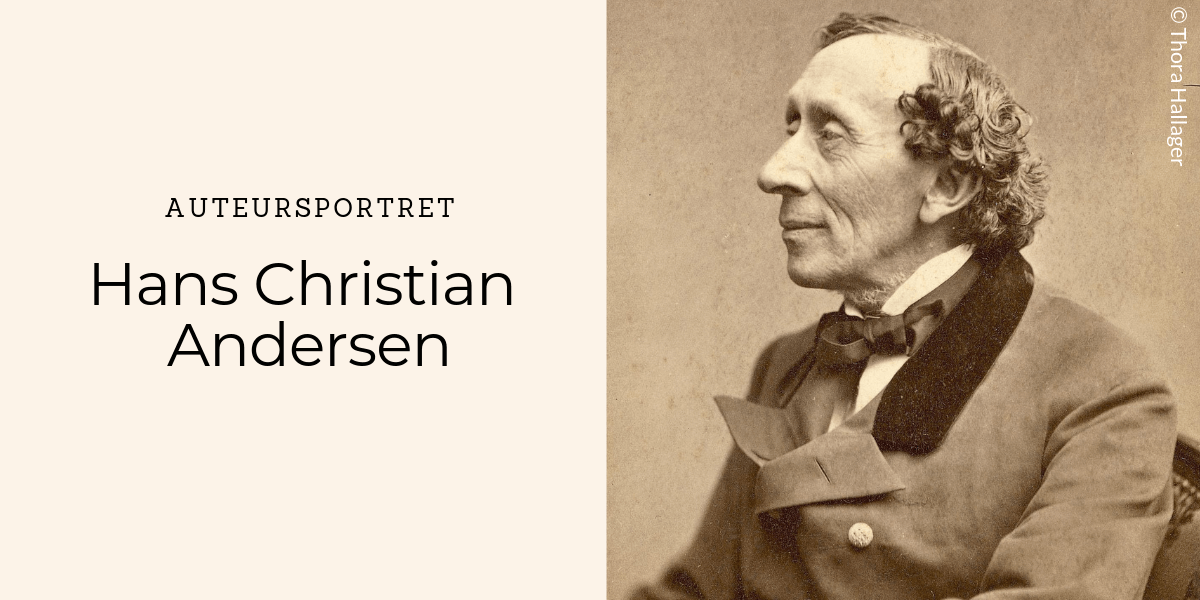

Hans Christian Andersen in 1874

Hans Christian Andersen (Odense, 2 april1805 – Kopenhagen, 4 augustus1875) was een Deensschrijver en dichter, het bekendst om zijn sprookjes. In eigen land wordt hij gewoonlijk bij zijn voorletters H.C. Andersen genoemd .(Deense uitspraak: Ho Cee Annersen)

Biografie

Hans Christian Andersen werd geboren en groeide op in Odense, in grootte de derde stad van Denemarken. Zijn vader was schoenmaker en overleed toen Hans Christian 11 jaar oud was. In zijn vroege jeugd speelde hij graag met zijn poppenkast. Hij wilde graag acteur worden, maar werd niet aangenomen bij de koninklijke theaterschool (1819). Zijn opleiding kreeg hij aan een school voor armen, totdat hij op 17-jarige leeftijd via vrienden een beurs kreeg voor een goede school. Op deze laatste school werd hij veel gepest door leraren en leerlingen. Andersen stond bekend als een verlegen en stil persoon, niet goed in de omgang met anderen. Daarom wordt gezegd dat Het lelijke eendje een autobiografisch sprookje is; hierin wordt een lelijk eendje een mooie zwaan, zo ook in het echte leven van Andersen: de ‘zwakkeling’ wordt een beroemd schrijver.

Zijn debuut was in 1827 met het gedicht Det døende Barn (Het stervende kind) dat hem zeer onder de aandacht bracht. In 1835 werd de roman Improvisatoren (De improvisator) uitgebracht na een studiereis door Europa. Deze roman was zowel een pittoreske beschrijving van Italië als een autobiografie. In 1835 werd ook zijn eerste verzameling Eventyr, fortalt for Børn (Sprookjes, aan kinderen verteld) uitgegeven. Dit waren hervertellingen van veelal traditionele sprookjes. Het was geschreven in een verfijnde vorm, vaak met een dubbele bodem, die voor kinderen te begrijpen was, terwijl de bundel op volwassenen geënt was. Zijn latere sprookjesbundels, vol eigen sprookjes met een grote spanwijdte, weken verder en verder van kinderliteratuur af. Ze vallen in meerdere categorieën uiteen, vanaf de poëtisch-filosofische mythe tot aan realistischer korte verhalen. Gemeenschappelijk is echter het humoristische inzicht van Andersen.

Andersen schreef meerdere autobiografieën, maar het in 1855 gepubliceerde Mit Livs Eventyr (het sprookje van mijn leven) geldt als de belangrijkste.

Ook was hij een graag geziene maar bovenal gehoorde gast aan het hof van koningin Victoria.

Andersen hield een uitgebreid dagboek bij. Uit dit dagboek weten we dat Andersen drie bezoeken heeft gebracht aan Amsterdam in 1847, 1866 en 1868. Hij logeerde aldaar bij koopman Brandt die woonde in de grootste van de vier Cromhouthuizen aan de Herengracht 368. Andersen zou er ook aan een sprookje hebben gewerkt, maar het is niet bekend welk. In 1866 bracht Andersen ook een bezoek aan Den Haag, Leiden en Katwijk, waar hij samen met schrijver Johannes Kneppelhout (‘Klikspaan’) de sluizen bezocht waardoor de Oude Rijn in zee stroomt.

Dood

In het voorjaar van 1872 viel Andersen uit zijn bed en raakte hij ernstig gewond. Hij herstelde niet meer volledig maar leefde nog tot 4 augustus 1875. Zijn lichaam werd bijgezet op Assistens Kirkegård in Kopenhagen. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Christian_Andersen

—-

Jugend und Ausbildung

Das wahrscheinliche Geburtshaus Andersens in OdenseAndersens Kindheitsheim in Odense

Hans Christian Andersen wurde als Sohn des verarmten Schuhmachers Hans Andersen (1782–1816) und der alkoholkranken Wäscherin Anne Marie Andersdatter (ca. 1775–1833) in Odense auf Fünen geboren.

Nach dem Tod seines Vaters ging er mit 14 Jahren nach Kopenhagen und bemühte sich, dort als Schauspieler zum Theater zu kommen. Als ihm das jedoch nicht gelang, versuchte er sich ebenso vergeblich als Sänger und verfasste schon erste kleine Gedichte. Schließlich nahm ihn Konferenzrat Jonas Collin, der damalige Direktor des Kopenhagener Königlichen Theaters, in seine Obhut und in sein Haus auf. Dort fühlte er sich besonders zu dem Sohn seiner Gasteltern, Edvard Collin, hingezogen, den diese Zuneigung jedoch eher befremdete und der diese nicht erwiderte. Eine enge Freundschaft verband ihn mit der jüngsten Tochter Louise Collin.

Von der Theaterdirektion unterstützt und durch König Friedrich VI. gefördert, konnte er von 1822 bis 1826 bei Rektor Simon Meisling eine Lateinschule in der kleinen Provinzstadt Slagelse besuchen, von 1826 bis 1828 eine weitere Lateinschule in Helsingør und anschließend die Universität Kopenhagen.

Erste Werke und Reisen

Am Ende seiner Schulzeit entstand das Gedicht Das sterbende Kind, in dem der Autor die Welt aus der Sicht eines kleinen Kindes beschrieb. Diese Perspektivwahl wurde später typisch für sein literarisches Schaffen. Das Gedicht wurde in mehreren Sprachen veröffentlicht. In dieser Zeit schrieb Andersen im Alter von ca. 18 Jahren auch sein erstes, unveröffentlichtes Märchen vom Talglicht, dessen Manuskript erst 2012 gefunden wurde.[2]

Andersen verliebte sich in Riborg Voigt, die Schwester seines Studienfreundes Christian Voigt. Allerdings war sie bereits einem anderen Mann versprochen. Ihren Abschiedsbrief bewahrte er zeitlebens in einem Ledersäckchen auf, das man erst nach seinem Tod fand.

Nach der Heirat Riborgs unternahm Andersen mehrere Reisen nach Deutschland, England, Italien, Spanien, Portugal und in das Osmanische Reich. Unter dem Einfluss der italienischen Landschaft entstanden die ersten Vorformen der Kleinen Meerjungfrau. Die Beschreibung der Welt in dem gleichnamigen Märchen zeigt deutlich italienische Einflüsse. Auf seinen insgesamt 30 großen Reisen kam er 32-mal nach Dresden und 15-mal nach Maxen bei Dresden, wo er seine Freunde besuchte, die Mäzene Friederike und Friedrich Anton Serre. Dort schrieb er auch: „Des Herzens Sonnenschein in Sachsen, er strahlt am schönsten doch in Maxen.“

Spätere Jahre

In seinen späten Jahren war er mit vielen bekannten Frauen befreundet: Henriette Wulff († 13. September 1858 beim Brand der Austria), Tochter des Kommandeurs P. F. Wulff, ferner Sophie Ørsted, Tochter des Entdeckers des Elektromagnetismus Hans Christian Ørsted, und Jenny Lind, auch „die schwedische Nachtigall“ genannt, die er sehr verehrte. Andersen blieb jedoch lebenslang unverheiratet. Mit Edvard Collin verband ihn jedoch auch nach dessen Heirat im gegenseitigen Einvernehmen eine Freundschaft auf Distanz. Im Hans-Christian-Andersen-Center befindet sich sein umfangreicher Briefwechsel, darunter der Brief der Malerin Clara Heinke (älteste Tochter des Juristen Ferdinand Heinke), in dem sie ihm im August 1872 den Tod Friederike Serres mitteilt.

