Leven en werk

Jeugd en studie

Andrej Tarkovski werd in 1932 geboren als oudste zoon van de Russische dichter Arseni Tarkovski. Al op jonge leeftijd raakte Tarkovski onder de indruk van het geweld van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Dit element zou later van grote invloed zijn geweest op zijn films. Zijn vader verliet het gezin reeds in 1937, maar bleef het financieel wel steunen.

Tarkovski studeerde vanaf 1951 Arabisch maar maakte deze opleiding niet af en ging in 1953 mee met een geologische expeditie naar Siberië. Toen hij daar een jaar later van terugkwam had hij besloten filmregisseur te worden en meldde zich aan bij de VGIK, de filmacademie van Moskou. Tijdens deze zesjarige opleiding maakte hij The Killers (1956) en There will be no leave today (1959). In 1960 studeerde hij af met de examenfilm De stoomwals en de viool.

Internationale erkenning

In 1962 maakte Tarkovski zijn speelfilmdebuut met De jeugd van Ivan, een psychologisch drama over een jongetje dat opgroeit in het Rusland van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. De film ging in het Westen in première op het filmfestival van Venetië en behaalde meteen de hoogste prijs: de Gouden Leeuw. De Sovjetregering was er minder over te spreken, Chroesjtsjov had na het zien van de film gezegd dat kinderen nooit zo werden ingezet in de oorlog. Dit zorgde ervoor dat de film werd doodgezwegen en een kleine roulatie kreeg.

In 1966 maakte Tarkovski een film over het leven van de middeleeuwse iconenschilder Andrej Roebljov. In deze film verwerkte Tarkovksi kritiek op het Sovjetbeleid dat kunstenaars geen vrijheid gaf. De regering was hier uiteraard niet van gediend en ze wilden alle kopieën van de film vernietigen. Enkele kopieën konden toch het land uitgesmokkeld worden en zo kwam het dat de film pas in 1969 op het filmfestival van Cannes in première ging. Daar werd de productie gelauwerd als een van de beste films aller tijden en kreeg Tarkovksi het imago van meesterregisseur toebedeeld.

In zijn eigen land werd Tarkovski echter verguisd en het was voor hem onmogelijk een nieuwe film van de grond te krijgen. Pas in 1971 maakte hij, deels gefinancierd met buitenlands geld, een volgende film, Solaris, naar het gelijknamige boek van Stanisław Lem. Dit is de meest toegankelijke en daarom de enige voor een wat groter publiek succesvolle film van Tarkovski.

