John Button (born 9 February 1944 in Liverpool, England) is a Western Australian man who was the victim of a significant miscarriage of justice. Button was wrongfully convicted of the manslaughter, by vehicle impact, of his girlfriend, Rosemary Anderson, in 1963. The conviction was quashed in 2002.

Vindication

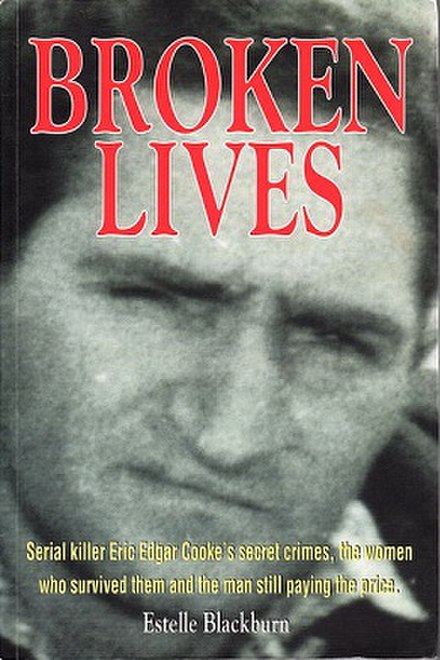

Several appeals to courts or for ministerial intervention were unsuccessful. In 1998, a Western Australian journalist, Estelle Blackburn, advanced the cause of Button’s vindication through her book Broken Lives Following the book’s publication, the matter went before the courts again with Button represented by Tom Percy QC and Jonathan Davies both of whom worked pro bono on the case.

At the original trial the strongest evidence apart from Button’s confession was that his 1962 Simca P60 Aronde sedan had damage consistent with an accident. Trevor Condron was the police officer who had examined John Button’s Simca in 1963 but he had not been asked what could have caused the damage at the trial. He told the appeals court that while the car was damaged, the damage was not consistent with hitting a person and that three weeks before Anderson’s death, Button had reported to police an accident with a Ford Prefect that had caused matching damage to that seen by Condron. This accident report had been known to police at the original trial but been discounted as irrelevant. The court also heard from Dr Neil Turner who had treated Anderson. He claimed that her injuries were not consistent with Button’s vehicle. The world’s leading pedestrian accident expert, American William “Rusty” Haight, was flown to Australia and testified that experiments with a biomedical human-form dummy, three Simca P60 sedans similar to that owned by John Button and a 1961/62 Holden EK sedan similar to the one serial killer Eric Edgar Cooke claimed he was driving when he hit Anderson, matched exactly Cooke’s account and excluded the Simca.

Button self-published a book in 1998 titled “Why Me Lord!” which told of his ordeal.

On 25 February 2002, the Court of Criminal Appeal quashed Button’s conviction after evidence from vehicle crash experts proved that Cooke was most likely the culprit In a televised interview six months after Button’s conviction was quashed, Rosemary Anderson’s parents refused to embrace the finding and still maintained that Cooke did not kill their daughter and that Button was guilty. A conference between the Button, Anderson and Cooke families, Blackburn and her publisher Bret Christian organized by Australian Story changed their minds, although Mrs Anderson maintained Button was still responsible as it was his role as her escort on the night to bring her home. Following a meeting with the W.A. Director of Public Prosecutions to discuss the court’s findings, the Andersons accepted Button’s innocence was proven.

Button now spearheads the Western Australian Innocence Project which aims to free the wrongfully convicted. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Button_(campaigner)

—–

In 1963, Australian teenager John Button is accused of running down his girlfriend on the roadway after a fight. After a brutal police interrogation he confesses, than recants. He is tried and convicted of manslaughter, sentenced to a primitive Victorian-era prison. He regains his physical freedom, but is branded a guilty man. Almost forty years later, a writer uncovers evidence that another man, a known serial killer, might really be responsible. In fact, he had confessed. An accident reconstruction expert tracks down antique cars to re-create the accident, and clear a man’s name decades after a cruel injustice.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0840511/plotsummary?ref_=tt_ov_pl

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0840511/?ref_=ttpl_pl_tt

—-

Broken Lives was written by Estelle Blackburn between 1992 and 1998. The book is about the false imprisonment of two people, John Button and Darryl Beamish who were both convicted for murders that were later proved to be committed by Eric Cooke the last man hanged in Western Australia in the Fremantle Gaol.

Though the information was to go into a book it became a combined exercise in authorship and citizen advocacy which led to the re-opening of the cases of both Button and Darryl Beamish and the quashing of their long-standing convictions.

Background

In 1963 John Button was convicted of the manslaughter of his girlfriend, Rosemary Anderson. Button was originally charged with wilful murder but the jury found him guilty of the lesser charge and was sentenced to 10 years jail. Button’s brother approached Blackburn in January 1992 claiming his older brother had been framed for a murder committed by Eric Cooke, though skeptical Blackburn met John Button in February 1992. After hearing his testimony and reading the appeal books kept from his previous court actions, she decided that his case would be an appropriate topic for the book.

