‘Een rosse grutto kan non-stop van Alaska naar Nieuw Zeeland vliegen en weegt maar 500 gram. Er is geen robot die daar ook maar bij in de buurt komt.’david lentink

Als kind bouwde David Lentink eindeloos veel modelvliegtuigjes. School leek hem weinig te interesseren, maar hij was des te meer gefascineerd door de kunst van vliegen. Hoe doen vogels dat? Als bio-mechanisch ingenieur heeft hij de link gelegd tussen het vliegen van vogels en robotica. David heeft een uniek lab vol windtunnels en lasers opgezet op de prestigieuze Stanford University. Daar onderzoekt hij samen met een groep van elf promovendi nauwkeurig hoe kolibries en muspapegaaien vliegen.

‘Ik focus op vogels omdat ik die op dit moment het meest interessant vind,’ zegt hij, ‘maar ik heb ook aan insecten, vleermuizen en vliegende zaden onderzoek gedaan. Wat betreft technisch ontwerp van robots en vliegtuigen richt ik me op het hele systeem, alle aspecten hebben mijn interesse. Het vakgebied waar ik voornamelijk in werk omvat alle vormen van beweging in de natuur, zoals vliegen, zwemmen en rennen, en ook op de biologie geïnspireerde technologie, zoals de robotica.’

carrière

David Lentink (1975) is via het lbo, de mavo, de havo en zijn propedeuse HTS Vliegtuigbouw uiteindelijk bij de Technische Universiteit Delft beland. Hier heeft hij zowel zijn bachelor als master Aerospace Engineering behaald. Vervolgens promoveerde hij in Wageningen in de Experimentele Zoölogie. Nu heeft zijn eigen lab aan de prestigieuze Stanford University in Californië: het BIRD Lab. Dat is een afkorting die staat voor Bio-Inspired Research & Design. Hier worden vliegende dieren bestudeerd om luchtwaardiger robots te bouwen. In 2010 heeft hij met zijn project Vliegkunstenaars de academische jaarprijs gewonnen. Zijn unieke en innovatieve onderzoek heeft op de covers van de wetenschapstijdschriften Science en Nature gestaan.

Drie boekentips van David Lentink

- De Simpele Wetten van de Vliegkunst – Henk Tennekes (1992)

‘Het leukste en meest informatieve boek dat ik kan aanraden voor iedereen die geïnteresseerd is in vliegen vanuit het perspectief van de techneut. Vliegen is inderdaad simpel, maar ook complex. Om de complexiteit te waarderen helpt het om eerst de simpele wetten van Henk te leren: van libel en grutto tot Boeing 747, ze vallen allemaal op een lijn als ze voorwaarts op optimale snelheid vliegen.’ - Hoe vogels vliegen – John Videler (2012)

‘Dit boek geeft het breedste biologische overzicht over hoe vogels vliegen en benadrukt juist de complexiteit en wat we allemaal niet weten. Het is het perspectief van de bioloog. Het meest inspirerend voor mij is de biologische kennis die hij in zijn boeken samenbundelt tot een goed leesbaar verhaal.’

- The Wright Brothers – David McCullough (2015)

‘Als Engels geen bezwaar is leest dit heerlijk weg, want laten we eerlijk zijn, zowel techneuten als biologen kunnen niet tippen aan een echte schrijver als het gaat om het vertellen van een verhaal. McCullough bescrhijft meesleepend hoe ze het eerste gemotoriseerde en bestuurbare vliegtuig de lucht in kregen. Het gaat ook over hoe het geïnspireerd is op het werkt van de Duitser Otto Lilienthal, hun eigen inventiviteit, en eindeloos kijken naar hoe vogels vliegen. Orville Wright zei hierover “Learning the secret of flight from a bird was a good deal like learning the secret of magic from a magician” wat het motto is dat in mijn lab op de muur staat geschreven. Nu ben ik overigens de bejubeling van de “Amerikaanse uitvinding van het vliegen” zelf eigenlijk een beetje beu, want Otto Lilienthal vloog al tweeduizend keer succesvol met zijn zweefvliegtuig vele jaren voordat de Wright Brothers hun eerste zweefvlucht maakten. Helaas, niemand die daar een goed boek over schrijft dat de wereld over gaat, dus we zijn het collectief vergeten. Maar als je het Amerikaanse successausje wegdenkt, dan hou je een enorm cool verhaal over van twee fietsenmakers die een onwaarschijnlijke stap voorwaarts hebben gemaakt, door slim en inventief te denken zonder de belemmering van een academische opleiding. Het laat maar weer eens zien dat iedereen aan wetenschap en techniek kan bijdragen.’ https://www.vpro.nl/programmas/grote-vragen/bij-aflevering-3/wie-is-david-lentink.html

- Associate Professor 2021-present, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen.