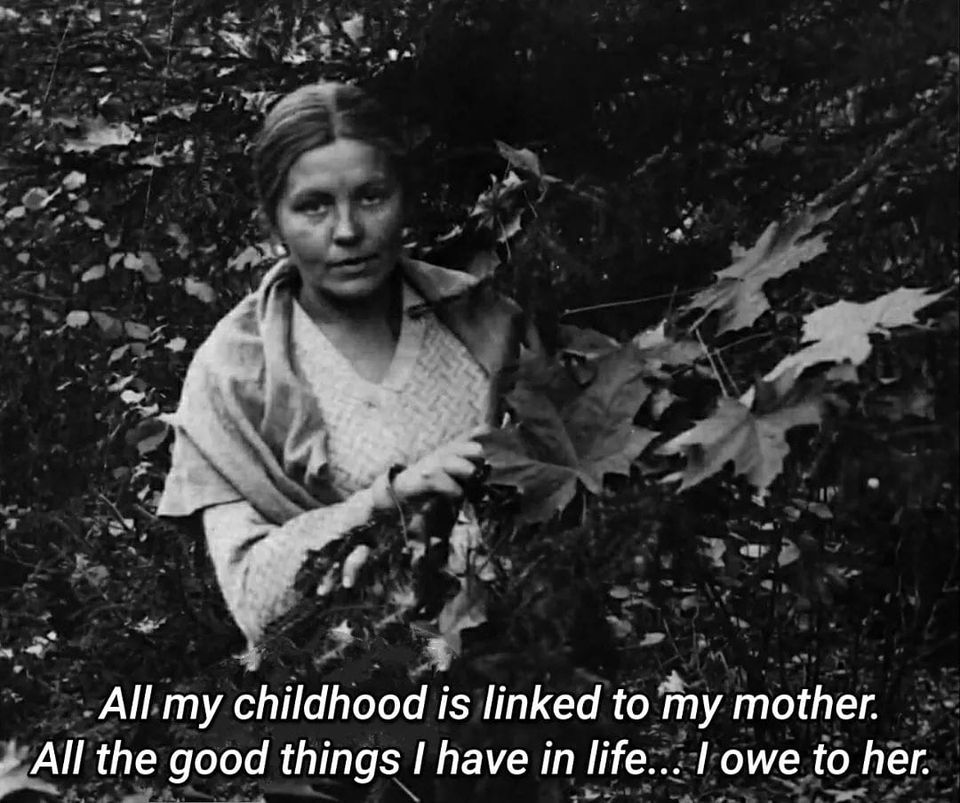

In 1975 maakte hij De spiegel, volgens veel kenners een van de origineelste en meest tegendraadse en moeilijkste films ooit. In deze film gooide Tarkovski iedere vorm van logica of plotontwikkeling overboord. Wat resteert is een reeks losse scènes die op abstracte wijze de psychologie van het hoofdpersonage laten zien. De spiegel groeide uit tot een ware filmklassieker en trok de aandacht van critici wereldwijd. De film trok ook de aandacht van de Sovjetregering, die De spiegel verbood vanwege een aantal scènes die een negatief beeld gaven van de Russische geschiedenis.

In 1977 schreef Tarkovksi zijn boek De verzegelde tijd, dat pas in 1984 werd gepubliceerd, eerst in het Duits, twee jaar later ook in het Engels en Nederlands. Hierin beschreef hij dat cinema de enige kunst is waarmee de tijd beïnvloed kan worden. Door een ultratraag tempo, langzaam bewegende shots, een extreem laag montageschema, door vervreemding van de werkelijkheid en door een vreemd gebruik van geluid, muziek, kleur, close-ups en beweging wilde Tarkovski de kijker “bedwelmen”, waardoor hij het besef van tijd kwijtraakt en zich helemaal laat meevoeren door het verhaal.

De eerste film die de “verzegelde-tijdideologie” aanhangt was Stalker uit 1979. Deze film is gebaseerd op het boek Bermtoeristen van Arkadi en Boris Stroegatski. Dit is een sciencefictionfilm die zich in de “Zone” afspeelt, een niet nader aangegeven plaats waar afstand en tijd niet gelden. De eerste opnamen werden door het laboratorium (dat in handen was van de regering) slecht behandeld en toen Tarkovski de beschadigde film zag heeft hij alles opnieuw opgenomen met een nieuwe cameraman. De film vond weinig weerstand bij de Sovjetautoriteiten en kreeg een roulatie. Het volgende jaar ging de film voor het Westen in première in Cannes.

