Osip Emiljevitsj Mandelstam of Mandelsjtam (Russisch: О́сип Эми́льевич Мандельшта́м) (Warschau, 15 januari 1891 – Vtoraja Retsjka nabij Vladivostok, 27 december 1938) was een Joods–Russisch dichter en essayist. Hij wordt beschouwd als een van de grootste Russische dichters van de twintigste eeuw. De Klassieke Oudheid en de Mediterrane wereld spelen in zijn schrijven een grote rol. Zijn werk was in de Stalin-tijd vrijwel onbekend buiten Rusland en mocht niet of slechts incidenteel gepubliceerd worden. Mandelstams essays en poëzie wordt samen met die van Innokenti Annenski, Anna Achmatova en Nikolaj Goemiljov, gerekend tot het Acmeïsme. De eerste gedichten van Mandelstam waren onpersoonlijk, maar later begon hij ook meer expliciet met de dichterlijke analyse van zijn eigen ervaringen, de geschiedenis en de actuele ontwikkelingen in politiek en samenleving.

Leven en werk

Osip Mandelstam werd geboren in Warschau, dat toen nog onderdeel was van het Russische Rijk en groeide op in Leningrad. Zijn vader was een succesvol handelaar in leerproducten en zijn moeder was pianolerares. Beide ouders waren joods, maar niet erg praktiserend. Thuis werd Mandelstam onderwezen door gouvernantes en privéonderwijzers en toen hij oud genoeg was, stuurden zijn ouders hem naar de prestigieuze Tenisjev-school, waar hij van 1900 tot 1907 verbleef. In 1907 reisde hij af naar Parijs en later naar Duitsland, waar hij van 1909 tot 1910 oude Franse literatuur bestudeerde aan de Universiteit van Heidelberg. Na zijn kortstondige studie in Duitsland reisde hij terug naar Rusland, waar hij van 1911 tot 1917 filosofie studeerde aan de universiteit van St. Petersburg. In 1921 trouwde hij met Nadjezjda Mandelstam. Zijn vrouw wist later, in de tijd dat publicatie vrijwel onmogelijk was geworden en geschreven teksten gevaarlijk waren, veel van de gedichten van haar man te bewaren voor het nageslacht door ze uit het hoofd te leren.

Mandelstam debuteerde in 1910 in het tijdschrift Apollon en in 1911 werd hij lid van het ‘Dichtersgilde’, waarin de acmeïsten verenigd waren. Als dichter verwierf hij faam met de gedichtenbundel Kamen (steen), die in 1913 verscheen. De onderwerpen van de gedichten in de bundel waren divers en liepen uiteen van muziek tot de architectuur uit de klassieke oudheid. Kamen werd gevolgd door de bundels Tristia (1922) en Stichotvorenija 1921-1925 (1928).

Naast zijn dichtwerk schreef hij tussen 1913 en 1935 essays. Eén daarvan, het Gesprek over Dante (1933) is in een Nederlandse vertaling uitgegeven (naast de oorspronkelijke tekst). Hij probeert daarin, aan de hand van de La divina commedia van Dante Alighieri, onder andere aan te tonen waarom de dichtkunst meer is dan de som van zijn delen. Bekende beelden daaruit zijn ‘het duurzame tapijt geweven uit draden van water’ en, om de veelzijdigheid en betekenisrijkdom van gedichten aan te geven, ‘de oversteek van een brede rivier over Chinese jonken die allerlei verschillende kanten opvaren’.

Mandelstam ging echter gebukt onder armoede. Hij moest in zijn onderhoud voorzien met het schrijven van kinderboeken en het vertalen van werk van onder anderen Upton Sinclair, Jules Romains en Charles de Coster. Van 1925 tot 1930 schreef hij alleen maar proza. In 1930 maakte hij een reis naar Armenië, wat het laatste grote werk opleverde dat nog gepubliceerd werd tijdens zijn leven. Hij reisde door de meest afgelegen provincies van Armenië. Zogenaamd als journalist, om zijn vijanden, de machthebbers in Moskou, van zich af te houden, die hem verdachten van staatsondermijnende sympathieën.

