Murdoch’s £1m Bill for hiding dirty tricks

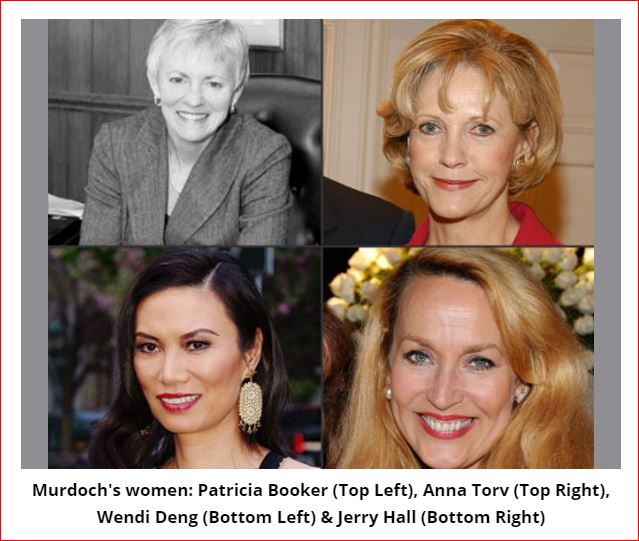

Media mogul Murdoch has been married four times and has had six children in total. His first marriage was to flight attendant Patricia Brooker in 1956. The couple had one child, Prudence, in 1958 and divorced in 1967.

The same year he divorced Patricia, Murdoch married journalist and novelist Anna Torv (now Mann), who was born in Scotland and is 13 years his junior.

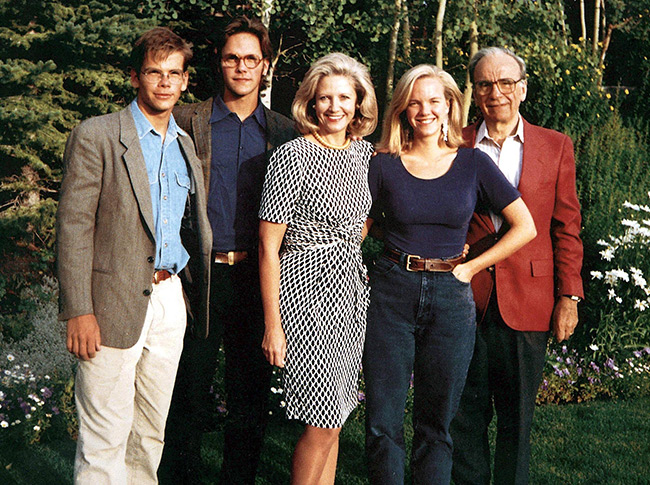

Mann and Murdoch had three children together while they were married: Elisabeth Murdoch (born 1968), Lachlan Murdoch (born 1971), and James Murdoch, (born 1972).

The couple were divorced in 1999, with Mann, now 76, going on to marry financier William Mann six months later. The two are still together. Wendi Deng 17 days after Murdoch and Mann divorced, he married Chinese-born American entrepreneur and media mogul Wendi Deng.

Murdoch’s marriage to Deng, who is now 51 and is 37 years younger than Murdoch, lasted until 2013.

During their time together, they had two children: Grace (born 2001) and Chloe (born 2003).

Murdoch, now 89, married model and actor Jerry Hall, 64, in 2016.

Their engagement was announced four months after their relationship was made public.

The pair don’t share any children.

De 84-jarige mediamagnaat Rupert Murdoch stapt voor de vierde keer in het huwelijksbootje. Deze keer is actrice en fotomodel Jerry Hall (59) de gelukkige. Zij is de ex-partner van Rolling Stones-voorman Mick Jagger.

The Guardian, July 9 2009

The news story which kicked off the scandal

Rupert Murdoch’s News Group Newspapers has paid out more than £1m to settle legal cases that threatened to reveal evidence of his journalists’ repeated involvement in the use of criminal methods to get stories.

The payments secured secrecy over out-of-court settlements in three cases that threatened to expose evidence of Murdoch journalists using private investigators to illegally hack into the mobile phone messages of numerous public figures and to gain unlawful access to confidential personal data, including tax records, social security files, bank statements and itemised phone bills. Cabinet ministers, MPs, actors and sports stars were all targets of the private investigators.