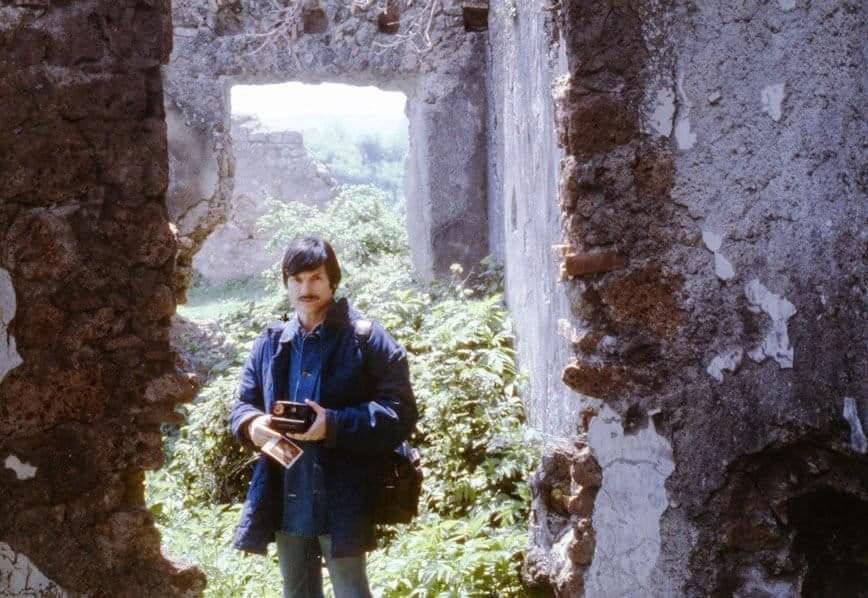

Omdat Tarkovski zo populair was in het buitenland, genoot hij voor Sovjetbegrippen een relatief grote vrijheid. Hij reisde veel in Europa en maakte in 1979 samen met scenarist Tonino Guerra de documentaire Tempo di viaggio. Met Guerra schreef Tarkovski ook het script voor Nostalghia, zijn volgende film. Na een moeizame voorbereiding ging Tarkovski in 1982 weer naar Italië voor de opnames. In 1983 was de film klaar voor het festival van Cannes. Het was wederom een groot succes. Mede door toedoen van de Russische delegatie onder leiding van Sergej Bondartsjoek won de film niet de Gouden Palm, maar kreeg een voor de gelegenheid gecreëerde prijs die hij deelde met Robert Bresson: le Grand Prix de Création.

In Zweden maakte hij in 1986 Het offer, met een ploeg die deels ook met Ingmar Bergman had gewerkt. Deze film laat het beste Tarkovski’s unieke stijl zien.

Overlijden

Tijdens het werken aan Het offer werd bij Tarkovski longkanker geconstateerd. Tarkovski werd kort voor zijn dood naar een ziekenhuis in Parijs gebracht, alwaar hij nog een paar memoires schreef. Hij overleed in 1986 en werd slechts 54 jaar.

Stijl

Zijn films zijn allemaal expressionistische psychologische drama’s waarin de gedachten en emoties van de personages door de manier van filmen en de vormgeving verteld worden. Zij zijn altijd op zoek naar de betekenis van hun leven of naar spirituele verdieping. De films zelf worden gekenmerkt door een sombere rauwe vormgeving met veel symbolen, metaforen en autobiografische elementen, maar het bijzondere is de vreemde manier van monteren en filmen. Tarkovski probeerde namelijk door lange onversneden camerashots en langzame camerabewegingen een sfeer op te wekken waarbij de kijker het gevoel van tijd kwijtraakt. Op deze manier wordt de kijker naar een hoger bewustzijn getild. Tarkovski zelf vergeleek zijn stijl met transcendente meditatie, de voortdurende herhaling van langzame shots en geluiden vervulde hierbij de functie van een soort mantra.

Al met al is Tarkovski een buitengewoon eigenzinnige regisseur. Zijn films worden dan ook gezien als moeilijke en ontoegankelijke films. Dit was dan ook de reden dat Tarkovski’s werk nooit aansloeg bij het grote publiek: velen vonden zijn films onbegrijpelijk, te lang of somber. Hierdoor werd het voor Tarkovski moeilijk om zijn projecten te financieren. Een ander probleem is dat zijn films niet in de smaak vielen bij de Sovjet-regering: zij vonden zijn “onbegrijpelijke films” gevaarlijk vanwege de politieke elementen.

Al het geldgebrek en de politieke tegenwerking ten spijt, is Tarkovski er wel in geslaagd een aantal, volgens critici, meesterlijke en tijdloze speelfilms achter te laten. Zijn intellectuele werk is nog steeds geliefd bij filmcritici, cinefielen en cultliefhebbers. Bij hen heeft Tarkovski een bijna mythische status verworven.

Net als bij bijna alle meesterregisseurs heeft ook Tarkovski, zowel qua inhoud als vorm, een herkenbare stijl. Hier volgen de belangrijkste kenmerken:

Inhoud

- de hoofdpersoon is altijd een eenzaam individu. Gedurende de film gebeurt er iets waardoor hij gaat nadenken over zijn bestaan. Hij worstelt met zichzelf, twijfelt en gaat op zoek naar spirituele verlossing. Het loopt vaak slecht met hem af. Het personage wordt vaak geplaagd door een trauma of complex.

- de films bevatten autobiografische elementen.

- de films bevatten politieke meningen, vaak in strijd met de toenmalige Sovjet-ideologie.

- centraal thema in al z’n werk is de overlevingsdrang van de mens en de wil van de creatieve geest.

- in al z’n films staat spiritualiteit centraal.

- het verhaal is meestal vrij simpel en rechtlijnig en wordt verteld aan de hand van metaforen en andere symboliek.

Vormgeving

- de films zijn minimalistisch, dus met zo min mogelijk beelden zo veel mogelijk vertellen. De kijker moet het verhaal uit de beelden halen. Zo veel mogelijk suggestie.