The key discovery in the revision of the case histories was that Eric Cooke had been a multiple-method killer. His offences show a significant deviation from the pattern generally accepted as the orthodox “serial killer” template, which holds that such killers target the same type of victim in the same way, impelled by the same underlying motive. Cooke, conversely, for differing reasons, using various methods, killed or attempted to kill persons of both sexes and of a wide spread of ages and social circumstances.Justice for Button and Beamish: Darryl Beamish, Estelle Blackburn and John Button at the Supreme Court celebrating Beamish’s exoneration on 1 April 2005 (44 years after conviction), following Button’s exoneration on 25 February 2002 (39 years after conviction).

Blackburn discovered, once granted access to police archives, that the police had not emphasised this behaviour pattern of Cooke in their public statements. They made no public announcement that Cooke had attacked seven other women in five hit-runs and five other women asleep in their beds, women who survived the attacks. So the Western Australian community at large and the legal advocates for Button and Beamish were unaware that Cooke had attempted murder by vehicle impact. This was the means by which John Button’s girlfriend, 17-year-old Rosemary Anderson, had been killed. At the time of Button’s trial for her wilful murder, her death appeared to be an isolated event and his claim that he had coincidentally discovered her after the attack seemed implausible. Likewise, during Darryl Beamish’s trial for the wilful murder of 22-year-old heiress Jillian Brewer (who was attacked while she slept), the offence was not placed in the context of the series of assaults that Cooke had committed against other women asleep in their homes.

The location and interviewing of the other, surviving, victims of Cooke and the creation of a detailed analysis of his life and criminal career produced the narrative history, “Broken Lives”. This work had a powerful impact on the public discourse about jurisprudence in Western Australia and the process of completing it created relationships between justice advocates in the fields of journalism and the legal profession which provided the impetus for a renewed campaign to clear Button and Beamish.

Following the initial publication of Broken Lives in 1998, Blackburn became the recipient of a number of awards, the most significant being the Medal of the Order of Australia, a Walkley Award for the greatest contribution to journalism, and induction into the Western Australian Women’s Hall of Fame. Renewed public interest in the cases led to several appearances in the electronic media, including on ABC Television‘s high-profile programme, Australian Story. This increased media profile afforded an opportunity to engage in paid public speaking and invitations to contribute to true-crime anthologies.

Blackburn also assisted in the preparation of the appeal cases for John Button and Darryl Beamish and acted as media liaison for the defence team during the preparation for and hearing of the appeals. In 2002, this epic story of Western Australian jurisprudence, begun with the events of the late 1950s and early 1960s, approached its conclusion: the conviction of John Button for manslaughter was quashed. Darryl Beamish’s wilful murder conviction was quashed in 2005. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broken_Lives

Medical Detectives – Geheimnisse der Gerichtsmedizin – Suche nach Wahrheit / Forensic Files – S08E36 Dueling Confessions – Traces of Truth

Het zou kunnen dat dit ‘m is….. (niet nagekeken) 🙂

Dead unlucky: The John Button story

John Button waited nearly 25 years to prove his innocence.

When he was 18-years-old, John Button had everything a teenage boy in early 1960s Australia could want; a steady job, an enviable car and a devoted girlfriend. But on the night of his 19th birthday, that safe, predictable world would be shattered forever.

What really happened on that hot February night in 1963 in Perth?

It would take nearly half a century to find out, and for John Button, a wrongful conviction and five years in prison.

Today, at the age of 73, John Button is still haunted by the surreal cascade of events that began with the hit-and-run event which left his 17-year-old girlfriend dead.

Special thanks to Val Buchanan and the Supreme Court of Western Australia, for permission to use the original Button trial tapes (Button v The Queen, 22 May 1964).

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/earshot/wrongful-the-john-button-story/9065942

https://abcmedia.akamaized.net/rn/podcast/2017/12/eot_20171225.mp3

A serial killer’s voice from the grave

Eric Edgar Cooke brutally murdered at least eight people in Perth between 1959 and 1963. In original sound recordings unearthed from his trial, he reveals the dark power inside his head that pushed him to unspeakable acts.

By Tracey Stewart Updated 31 May 2021, 5:17am

It was a straightforward news report that gave no indication of the scale of the revelations that were to come.

“In Perth today, a youth was arrested and charged with wilfully murdering a young girl by running her down with a car in Shenton Park last night,” the ABC newsreader told viewers on February 10, 1963.

Rosemary Anderson’s death was one of a series of horrific killings whose dots were yet to be joined to serial killer Eric Edgar Cooke.

It was also one in a series of devastating miscarriages of justice.

The subsequent conviction of Ms Anderson’s boyfriend, John Button, for her manslaughter would become a significant chapter in a saga of wrongful convictions in Western Australia which is explored in the new ABC podcast series ‘Wrongful’, produced by broadcaster Susan Maushart.

Wake-up call for sleepy city

It was a big year for news in 1963.

US President John F Kennedy was assassinated, Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech, the audacious Great Train Robbery was carried out in the UK, and Beatlemania began in earnest.PHOTO: John F Kennedy’s motorcade in Dallas, Texas before his assassination.(Walt Cisco, Dallas Morning News)

Perth, however, seemed a world away from such momentous events and was largely viewed from afar as a sleepy backwater.

