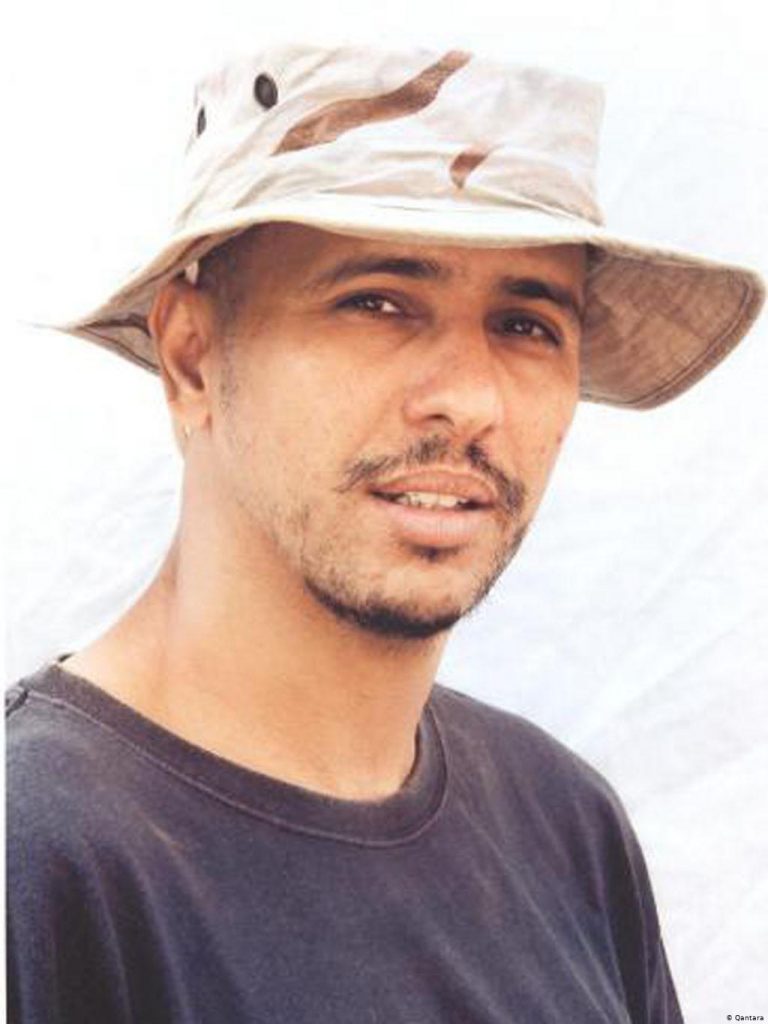

Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Arabic: محمدو ولد الصلاحي) (born December 21, 1970) is a Mauritanian man who was detained at Guantánamo Bay detention camp without charge from 2002 until his release on October 17, 2016.

Slahi wrote a memoir in 2005 while imprisoned, which the U.S. government declassified in 2012 with numerous redactions. The memoir was published as Guantánamo Diary in January 2015 and became an international bestseller. Slahi is the first Guantánamo detainee to publish a memoir while imprisoned. He was prohibited from receiving a copy of his published book while imprisoned.

Slahi wrote four other books whilst in detention, one of which he describes as being “about finding happiness in a hopeless place”, but he has not been allowed to access these books since being removed from Guantanamo.

Slahi was held under the authority of the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), enacted on September 18, 2001. The U.S. government alleged he was part of al Qaeda at the time of his arrest in November 2001.

Slahi traveled from his home in Germany to Afghanistan in December 1990 “to support the mujahideen.” At that time, the mujahideen in Afghanistan were attempting to topple the communist government of Mohammad Najibullah. The United States also supported the mujahideen against Najibullah. Slahi trained in an al Qaeda camp and swore bayat to the organization in March 1991. He returned to Germany soon after, but traveled back to Afghanistan for two months in early 1992. Slahi said that, after leaving Afghanistan the second time, he “severed all ties with … al-Qaeda.” The U.S. government maintains that Slahi “recruited for al-Qaeda and provided it with other support” since then.

Slahi lived in Montreal, Quebec, Canada from November 1999 to January 2000, during which the millennium attack plots were thwarted. Slahi was suspected of involvement in the attempted LAX bombing and was investigated by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. Due to the scrutiny, Slahi returned to live in Mauritania, where he was questioned and cleared of involvement. After the September 11 attacks, the U.S. again was interested in Slahi. He turned himself in to Mauritanian authorities for questioning about the millennium plot on November 20, 2001. He was detained for seven days and questioned by Mauritanian officers and by agents of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

The CIA then transported Slahi to a Jordanian prison through its extraordinary rendition program; he was held for eight months. Slahi said he was tortured by the Jordanians. After being flown to Afghanistan and held for two weeks, he was transferred to military custody and the Guantánamo Bay detention camp in Cuba on August 4, 2002.