- de films zijn expressionistisch: de emoties en gevoelens worden door de vormgeving, de symboliek en de manier van filmen verteld.

- dromen en flashbacks komen veelvuldig voor.

- “verzegelde-tijdstijl” van filmen.

- de films spelen zich af op onduidelijke locaties.

- geen duidelijke tijdsaanduiding.

- de films zijn deels in kleur, deels in zwart/wit.

- vervreemding van de werkelijkheid.

- extreme close-ups van emotionele gezichten en van subtiele schoonheid, zoals regendruppels, rimpels in het water, bladeren die bewegen in de wind, barsten in een stenen muur, enzovoorts.

- shots kunnen erg lang duren: de scene van Gortsjakov met de kaars in Nostalghia is één shot van 9 minuten en 7 seconden.

- de films staan bekend om een fascinatie voor de natuur. Landschappen zijn vaak het decor van veel van z’n films: ze symboliseren de emoties en gedachten van de hoofdpersonen. Ook komen de vier elementen van de natuur: water, vuur, lucht (in de gedaante van wind) en aarde veelvuldig voor.

Filmografie

- De doders, kortfilm (1956) naar een verhaal van Ernest Hemingway (Убийцы)

- De stoomwals en de viool (1960) (Каток и скрипка)

- De jeugd van Ivan (1962) (Иваново детство)

- Andrej Roebljov (1966) (Андрей Рублёв)

- Solaris (1972) (Солярис)

- De spiegel (1974) (Зеркало)

- Stalker (1979) (Сталкер)

- Nostalghia (1983)

- Het offer (1986) (Offret) https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrej_Tarkovski

Anatoly Alekseyevich Solonitsyn (Anatoli, Anatoliy; Russian: Анатолий (Отто) Алексеевич Солоницын; 30 August 1934 – 11 June 1982 in Moscow) was a Soviet and Russian actor known for his roles in Andrei Tarkovsky’s films. He won the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the 31st Berlin International Film Festival.

Solonitsyn was born in Bogorodsk. At birth, he was named Otto, after polar explorer Otto Schmidt, but later changed his German name to Anatoly.