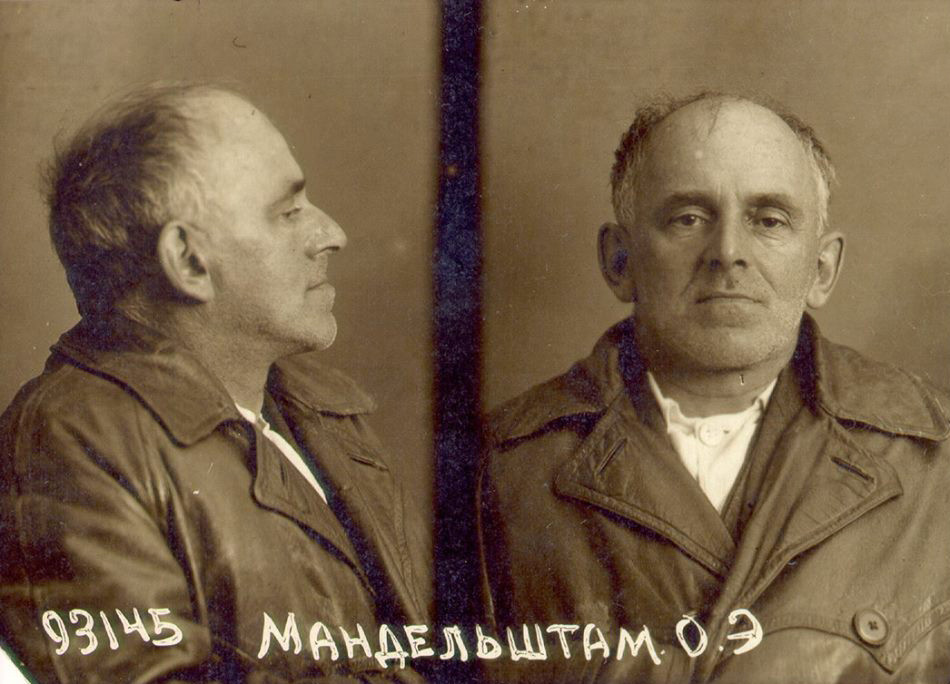

Mandelstam werd in 1934 gearresteerd vanwege het gedicht “de heerser” dat Stalin als een persoonlijke belediging opvatte. In dit gedicht werd Stalin omgeschreven als “Kremlinbewoner uit de bergen, de wurger en boerendoder // zijn dikke vingers vet als wormen // en zijn woorden onwrikbaar als loden gewrichten // zijn kakkerlakkensnor lacht etc”. (vert. Kees Verheul). Naar aanleiding van dit gedicht werd Mandelstam verbannen naar het plaatsje Tsjerdyn in de Oeral, maar na een zelfmoordpoging werd zijn verbanning verplaatst naar Voronezj. Zijn verbanning eindigde in 1937. In 1938 werd hij weer opgepakt, wegens vermeende antirevolutionaire activiteiten en tijdens zijn ondervraging bekende hij een antirevolutionair gedicht geschreven te hebben. Mandelstam werd veroordeeld tot vijf jaar in een werkkamp, maar lang voordat hij aankwam op zijn bestemming was hij al zo verzwakt, dat hij in een van de vele doorgangskampen bezweek. Hij stierf in een Goelagkamp in Vtoraja Retsjka, in de buurt van Vladivostok, op 27 december 1938.

Mandelstam werd internationaal bekend en beroemd in 1970, toen zijn geschriften in het westen werden gepubliceerd. Mandelstams verhaal “De Egyptische postzegel” verscheen samen met autobiografische teksten in de gelijknamige bundel in 1978 bij Uitgeverij Van Oorschot in de reeks Russische Miniaturen. Zijn weduwe, Nadjezjda Mandelstam, publiceerde haar tweedelige memoires, waarin haar leven met Mandelstam in het tijdperk van Stalin in al zijn facetten uit de doeken werd gedaan. Mandelstams Voronezj-gedichten, gepubliceerd in 1990, geeft het beste beeld van het verdere werk dat hij had willen schrijven als hij de Goelagarchipel had overleefd.