In der Wissenschaft wird kontrovers diskutiert, ob Andersen homosexuell gewesen sei. Diese Diskussion begann schon im 19. Jahrhundert und wurde 1901 mit dem Artikel Hans Christian Andersen: Beweis seiner Homosexualität von Carl Albert Hansen Fahlberg (Albert Hansen) in Magnus Hirschfelds Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen erstmals vertieft. Jüngere Untersuchungen haben versucht, in Andersens Märchen und Romanen insbesondere das Thema der homoerotischen Maskierung herauszuarbeiten.

Andersen war Hypochonder und wurde von einer Vielzahl von Ängsten geplagt. Seine Weltanschauung war der Pantheismus, Gott wird „naturalisiert“.

Im Mai 1874 empfing der Dichter den Fotografen Clemens Weller der Firma Hansen, Schou & Weller, um Aufnahmen von sich in seinen Privaträumen anfertigen zu lassen. Im September des Jahres fertigte Georg Emil Hansen die letzten Aufnahmen. Andersen starb siebzigjährig als international anerkannter und verehrter Dichter am 4. August 1875 in Kopenhagen und wurde dort auf dem Kopenhagener Assistenzfriedhof beigesetzt.Denkmal für Hans Christian Andersen von August Saabye, Kopenhagen, Kongens Have, 1880

Noch zu Lebzeiten sollte für Hans Christian Andersen im Kongens Have in Kopenhagen ein Denkmal errichtet werden. Anlässlich seines 70. Geburtstags am 2. April 1875 bekam er die Zusage, dass genug Geld für ein Monument eingesammelt worden war, das allerdings erst fünf Jahre nach seinem Tod am 26. Juni 1880 feierlich enthüllt werden konnte. Das bemerkenswerte ist, dass Andersen persönlich Einfluss auf die Gestaltung seines Denkmals genommen hat; denn er ärgerte sich darüber, dass er auf vielen Skizzen, die zu dem ausgeschriebenen Wettbewerb eingesendet wurden, von Kindern umringt dargestellt wurde. Er wollte nie auf seine Rolle als Märchenerzähler für Kinder reduziert werden, weil seine Geschichten oft satirische Merkmale haben, die nur von Erwachsenen in ihrer ganzen Bedeutung als Gesellschaftskritik erfasst werden können. Der dänische Bildhauer August Saabye hat Hans Christian Andersen sitzend dargestellt, wie er zu seinem Publikum spricht. In seiner linken Hand hält er das Buch, aus dem er vorgelesen hat und steckt die Finger als kurzzeitiges Lesezeichen zwischen die Buchseiten, während er die Geschichte mündlich weitererzählt. Die Seiten des Sockels sind mit zwei Reliefs aus seinen Geschichten verziert: Das hässliche Entlein und Die Geschichte des Jahres.

Werke

Hans Christian Andersen, der seinen Namen als Verfasser stets H. C. Andersen abzukürzen pflegte, wurde durch seine zahlreichen Märchen (dänisch: Eventyr) berühmt – 156 insgesamt. Die folgende Aufzählung orientiert sich an der Reihenfolge in den zwei Bänden Gesammelte Märchen. Arthur Szyk: Frontispiz zu einer amerikanischen Ausgabe von Andersens Märchen. New York 1945. Zu erkennen sind unter anderem Die Schneekönigin, Der standhafte Zinnsoldat und Des Kaisers Nachtigall.

- Das Feuerzeug

- Der kleine Klaus und der große Klaus

- Die Prinzessin auf der Erbse

- Die Blumen der kleinen Ida

- Däumelinchen

- Der Reisekamerad

- Die kleine Meerjungfrau

- Des Kaisers neue Kleider

- Die Galoschen des Glücks

- Das Gänseblümchen

- Der standhafte Zinnsoldat

- Die wilden Schwäne

- Der Garten des Paradieses

- Der fliegende Koffer

- Die Störche

- Ole Lukøje

- Der Schweinehirt

- Der Buchweizen

- Der Engel

- Des Kaisers Nachtigall

- Die Brautleute

- Das hässliche Entlein

- Der Tannenbaum

- Die Schneekönigin

- Mutter Holunder

- Die Stopfnadel

- Die alte Kirchenglocke

- Erlenhügel

- Die roten Schuhe

- Der Springer

- Die Hirtin und der Schornsteinfeger

- Holger Danske

- Das kleine Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern

- Die Nachbarsfamilien

- Der kleine Tuk

- Der Schatten

- Das alte Haus

- Der Wassertropfen

- Die glückliche Familie

- Die Geschichte von einer Mutter

- Der Kragen

- Unterschiede müssen sein

- Die schönste Rose der Welt

- Die Geschichte des Jahres

- Es ist ganz gewiss

- Das Schwanennest

- Herzeleid

- Alles an seinen rechten Platz

- Das Heinzelmännchen beim Speckhöker

- Unter dem Weidenbaum

- Fünf aus einer Erbsenschote

- Sie taugte nichts

- Zwei Jungfern

- Am äußersten Meer

- Das Geldschwein

- Ib und die kleine Christine

- Tölpel-Hans

- Der Flaschenhals

- Suppe von einem Wurstspeiler

- Etwas

- Der letzte Traum der alten Eiche

- Die Tochter des Schlammkönigs

- Die Schnellläufer

- Die Glockentiefe

- Der Wind erzählt von Waldemar Daae und seinen Töchtern

- Kindergeschwätz

- Ein Stück Perlenschnur

- Das Kind im Grabe

- Der Hofhahn und der Wetterhahn

- Eine Geschichte aus den Dünen

- Der Mistkäfer

- Was Vater tut, ist immer recht

- Der Schneemann

- Die Eisjungfrau

- Der Schmetterling

- Der Bischof auf Börglum und seine Sippe

- In der Kinderstube

- Die Teekanne

- Das Heinzelmännchen und die Madam

- Verwahrt ist nicht vergessen

- Der Sohn des Pförtners

- Des Paten Bilderbuch

- Die Lumpen

- Was die Distel erlebte

- Die Wochentage

- Der Gärtner und die Herrschaft

- Der Krüppel

- Griechenland und der Orient – eine märchenhafte Reise

Andersen bearbeitete Volksmärchen, bis sie seinen literarischen Ansprüchen genügten. Angelehnt an dänische, deutsche, griechische und mittelalterliche Sagen und historische Begebenheiten, dem Volksglauben verbunden und inspiriert von literarischen Strömungen seiner Zeit, aber auch von Naturphänomenen, schuf Andersen so die bedeutsamsten Kunstmärchen des Biedermeier. Andersens Märchen, die teilweise anderen bedeutenden dänischen Künstlern, wie dem Dichter Ambrosius Stub oder dem Bildhauer Bertel Thorvaldsen die Reverenz erweisen, sind nicht nur zeitlos; sie gehören längst zur Weltliteratur.

Allerdings sind etliche dieser 156 Märchen, so wie auch die autobiografischen Texte, Novellen, Dramen, Gedichte und Reiseberichte, die von seinem Schaffensreichtum zeugen, eher unbekannt. Auch als Romancier ist Andersen kaum bekannt: 1835 erschien als sein erster Roman Der Improvisator, den er während eines Italien-Stipendiums schrieb, und neben weiteren Romanen 1848 Die beiden Baroninnen, eine Waisenkind-Geschichte. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Christian_Andersen

—–

Er was eens een schoenmakerszoon.

Hij ging maar veertien dagen blijven. Uiteindelijk verbleef hij vijf weken bij de familie Dickens. Voor Charles Dickens (1812-1870) was Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) een slechte huisgast. Niet lang daarna verbrak hij zijn vriendschap met de rare en saaie Deen. De twee literaire reuzen hadden elkaar, tien jaar eerder, in 1847, leren kennen tijdens een promotour van Andersen in Engeland. Het klikte meteen. Dickens had bewondering voor het werk van Andersen, en Andersen was een fan van Dickens. Bovendien schreven beide over het moeilijke leven van de armen. Een leven waar ze beide vertrouwd mee waren.

Een buitenstaander

Heel zijn leven woonde H.C. Andersen als gast bij aristocratische en gegoede families in binnen- en buitenland. Hij was weliswaar een graag geziene gast, maar echt aanvaard werd hij niet. Zo was er Andersens persoonlijkheid. Hij was een stille man, onhandig in sociale situaties. Ook zijn lage afkomst speelde hem parten. Tijdgenoten waren sceptisch over zijn talent. Hij was namelijk uit de verkeerde broek geschud: zijn vader was een schoenmaker en zijn moeder een wasvrouw.

Toen zijn vader stierf, was Andersen nog maar elf en combineerde hij sporadische lessen op school met een opleiding als leerjongen. Andersen ging vervolgens in de leer bij een wever, tabakshandelaar en kleermaker, maar hij wist dat dit niet zijn toekomst was. Hij verzon liever verhalen en imiteerde acrobaten en toneelspelers. Op zijn veertiende besliste hij om zijn geluk in Kopenhagen te beproeven.

Het verschil tussen zijn geboortestad Odense en Kopenhagen was groot. In Odense was Andersen opgegroeid met oude tradities, bijgeloven en een schat aan volksverhalen. Kopenhagen, daarentegen was een stad van boeken en beschaving. Hier zocht Andersen zijn fortuin in het theater. Een carrière als zanger, balletdanser of acteur zat er niet in. Dus probeerde hij het als toneelschrijver. In 1822 werd hij ontdekt door de toenmalige directeur van Det Kongelige Teater (Royal Theatre), Jonas Collin. Collin zag literair talent in de vreemde jonge man en werd zijn beschermheer. Dankzij het geld, dat Collin bijeen kreeg, ging Andersen terug naar school. Graag ging Andersen niet naar school. Het schoolhoofd hield hem immers altijd voor dat hij geen schrijver kon worden.