Today, the Guardian reveals details of the suppressed evidence, which may open the door to hundreds more legal actions by victims of News Group, the Murdoch company that publishes the News of the World and the Sun, as well as provoking police inquiries into reporters who were involved and the senior executives responsible for them. The evidence also poses difficult questions for:

- Conservative leader David Cameron’s director of communications, Andy Coulson, who was deputy editor and then editor of the News of the World when, the suppressed evidence shows, journalists for whom he was responsible were engaging in hundreds of apparently illegal acts.

- Murdoch executives who, albeit in good faith, misled a parliamentary select committee, the Press Complaints Commission and the public.

- The Metropolitan police, which did not alert all those whose phones were targeted, and the Crown Prosecution Service, which did not pursue all possible charges against News Group personnel.

- The Press Complaints Commission, which claimed to have conducted an investigation but failed to uncover any evidence of illegal activity.

The suppressed legal cases are linked to the jailing in January 2007 of a News of the World reporter, Clive Goodman, for hacking into the mobile phones of three royal staff, an offence under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act. At the time, News International said it knew of no other journalist who was involved in hacking phones and that Goodman had acted without their knowledge.

But one senior source at the Met told the Guardian that during the Goodman inquiry, officers found evidence of News Group staff using private investigators who hacked into “thousands” of mobile phones. Another source with direct knowledge of the police findings put the figure at “two or three thousand” mobiles. They suggest that MPs from all three parties and cabinet ministers, including former deputy prime minister John Prescott and former culture secretary Tessa Jowell, were among the targets.

Last night, Prescott said: “I think Mr Cameron should be thinking of getting rid of Coulson.”

News International has always maintained it had no knowledge of phone hacking by anybody acting on its behalf.

Murdoch told Bloomberg news last night that he knew nothing about the payments. “If that had happened I would know about it,” he said.

A private investigator who had worked for News Group, Glenn Mulcaire, was also jailed in January 2007. In addition to the three royal staff, he admitted hacking into the phones of five other targets, including the chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association, Gordon Taylor; the Lib Dem MP Simon Hughes; celebrity PR Max Clifford; model Elle MacPherson; and football agent Sky Andrew. News Group denied all knowledge of the hacking, but Gordon Taylor last year sued them on the basis that they must have known about it.

In documents initially submitted to the high court, News Group executives said the company had not been involved in any way in Mulcaire’s hacking of Taylor’s phone. They denied keeping any recording or notes of intercepted messages. But, at the request of Taylor’s lawyers, the court ordered the production of detailed evidence from Scotland Yard’s inquiry in the Goodman case, and from an inquiry by the information commissioner into journalists who dishonestly obtain confidential personal records.

The Scotland Yard files included paperwork which revealed that, contrary to News Group’s denial, Mulcaire had provided a recording of the messages on Taylor’s phone to a News of the World journalist who had transcribed them and emailed them to a senior reporter; and that a News of the World executive had offered Mulcaire a substantial bonus for a story specifically related to the intercepted messages. Several famous figures in football are among those whose messages were intercepted.

Andy Coulson was editing the paper at this time. He said last night: “This story relates to an alleged payment made after I left the News of the World two and half years ago. I have no knowledge whatsoever of any settlement with Gordon Taylor.

“The Mulcaire case was investigated thoroughly by the police and by the Press Complaints Commission. I took full responsibility at the time for what happened on my watch but without my knowledge and resigned.”

The paperwork from the Information Commission revealed the names of 31 journalists working for the News of the World and the Sun, together with the details of government agencies, banks, phone companies and others who were conned into handing over confidential information. This is an offence under the Data Protection Act unless it is justified by public interest.

Senior editors are among those implicated. This activity occurred before the mobile phone hacking, at a time when Coulson was deputy and the editor was Rebekah Wade, now due to become chief executive of News International. The extent of their personal knowledge, if any, is not clear: the News of the World has always insisted that it would not break the law and would use subterfuge only if essential in the public interest.

Faced with this evidence, News International changed their position, started offering huge cash payments to settle the case out of court, and finally paid out £700,000 in legal costs and damages on the condition that Taylor signed a gagging clause to prevent him speaking about the case. The payment is believed to have included more than £400,000 in damages. News Group then persuaded the court to seal the file on Taylor’s case to prevent all public access, even though it contained prima facie evidence of criminal activity.