Joseph Brodsky noemde hem, in zijn rede bij de aanvaarding van de Nobelprijs voor Literatuur (1987), zijn grote leermeester. [1]

De liefde tussen Nadjezjda en Osip Mandelstam werd in 2010 en 2015 gevierd door twee beelden; een in Sint-Petersburg en de ander in Amsterdam onder de titel Monument voor de liefde van Hanneke de Munck en Chatsjatoer Bjely, waarop een van Osips gedichten is geplaatst.

Gedicht

Bronzen kunstwerk van Hanneke de Munck en Chatsjatoer Bjely voorstellende Osip en Nadezjda Mandelstam, geplaatst in 2015

Kinderboeken lezen, meer niet,

Slechts te denken in kindergedachten,

Het volwassen gedoe te verachten,

Op te staan uit een peilloos verdriet.

(vertaling Marja Wiebes en Margriet Berg)

Publicaties van Osip Mandelstam in Nederlandse vertaling

- Osip Mandelstam: Gesprek over Dante, (vertaling: Peter Zeeman) Slavische Cahiers Nr. 32, Pegasus, Stichting Uitgeverij, oktober 2018. ISBN/EAN-nummer: 9789061434429.

- Monument voor de liefde – Osip en Nadezjda Mandelstam. Gelegenheidsuitgave naar aanleiding van onthulling gedenkbeeld in september 2015 in de Nadezjda Mandelstamstraat te Amsterdam. (Vertaling van zeven gedichten van Osip Mandelstam door Nina Targan Mouravi; daarnaast bijdragen van Willem G. Weststeijn, Hanneke de Munck, Pavel Nerler, Sietse H. Bakker), Pegasus Uitgeverij, Amsterdam, 2015. ISBN 978-90-614-3407-8

- Osip Mandelstam: Neem mijn verzen in acht: gedichten (vert. Margriet Berg e.a.). Amsterdam, Atlas, 2010. ISBN 978-90-450-1350-3

- Osip Mandelstam: Europa’s tedere handen: gedichten, brieven, essays (vert. Nina Targan Mouravi). Amsterdam, Azazello, 2007. Met CD. ISBN 978-90-808825-5-3

- Šestoe čuvstvo = Het zesde zintuig: gedichten van Anna Achmatova, Nikolaj Goemiljov en Osip Mandelstam (vert. Marja Wiebes en Margriet Berg). Leiden, Plantage, 1997. ISBN 90-73023-51-3

- Osip Mandelstam: Reis naar Armenië (vert. Kristien Warmenhoven; inl. Bruce Chatwin) Houten, Het Wereldvenster, 1990. ISBN 90-269-4087-4

- Osip Mandelstam: Zwarte aarde – schriften uit Voronezj (vert. Miriam Van Hee en Peter van Everbroek). Leuven, Kritak, 1986. ISBN 90-6303-171-8

- Osip Mandelstam: Laatste brieven, 1936-1938 (vert. Yolanda Bloemen). Maastricht, Gerards & Schreurs, 1986. ISBN 90-70850-05-2

- Kwartet: Osip Mandelstam, Anna Achmatova, Marina Tsvetajeva en Boris Pasternak. (vert. Charles B. Timmer). Amsterdam, De Arbeiderspers, 1982. ISBN 90-295-4870-3

- Osip Mandelstam: De Egyptische postzegel (vert. T. Eekman en Ch. B. Timmer). Amsterdam, Van Oorschot, 1978. (Russische Miniaturen, deel 4. ISBN 90-282-0449-0 (2e druk, 1979, ISBN 90-282-0450-4)