- Assistant Professor 2012-2020, Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University.

- Assistant Professor 2009-2011, Experimental Zoology, Wageningen University.

- Postdoc 2009-2010, Organismal and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University.

- PhD cum laude 2008, Experimental Zoology, Wageningen University.

- MS 2003, Aerospace Engineering, Delft University of Technology.

- BS 2003, Aerospace Engineering, Delft University of Technology.

Awards

- Inaugural Steven Vogel Young Investigator Award, Journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics (2018).

- National Academy of Engineering Gilbreth Lecturer (2017).

- NSF CAREER Award (2016).

- Recognized as one of 40 scientists under 40 by the World Economic Forum (2013).

- Awardee Human Frontiers Science Program Grant (2013).

- Winner 100kE Dutch Academic Year Prize 2010.

- Finalist International Science and Engineering Visualization Challenge (2010).

- Publication prize Animal Sciences Group, Wageningen University (2010).

- Biophysics thesis award, Dutch Society for Biophysics and Biomedical Technology (2009).

- Zoology Award, Royal Dutch Zoological Society (2009).

- Finalist Dutch National Aeronautical Award (2009).

- Bolk Prize, Netherlands Society for Anatomy (2008).

- Publication prize, WIAS graduate school (2008).

- Best PhD presentation, WIAS Science Day (2007).

- Elsevier Young Scientist Award, Society for Experimental Biology (2005).

- Best PhD presentation, BeNeLux Zoology conference (2005).

- AIAA best fluid dynamics conference paper award 2003 (2004).

- Prof. Dobbinga Award Delft University of Technology (2003). https://www.rug.nl/staff/d.lentink/cv?lang=en

Oh My Godwit – The Longest Bird Migration in the World

Tientallen camera- en natuurliefhebbers volgden het afgelopen jaar een cursus high speed filmen bij David Lentink. Dit leverde honderden filmpjes op van het vliegend leven in Nederland.

There’s so little we understand about how birds fly. Through incredible photography and observations in his lab’s wind tunnel, engineering professor David Lentink highlights rarely detected bird behavior. By studying nature, his lab seeks to build better drones. David Lentink is an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and member of Bio-X, an interdisciplinary biosciences institute at Stanford. Professor Lentink’s multidisciplinary lab studies biological flight—bird flight in particular—as an inspiration for engineering design. He serves as a member of the Young Academy of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and received the Dutch Academic Year Prize for the Flight Artists, in which Professor Lentink crowdsourced high-speed camera footage to capture flight movements. In 2013, the World Economic Forum named him one of 40 scientists under 40. His publications range from technical journals to cover publications in Nature and Science. This Stanford+Connects micro lecture was filmed on location in Washington, DC. Stanford+Connects is a program of the Stanford Alumni Association. Watch, learn and connect: https://stanfordconnects.stanford.edu/

The Magic of Bird Flight with David Lentink

TEDxAmsterdam 2011 – David Lentink

De napraatsessie van Labyrint over de vliegkunstenaars. David Lentink, een team wetenschappers en een nog grotere groep enthousiaste amateurfilmers hebben met een hogesnelheidscamera beelden gemaakt van vogels en insecten. Door hun bewegingen vertraagd te bestuderen, hoopt Lentink meer te leren over hoe deze dieren vliegen en waarom. Presentatie: Eef Grob De uitzending van labyrint over de vliegkunstenaars werd op 11 januari 2012 uitgezonden en is terug te kijken via de website. www.wetenschap24.nl www.labyrint.nl

David Lentink: We want to fly anywhere, regardless of turbulence

Lentink is known for his work on aerial vehicles that are inspired by birds, bats and flying insects.March 4, 2019