The Scotland Yard paperwork also provided evidence that the News of the World had been involved with Mulcaire in his hacking of the mobile phones of at least two other people involved in the sporting world. They filed complaints, which were settled this year when News International paid more than £300,000 in damages and costs on condition that they too signed gagging clauses.

Gordon Taylor declined to make any comment. Goodman, now out of jail, said: “My comment is not even ‘no comment’.” A spokesman for News International said: “News International feels it is inappropriate to comment at this time.” A spokeswoman for Cameron said the Tory leader was “very relaxed about the story”.

Former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil described the story last night as “one of the most significant media stories of modern times”. He said: “It suggests that rather than being a one-off journalist or rogue private investigator, it was systemic throughout the News of the World, and to a lesser extent the Sun. Particularly in the News of the World, this was a newsroom out of control.”

Doku-Dreiteiler: „Der Aufstieg der Murdoch-Dynastie“

Der Medienmogul Rupert Murdoch ist einer der mächtigsten Männer der Branche – und einer der gefährlichsten. Unser Mediatheken-Tipp

Vor Jahrzehnten gab es William Randolph Hearst: einen Medienmogul, so mächtig, dass ihn Orson Welles mit „Citizen Kane“ auf die Schippe nahm. Hearst hat seine Macht im Gegenzug benutzt, um den Erfolg des Films zu sabotieren. Was damals Hearst war, ist heute Rupert Murdoch. Dem Unternehmer gehören buchstäblich Hunderte Medienfirmen, darunter der US-Sender Fox News. Sein Einfluss ist immens, ohne ihn hätte es möglicherweise nie einen Präsidenten Trump oder den Brexit gegeben. Der Dreiteiler „Der Aufstieg der Murdoch-Dynastie“ ist nun ein wenig wie Murdochs „Citizen Kane“ – nur mit dem Unterschied, dass alles, was die Filme zeigen, wahr ist.

Der erste Teil mit dem Titel „Der Königsmacher“ beginnt im Jahr 1995. Rupert Murdochs persönliche Beziehung mit Premierminister Tony Blair sorgt im Vereinigten Königreich für Kontroversen. Unter seinem Einfluss lässt sich Blair hinreißen, ein Referendum über den Beitritt zur europäischen Währungsunion abzuhalten. Der Grundstein für den späteren Brexit wird gelegt. Privat muss sich Murdoch entscheiden, welchem seiner Kinder er sein Imperium einst hinterlassen will – Tochter Elisabeth oder doch einem seiner Söhne Lachlan und James? In Rückblenden wird außerdem von seinen verhältnismäßig bescheidenen Anfängen als Zeitungserbe in Melbourne erzählt.

Murdoch: Fall und Wiederaufstieg

Im zweiten Teil „Die Allianz der Rebellen“ baut Murdoch seinen politischen Einfluss auch in den USA aus. Dort verteidigt er den sogenannten Krieg gegen den Terror, die Einsätze in Irak und Afghanistan. Im UK arbeitet er weiterhin auf einen Brexit zu, unterstützt dafür den konservativen Kandidaten David Cameron, den er für leicht manipulierbar hält. Da trifft sein Imperium ein Skandal: Bei der „News of the World“-Affäre kommt heraus, dass seine Zeitungen prominente Mobiltelefone abgehört haben. Sohn James, der diesseits des Atlantiks die Geschäfte leitet, kann nichts dagegen tun, sein Vater verliert Vertrauen zu ihm.

Im dritten Teil „Das Comeback“ kommt unter anderem der populistische Brexit-Befeuerer Nigel Farage zu Wort, der sich einst die Unterstützung von Murdoch sichern konnte. Auf beiden Seiten des Atlantiks sind Murdoch-Medien mitverantwortlich, dass reaktionäre Kräfte an Macht gewinnen: die Europagegner im UK, Donald Trump und seine Präsidentschaft in den USA. Derweilen zerbricht eine Ehe, Murdoch heiratet erneut, seine Kinder sind anwesend, das Imperium heil. Am Schluss der Dokumentation stehen die gigantischen Feuer in Australien – Murdoch und Co. fahren trotzdem fort, den Klimawandel zu leugnen.