- Osip Mandelstam: Wie een hoefijzer vindt (en andere gedichten) (vert. Kees Verheul). Amsterdam, Van Oorschot, 1974. ISBN 90-282-0313-3 (2e, herziene en met essays vermeerderde uitgave, 1982, ISBN 90-282-0546-2)

Externe link

5 reasons you should know genius anti-Stalin poet Osip Mandelstam

Vadim Nekrasov/Global Look Press, Getty Images

1. He was the last Russian intellectual

Vadim Nekrasov/Global Look Press

Osip Mandelstam was born into a Jewish merchant family in Warsaw and later moved to St. Petersburg where he received his secondary education at a prestigious school. He also studied at the Sorbonne and at Heidelberg University. He made his first steps as a poet in association with the Acmeist poets (Anna Akhmatova and Nikolay Gumilyov). He was fascinated by antiquity and by French poets Paul Verlaine, Charles Baudelaire, and François Villon, and had a brief affair with poet Marina Tsvetaeva.

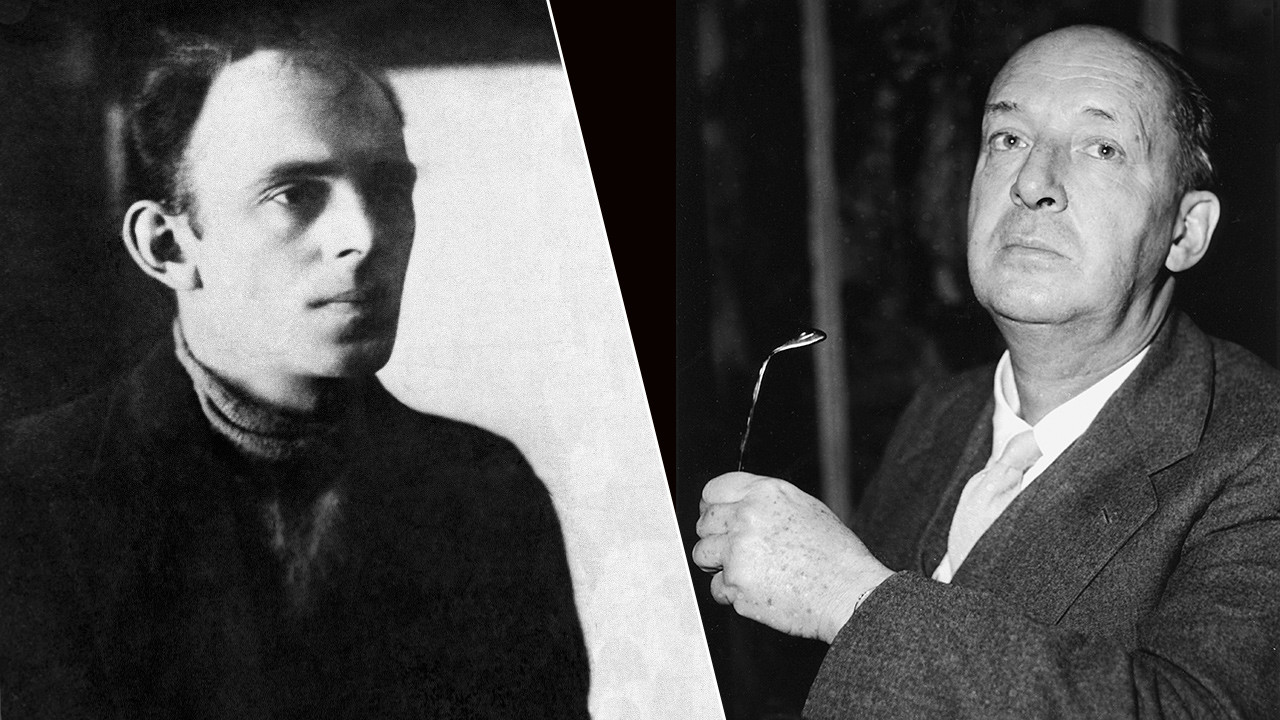

For many intellectuals in Russia today, two poets – Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) and Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996) – have acquired a nearly sacred status. Both are presented almost in the guise of Christian martyrs, as poets who suffered for their verse: One died at the hands of the authorities and the other was forced to emigrate. And yet, if the life of Brodsky was rather successful – he was awarded the Nobel prize and recognized around the world – the no less brilliant Mandelstam fell victim to political repression and sank into oblivion for many years.