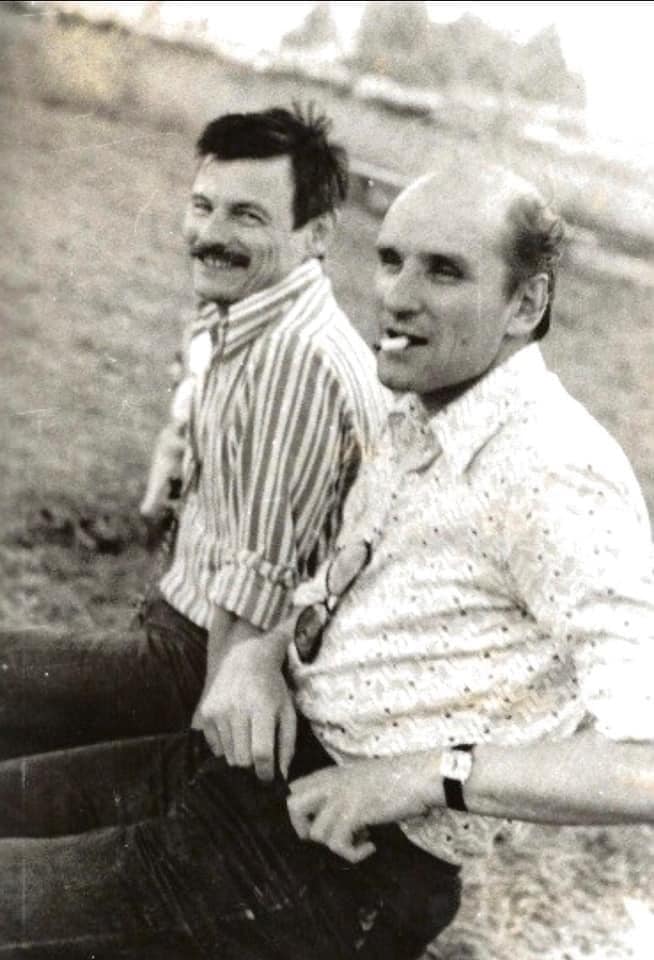

His debut in cinema was in the Sverdlovsk Film Studio’s short film The Case of Kurt Clausewitz (1963), directed by Gleb Panfilov. Solonitsyn is best known in the west for his roles in several of Andrei Tarkovsky‘s films, including Dr. Sartorius in Solaris (1972), the Writer in Stalker (1979), the physician in Mirror (1975), and the title role in Andrei Rublev (1966). Indeed, it was Tarkovsky who “discovered” him in the casting process for Andrei Rublev. Solonitsyn was an unknown provincial theater actor from Sverdlovsk at the time, but he took the opportunity to go to Moscow and try himself in the casting for the Andrei Rublev role. Historical consultant of the movie saw the photos of actors from the casting, pointed to a photo of Solonitsyn and said to Tarkovsky: “This one is Rublev”.

In his book Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky calls him his “favorite” actor, and writes that Solonitsyn was intended to play the lead roles in each of his films Nostalghia (1983) and The Sacrifice (1986), but the actor died before their production. Tarkovsky admired Solonitsyn’s ability to fully embody the ideas of the director. When Tarkovsky was considering making a film adaptation of Dostoevsky’s famous novel The Idiot, Solonitsyn was even ready to do the plastic surgery to look more like the iconic Russian writer.

In the former Soviet Union he is also well known for his roles in At Home Among Strangers (1974), The Train Has Stopped (1982), and many others.

Awards

In 1981, he won the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the 31st Berlin International Film Festival for his role in Aleksandr Zarkhi‘s film Twenty Six Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky. The same year, he was given the title of Honored Artist of the RSFSR.

Death

Solonitsyn died from cancer in 1982, at the age of 47. Allegedly, according to Viktor Sharun, the sound editor on Stalker, Solonitsyn, Tarkovsky and Larisa Tarkovskaya became ill due to exposure to toxic chemicals during filming on the location of the movie.

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Andrei Rublev | Andrei Rublev | |

| 1968 | Anyutyna doroga | Stepan | |

| 1968 | No Path Through Fire | Ivan Yevstryukov | |

| 1969 | Odin shans iz tysyachi | kapitan Migunko | |

| 1971 | Trial on the Road | (segment Kolovert’) | |

| 1972 | Solaris | Dr. Sartorius, astrobiologist | |

| 1973 | Lyubit cheloveka | Dmitri Kalmykov | |

| 1973 | Grossmeyster | ||

| 1973 | Zarubki na pamyat | Romus Cherbanu | |

| 1974 | Under en steinhimmel | Hoffmeyer, oberst | |

| 1974 | Agony | Colonel | |

| 1974 | At Home Among Strangers | Sarychev | |

| 1974 | Posledniy den zimy | ||

| 1975 | Mirror | Forensic doctor | |

| 1975 | Vozdukhoplavatel | Aviation School Head Henri Farman | |

| 1975 | Tam, za gorizontom | ||

| 1975 | Mezhdu nebom i zemlyoy | Orlov | |

| 1976 | Doverie | Bochazhnikov | |

| 1977 | The Ascent | Portnov, the Nazi interrogator | |

| 1977 | Legenda o Tile | Fishman | |

| 1978 | Yuliya Vrevskaya | ||

| 1978 | A u nas byla tishina… | Petrukha | |

| 1978 | Predveshchayet pobedu | Viktor Vershinin | |

| 1979 | Trassa | ||

| 1979 | Bag of the Collector | Ivan Timofeyevich | |

| 1979 | Povorot | Kostantin Korolyev | |

| 1979 | Stalker | Writer | |

| 1979 | The Bodyguard | Sultan-Nazar | |

| 1980 | Sergey Ivanovich ukhodit na pensiyu | Vladimir Vasilyevich | |

| 1981 | Twenty Six Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky | Fyodor Dostoevsky | |

| 1981 | Tainstvennyy starik | Kondratiy | |

| 1981 | Rasputin | Colonel | |

| 1981 | Tayna zapisnoy knizhki | Martyn Martynych | |

| 1981 | Raskidannoye gnezdo | Wanderer | |

| 1981 | Muzhiki! | Painter | |

| 1981 | Iz zhizni otdykhayushchikh | Tolik Chikin | |

| 1982 | Ostanovilsya poezd | Malinin, a journalist | |

| 1982 | Shlyapa | ||

| 1986 | Proverka na dorogakh | Igor Leonidovich Petushkov | (final film role) |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatoly_Solonitsyn

The Sacrifice (Swedish: Offret) is a 1986 drama film written and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Starring Erland Josephson, it centers on a middle-aged intellectual who attempts to bargain with God to stop an impending nuclear holocaust. The Sacrifice was Tarkovsky’s third film as a Soviet expatriate, after Nostalghia and the documentary Voyage in Time, and was also his last, as he died shortly after its completion. Like 1972’s Solaris, it won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival.