Schrijven in spreektaal

Andersen was een productieve schrijver. Naast toneelstukken schreef hij gedichten, romans, libretto’s, reisverslagen, autobiografieën en sprookjes. Met de sprookjes kwam de nationale en internationale roem. Ze waren revolutionair. Aanvankelijk schreef hij de volksverhalen op, die hij in zijn jeugd had horen vertellen, maar hij begon al snel zijn eigen sprookjes te schrijven. Ondanks zijn scholing leerde Andersen nooit goed schrijven en spellen. Hij schreef in spreektaal, waardoor hij brak met een literaire traditie. Zijn talent om verhalen te vertellen met veel fantasie en elementen uit de volkse traditie was een recept voor succes.

Zijn beste sprookjes schreef hij voor volwassenen, maar ze waren evengoed geliefd bij kinderen. Niet alleen in eigen land, maar ook in het buitenland entertainde Andersen mensen met zijn sprookjes. Koningen, edelen en rijken stelden hun paleizen en huizen open voor Andersen, die hen en hun gasten voorlas uit eigen werk. In totaal schreef Andersen 169 sprookjes. Met ‘Het lelijke jonge eendje’ schreef hij, naar eigen zeggen, het verhaal van zijn leven. Net als het lelijke eendje was hij een buitenstaander, een status waar hij zwaar onder leed. Een schoenmakerszoon, die ondanks alles, was uitgegroeid tot een beroemd schrijver. https://daniellecobbaertbe.com/2019/04/02/hans-christian-andersen/

—–

Bibliografie

Sprookjes

Sprookjesboek uit 1910Engelse vertaling van de sprookjes van Hans Christian Andersen, 1914Een bordje bij De rode schoentjes in het Sprookjesbos in de Efteling ter gelegenheid van het Hans Christian Andersen jaar 2005![]() Zie Lijst van sprookjes en overige vertellingen van Hans Christian Andersen voor het hoofdartikel over dit onderwerp.

Zie Lijst van sprookjes en overige vertellingen van Hans Christian Andersen voor het hoofdartikel over dit onderwerp.

Enkele bekende sprookjes zijn:

- De prinses op de erwt

- De nieuwe kleren van de keizer

- De Chinese nachtegaal

- Het lelijke eendje

- De kleine zeemeermin

- De rode schoentjes

- Het meisje met de zwavelstokjes

- De standvastige tinnen soldaat

- De sneeuwkoningin

- Duimelijntje

- De wilde zwanen

- De tondeldoos

- Klaas Vaak

- De mestkever

Romans

- Improvisatoren (De improvisator) (1835)

- O.T. (1836)

- Kun en Spillemand (Alleen een violist) (1837)

- De to Baronesser (De twee baronessen) (1848)

- At være eller ikke være (Zijn of niet zijn) (1857)

- Lykke-Peer (Blije Peer) (1870)

Drama’s

- Bruden fra Lammermoor (De bruid uit Lammermoor) (1832)

- Ravnen eller Broderprøven (De raaf of de broederschapstest) (1832)

- Agnete og Havmanden (Agnete en de zeeman) (1833)

- Festen paa Kenilworth (Het feest bij Kenilworth) (1836)

- Den Usynlige paa Sprogø (Het onzichtbare op Taaleiland) (1839)

- Mulatten (1840)

- Maurerpigen (Metselwerk) (1840)

- Kongen drømmer (De koning droomt) (1844)

- Lykkens Blomst (Bloem van geluk) (1845)

- Den nye Barselstue (De nieuwe kraamafdeling) (1845)

- Liden Kirsten (Kleine Kirsten) (1846)

- Brylluppet ved Como-Søen (De bruiloft aan het Comomeer) (1849)

- En nat i Roskilde (Een nacht in Roskilde) (1849)

- Meer end Perler og Guld (Meer dan parels en goud) (1849)

- Ole Lukøie (1850)

- Hyldemoer (1851)

- Nøkken (De sleutel) (1853)

- Han er ikke født (Hij is niet geboren) (1864)

Muziek en Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen in 1869Hans Christian Andersen in 1874

Andersen werkte in zijn leven samen met verschillende componisten en was een groot muziekliefhebber. Hij volgde de ontwikkelingen in de muziek met grote interesse. Gedurende zijn reizen ontmoette hij Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann en Richard Wagner. Als ‘theaterman’ had hij met name grote interesse in opera. Hij beschreef Wagners muziek voordat het Deense publiek met diens muziek had kennisgemaakt. Ook na Andersens dood bleef zijn werk vele componisten inspireren; er verschenen diverse balletten en opera’s naar zijn sprookjes en liederen naar zijn gedichten en dat gebeurt ook nu nog. In de jaren 1830 werkte Andersen samen met de bekende Deense componist Christoph Ernst Friedrich Weyse aan het romantisch zangspel Festen pø Kenilworth, dat in 1836 in het Koninklijk Theater van Kopenhagen werd opgevoerd. Een andere componist met wie Andersen samenwerkte was zijn leeftijdgenoot Johan Peter Emilius Hartmann. Deze samenwerking duurde lang en was intensief. Hun eerste werk was de opera Ravnen, eller Broderprøven, een ambitieus werk in drie akten dat in 1832 zijn première beleefde. Andersen baseerde dit werk op een toneelstuk van Carlo Gozzi. Ook de opera Liden Kirsten uit 1844-46 was een resultaat van hun samenwerking.[4] Andersen schreef ook een aantal libretto’s voor opera’s:

- Bruden fra Lammermoor (een bewerking van The Bride of Lammermoor van Walter Scott) voor de componist I.F. Brendal, 1832;

- Ravnen, eller Broderprøven voor J.P.E. Hartmann, 1832;

- Festen på Kenilworth voor C.E.F. Weyse, een romantisch zangspel, 1836;

- Brylluppet ved Como-Søen (de bruiloft aan het Comomeer) voor de Duitse componist Franz Gläser, 1849;

- Nøkken (de watergeest) ook voor de componist Gläser, 1853;

- Liden Kirsten, op. 44, een opera van J.P.E. Hartmann uit 1846.

Muziekwerken geïnspireerd op Andersens werk

Dit is geen volledige lijst.

- Niels W. Gade: Agnete og Havmanden (toneelmuziek), op. 3 (1842)

- August Enna: Den lille pige med svovlstikkerne (opera) (1899)

- Alexander Zemlinsky: Die Seejungfrau (1903)

- Igor Stravinsky: Solovey (Le rossignol) (muzieksprookje) (1908-14) – Pesnya solov’ya (Chant du Rossignol)

- Paul von Klenau: Klein Idas Blumen (ballet naar: Lille Idas blomster) (1916)(symfonisch gedicht / ballet, beide gebaseerd op Nattergalen) [arrangement van Solovey] (1917)

- Charles Villiers Stanford: The travelling Companion, op. 146 (opera, gebaseerd op Rejsekammeraten) (1919)

- Alfred Bruneau: Le jardin du paradis (conte lyrique, gebaseerd op Paradisets have) (1921)

- Alexandre Tansman: Le jardin du paradis (ballet) (1922)

- Florent Schmitt: Le petit elfe ferme-l’oeil, op. 73 (ballet) (1923)

- Nino Rota: Il principe porcaro (opera, gebaseerd op Svinedrengen) (1926)

- Ernst Toch: Die Prinzessin auf der Erbse, op. 43 (opera, gebaseerd op Prinsessen på ærten) (1927)

- Igor Stravinsky: Le baiser de la fée (The fairy’s kiss) (allegorisch ballet) (1928)

- Rudolf Wagner-Régeny: Der nackte König (opera, gebaseerd op Kejserens nye klæder) (1928)

- Louis Glass: Episoder af H. C. Andersens eventyr ‘Elverhøj’, op. 67 (1931)

- Daniel Sternefeld: Mater Dolorosa (opera, gebaseerd op Historien om en moder) (1935)

- Finn Høffding: Det er ganske vist, op. 37 (1940)

- Poul Schierbeck: I Danmark er jeg født, op. 43 (1941)

- Werner Egk: Die chinesische Nachtigall (ballet) (1953)

- Else Marie Pade: De kleine zeemeermin (1958)

- Hans Werner Henze: L’usignolo dell’imperatore (pantomime) (1959)

- Alexandre Tansman: Les habits neufs du roi (ballet) (1959)

- Alun Hoddinott: What the Old Man does is always Right (opera) (1977)

- Søren Hyldgaard: Hans Christian Andersen Suite (for concertband) 1997

- Edward Ferdinand: De Sneeuwkoningin (musical) 2006

- Pet Shop Boys: The Most Incredible Thing (ballet, geïnspireerd op Det Utroligste) (2011)

H.C. Andersen na zijn dood

- In Odense is het Hans Christian Andersen museum te vinden, waarin zijn leven is te volgen. Het huis waarin hij opgroeide is daar ook te bezichtigen.

- Tob de Bordes maakte over zijn bezoeken een NCRV-televisieproductie ‘Andersen in Amsterdam’ in 1975.

- In 2005 opende pretpark De Efteling zijn vijfentwintigste sprookje in het Sprookjesbos: Het meisje met de zwavelstokjes. Eerder waren al De Chinese Nachtegaal, De kleine zeemeermin en De rode schoentjes van Andersen in het sprookjespark te bezichtigen. Sinds 8 november 2012 is ook het sprookje De nieuwe kleren van de keizer te zien.

- Andersen was ook te zien in Nightcap, de 27e aflevering van de Japanse animatieserie Flint the Time Detective.

Literatuur

- Jens Andersen, Hans Christian Andersen. A New Life, 2005. ISBN 9781585677375

- André Roes, Kierkegaard en Andersen, Uitgeverij Aspect, Soesterberg, 2017. ISBN 9789463382151 https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Christian_Andersen

—–

Prinses op de erwt (oorspronkelijke titel: Prindsessen paa Ærten)

is een sprookje van Hans Christian Andersen. Het verscheen voor het eerst in 1835.

Verhaal

Een koning en koningin hebben een zoon die op zoek is naar een prinses. Om er een echte prinses uit te halen, verzinnen ze een list: wie na een nacht slapen op 20 matrassen nog voelt dat er een erwt onder ligt, wegens haar gevoelige huid, kan niet anders dan een prinses zijn.