„Der Aufstieg der Murdoch-Dynastie“ läuft am 16. Februar in drei Teilen ab 20.15 auf arte. Danach sind die Filme noch bis zum 17. März in der Mediathek verfügbar. 16. Februar 2021 // Matthias Jordan

https://kulturnews.de/doku-dreiteiler-der-aufstieg-der-murdoch-dynastie/

—

Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie

Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie ist eine Programm im deutschen Fernsehen von Arte mit einer durchschnittlichen Bewertung von 4,4 Sternen der Besucher von EtwasVerpasst.de. Wir haben 3 Folgen von Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie in unserem Angebot. Die erste davon wurde im März 2021 ausgestrahlt. Hast du eine Sendung verpasst und willst keine Episode mehr von Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie verpassen? Füge Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie zu Deinen Favoriten hinzu und wir informieren Dich regelmäßig per E-Mail über neue Folgen. Praktisch!

https://www.etwasverpasst.de/der-aufstieg-der-murdoch-dynastie

Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie – Der Königsmacher

Rupert Murdoch ist der mächtigste Mann der Medienwelt. Er besitzt unter anderem den Nachrichtensender “Fox News”, Tageszeitungen sowie Hunderte weiterer Medienunternehmen. Doch wer ist der Mensch hinter dem Medienmogul? Die dreiteilige Doku schildert Murdochs Weg von seinen Anfängen in der australischen Regionalpresse bis an die Spitze eines global agierenden Familienimperiums.

Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie – Die Allianz der Rebellen

Wer ist der Mensch hinter dem Medienmogul Rupert Murdoch? Folge 2/3 befasst sich unter anderem mit dem “News of the World”-Skandal, bei dem über mehrere Jahre Handys von Prominenten und einfachen Bürgern abgehört wurden, um in den Besitz exklusiver Informationen zu gelangen.

Der Aufstieg Der Murdoch-Dynastie – Das Comeback

Die dritte und letzte Folge dokumentiert die anhaltenden Spannungen im Rupert Murdoch-Familienclan. Die dritte Ehe des Unternehmers Murdoch mit der chinesischen Geschäftsfrau Wendi Deng zerbricht an deren vermeintlicher Affäre mit Tony Blair; ab 2013 wird die Brexit-Frage in Großbritannien immer akuter

—

Dennis Christopher George Potter

Dennis Christopher George Potter (Forest of Dean, 17 mei 1935 – Ross-on-Wye, 7 juni 1994) was een Engels toneelschrijver, vooral bekend door The Singing Detective. Zijn televisiedrama’s waren een mengsel van fantasie en werkelijkheid, van persoonlijke en maatschappelijke problemen. Hij maakte met name graag gebruik van thema’s en beelden uit de volkscultuur.

Arthritis psoriatica

In 1962 kreeg Potter symptomen van een acute vorm van psoriasis bekend onder de naam arthritis psoriatica, een zeldzame aandoening die de huid aantastte en artritis in zijn gewrichten veroorzaakte. De rest van zijn leven was Potter herhaaldelijk opgenomen in het ziekenhuis, waarbij hij zich soms op geen enkele manier kon bewegen en vreselijke pijn leed. De ziekte verwoestte uiteindelijk zijn handen, en reduceerde ze tot wat hij “knotsen’ noemde. Hij kon alleen maar schrijven door een pen aan zijn hand vast te binden. Potter bleef, tussen de aanvallen van pijn, misselijkheid en diarree, doorschrijven, waarbij hij een pen in zijn samen geklauwde hand vasthield en schreef dan toch met een opvallend net handschrift. “Ik kan geen typemachine gebruiken”, zei hij, “omdat mijn strompelende vingers dan meer dan een toets tegelijk aan zouden slaan.” Het script van de “Son of Man”, dat voornamelijk in het ziekenhuis was geschreven, werd afgeleverd met spetters bloed en vegen corticosteroïdenzalf.

Weduwnaar en dood

Een paar maanden voordat bij Potter de diagnose alvleesklierkanker werd gesteld, hoorde zijn vrouw Margaret Morgan Potter dat ze borstkanker had. Ondanks zijn eigen verslechterende toestand en slopende werkschema, bleef Potter voor haar zorgen tot zij op 29 mei 1994 stierf. Hij overleed negen dagen later in Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, Engeland, 59 jaar oud.