2. He is the author of the most famous anti-Stalin verse

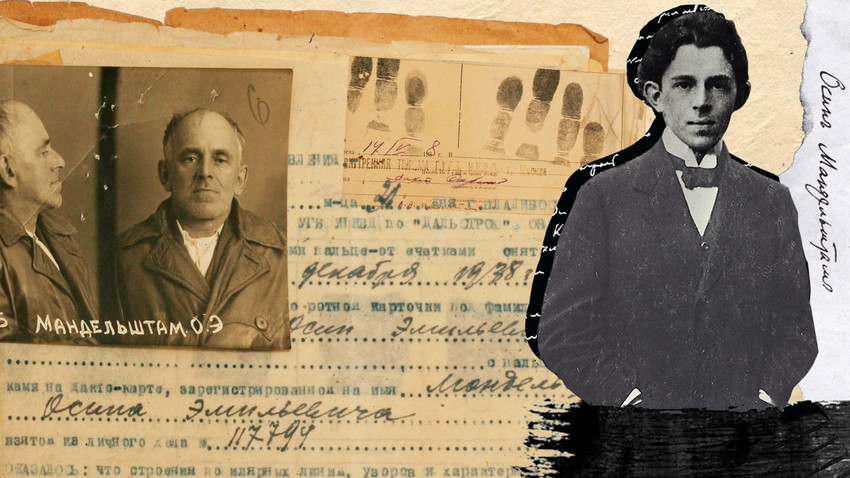

NKVD profile photo of Mandelstam

Public Domain

In 1933, at the height of Stalin’s cult of personality, Mandelstam wrote the poem We live without feeling the country beneath us, which contained unthinkable criticism of Stalin. He calls the Great Leader the “Kremlin mountaineer” and accuses the authorities of ignoring ordinary people: “Our speech at ten paces inaudible.” He describes the entourage of the Leader of the Peoples as a “rabble” who merely carry out orders. [The above quotes are taken from the translation by David McDuff].

It goes without saying that the poem was never published either in Mandelstam’s lifetime or for a long time afterwards. It was dangerous even to write it down: Mandelstam recited it to friends, but Boris Pasternak called it suicidal and asked him not to repeat it to anyone. The state security archives only have one surviving autographed copy.

Anyway, Mandelstam was prepared for the most terrible outcome, although at first he was only exiled to Voronezh. The poet was arrested in 1938 before dying in a transit camp in the Far East.

And yet, the poem has survived: It was published in the West in 1963 in the Mosty [Bridges] journal, to which it was passed by literary historian Yulian Oksman (thanks to him, many verses of the poets of the Silver Age not published in the Soviet period are extant). That was the beginning of Mandelstam’s rise to fame in the West.