Na de vele sollicitaties van meisjes die allemaal beweren dat ze een prinses zijn, maar die heerlijk slapen op de 20 matrassen, dient zich op een dag een meisje aan dat er door de regen en storm niet uitziet, maar beweert een prinses te zijn. Ook zij moet dezelfde proef doorstaan en gaat slapen op de 20 matrassen. Als de prinses de volgende morgen verklaart niet geslapen te hebben omdat het leek of er een steen onder haar bed lag, zijn de koning en koningin overtuigd. De prins trouwt met de prinses en ze leven nog lang en gelukkig. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_prinses_op_de_erwt

Concertgebouworkest – Die Seejungfrau – Zemlinsky

Wednesday 27 May we stream Zemlinsky’s Die Seejungfrau, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski. Before the concert, you can watch an interview with Jurowski about the piece. The stream is introduced by clarinettist Hein Wiedijk.

Beschrijving

Het Concertgebouworkest speelt onder leiding van Vladimir Jurowski Die Seejungfrau van Zemlinsky, een muzikale fantasie naar het sprookje De kleine zeemeermin van Hans Christian Andersen.

Die Seejungfrau van Zemlinsky

Die Seejungfrau van Alexander von Zemlinsky is een muzikale fantasie naar het sprookje De kleine zeemeermin van Hans Christian Andersen. Die Seejungfrau opent met een verklanking van de zeebodem en het spel van de zeemeermin. Dan steekt een woeste storm op, waarin de prins schipbreuk leidt en door de zeemeermin wordt gered. De zeemeermin wordt verliefd op de prins, maar die trouwt met iemand anders. Dan verandert de zeemeermin in een eeuwige geest van de lucht.

Vladimir Jurowski, dirigent

De Russische dirigent Vladimir Jurowski was voor het eerst in 2006 te gast bij het Concertgebouworkest. In 2007, na vier jaar als eerste gastdirigent, werd hij chef-dirigent van het London Philharmonic Orchestra. Jurowski is tevens chef-dirigent van het Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, ‘principal artist’ bij het Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment en artistiek leider van het Russisch Staats Symfonieorkest. Vladimir Jurowski leidde als gastdirigent bijvoorbeeld de Berliner Philharmoniker, The Philadelphia Orchestra en het Gewandhausorchester Leipzig.

https://www.concertgebouworkest.nl/nl/zemlinsky-die-seejungfrau

I. Sehr mässig bewegt II. Sehr bewegt, rauschend III. Sehr gedehnt, mit schmerzvollem Ausdruck. Performed by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Riccardo Chailly.

De kleine zeemeermin (Deens: Den lille Havfrue) is een beroemd sprookje van de Deense schrijver Hans Christian Andersen, dat voor het eerst is uitgegeven in 1837.

Het sprookje

Het sprookje van de kleine zeemeermin begint met een beschrijving van de kleur, diepte en weidsheid van de zee. Daarin woont de meermin met haar vader de koning, haar oma en haar 4 oudere zussen. Op haar 15e mag zij, zoals alle meerminnen, naar de oppervlakte zwemmen en de wereld daarboven bekijken. De 5 zussen zijn geboren met 1 jaar tussen ieder, en in de kleinste zeemeermin groeit het verlangen om met haar zusters mee te kunnen naar de oppervlakte zodat ook zij de mensen en hun steden kan zien.

Op haar 15e is het zo ver, zij zwemt naar de oppervlakte. Daar ziet ze een mooie prins op een schip en wordt op slag verliefd op hem. Een heftige storm steekt op en de prins komt bijna om, maar ze weet hem te redden en naar een strand vlak bij een tempel te brengen. Daar laat zij de bewusteloze prins achter.

De kleine zeemeermin blijft naar de prins verlangen, ze verlangt naar het hebben van een ziel en een eeuwig leven na de dood zoals de mensen – in plaats van in schuim op de oppervlakte van de zee te veranderen zoals de meermannen doen.

Ten einde raad gaat ze naar de zeeheks. In ruil voor een toverdrank die haar benen geeft, staat zij haar tong en daardoor haar mooie stem af aan de heks. Het drinken van de toverdrank voelt alsof er een zwaard door haar heen gaat en elke stap die ze op het land zet voelt alsof ze over scherpe messen loopt. De enige manier voor haar om een ziel te krijgen, is zorgen dat de prins van haar houdt en met haar trouwt. Gebeurt dit niet, dan zal ze overlijden en tot schuim op de zee veranderen op de dag dat de prins haar hart breekt door met een andere vrouw te trouwen. Ze drinkt de toverdrank en ontmoet even later de prins. Hij voelt zich aangetrokken door haar schoonheid en haar mooie manier van bewegen. Ze kan niet met hem praten, omdat zij door het afstaan van haar tong stom is geworden. De prins houdt echter van haar zoals iemand van een klein kind houdt.

Op een dag trekt de prins eropuit om een bruid te vinden. Hij gaat naar een van de buurrijken. Daar blijkt de dochter van de koning diegene te zijn die de prins op het strand vond waar de kleine zeemeermin hem achterliet na de storm. De prins wordt verliefd en na een korte tijd kondigt hij de bruiloft aan. Dat breekt het hart van de kleine zeemeermin, en ze wordt wanhopig terwijl de bruiloft nadert.

Haar zusters weten raad, ze geven haar een mes dat ze in ruil voor hun mooie haar bij de zeeheks hebben gekocht. Als de kleine zeemeermin de prins vermoordt met dat mes, kan ze weer een meermin worden en terug naar haar familie gaan voor de rest van haar leven. Dit kan ze niet doen. Ze stort zichzelf in de zee en verandert in schuim.

Zij sterft echter niet, ze wordt een dochter van de lucht die onzichtbaar is voor de mensen. Als ze 300 jaar lang goede daden heeft verricht, heeft ze haar ziel verdiend en komt ze het koninkrijk van de hemelen binnen. Gelukkig mag de dochter van de lucht voor ieder goed kind dat ze vindt een jaar van de 300 aftrekken, maar als ze moet huilen om een kwaad of ondeugend kind, voegt iedere traan een dag toe aan de jaren. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_kleine_zeemeermin

—

Vladimir Jurowski is geboren in Moskou. Daar begon hij ook zijn conservatoriumstudie. Nadat zijn familie in 1990 naar Duitsland verhuisde studeerde hij verder in Dresden en Berlijn. Sinds 2001 is Jurowski zeer succesvol als artistiek directeur van het Glyndebourne Festival Opera. In 2007, na vier jaar als eerste gastdirigent, werd hij chef-dirigent van het London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Daarnaast is Jurowski ‘principal artist’ bij het Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment en artistiek leider van het Russisch Staats Symfonieorkest. Vladimir Jurowski is bij vele grote orkesten van de wereld gastdirigent geweest; zo leidde hij het Berliner Philharmoniker, het Philadelphia Orchestra, de Chicago Symphony en het Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. https://www.concertgebouworkest.nl/nl/zemlinsky-s-die-seejungfrau

—

Alexander (von) Zemlinsky (Wenen, 14 oktober 1871 – Larchmont, New York, 15 maart 1942) was een Oostenrijks–Amerikaans dirigent en componist.

Leven

De vader van Alexander, Adolf von Zemlinsky (1845-1900), heeft zijn katholicisme afgezworen en het jodendom aangenomen om te kunnen trouwen met zijn joodse verloofde Clara Semo (1848-1912), Alexanders toekomstige moeder. De familienaam was van oorsprong Semlinsky, maar is omgezet naar Zemlinsky.

Al op zijn vierde jaar krijgt Alexander zijn eerste pianolessen. Hij speelt al snel op het orgel in de synagoge. In 1884 wordt hij toegelaten op de voorbereidende school voor het Weens conservatorium. Tussen 1887 en 1890 maakt hij zijn eerste – korte – composities. In 1890 wint Zemlinsky de jaarlijkse pianowedstrijd van het conservatorium. Vervolgens studeert hij tot 1892 compositie bij Johann Nepomuk Fuchs en Franz Krenn.

In 1895 vormt Zemlinsky zijn eerste orkest, het amateurorkest Polyhymnia. Hij leidt het bij de eerste optredens. Bij het orkest maakt hij ook kennis met Arnold Schönberg, die hij cellolessen geeft en met wie hij voor de rest van zijn leven bevriend blijft.

In 1899 wordt Zemlinksy benoemd bij het Carltheater, waar hij tot 1904 blijft. Daarna is hij van 1904 tot 1906 dirigent en van 1906 – 1911 chef-dirigent bij de Volksoper. Tegelijk dirigeert hij in 1907 en 1908 ook bij de Hofoper.

In 1899 laat hij zich uitschrijven bij de Joodse gemeenschap in Wenen, later zal hij zich tot het protestantisme bekeren.

In 1907 trouwt Alexander met Ida Guttmann (1880-1929), de jongere zus van zijn eerdere verloofde Melanie. Op 8 mei 1908 wordt dochter Ida geboren. Het huwelijk is niet gelukkig; Alexander zou meerdere relaties hebben buiten zijn huwelijk.

Ontevreden over de mogelijkheden die hem in Wenen geboden worden om zijn muziek en muzikale talenten ten gehore te brengen besluit Zemlinsky te vertrekken. In 1911 wordt hij operadirigent bij het Neues Deutsches Theater in Praag. In 1920 wordt hij daar tevens compositieleraar aan de Deutsche Akademie für Musik.

In 1914 is de veertienjarige Luise Sachsel (1900-1992) zangstudente bij hem. Zij is kunstenares en schildert een portret van hem. Later, in haar twintiger jaren, worden de twee op elkaar verliefd. Vanwege Ida’s slechte gezondheid verlaat Alexander haar niet, maar de relatie met Luise blijft tot aan het eind van zijn leven. De andere buitenechtelijke relaties drogen op.

De volgende stap van Zemlinsky is zijn vertrek naar Berlijn. Hij wordt van 1927 tot 1930 dirigent bij de Kroll-Oper. Op 30 januari 1929 overlijdt Ida. Een jaar later, op 4 januari, trouwen Alexander en Luise.