Plot

The film opens on the birthday of Alexander (Erland Josephson), an actor who gave up the stage to work as a journalist, critic and lecturer on aesthetics. He lives in a beautiful house with his actress wife Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), stepdaughter Marta (Filippa Franzén), and young son, “Little Man”, who is temporarily mute due to a throat operation. Alexander and Little Man plant a tree by the seaside, when Alexander’s friend Otto, a part-time postman, delivers a birthday card to him. When Otto asks, Alexander says his relationship with God is “nonexistent”. After Otto leaves, Adelaide and Victor, a medical doctor and a close family friend who performed Little Man’s operation, arrive and offer to take Alexander and Little Man home in Victor’s car, but Alexander prefers to stay behind and talk to his son. In his monologue, he first recounts how he and Adelaide found their house near the sea by accident, and how they fell in love with it and its surroundings, but then enters a bitter tirade against the state of modern man. As Tarkovsky wrote, Alexander is weary of “the pressures of change, the discord in his family, and his instinctive sense of the threat posed by the relentless march of technology”; in fact, he has “grown to hate the emptiness of human speech”.

The family, Victor, and Otto gather at Alexander’s house for the celebration. Their maid Maria leaves, while nurse-maid Julia stays to help with the dinner. People comment on Maria’s odd behavior. The guests chat inside the house, where Otto reveals that he is a student of paranormal phenomena, a collector of “inexplicable but true incidents.” Just when dinner is almost ready, the rumbling noise of low-flying jet fighters interrupts them, and soon after, as Alexander enters, a news program announces the beginning of what appears to be all-out war, and possibly nuclear holocaust. His wife has a complete nervous breakdown. In despair, Alexander vows to God to renounce all he loves, even Little Man, if this may be undone. Otto advises him to slip away and lie with Maria, who Otto tells him is a witch “in the best possible sense”. Alexander takes a pistol from Victor’s medical bag, leaves a note in his room, escapes the house, and rides Otto’s bike to Maria’s house. She is bewildered when he makes his advances, but when he puts the gun to his temple (“Don’t kill us, Maria”), at which point the jet-fighters’ rumblings return, she soothes him and they make love while floating above her bed, though Alexander’s reaction is ambiguous.

When he wakes the next morning, in his own bed, everything seems normal. Nevertheless, Alexander sets forth to give up all he loves and possesses. He tricks the family members and friends into going for a walk, and sets fire to their house while they are away. As the group rushes back, alarmed by the fire, Alexander confesses that he set it, and runs around wildly. Maria, who until then was not seen that morning, appears; Alexander tries to approach her, but is restrained by others. Without explanation, an ambulance appears, and two paramedics chase Alexander, who appears to have lost control of himself, and drive off with him. Maria begins to bicycle away, but stops to observe Little Man watering the tree he and Alexander planted the day before. As Maria leaves, the “mute” Little Man, lying at the foot of the tree, speaks his only line, which quotes the opening of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word. Why is that, Papa?”

Cast

- Erland Josephson as Alexander

- Susan Fleetwood as Adelaide

- Allan Edwall as Otto

- Guðrún Gísladóttir as Maria

- Sven Wollter as Victor

- Valérie Mairesse as Julia

- Filippa Franzén as Marta

- Tommy Kjellqvist as Gossen (Little Man)

- Per Källman, Tommy Nordahl as ambulance drivers

Production

Pre-production

The Sacrifice originated as a screenplay called The Witch, which preserved the element of a middle-aged protagonist spending the night with a reputed witch. But in this story, his cancer was miraculously cured, and he ran away with the woman. In March 1982, Tarkovsky wrote in his journal that he considered this ending “weak”, as the happy ending was unchallenged He wanted personal favorite and frequent collaborator Anatoly Solonitsyn to star in this picture, as was also his intention for Nostalghia, but when Solonitsyn died from cancer in 1982, the director rewrote the screenplay into what became The Sacrifice and also filmed Nostalghia with Oleg Yankovsky as the lead.