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dennis_Potter

Dennis Christopher George Potter (17 May 1935 – 7 June 1994) was an English television dramatist, screenwriter and journalist. He is best known for his BBC television serials Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), and the BBC television plays Blue Remembered Hills (1979) and Brimstone and Treacle (1976).[1] His television dramas mixed fantasy and reality, the personal and the social, and often used themes and images from popular culture. Potter is widely regarded as one of the most influential and innovative dramatists to have worked in British television.

Born in Gloucestershire and graduating from Oxford University, Potter initially worked in journalism. After standing for parliament as a Labour candidate at the 1964 general election, his health was affected by the onset of psoriatic arthropathy which necessitated Potter changing careers and led to him becoming a television dramatist. His new career began with contributions to BBC1‘s regular series The Wednesday Play from 1965, and he continued to work in the medium for the rest of his life, including writing screenplay adaptations for Hollywood studios. Potter died of pancreatic cancer in 1994.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dennis_Potter

A Parting Shot from Dennis Potter

Dennis Potter – Seeing the Blossom

‘We tend to forget that life can only be defined in the present tense’

Edited version of Melvyn Bragg’s interview of Dennis Potter on March 15 1994. It was broadcast by Channel 4 on April 5 1994 Video: Melvyn Bragg remembers the Potter interviewWed 12 Sep 2007 15.33 BST

Melvyn Bragg: How did you, and when did you, find out that you’d got this cancer?

Dennis Potter: Well, I knew for sure on St Valentine’s day, [laughs] like a little gift, a little kiss from somebody or something. Obviously I had suspicions. I had a lot of pain before then and there was a quite accidental sort of misdiagnosis of the condition. In a way it was almost a relief to find out what it was: cancer of the pancreas with secondary cancers already in the liver and the knowledge that it can’t be treated. There’s no … neither chemotherapy nor surgery are appropriate, it’s just simply analgesic care until, you know: Goodnight Vienna, as they say in football nowadays. [laughs] And I’ve been working since then, flat out at strange hours, ’cause I’m done in the evenings, because of the morphine. The pain is very energysapping, but I do find that I can, I can be at my desk at five o’clock in the morning, and I’m keeping to a schedule of pages, and I will and do meet that schedule every day.

I grieve for my family and friends who know me closest, obviously, and they’re going through it in a sense more than I am. But I discover also what you always know to be true, but you never know it till you know it, if you follow (sorry, I’ve got … my voice is echoing in my head for some reason).

We all, we’re the one animal that knows that we’re going to die, and yet we carry on paying our mortgages, doing our jobs, moving about, behaving as though there’s eternity in a sense. And we forget or tend to forget that life can only be defined in the present tense; it is is, and it is now only. I mean, as much as we would like to call back yesterday and indeed yearn to, and ache to sometimes, we can’t. It’s in us, but we can’t actually; it’s not there in front of us. However predictable tomorrow is, and unfortunately for most people, most of the time, it’s too predictable, they’re locked into whatever situation they’re locked into … Even so, no matter how predictable it is, there’s the element of the unpredictable, of the you don’t know. The only thing you know for sure is the present tense, and that nowness becomes so vivid that, almost in a perverse sort of way, I’m almost serene. You know, I can celebrate life.

Below my window in Ross, when I’m working in Ross, for example, there at this season, the blossom is out in full now, there in the west early. It’s a plum tree, it looks like apple blossom but it’s white, and looking at it, instead of saying “Oh that’s nice blossom” … last week looking at it through the window when I’m writing, I see it is the whitest, frothiest, blossomest blossom that there ever could be, and I can see it. Things are both more trivial than they ever were, and more important than they ever were, and the difference between the trivial and the important doesn’t seem to matter. But the nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous, and if people could see that, you know. There’s no way of telling you; you have to experience it, but the glory of it, if you like, the comfort of it, the reassurance … not that I’m interested in reassuring people – bugger that. The fact is, if you see the present tense, boy do you see it! And boy can you celebrate it.