Van 1930 tot 1933 is Zemlinsky gastdirigent bij de Berlijnse Staatsopera. In 1933 moet hij door de opkomst van het nationaalsocialisme Berlijn ontvluchten. Hij gaat eerst terug naar het relatief veilige Wenen, maar na de Anschluss in 1938 vlucht hij door naar Praag. Na een jaar lang proberen om een visum te krijgen vertrekt hij via Rotterdam naar de Verenigde Staten.

In de Verenigde Staten zijn de Zemlinsky’s onbekende, berooide vluchtelingen. Hij krijgt allerlei gezondheidsklachten. Eerst wordt de familie nog bijgestaan door een broer van Luise in Canada, maar na diens overlijden staat Luise er alleen voor. Kort na het betrekken van een nieuw huis in 1942 overlijdt Alexander aan longontsteking.

Werken

Zemlinsky, leraar en zwager van Arnold Schönberg, had als dirigent grote bewondering voor Brahms en Mahler. De muziek die hij schreef was overwegend laat-romantisch.

Het oeuvre van Zemlinsky omvat een aantal zeer diverse werken:

Opera

- Sarema (1897)

- Es war einmal (1900)

- Der Traumgörge (1904-1906)

- Kleider machen Leute (1910)

- Eine florentinische Tragödie (1917)

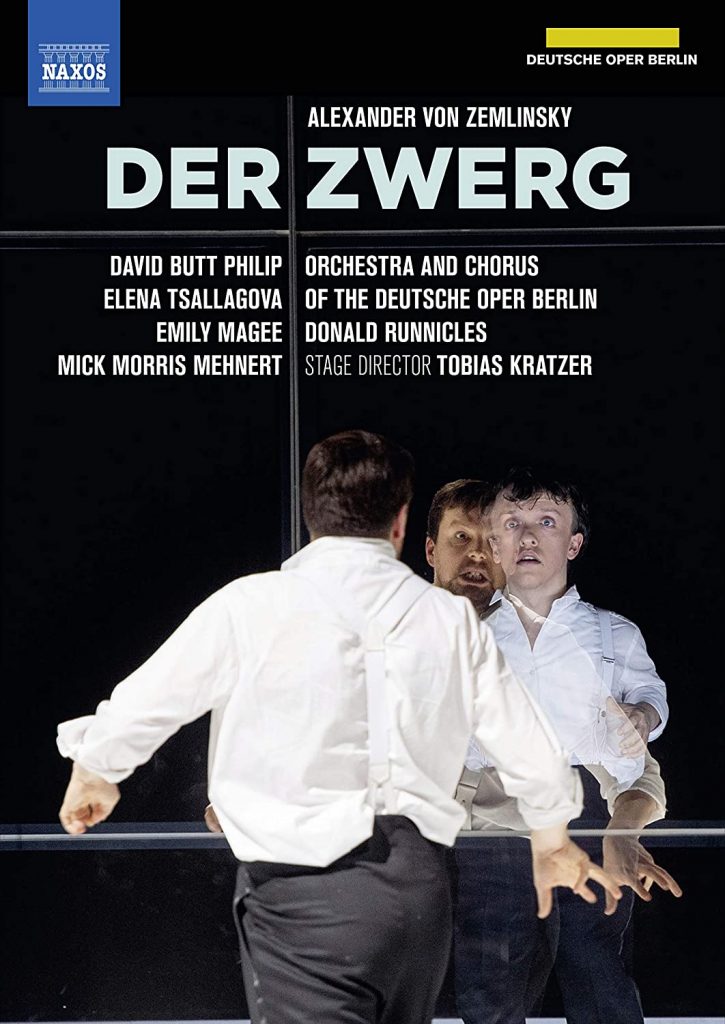

- Der Zwerg (1922)

- Der Kreidekreis (1933)

- Der König Kandaules (1936)

Orkestwerken

- Symfonie no. 1 in e mineur (1891)

- Symfonie no. 2 in d mineur (1892-1893)

- Symfonie no. 3 in B (1896 – 1903) bijgenaamd “Die lyrische”, zeven gezangen voor sopraan- en bariton met orkest naar gedichten van Rabindranath Tagore, op. 18

- Die Seejungfrau (1905), naar het sprookje van Hans Christian Andersen. Dit is naar de vorm een symfonie, maar heeft niet de naam symfonie gekregen.

- Sinfonietta (1934)

Balletmuziek

- Das gläserne Herz (1903)

- Der Triumph der Zeit (1901)

Koorwerken

- Frühlingsbegräbnis (1896)

- Psalm 83 (1900)

- Psalm 23 (1910)

- Psalm 13 (1935)

Kamermuziek

- Pianosonate no. 1 in G groot (1887)

- Pianokwartet in D groot (1893)

- Strijkkwartet in e klein (1893)

- Strijkkwartet in A groot (1914)

- Strijkkwartet no. 3 (1924)

- Strijkkwartet no. 4 (1934)

- Strijkkwintet in D groot (1895)

- Suite in A groot voor piano en viool (1895)

- Pianotrio in D groot (1895)

- Klarinettrio in d klein (1896)

- Trio voor klarinet of altviool, cello en piano

Liederen

- Gesänge (1913)

- Lyrische Symfonie (1924)

- Symfonische Lieder (1929)

Literatuur

- Alfred Clayton: Zemlinsky, Alexander (von), in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie, London, 1992. ISBN 0-333-73432-7

- Antony Beaumont: Zemlinsky. Faber and Faber, London, 2000. ISBN 0-571-16983-X

- Lorraine Gorrell: Discordant Melody – Alexander Zemlinsky, His Songs, and the Second Viennese School. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 2002. ISBN 0313323666 https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Zemlinsky

The visual world of Der Zwerg (part one) – Dutch National Opera

In case you want to support our house and the artists through these uncertain times you can make a donation via this link: http://bit.ly/donation-nob On 4 September, we open our season with Der Zwerg. Get into the mood with this behind the scenes video featuring the beautiful costumes! 🎥🐷 With Alexander Zemlinsky’s opera, based on Oscar Wilde’s fairy tale, our new chief conductor Lorenzo Viotti opens the 21/22 opera season. Der Zwerg is an opera about exclusion based on looks. Watch this video to see how costume designer Wojciech Dziedzic and director Nanouk Leopold transform this notion visually. Check out our website for more information about Der Zwerg: https://www.operaballet.nl/en/dutch-n…

The Spanish crown princess receives a very special present: a little person. To everyone’s amusement, he is unaware of his small stature. Before long feelings develop between the pair, but what chance do they have in a world where appearance is everything? Based on a story by Oscar Wilde, Der Zwerg (The Dwarf) is perhaps Zemlinsky’s best-known and most powerful opera. The performance marks both the first production of rising star Lorenzo Viotti as principal conductor at Dutch National Opera and the operatic debut of film and theatre director Nanouk Leopold. The heldentenor Clay Hilley performs the title role, while Infanta Clara is interpreted by soprano Lenneke Ruiten. Streamed on OperaVision on 18 September 2021 at 19:00 CET and available until 18 December 2021: https://operavision.eu/en/library/per…

…but what chance do they have in a world where appearance is everything…

Synopsis

A sultan has sent a dwarf as a present to the Infanta (Spanish princess) Donna Clara on her birthday. The dwarf is unaware of his physical deformity and becomes infatuated with the Infanta. He sings her a love song and imagines himself her brave knight. She toys with him and gives him a white rose as a present. Left alone, he accidentally uncovers a mirror and sees his own reflection for the first time. In great agitation, he tries to obtain a kiss from the Infanta, but she spurns him and calls him a monster. His heart broken, he dies clutching the white rose as the Infanta rejoins the party. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Der_Zwerg

The Birthday of the Infanta

“The Birthday of the Infanta” is a historical fiction short story for children by the Irish author Oscar Wilde. It was first published in the 1891 anthology House of Pomegranates, which also includes “The Young King‘, “The Fisherman and his Soul” and “The Star-Child“.

The action of “The Birthday of the Infanta” takes place in Spain at an unspecified point in the past. It is the twelfth birthday of the Infanta, the only daughter, and only child, of the King of Spain. For her entertainment, an ugly young dwarf dancer is brought to the court. The Dwarf is completely unaware of how hideous he looks and does not realize that the reason that others laugh in his presence is because they are mocking his appearance. When the Dwarf sees his own reflection for the first time in his life, the consequences are severe.

The Austrian composer Alexander von Zemlinsky adapted the story as the opera Der Zwerg (The Dwarf), which was first performed in 1922.

Plot

The King of Spain has been a widower for nearly twelve years, the Queen having died shortly after their daughter the Infanta was born. The Queen’s death has left the King a deeply melancholy man. He cannot bear to look at his daughter for long because she reminds him too much of her late mother. Consequently, on the day of the Infanta’s twelfth birthday, the King withdraws from the celebrations early, leaving the Infanta in the care of her uncle Don Pedro and other courtiers.

The Infanta is very happy on the day of her birthday. Ordinarily, she is only allowed to play with children of her own rank. Since there are no other royal children in the kingdom, this means that she is usually not allowed to play with anyone else. However, on the day of her birthday she is allowed to invite any children she chooses to the palace. A series of entertainments are arranged for the princess and her guests. The first is a mock bullfight, in which the matadors and the bull are played by boys in costumes. This is followed by a puppet show, choir singers, a magician and Gypsy musicians with a performing bear and monkeys.

Everyone agrees that the best performer of all is a young dancing dwarf. The ugly Dwarf has crooked legs, a hunched back and a large head. Some hunting courtiers had come across him only the day before in a forest. His father, a poor charcoal burner who considered the boy to be useless, was happy to sell him to the courtiers. What makes the Dwarf most appealing to the courtiers is the fact that he is completely unaware of how ugly he is. When children laugh at him, he laughs back just as heartily. At the end of the Dwarf’s performance, the Infanta throws a white rose at him, imitating how she once saw her aunt reward an Italian opera singer. The princess declares that the Dwarf must dance for her again.