Tarkovsky considered The Sacrifice different from his earlier films because, while his recent films had been “impressionistic in structure”, in this case he not only “aimed…to develop [its] episodes in the light of my own experience and of the rules of dramatic structure”, but also to “[build] the picture into a poetic whole in which all the episodes were harmoniously linked”, and because of this, it “took on the form of a poetic parable”.[3][n 3]

At the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, Tarkovsky was invited to film in Sweden, as he was a longtime friend of Anna-Lena Wibom of the Swedish Film Institute. He decided to film The Sacrifice with Erland Josephson, who was best known for his work with Ingmar Bergman, and whom Tarkovsky had directed in Nostalghia. Cinematographer Sven Nykvist, a friend of Josephson and frequent collaborator with Bergman, was asked to join the production. Despite a contemporaneous offer to shoot Sydney Pollack‘s Out of Africa, Nykvist later said it was “not a difficult choice”, and like Josephson, he became a co-producer when he invested his fees back into the film. Production designer Anna Asp, who worked on Bergman’s Autumn Sonata and After the Rehearsal and had won an Academy Award for Fanny and Alexander, also joined the project, as well as Daniel Bergman, one of Ingmar’s children, who worked as a camera assistant. Many critics commented on The Sacrifice in the context of Bergman’s work.

Filming

While often[13][14][15] erroneously claimed to have been shot on Fårö, The Sacrifice was actually filmed at Närsholmen on the nearby island of Gotland; the Swedish military denied Tarkovsky access to Fårö.

Alexander’s house, built for the production, was to be burned for the climactic scene, in which Alexander burns it and his possessions. The shot was very difficult to achieve, and the first failed attempt was, according to Tarkovsky, the only problem during shooting. Despite Nykvist’s protest, only one camera was used, and while shooting the burning house, the camera jammed and the footage was thus ruined.

The scene had to be reshot, requiring a very costly reconstruction of the house in two weeks. This time, two cameras were set up on tracks, running parallel to each other. The footage in the final version of the film is the second take, which lasts six minutes (and ends abruptly because the camera had run through an entire reel). The cast and crew broke down in tears after the take was completed.

Music

The film opens and closes with the aria “Erbarme dich, mein Gott” (“Have mercy, my God”) from Johann Sebastian Bach‘s St Matthew Passion. The soundtrack also features shakuhachi recordings by Watazumido-Shuso.

Post-production

Tarkovsky and Nykvist performed significant amounts of color reduction on select scenes. According to Nykvist, almost 60% of the color was removed from them.

Reception

The film won Tarkovsky his second Grand Prix, after Solaris, his third FIPRESCI Prize at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival, and his third Palme D’Or nomination. The Sacrifice also won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. At the 22nd Guldbagge Awards, the film won the awards for Best Film and Best Actor (Erland Josephson). In 1988, it won the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film was selected as the Swedish entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 59th Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.

Since its release, reviewers have responded positively to the film; the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports an approval rating of 86%, based on 42 reviews with an average rating of 7.58/10. The website’s critical consensus states, “Formally impressive, visually accomplished, and narratively rewarding, The Sacrifice places a fittingly solid capstone on a brilliant filmmaking career”.

In 1995, the Vatican compiled a list of 45 “great films”, separated into the categories of Religion, Values, and Art, to recognize the centennial of cinema. The Sacrifice was included in the first category, as was Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev.

Critics have commented on The Sacrifice’s religious ambiguities. Dennis Lim wrote that it is “not exactly a simple allegory of Christian atonement and self-sacrifice”. Catholic film critic Steven Greydanus contrasts the film’s “dialectic of Christian and pagan ideas” with Andrei Rublev, writing that, while Rublev “[rejects] the advances of an alluring pagan witch as incompatible with Christian love”, The Sacrifice “juxtaposes” both sensibilities. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/The_Sacrifice_(1986_film)

The Cinematography of The Sacrifice (Offret)

A video showcasing the stunning cinematography by the Swedish dop Sven Nykvist, in the final film of the Russian filmmaking master Andrei Tarkovsky.

Synopsis:

Alexander, a journalist, philosopher and retired actor, celebrates a birthday with friends and family when it is announced that nuclear war has begun.

Initial Release: 1986