Do you spend much time thinking about your childhood and raking through that, Dennis, and the time in the Forest of Dean, the time with your parents? Because you’ve written about it often. Where is it now, as it were, in your …

Where is the Forest of Dean? It’s still back there. It’s a sort of mythic Forest of Dean. There’s the real one (laughs), with the same signs and stresses as the real anywhere, and there’s the other one, the one I grew up as a small child in, and those rather ugly villages in beautiful landscape. Just accidentally a heart-shaped place between two rivers, somehow slightly cut off from them, the rest of England and Wales on the far side, the other border …

Do you look back and … I mean, a lot of people think that you see your childhood in … there are terrors in it, but it is some kind of place in England that was a particular period in the lives of a lot of people which was to do with a sense of community. Now, we’ve both been through that, and we know that things were wrong – awful and terrible and so on – but there’s a glow there. Is it a glow because you’re a middle-aged man looking back? Well, it’s partly that and it’s partly … it’s true the fact about childhood, which I tried to do in things like Blue Remembered Hills, for example. I used adult actors to play children in order to make them like a magnifying glass, to show what it’s like. And because if you look at a child, talk about present tense, that’s all they, all a small child lives in. So a wet Tuesday afternoon can actually be years long, and it – childhood – is full to the brim of fear, horror, excitement, joy, boredom, love, anxiety … Maybe you kind of revert to that in a way, but my Forest of Dean childhood, well … it is a strange and beautiful place, with a people who were as warm as anywhere else, but they seemed warmer to me, and the accent is almost so strong, it’s almost like a dialect.

Up the hill three times, well, twice actually, usually on a Sunday, sometimes three times to Salem Chapel and those little floppy, orange-covered hymn books, Ira Sankey’s 1,200 Sacred Songs and Solos and all this. Numbers would be slotted up on the board like those choruses, like … There’s one I’m trying to – it’s funny, I can think of the number before I can think of the chorus, I can see it as clear as though it were written in front of me on the slat – 787, hymn number 787: “Will there be any stars, any stars in my crown, when the evening sun goes down, when I wake with the blessed in the mansion of rest, will there be any stars in my crown?” And, of course, it makes me laugh, and yet it tugs at me. And for me, of course it was the Holy Land – I knew Cannop Ponds by the pit where Dad worked, I knew that was where Jesus walked on the water; I knew where the Valley of the Shadow of Death was, that lane where the overhanging trees were.

We were poor, yes. Dad was a coalminer, reserved occupation, so he didn’t go in the army. But the whole country at that time was politicised; even children knew what the war was about. I mean, we did. We English tend to deride ourselves far too easily, because we’ve lost so much confidence, because we lost so much of our own sense of identity, which had been subsumed in this forced imperial identity which I obviously hate. But we were, at that time, both a brave and a steadfast people, and we shared an aim, a condition, a political aspiration if you like, which was shown immediately in the 1945 general election, and then one of the great governments of British history – those five, six years of creating what is now being so brutally and wantonly and callously dismantled was actually a period to be proud of, and I’m proud of it.

You don’t mind this cigarette? I mean, I always have smoked, but…

Why should I mind?

Well, people do nowadays. You get so bloody nervous smoking.

It’s all right, I’m a very passive smoker.

Thank God I don’t have to go to America any more. It’s easier to pull a gun in America than a cigarette out of your pocket. Now I’m just virtually chain-smoking, because there’s no point in … There’s so many things, like I can’t keep food down any more. I can’t have a meal, my digestive system’s gone, but I can drink things, and those prepared, those horrible chemical things with all the minerals and stuff in them, but I can add a dash of this and that to it, which I do, and … like cholesterol, aawww! I can break any rule now, you know, I can do it. But the cigarette, well, I love stroking this lovely tube of delight. Look at it (laughter).

I’ve packed in. Now stop, or I’ll be smoking again in a minute, Dennis, with you. It’s been written about so much and derided so much, people from working-class backgrounds getting to Oxford … Do you think the driving themes in your work have come from your childhood or did they come from what happened after the break to university and the first few years’ university journalism?