When he is told that the Infanta wants him to dance for her again, coupled with the fact that she has already given him a white rose, the Dwarf concludes that she must love him. He goes out into the garden, jumping for joy. He begins to fantasize about a future life with the Infanta, hoping that he can persuade her to come back to the forest with him where he can teach her nature’s secrets. He decides to look for her and goes back inside the palace.

After having passed through several beautiful rooms but having seen no sign of the Infanta, the Dwarf notices a monster at the end of one room. He notices that the monster copies every movement that he makes. He finds that he cannot touch the monster because there is something cold and hard separating him from it. The puzzled Dwarf then notices that everything in the room has a double in the room containing the monster. The horrible realization comes upon the Dwarf that he is looking at his own reflection. He suddenly realizes why other children always laughed in his presence. Understanding that the Infanta does not love him but was mocking him also, he tears the white rose to pieces and falls to the ground sobbing.

The Infanta and her guests come upon the crying Dwarf. They believe that he is merely acting and begin to laugh. The Dwarf gasps, falls silent and becomes still. The princess demands that the Dwarf dance again. Don Pedro threatens to whip him if he does not get up and dance. However, another courtier notices that the Dwarf has died, which he thinks is a pity because the funny Dwarf might have been able to cheer up even the melancholy King. He tells the princess that the Dwarf will never dance again because his heart has broken. To which the Infanta replies,

“For the future, let those who come to play with me have no hearts.” https://literature.fandom.com/wiki/The_Birthday_of_the_Infanta

—–

Oscar Wilde: The Birthday of the Infanta

It was the birthday of the Infanta. She was just twelve years of age, and the sun was shining brightly in the gardens of the palace.

Although she was a real Princess and the Infanta of Spain, she had only one birthday every year, just like the children of quite poor people, so it was naturally a matter of great importance to the whole country that she should have a really line day for the occasion. And a really line day it certainly was. The tall striped tulips stood straight up upon their stalks, like long rows of soldiers, and looked defiantly across the grass at the roses, and said: We are quite as splendid as you are now. The purple butterflies fluttered about with gold dust on their wings, visiting each flower in turn; the little lizards crept out of the crevices of the wall, and lay basking in the white glare; and the pomegranates split and cracked with the heat, and showed their bleeding red hearts. Even the pale yellow lemons, that hung in such profusion from the mouldering trellis and along the dim arcades, seemed to have caught a richer colour from the wonderful sunlight, and the magnolia trees opened their great globe-like blossoms of folded ivory, and filled the air with a sweet heavy perfume.

The little Princess herself walked up and down the terrace with her companions, and played at hide and seek round the stone vases and the old moss-grown statues. On ordinary days she was only allowed to play with children of her own rank, so she had always to play alone, but her birthday was an exception, and the King had given orders that she was to invite any of her young friends whom she liked to come and amuse themselves with her. There was a stately grace about these slim Spanish children as they glided about, the boys with their large-plumed hats and short fluttering cloaks, the girls holding up the trains of their long brocaded gowns, and shielding the sun from their eyes with huge fans of black and silver. But the Infanta was the most graceful of all, and the most tastefully attired, after the somewhat cumbrous fashion of the day. Her robe was of grey satin, the skirt and the wide puffed sleeves heavily embroidered with silver, and the stiff corset studded with rows of fine pearls. Two tiny slippers with big pink rosettes peeped out beneath her dress as she walked. Pink and pearl was her great gauze fan, and in her hair, which like an aureole of faded gold stood out stiffly round her pale little face, she had a beautiful white rose.

From a window in the palace the sad melancholy King watched them. Behind him stood his brother, Don Pedro of Aragon, whom he hated, and his confessor, the Grand Inquisitor of Granada, sat by his side. Sadder even than usual was the King, for as he looked at the Infanta bowing with childish gravity to the assembling courtiers, or laughing behind her fan at the grim Duchess of Albuquerque who always accompanied her, he thought of the young Queen, her mother, who but a short time before – so it seemed to him – had come from the gay country of France, and had withered away in the sombre splendour of the Spanish court, dying just six months after the birth of her child, and before she had seen the almonds blossom twice in the orchard, or plucked the second year’s fruit from the old gnarled fig-tree that stood in the centre of the now grass-grown courtyard. So great had been his love for her that he had not suffered even the grave to hide her from him. She had been embalmed by a Moorish physician, who in return for this service had been granted his life, which for heresy and suspicion of magical practices had been already forfeited, men said, to the Holy Office, and her body was still lying on its tapestried bier in the black marble chapel of the Palace, just as the monks had borne her in on that windy March day nearly twelve years before. Once every month the King, wrapped in a dark cloak and with a muffled lantern in his hand, went in and knelt by her side, calling out, ‘Mi reina! Mi reina!‘ and sometimes breaking through the formal etiquette that in Spain governs every separate action of life, and sets limits even to the sorrow of a King, he would clutch at the pale jewelled hands in a wild agony of grief, and try to wake by his mad kisses the cold painted face.

To-day he seemed to see her again, as he had seen her first at the Castle of Fontainebleau, when he was but fifteen years of age, and she still younger. They had been formally betrothed on that occasion by the Papal Nuncio in the presence of the French King and all the Court, and he had returned to the Escurial bearing with him a little ringlet of yellow hair, and the memory of two childish lips bending down to kiss his hand as he stepped into his carriage. Later on had followed the marriage, hastily performed at Burgos, a small town on the frontier between the two countries, and the grand public entry into Madrid with the customary celebration of high mass at the Church of La Atocha, and a more than usually solemn auto-da-fe, in which nearly three hundred heretics, amongst whom were many Englishmen, had been delivered over to the secular arm to be burned.<3>

Certainly he had loved her madly, and to the ruin, many thought, of his country, then at war with England for the possession of the empire of the New World. He had hardly ever permitted her to be out of his sight: for her, he had forgotten, or seemed to have forgotten, all grave affairs of State; and, with that terrible blindness that passion brings upon its servants, he had failed to notice that the elaborate ceremonies by which he sought to please her did but aggravate the strange malady from which she suffered. When she died he was, for a time, like one bereft of reason. Indeed, there is no doubt but that he would have formally abdicated and retired to the great Trappist monastery at Granada, of which he was already titular Prior, had he not been afraid to leave the little Infanta at the mercy of his brother, whose cruelty, even in Spain, was notorious, and who was suspected by many of having caused the Queen’s death by means of a pair of poisoned gloves that he had presented to her on the occasion of her visiting his castle in Aragon. Even after the expiration of the three years of public mourning that he had ordained throughout his whole dominions by royal edict, he would never suffer his ministers to speak about any new alliance, and when the Emperor himself sent to him, and offered him the hand of the lovely Archduchess of Bohemia, his niece, in marriage, he bade the ambassadors tell their master that the King of Spain was already wedded to Sorrow, and that though she was but a barren bride he loved her better than Beauty; an answer that cost his crown the rich provinces of the Netherlands, which soon after, at the Emperor’s instigation, revolted against him under the leadership of some fanatics of the Reformed Church.

His whole married life, with its fierce, fiery-coloured joys and the terrible agony of its sudden ending, seemed to come back to him to-day as he watched the Infanta playing on the terrace. She had all the Queen’s pretty petulance of manner, the same wilful way of tossing her head, the same proud curved beautiful mouth, the same wonderful smile – vrai sourire de France indeed – as she glanced up now and then at the window, or stretched out her little hand for the stately Spanish gentlemen to kiss. But the shrill laughter of the children grated on his ears, and the bright pitiless sunlight mocked his sorrow, and a dull odour of strange spices, spices such as embalmers use, seemed to taint – or was it fancy? – the clear morning air. He buried his face in his hands, and when the Infanta looked up again the curtains had been drawn, and the King had retired.<4>

She made a little moue of disappointment, and shrugged her shoulders. Surely he might have stayed with her on her birthday. What did the stupid State-affairs matter? Or had he gone to that gloomy chapel, where the candles were always burning, and where she was never allowed to enter? How silly of him, when the sun was shining so brightly, and everybody was so happy! Besides, he would miss the sham bull-fight for which the trumpet was already sounding, to say nothing of the puppet show and the other wonderful things. Her uncle and the Grand Inquisitor were much more sensible. They had come out on the terrace, and paid her nice compliments. So she tossed her pretty head, and taking Don Pedro by the hand, she walked slowly down the steps towards a long pavilion of purple silk that had been erected at the end of the garden, the other children following in strict order of precedence, those who had the longest names going first.

A procession of noble boys, fantastically dressed as toreadors, came out to meet her, and the young Count of Tierra-Nueva, a wonderfully handsome lad of about fourteen years of age, uncovering his head with all the grace of a born hidalgo and grandee of Spain, led her solemnly in to a little gilt and ivory chair that was placed on a raised da’s above the arena. The children grouped themselves all round, fluttering their big fans and whispering to each other, and Don Pedro and the Grand Inquisitor stood laughing at the entrance. Even the Duchess – the Camerera-Mayor as she was called – a thin, hard-featured woman with a yellow ruff did not look quite so bad-tempered as usual, and something like a chill smile flitted across her wrinkled face and twitched her thin bloodless lips.