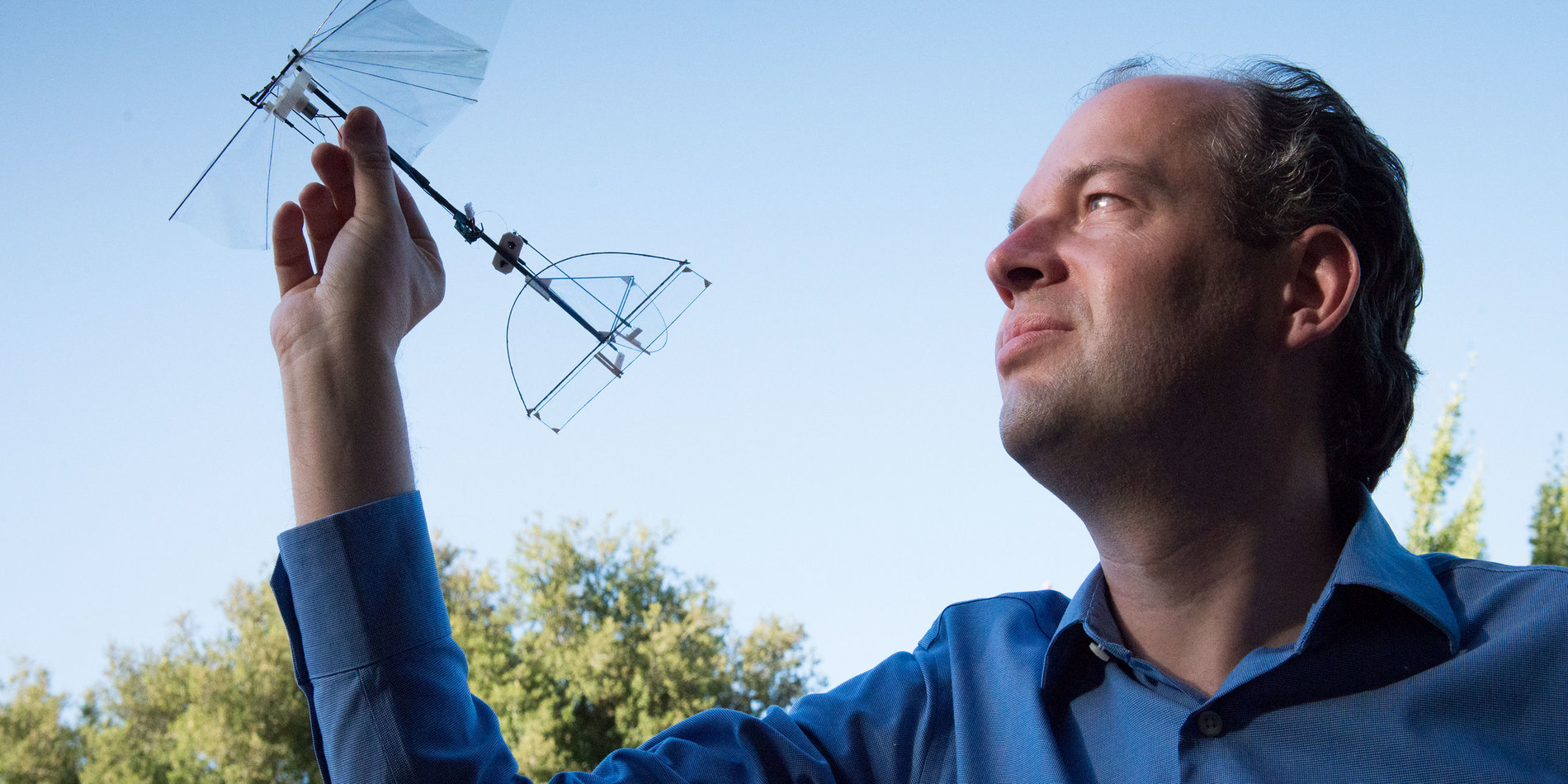

Lentink holds an example of the models his students are making to simulate birds in flight. | Photo credit: L.A. Cicero

What inspired you to take an interest in robots?

I designed and built model airplanes at high school and set flight duration records in competition. The rubber-powered airplanes I designed then were passively stable — they had to fly on their own without any computer onboard — so the design had to be just right. They could fly up to 18 minutes on a single rubber band. (I did not compete in world championships, but plan to pick it up again when I am 70 years old, because that is the ideal age to become world champion in it!)

I also started building flapping model airplanes powered by rubber bands. From this hobby, I learned robots could do so much more if you build in the dynamics that they need to perform well passively. Then you can focus the limited onboard control on what matters most to complete a mission.

This lesson has proven a real advantage because I don’t get bogged down by dogmas requiring impossible computational power. It has also helped me question the conventional wisdom that unstable aerial robots that are constantly controlled by an autopilot are most maneuverable. More important, the instability of robots may be a key factor that is limiting them from flying well in turbulence, such as gusts of wind in urban environments.

What was your first robotics project?

My first project was the DelFly project, which I initiated as a PhD student in Delft based on my aerodynamics research of insect flight at Caltech. I discovered that insect aerodynamics was scalable to the scale of robots, which meant I could use standard motors, batteries and radio control components and make robots fly like insects for a couple thousand dollars instead of a million. (This is what people were spending on it in 2005, without success.)