Dunno, Melvyn. They come as you grow, and your childhood remains. I mean, I forget, I’ve forgotten who said it, but I remember reading some essay by some writer saying that for any writer, the first 14 years of his or her life are the crucible anyway, no matter what you do. But of course you add on and you use your experiences and I, I’ve always deliberately, as a device, used the equivalent of a novelist’s first-person narrative. You know when the novelist says I, he doesn’t mean I, and yet you want him to mean I, and I’ve used, for example in The Singing Detective, I used the Forest of Dean, I used the physical circumstances of psoriatic arthropathy, which, you know, I’ve still got bloody psoriasis itching away at me, which is a bugger. You’d think that would lay off now, wouldn’t you, but it won’t! But I used that, and geographical realities, and it seemed so personal then, but I often do that. It isn’t. I make it up, the story. You know the wife thing? The whole inner structure of that man is different to me. Now he was a man, the Singing Detective, Michael Gambon character, the Philip Marlow in a hospital bed at the beginning who had nothing. He was stripped of everything. He had no faith in himself, no belief in any political, religious or social system. He was full of a witty despair and cynicism. Now I have never been like that, and the dramatic story was very simple. It was simply seeing a man pick up his bed and walk. It’s interesting, I always fall back into biblical language, but that again, you see, is part of my heritage, which I, in a sense, am grateful for.

Do you feel you were thought of at one stage as a political writer, at a very early stage? Your first appearance on television was talking about class to some in some documentary programme.

Yes, that’s right.

And then Stand Up, Nigel Barton, you stood as a Labour candidate, you worked with the Daily Herald and so on. Where does that figure now, Dennis, and when did it figure? Was it a …

I realised that somewhere along the line my pen was actually going to provide me with a living. Politics seemed the gateway. My very first book I wrote as an undergraduate, although a printing strike delayed it until a year after I left Oxford – it came out in 1960.

The Glittering Coffin?

… called The Glittering Coffin, yes, which was a kind of metaphor for the condition of England. Typical young man’s title, you see, typical piece of that sort of humbugging, canting rhetoric, which young men – bless their hearts – specialise in. We should always look back on our own past with a sort of tender contempt. As long as the tenderness is there, but please let some of the contempt be there, because we know what we are like, we know how we hustle and bustle and shove and push and sometimes use grand words to cloak it; one does. I’m not looking at you specifically, so don’t squirm [laughter].

Just associating bodily there.

Politics was – seemed – the door, until I actually stood as a candidate. By then, of course, illness had descended and I had a walking stick and I was drowning actually, drowning, felt that I was … On the Daily Herald I hated every second of it. And that world of popular journalism, as I saw it then, and the Herald eventually mutated through the mismanagement of the Mirror Group, its eventual owners, into … There’s an interesting thing: one of the favourite fantasy plots of a writer is a character is told “You’ve got three months to live” and – which is what I was told – and you, who would you kill? (laughs). I call my cancer, the main one, the pancreas one, I call it Rupert, so I can get close to it, because the man Murdoch is the one who, if I had the time – in fact I’ve got too much writing to do and I haven’t got the energy – but I would shoot the bugger if I could. There is no one person more responsible for the pollution of what was already a fairly polluted press, and the pollution of the British press is an important part of the pollution of British political life.

In your own writing, there was a time when it seemed to me, and to a lot of people, that there were novels being written and plays being put on on stage and films being made, but the power of very good writers, directors, cameramen talking to a large public was on television and you were pushing it again and again. You were bringing up ideas of the devil, you were bringing up ideas of dialogue turning into singing. You were bringing up ideas of memory matching with fantasy and so on. Did you … you obviously found television available to everything you wanted to do, and you made it available for a lot of other people.

It could be, and can be, and I reached a stage and I’ve written so many things down over so many years of working for television – obviously, I’m 58. I might reach my … 59 on May 17. I might get there. It’d look neater, wouldn’t it, to die 59? But technique, I don’t think about any more. It’s just natural to me, I don’t even … it’s like with a musician …

What about subject matter? Was there anything … did you feel that you were being daring doing any of the things you did in it? Did you think, I am going to be …