But the remote city was about to get a wake-up call.

On Australia Day in 1963 Eric Edgar Cooke terrorised the city in a murderous rampage, randomly shooting five people and killing three.

The residents of Perth were paralysed with fear as police implored them to lock their doors and cars.

What was not known at that time was that Cooke was a multiple murderer responsible for numerous attacks.

The city’s first known serial killer, Cooke eventually became the last man hanged in WA.

It was not until September 1963 that he was charged with murder — that of university student Shirley McLeod, who was shot dead at a house in Dalkeith in August. The error in the ABC TV news report on the day, which named him as Derek Edgar Cooke, belies the monstrous notoriety he would soon acquire.

Killer’s voice from beyond the grave

Maushart’s research into the crimes and punishment of Cooke led her to the Supreme Court in Perth, where she unearthed the original sound recordings of his trial, including testimony from Cooke himself, which had laid undisturbed for decades.

The badly degraded tapes were stretched and deteriorating, and required many hours of expert restoration to make them audible — but they provide a chilling insight into a series of crimes about which Cooke is remarkably candid.

Testifying in court about his Australia Day murder spree in 1963, Cooke — who was born with a cleft lip and palate — speaks in a soft voice that is at times difficult to understand, telling of how he’d spent the morning helping around the house and playing with his children.

“And what happened then?” a detective asks.

“It was then that this power came over me. It wasn’t an impulse, it was stronger than an impulse,” Cooke says.

It was, it was as though I was God and … it was like a mantle or like a cloud came over me, and I must, I must use that.

A massive, random crime spree

Cooke was known to authorities as a petty criminal, primarily a prowler and a thief, so police were incredulous when he confessed to eight murders, 14 attempted murders and the break-and-enter of more than 250 homes.

His murderous spree was mostly random and he killed in many ways, including shooting, strangling and running his victims down with a car.

It was, in part, the seemingly random selection of victims and varied methods of assault that kept police from making the connection between his many victims.

They were also reluctant to believe some of Cooke’s confessions. Not only was he known to them as a consummate liar, but other men had also been tried and convicted of some of his crimes.

This monumental failure of the police to connect Cooke to his catalogue of crimes meant two innocent men spent decades in prison, wrongfully convicted of crimes Cooke had committed.

On February 9, 1963, John Button was celebrating his 19th birthday with his 17-year-old girlfriend, Rosemary Anderson.

The couple argued and Ms Anderson left to walk home. Mr Button followed her to pick her up in his car, but she refused to get in.

After pausing to smoke a cigarette, he drove off to again try to see her safely home — only to find her lying injured and unconscious by the side of the road, having been run down by Cooke. She died from her injuries later that night and Mr Button was subsequently charged with her wilful murder. Although he was to be convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter — thereby saving him from the gallows — Mr Button served five years in Fremantle Prison for a crime he was later found not to have committed.

Wife told to give alibi

Darryl Beamish, a profoundly deaf teenager, was convicted another of Cooke’s murders, the brutal 1959 killing of heiress Jillian Brewer in her Cottesloe apartment, and was also later exonerated. Cooke had confessed to killing both Ms Brewer and Ms Anderson on his arrest, but recanted his confession two days later.

However, he later re-asserted his guilt and was able to give chillingly accurate details of the crime scenes and timelines. Despite this, police continued to refuse to accept his confessions. These stories are told in detail in Wrongful.

Also included is an interview with Cooke’s widow and mother of their seven children, Sally Cooke, who recalls how her husband wanted an alibi.

Sally: “I remember it was about 10 o’clock in the morning and he’d been reading the paper in bed and he called me in and he said, ‘Look at this,’ and I said, ‘Oh, how dreadful, another murder,’ and he said, ‘Yes’.”

“He said, ‘Now you know with the record I’ve got?’ And I said, ‘Yes?’

He said, ‘Well if anyone comes checking up, would you please tell them that I was home early and that we spent the night with relatives?

“‘Because with my record they won’t be fussy and they’ll pin it on me.'”Journalist: “And, in fact, did you later tell this to the police?”

Sally: “Yes, I did.”

Cooke went to trial for the wilful murder of John Sturkey, one of the Australia Day shooting victims, and pleaded not guilty on the grounds of insanity. The jury took only an hour-and-a-half to find him guilty of wilful murder — the singular conviction all that was needed to send him to the gallows.

He was never tried for any of the other murders.

Just 15 minutes before he was executed, Cooke reportedly swore on a bible that he had killed Ms Anderson and Ms Brewer. Wrongful explores the convictions of Mr Button and Mr Beamish and how, despite compelling evidence to the contrary, it took them 39 and 44 years respectively to have their sentences quashed.

Other episodes of the five-part podcast explore the wrongful conviction of Andrew Mallard for the murder of jeweller Pamela Lawrence in Mosman Park, as well as that of the Mickelberg brothers for the 1982 Perth Mint swindle and Gene Gibson for the 2010 murder in Broome of Josh Warneke.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-14/eric-edgar-cooke-serial-killer-voice-heard-53-years-later/9122724?nw=0&r=HtmlFragment