My team, which included 10 undergraduates, and I worked on a flapping robot that could vertically take off and land like an insect many times. It was based on the world’s worst actuators and remote control electronics, because everything had to be tiny and lightweight. The design was way too slow and imprecise for such a dynamic maneuver in the books of a control’s engineer. Thanks to the well-designed passive dynamics, the robot could pull off a vertical take-off and landing maneuver as many times as we liked — as many as 19 times in one video.

Along the way I had to convince the students to ignore all the advice on making the robot unstable, which they received from control’s engineers work based on aircraft design. To succeed, you have to find ways to cope with the many paradigms in different fields and shift them one by one.

Thinking back, what did you hope robots would be doing in the “future”?

When I first was getting into the aerial robotics, I was hoping we could fly like animals do. I was fascinated by how birds fly and maneuver in a fashion that seemed effortless. For example, I asked my professor at Delft if he knew why my ornithopters did not need a vertical tail — same as birds and insects — and he didn’t know. He said it would be a great research question. (Now, a student in my lab measured it this past summer and we much better understand than when I started as a student.)

As a student, I was also inspired by the amazing stop-motion photos of insects and birds made by Stephen Dalton and John Brackenbury. Whereas the birds in flight were instantly appealing to me, the photos of the insects transformed my thinking. I still don’t like insects, but insects in flight look incredible; they are like beautiful aerial ballet dancers with their wings spread, generating lift and thrust. It inspired me to develop insect-inspired robots with students.

But I always craved going back to birds. They are less accessible to engineers — and rightfully so — due to additional levels of regulations for working with vertebrates. So, after my BS and MS in aerospace engineering, I became a biologist during my PhD. As an engineer and biologist I can study birds up close with my students and use that inspiration to design aerial robots that fly like birds.

Now, I am excited about the economic potential of aerial robot delivery. I do think some company will transform the way we move goods around the planet and deliver them rapidly and efficiently and I think that will serve our economy well.

My other passion is the potential of aerial robots to perform search and rescue during natural disasters. Current drones cannot meet that challenge — they are still too unsafe, too noisy and fly too short of distances. Weather, especially precipitation and turbulent gusts, are open challenges. That is why I study birds — they outperform aerial robots with a large margin and can fly most of the time. For example, the 300-gram bar-tailed godwit can fly 11,700 km from Alaska to New Zealand and the 40-gram common swift can fly without landing for nine months, catching insects, scooping water and sleeping on the wing.

What are you working on now related to robotics?

With my lab, I am studying how birds fly and, integrating our findings, we are developing better flying autonomous robots. Our biggest current effort is to make robots fly better in turbulence.

I also collaborate with Mark Cutkosky and a student we co-advise, Will Roderick, on new passive mechanisms to enable robots to perch on a wide range of natural surfaces. Basically, we want to fly anywhere and land anywhere, regardless of turbulence and regardless of the complexity of perching surfaces. Both these aerial robot performance aspects are essential for efficient aerial delivery and search and rescue.

Ever since my DelFly, I have further pursued learning deeply in many areas to accomplish something new and unexpected. Like developing a $10,000 robot with undergraduates that outperforms all the expensive ones developed by PhD students, postdocs and experienced engineers. A big part of the success comes from students believing they can do anything and them not being bogged down by too much knowledge.

How have the big-picture goals or trends of robotics changed in the time that you’ve been in this field?

I have largely avoided following trends because so many of them are focused on short-term advances. Also, by defining our own area of research we can focus more on collaborating with other labs instead of competing.

Currently, I have the only engineering lab with a bird wind tunnel to decipher the physical mechanisms that enable birds to outperform aerial robots. It is next-level bio-inspired design, because my engineers understand both the biology and the aerial robot application.

All our work is interdisciplinary and that is something we see more and more in other labs. I really like our high level of integration and collaboration in the lab because I think a PhD is best done together. My students are all experts in different areas and, in their joint office, they sit and talk with experts in other areas. This group culture has enabled each of them to pursue work they could have never accomplished as well on their own.

We learn a ton together and make frequent discoveries about how birds fly to build these new robots, which usually inspire new questions. It is a passionate cycle of scientific discovery and invention. Thanks to my students I am engaged in several areas of research at the deepest level too. It is what I am in research for. I love learning new stuff and making discoveries together. https://engineering.stanford.edu/magazine/article/david-lentink-we-want-fly-anywhere-regardless-turbulence?fbclid=IwAR2rQzRVcYGqzq47vsimt4FuEGPq5e8tUw4UVARFELP3P4RuwTptlwNiKGk

Bert Snijder 🙂