3. He is regarded as one of the most significant poets of the Silver Age

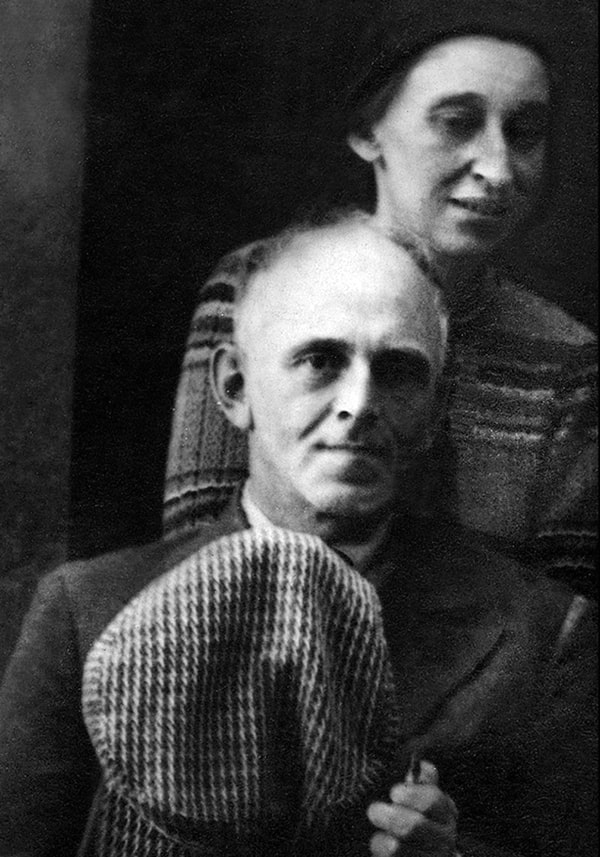

Mandelstam and his wife Nadezhda

Getty Images

Nowadays Mandelstam is considered one of the most important poets of the 20th century, although this was not always the case. During his lifetime he was in the shadow of other poets of the Silver Age – above all, Alexander Blok, according to literary historian and Mandelstam biographer Oleg Lekmanov. Then his poems were banned for many years, until the publication of We live without feeling the country beneath us helped revive interest in him.

However, the main interest in Mandelstam was fueled by two books of memoirs by his wife Nadezhda which came out in 1970. In the West, more copies of the memoirs were published than of Mandelstam’s poems. In her memoirs, she describes not only her husband’s life but also provides portraits of many of his contemporaries.

4. He was one of the most complex poets in the world

L: Mandelstam, R: Nabokov

TASS, Global Look Press

Western academics began to seriously study Mandelstam after a collection of his poetry was published in the U.S. At the time Kirill Taranovsky, a linguist and literary scholar of Russian origin and lecturer at Harvard University, formulated the term “subtext.” It means that the key to the incomprehensible passages in the poems of Mandelstam (as well as Akhmatova) lies in the texts of other poets – those of antiquity, or the French poets, or Pushkin and his contemporaries. By referring to these texts, we gain new shades of meaning.

Mandelstam has been studied a lot, but there is still no academic collection of his writings or a separate book of accounts about the poet by his contemporaries.

The greatness of Mandelstam was recognized even by Vladimir Nabokov who, despised practically everyone.

5. He wrote one of the best love poems in history

Moscow, 1933-1934. R-L: Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Maria Petrovykh, Osip’s father Emil, wife Nadezhda and brother Alexander.

Sputnik

Dear mistress of guilty glances… Great poet Anna Akhmatova described it as the “best love poem of the 20th century.”

The poem is full of the kind of subtexts mentioned above: Some find parallels in it with Biblical stories involving Mary and fish as symbols of Christ; or oriental fairy tales in which fish were metaphors for sex.

Dear mistress of guilty glances,

glum owner of narrow shoulders,

quieted by men’s dangerous dispositions

she no longer sounds, drowned speech.

Odd fish travel, flashing their fins,

gills inflated. Here, you take them,

with their silently opening mouths,

feed them the half-bread of your flesh.

We are not fish, red and golden,

our sisterly fashion is this:

thin ribs framing a warm body

and the useless, moist glow of eyes.

The brows’ arch marks a risky path.

Must I, like a janissary, love

this miniature, bird-red mouth,

your lips’ pitiful crescent month?

Don’t rail, my dear Turkish girl.

I would be sewn up with you in a sack,

your dark language I would swallow,

on fire water for you I would get drunk.

You, Maria, are an aide to the dying.

We must warn death, fall asleep.

I stand before the hard threshold.

Go away. Please, go. Stay a bit. (1934)

(Translated by Alex Cigale)

If you know Russian, watch Roman Liberov’s animated film about Mandelstam,

“Save My Speech Forever”