It certainly was a marvellous bullfight, and much nicer, the Infanta thought, than the real bull-fight that she had been brought to see at Seville, on the occasion of the visit of the Duke of Parma to her father. Some of the boys pranced about on richly-caparisoned hobby-horses brandishing long javelins with gay streamers of bright ribands attached to them; others went on foot waving their scarlet cloaks before the bull, and vaulting lightly over the barrier when he charged them; and as for the bull himself he was just like a live bull, though he was only made of wicker-work and stretched hide, and sometimes insisted on running round the arena on his hind legs, which no live bull ever dreams of doing. He made a splendid fight of it too, and the children got so excited that they stood up upon the benches, and waved their lace handkerchiefs and cried out: Bravo toro! Bravo toro! just as sensibly as if they had been grown-up people. At last, however, after a prolonged combat, during which several of the hobby-horses were gored through and through, and their riders dismounted, the young Count of Tierra-Nueva brought the bull to his knees, and having obtained permission from the Infanta to give the coup de grace, he plunged his wooden sword into the neck of the animal with such violence that the head came right off and disclosed the laughing face of little Monsieur de Lorraine, the son of the French Ambassador at Madrid.<5>

The arena was then cleared amidst much applause, and the dead hobby-horses dragged solemnly away by two Moorish pages in yellow and black liveries, and after a short interlude, during which a French posture-master performed upon the tight rope, some Italian puppets appeared in the semi-classical tragedy of Sophonisba on the stage of a small theatre that had been built up for the purpose. They acted so well, and their gestures were so extremely natural, that at the close of the play the eyes of the Infanta were quite dim with tears. Indeed some of the children really cried, and had to be comforted with sweetmeats, and the Grand Inquisitor himself was so affected that he could not help saying to Don Pedro that it seemed to him intolerable that things made simply out of wood and coloured wax, and worked mechanically by wires, should be so unhappy and meet with such terrible misfortunes. An African juggler followed, who brought in a large flat basket covered with a red cloth, and having placed it in the centre of the arena, he took from his turban a curious reed pipe, and blew through it. In a few moments the cloth began to move, and as the pipe grew shriller and shriller two green and gold snakes put out their strange wedge-shaped heads and rose slowly up, swaying to and fro with the music as a plant sways in the water. The children, however, were rather frightened at their spotted hoods and quick darting tongues, and were much more pleased when the juggler made a tiny orange-tree grow out of the sand and bear pretty white blossoms and clusters of real fruit; and when he took the fan of the little daughter of the Marquess de Las-Torres, and changed it into a blue bird that flew all round the pavilion and sang, their delight and amazement knew no bounds. The solemn minuet, too, performed by the dancing boys from the church of Nuestra Senora Del Pilar, was charming. The Infanta had never before seen this wonderful ceremony which takes place every year at May-time in front of the high altar of the Virgin, and in her honour; and indeed none of the royal family of Spain had entered the great cathedral of Saragossa since a mad priest, supposed by many to have been in the pay of Elizabeth of England, had tried to administer a poisoned wafer to the Prince of the Asturias. So she had known only by hearsay of ‘Our Lady’s Dance,’ as it was called, and it certainly was a beautiful sight. The boys wore old-fashioned court dresses of white velvet, and their curious three-cornered hats were fringed with silver and surmounted with huge plumes of ostrich feathers, the dazzling whiteness of their costumes, as they moved about in the sunlight, being still more accentuated by their swarthy faces and long black hair. Everybody was fascinated by the grave dignity with which they moved through the intricate figures of the dance, and by the elaborate grace of their slow gestures, and stately bows, and when they had finished their performance and doffed their great plumed hats to the Infanta, she acknowledged their reverence with much courtesy, and made a vow that she would send a large wax candle to the shrine of Our Lady of Pilar in return for the pleasure that she had given her.<6>

A troop of handsome Egyptians – as the gipsies were termed in those days – then advanced into the arena, and sitting down cross-legs, in a circle, began to play softly upon their zithers, moving their bodies to the tune, and humming, almost below their breath, a low dreamy air. When they caught sight of Don Pedro they scowled at him, and some of them looked terrified, for only a few weeks before he had had two of their tribe hanged for sorcery in the marketplace at Seville, but the pretty Infanta charmed them as she leaned back peeping over her fan with her great blue eyes, and they felt sure that one so lovely as she was could never be cruel to anybody. So they played on very gently and just touching the cords of the zithers with their long pointed nails, and their heads began to nod as though they were falling asleep. Suddenly, with a cry so shrill that all the children were startled and Don Pedro’s hand clutched at the agate pommel of his dagger, they leapt to their feet and whirled madly round the enclosure beating their tambourines, and chaunting some wild love-song in their strange guttural language. Then at another signal they all flung themselves again to the ground and lay there quite still, the dull strumming of the zithers being the only sound that broke the silence. After that they had done this several times, they disappeared for a moment and came back leading a brown shaggy bear by a chain, and carrying on their shoulders some little Barbary apes. The bear stood upon his head with the utmost gravity, and the wizened apes played all kinds of amusing tricks with two gipsy boys who seemed to be their masters, and fought with tiny swords, and tired off guns, and went t!trough a regular soldier’s drill just like the King’s own bodyguard. In fact the gipsies were a great success.

But the funniest part of the whole morning’s entertainment, was undoubtedly the dancing of the little Dwarf. When he stumbled into the arena, waddling on his crooked legs and Wagging his huge misshapen head from side to side, the children went off into a loud shout of delight, and the Infanta herself laughed so much that the Camerera was obliged to remind her that although there were many precedents in Spain for a King’s daughter weeping before her equals, there were none for a Princess of the blood royal making so merry before those who were her inferiors in birth. The Dwarf however, was really quite irresistible, and even at the Spanish Court, always noted for its cultivated passion for the horrible, so fantastic a little monster had never been seen. It was his first appearance, too. He had been discovered only the day before, running wild through the forest, by two of the nobles who happened to have been hunting in a remote part of the great cork-wood that surrounded the town, and had been carried off by them to the Palace as a surprise for the Infanta, his father, who was a poor charcoal-burner, being but too well pleased to get rid of so ugly and useless a child. Perhaps the most amusing thing about him was his complete unconsciousness of his own grotesque appearance. Indeed he seemed quite happy and full of the highest spirits. When the children laughed, he laughed as freely and as joyously as any of them, and at the close of each dance he made them each the funniest of bows, smiling and nodding at them just as if he was really one of themselves, and not a little misshapen thing that Nature, in some humourous mood, had fashioned for others to mock at. As for the Infanta, she absolutely fascinated him. He could not keep his eyes off her, and seemed to dance for her alone, and when at the close of the performance, remembering how she had seen the great ladies of the Court throw bouquets to Caffarelli the famous Italian treble, whom the Pope had sent from his own chapel to Madrid that he might cure the King’s melancholy by the sweetness of his voice, she took out of her hair the beautiful white rose, and partly for a jest and partly to tease the Camerera, threw it to him across the arena with her sweetest smile, he took the whole matter quite seriously, and pressing the flower to his rough coarse lips he put his hand upon his heart, and sank on one knee before her, grinning from ear to ear, and with his little bright eyes sparkling with pleasure.

This so upset the gravity of the Infanta that she kept on laughing long after the little Dwarf had run out of the arena, and expressed a desire to her uncle that the dance should be immediately repeated. The Camerera, however, on the plea that the sun was too hot, decided that it would be better that her Highness should return without delay to the Palace, where a wonderful feast had been already prepared for her, including a real birthday cake with her own initials worked all over it in painted sugar and a lovely silver flag waving from the top. The Infanta accordingly rose up with much dignity, and having given orders that the little dwarf was to dance again for her after the hour of siesta, and conveyed her thanks to the young Count of Tierra-Nueva for his charming reception, she went back to her apartments, the children following in the same order in which they had entered.

Now when the little Dwarf heard that he was to dance a second time before the Infanta, and by her own express command, he was so proud that he ran out into the garden, kissing the white rose in an absurd ecstasy of pleasure, and making the most uncouth and clumsy gestures of delight.

The Flowers were quite indignant at his daring to intrude into their beautiful home, and when they saw him capering up and down the walks, and waving his arms above his head in such a ridiculous manner, they could not restrain their feelings any longer.

‘He is really far too ugly to be allowed to play in any place where we are,’ cried the Tulips.

‘He should drink poppy-juice, and go to sleep for a thousand years,’ said the great scarlet Lilies, and they grew quite hot and angry.

‘He is a perfect horror!’ screamed the Cactus. ‘Why, he is twisted and stumpy, and his head is completely out of proportion with his legs. Really he makes me feel prickly all over, and if he comes near me I will sting him with my thorns.’<8>

‘And he has actually got one of my best blooms,’ exclaimed the White Rose-Tree. ‘I gave it to the Infanta this morning myself as a birthday present, and he has stolen it from her.’ And she called out: ‘Thief thief thief!’ at the top of her voice.

Even the red Geraniums, who did not usually give themselves airs, and were known to have a great many poor relations themselves, curled up in disgust when they saw him, and when the Violets meekly remarked that though he was certainly extremely plain, still he could not help it, they retorted with a good deal of justice that that was his chief defect, and that there was no reason why one should admire a person because he was incurable; and, indeed, some of the Violets themselves felt that the ugliness of the little Dwarf was almost ostentatious, and that he would have shown much better taste if he had looked sad, or at least pensive, instead of jumping about merrily, and throwing himself into such grotesque and silly attitudes.

As for the old Sundial, who was an extremely remarkable individual, and had once told the time of day to no less a person than the Emperor Charles V himself, he was so taken aback by the little Dwarf’s appearance, that he almost forgot to mark two whole minutes with his long shadowy finger, and could not help saying to the great milk-white Peacock, who was sunning herself on the balustrade, that everyone knew that the children of Kings were Kings, and that the children of charcoal-burners were charcoal-burners, and that it was absurd to pretend that it wasn’t so; a statement with which the Peacock entirely agreed, and indeed screamed out, ‘Certainly, certainly,’ in such a loud, harsh voice, that the gold-fish who lived in the basin of the cool splashing fountain put their heads out of the water, and asked the huge stone Tritons what on earth was the matter.

But somehow the Birds liked him. They had seen him often in the forest, dancing about like an elf after the eddying leaves, or crouched up in the hollow of some old oak-tree, sharing his nuts with the squirrels. They did not mind his being ugly, a bit. Why, even the nightingale herself, who sang so sweetly in the orange groves at night that sometimes the Moon leaned down to listen, was not much to look at after all; and, besides, he had been kind to them, and during that terribly bitter winter, when there were no berries on the trees, and the ground was as hard as iron, and the wolves had come down to the very gates of the city to look for food, he had never once forgotten them, but had always given them crumbs out of his little hunch of black bread, and divided with them whatever poor breakfast he had.<9>

So they flew round and round him, just touching his cheek with their wings as they passed, and chattered to each other, and the little Dwarf was so pleased that he could not help showing them the beautiful white rose, and telling them that the Infanta herself had given it to him because she loved him.