That’s the only thing I really resent, that’s the only thing I would stamp my foot about. I never have … This is, I was going to say the gospel truth, here I go again, but this is the truth, Melvyn, that I have never felt the need to do that. It has come, the mould, if broken on any one point, has come out of the need to do what I was doing. Not, “How do I break the mould?” It’s the other way round, so things have happened. The way they come, I remember, it’s … it always sounds so mundane but, for example, the use of adults to play children in Blue Remembered Hills was, is just … I was starting to write about children and I wanted to write something difficult because children don’t have long speeches; you can’t have flashbacks to nonexistent memories. You can’t have certain rhetorical devices. You have to have a continual twitchy action because that’s how children move. And these were a group of seven seven-year-olds, and the only, ultimately the only, way I could see, while keeping exactly to the language of childhood and the movements of childhood and the constant present-tense preoccupations of childhood, to show it without that filter coming in the way, which an audience going “Ah, children” and immediately pushing it back to childhood, was by using adults, seven adult actors. Once you get over the panic of the first five minutes, when I think, my God, is this … ? Colin Welland’s great fat arse and great shorts addling, sploshing through mud, making aeroplane noises, and chewing on an apple, and I thought, oh, you know, it’s going to be one of those dire, dread embarrassments, because it ain’t gonna work. And yet after a while people could see obviously that these were adults. But they also saw that they were children, so it worked. It wasn’t because I was trying – do you see what I’m getting at? I was trying to show childhood not at one remove but straight on.

What about bringing in popular songs, as you did, say, with Pennies from Heaven?

That, I wanted to write about – in a sense it sounds condescending, and I don’t mean it quite this way – I wanted to write about the way popular culture is an inheritor of something else. You know that cheap songs so-called actually do have something of the Psalms of David about them. They do say the world is other than it is. They do illuminate. This is why people say, “Listen, they’re playing our song”, or whatever. It’s not because that particular song actually expressed the depth of the feelings that they felt when they met each other and heard it. It is that somehow it re-evokes and pours out of them yet again, but with a different coating of irony and selfknowledge. Those feelings come bubbling back. So I wanted to write about popular songs in a direct way. It became just a technical problem for me. Not interested in writing a musical. A musical has a different grammar: the action builds to a song and then a song caps it and then it moves on. Then I thought, well, they lip-synch things now and again. You know, like sometimes there’s a bad performance or they dub from one language to another. Why don’t I just try making the actor move his lips to the words of the song? Then I tried it a bit, I tried it with myself in a mirror, and that was fun. I mean, I was pre-karaoke and I wasn’t breaking a mould as such. I just found the ideal way of making these songs so real.

[I] dislike, and I can understand it, the use of this word controversial, but there were many times when you really seemed to bump into opinion in this country. Can we talk about Brimstone and Treacle, the vision of a devil …

Ah, Brimstone and Treacle was … Can I break off for a second? I need a swig of that – there’s liquid morphine in that thing. I’ll keep going but I … Can you unscrew that cap? I … this is not agitation about Brimstone and Treacle by the way.

Are you feeling OK? How much … how much time?

It’s better to go on.

Why do you think you got so much resistance in Brimstone and Treacle?

It’s a very complicated story, but if I could put in essence what I saw I was trying to do: it’s … in a way it’s a simple flip-over of an ordinary sentimental religiose, rather than religious, parable, in that there is an afflicted house – variously afflicted, but in particular with a crippled, seemingly mindless, struck girl, young girl. And there is a visitor, and the visitor brings her to life and makes her speak. Now, if that visitor were an angel, then all you would have is sanctimoniousness, you would learn nothing about anything. What if it were the devil? Instead of making that easy distinction which, on the whole, only the blasphemous make – non-religious people make this distinction very easily, between so-called good and so-called evil, when of course they are interrelated, and one is defined in terms of the other. So instead of the angel coming and rescuing the cripple and the dumb and the afflicted, I had the devil do it. The evil act can lead to good consequences; a good act can lead to evil consequences. This is often the case, and it is … it is incomprehensible. It is as though, you know, the rain falls on the just and upon the unjust. It is so. Now, it appeared disgusting because it was a devil, and because it was a rape, or the beginnings of a rape, that made her cry out; and interestingly, the cry out was actually an accusation against her father. That complexity is, as I say, simply a reversal of what would have been sanctimonious and sentimental.

Thanks a lot.

That’ll have to do. I’m done. I need that thing again, I’m sorry. I felt OK, you see. At certain points, I felt I was flying with it.

You were.

And so … I’m grateful for the chance. This is my chance to say my last words. So, thanks.

· Interview reproduced by permission of ITN Source/Channel 4. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2007/sep/12/greatinterviews