They did not understand a single word of what he was saying, but that made no matter, for they put their heads on one side, and looked wise, which is quite as good as understanding a thing, and very much easier.

The Lizards also took an immense fancy to him, and when he grew tired of running about and flung himself down on the grass to rest, they played and romped all over him, and tried to amuse him in the best way they could. ‘Every one cannot be as beautiful as a lizard,’ they cried; ‘that would be too much to expect. And, though it sounds absurd to say so, he is really not so ugly after all, provided, of course, that one shuts one’s eyes, and does not look at him.’ The Lizards were extremely philosophical by nature, and often sat thinking for hours and hours together, when there was nothing else to do, or when the weather was too rainy for them to go out.

The Flowers, however, were excessively annoyed at their behaviour, and at the behaviour of the birds. ‘It only shows, they said, ‘what a vulgarising effect this incessant rushing and flying about has. Well-bred people always stay exactly in the same place, as we do. No one ever saw us hopping up and down the walks, or galloping madly through the grass after dragon-flies. When we do want change of air, we send for the gardener, and he carries us to another bed. This is dignified, and as it should be. But birds and lizards have no sense of repose, and indeed birds have not even a permanent address. They are mere vagrants like the gipsies, and should be treated in exactly the same manner.’ So they put their noses in the air, and looked very haughty, and were quite delighted when after some time they saw the little Dwarf scramble up from the grass, and make his way across the terrace to the palace.<10>

‘He should certainly be kept indoors for the rest of his natural life,’ they said. ‘Look at his hunched back, and his crooked legs,’ and they began to titter.

But the little Dwarf knew nothing of all this. He liked the birds and the lizards immensely, and thought that the flowers were the most marvellous things in the whole world, except of course the Infanta, but then she had given him the beautiful white rose, and she loved him, and that made a great difference. How he wished that he had gone back with her! She would have put him on her right hand, and smiled at him, and he would have never left her side, but would have made her his playmate, and taught her all kinds of delightful tricks. For though he had never been in a palace before, he knew a great many wonderful things. He could make little cages out of rushes for the grasshoppers to sing in, and fashion the long-jointed bamboo into the pipe that Pan loves to hear. He knew the cry of every bird, and could call the starlings from the tree-top, or the heron from the mere. He knew the trail of every animal, and could track the hare by its delicate footprints, and the boar by the trampled leaves. All the wind-dances he knew, the mad dance in red raiment with the autumn, the light dance in blue sandals over the corn, the dance with white snow-wreaths in winter, and the blossom-dance through the orchards in spring. He knew where the wood-pigeons built their nests, and once when a fowler had snared the parent birds, he had brought up the young ones himself, and had built a little dovecote for them in the cleft of a pollard elm. They were quite tame, and used to feed out of his hands every morning. She would like them, and the rabbits that scurried about in the long fern, and the jays with their steely feathers and black bills, and the hedgehogs that could curl themselves up into prickly balls, and the great wise tortoises that crawled slowly about, shaking their heads and nibbling at the young leaves. Yes, she must certainly come to the forest and play with him. He would give her his own little bed, and would watch outside the window till dawn, to see that the wild horned cattle did not harm her, nor the gaunt wolves creep too near the hut. And at dawn he would tap at the shutters and wake her, and they would go out and dance together all the day long. It was really not a bit lonely in the forest. Sometimes a Bishop rode through on his white mule, reading out of a painted book. Sometimes in their green velvet caps, and their jerkins of tanned deerskin, the falconers passed by, with hooded hawks on their wrists. At vintage time came the grape-treaders, with purple hands and feet, wreathed with glossy ivy and carrying dripping skins of wine; and the charcoal-burners sat round their huge braziers at night, watching the dry logs charring slowly in the fire, and roasting chestnuts in the ashes, and the robbers came out of their caves and made merry with them. Once, too, he had seen a beautiful procession winding up the long dusty road to Toledo. The monks went in front singing sweetly, and carrying bright banners and crosses of gold, and then, in silver armour, with matchlocks and pikes, came the soldiers, and in their midst walked three barefooted men, in strange yellow dresses painted all over with wonderful figures, and carrying lighted candles in their hands. Certainly there was a great deal to look at in the forest, and when she was tired he would find a soft bank of moss for her, or carry her in his arms, for he was very strong, though he knew that he was not tall. He would make her a necklace of red bryony berries, that would be quite as pretty as the white berries that she wore on her dress, and when she was tired of them, she could throw them away, and he would find her others. He would bring her acorn-cups and dew-drenched anemones, and tiny glow-worms to be stars in the pale gold of her hair.

But where was she? He asked the white rose, and it made him no answer. The whole palace seemed asleep, and even where the shutters had not been closed, heavy curtains had been drawn across the windows to keep out the glare. He wandered all round looking for some place through which he might gain an entrance, and at last he caught sight of a little private door that was lying open. He slipped through, and found himself in a splendid hall, far more splendid, he feared, than the forest, there was so much more gilding everywhere, and even the floor was made of great coloured stones, fitted together into a sort of geometrical pattern. But the little Infanta was not there, only some wonderful white statues that looked down on him from their jasper pedestals, with sad blank eyes and strangely smiling lips.

At the end of the hall hung a richly embroidered curtain of black velvet, powdered with suns and stars, the King’s favourite devices, and broidered on the colour he loved best. Perhaps she was hiding behind that? He would try at any rate.

So he stole quietly across, and drew it aside. No; there was only another room, though a prettier room, he thought, than the one he had just left. The walls were hung with a many-figured green arras of needle-wrought tapestry representing a hunt, the work of some Flemish artists who had spent more than seven years in its composition. It had once been the chamber of Jean le Fou, as he was called, that mad King who was so enamoured of the chase, that he had often tried in his delirium to mount the huge rearing horses, and to drag down the stag on which the great hounds were leaping, sounding his hunting horn, and stabbing with his dagger at the pale flying deer. It was now used as the council-room, and on the centre table were lying the red portfolios of the ministers, stamped with the gold tulips of Spain, and with the arms and emblems of the house of Hapsburg.

The little Dwarf looked in wonder all round him, and was half-afraid to go on. The strange silent horsemen that galloped so swiftly through the long glades without making any noise, seemed to him like those terrible phantoms of whom he had heard the charcoal-burners speaking – the Comprachos, who hunt only at night, and if they meet a man, turn him into a hind, and chase him. But he thought of the pretty Infanta, and took courage. He wanted to find her alone, and to tell her that he too loved her. Perhaps she was in the room beyond.<12>

He ran across the soft Moorish carpets, and opened the door. No! She was not here either. The room was quite empty.

It was a throne-room, used for the reception of foreign ambassadors, when the King, which of late had riot been often, consented to give them a personal audience; the same room in which, many years before, envoys had appeared from England to make arrangements for the marriage of their Queen, then one of the Catholic sovereigns of Europe, with the Emperor’s eldest son. The hangings were of gilt Cordovan leather, and a heavy gilt chandelier with branches for three hundred wax lights hung down from the black and white ceiling. Under-neath a great canopy of gold cloth, on which the lions and towers of Castile were broidered in seed pearls, stood the throne itself covered with a rich pall of black velvet studded with silver tulips and elaborately fringed with silver and pearls. On the second step of the throne was placed the kneeling-stool of the Infanta, with its cushion of cloth of silver tissue, and below that again, and beyond the limit of the canopy, stood the chair for the Papal Nuncio, who alone had the right to be seated in the King’s presence on the occasion of any public ceremonial, and whose Cardinal’s hat, with its tangled scarlet tassels, lay on a purple tabouret in front. On the wall, facing the throne, hung a life-sized portrait of Charles V in hunting dress, with a great mastiff by his side, and a picture of Philip II receiving the homage of the Netherlands occupied the centre of the other wall. Between the windows stood a black ebony cabinet, inlaid with plates of ivory, on which the figures from Holbein’s Dance of Death had been graved – by the hand, some said, of that famous master himself.

But the little Dwarf cared nothing for all this magnificence. He would not have given his rose for all the pearls on the canopy, nor one white petal of his rose for the throne itself What he wanted was to see the Infanta before she went down to the pavilion, and to ask her to come away with him when he had finished his dance. Here, in the Palace, the air was close and heavy, but in the forest the wind blew free, and the sunlight with wandering hands of gold moved the tremulous leaves aside. There were flowers, too, in the forest, not so splendid, perhaps, as the flowers in the garden, but more sweetly scented for all that; hyacinths in early spring that flooded with waving purple the cool glens, and grassy knolls; yellow primroses that nestled in little clumps round the gnarled roots of the oak-trees; bright celandine, and blue speedwell, and irises lilac and gold. There were grey catkins on the hazels, and the fox-gloves drooped with the weight of their dappled bee-haunted cells. The chestnut had its spires of white stars, and the hawthorn its pallid moons of beauty. Yes: surely she would come if he could only find her! She would come with him to the fair forest, and all day long he would dance for her delight. A smile lit up his eyes at the thought and he passed into the next room.<13>

Of all the rooms this was the brightest and the most beautiful. The walls were covered with a pink-flowered Lucca damask, patterned with birds and dotted with dainty blossoms of silver; the furniture was of massive silver, festooned with florid wreaths, and swinging Cupids; in front of the two large fire-places stood great screens broidered with parrots and peacocks, and the floor, which was of sea-green onyx, seemed to stretch far away into the distance. Nor was he alone. Standing under the shadow of the doorway, at the extreme end of the room, he saw a little figure watching him. His heart trembled, a cry of joy broke from his lips, and he moved out into the sunlight. As he did so, the figure moved out also, and he saw it plainly.