Slahi was subjected to sleep deprivation, isolation, temperature extremes, beatings and sexual humiliation at Guantánamo. In one documented incident, he was blindfolded and taken out to sea in a boat for a mock execution. Lt. Col Stuart Couch refused to prosecute Slahi in a Military Commission in 2003. He said that “Slahi’s incriminating statements—the core of the government’s case—had been taken through torture, rendering them inadmissible under U.S. and international law.”

In 2010, Judge James Robertson granted a writ of habeas corpus, ordering Slahi to be released on March 22. In his unclassified opinion, Judge Robertson wrote: “… associations alone are not enough, of course, to make detention lawful.” The Department of Justice appealed the decision. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the ruling and remanded the case to the District Court on November 5, 2010, for further factual findings. The District Court never held the second habeas hearing.

On July 14, 2016, Slahi was approved by a Periodic Review Board for release from detention. Slahi was freed and returned to Mauritania on October 17, 2016; he was imprisoned at Guantánamo for over fourteen years.

1988–1999

Slahi was an exceptional student in high school in Mauritania. In 1988, he received a scholarship from the Carl Duisberg Society to study in West Germany, where he earned an electrical engineering degree from the University of Duisburg. In 1991, Slahi travelled to Afghanistan to join the Mujahideen fighting against the communist central government. The United States had supported the Mujahideen against the Soviet occupation starting in 1979, and funnelled billions of dollars of weapons and aid to the “freedom fighters”. After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, there was a civil war between Mohammad Najibullah‘s government and the Mujahideen. Slahi trained for several weeks at the al Farouq training camp near Khost, which was run by al Qaeda, one of many Mujahideen groups in the civil war. At the end of his training in March 1991, he swore bayat to al Qaeda and was given the kunya (nom de guerre) of “Abu Musab.” However, he did not participate in the civil war, instead returning to Germany.

In February 1992, Slahi travelled again to Afghanistan and was assigned to a mortar battery in Gardez. Six weeks later, the Najibullah regime fell and he returned to Germany. In hearings in Guantanamo, Slahi has stated that he travelled to Afghanistan twice, attended the al Farouq training camp, and fought against the Afghan central government in 1992, but that he was never an enemy combatant against the United States. In fact, he was fighting on the same side as the United States, which in 1992 supported the Mujahideen fight against the communist government in Afghanistan.

Slahi’s cousin and former brother-in-law is Mahfouz Ould al-Walid, also known as Abu Hafs al-Mauritania. Before the September 11 attacks in the United States, Al-Walid was a spiritual adviser to Osama bin Laden, was on the Shura council of al Qaeda, and headed the sharia council. However, two months before the attacks, al-Walid, along with several other al Qaeda members, wrote a letter to bin Laden opposing the planned attacks. Al-Walid left al Qaeda after the attacks.

While al-Walid was in Sudan, where al Qaeda was based in the mid-1990s, he twice asked Slahi to help him get money to his family in Mauritania, about $4,000 in December 1997 and another $4,000 in December 1998. In the 2010 habeas corpus opinion for Slahi, the judge wrote: “the government relies on nothing but Slahi’s uncorroborated, coerced statements to conclude that the money transfers were done on behalf of and in support of al-Qa’ida.” In 1998, Slahi was heard by U.S. intelligence talking to al-Walid on a satellite phone traced to bin Laden.

The 9/11 Commission Report, based on the interrogations of Ramzi bin al-Shibh, claimed that in 1999, Slahi advised three members of the Hamburg Cell to travel to Afghanistan to obtain training before waging jihad in Chechnya. However, the federal District Court in 2010 that reviewed Slahi’s case found that Slahi “provided lodging for three men for one night at his home in Germany [in November 1999], that one of them was Ramzi bin al-Shibh and that there was discussion of jihad and Afghanistan.”

1999–2002

Slahi moved to Montreal, Quebec, Canada in November 1999 because German immigration authorities would not extend his visa for residence in Germany. Since he was a hafiz, he was invited by the imam of a large mosque to lead Ramadan prayers. Ahmed Ressam, who was caught with explosives crossing the Canada–US border in December 1999 as part of the 2000 millennium attack plot, had attended the same mosque. Since Slahi was known to U.S. intelligence through contact with his cousin Mahfouz Ould al-Walid, he was suspected by them of activating Ressam.

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) put Slahi under surveillance for several weeks but did not find any grounds to arrest him. According to a classified report of German intelligence, “there is not only no evidence of any involvement by Ould Slahi in the planning and preparation of the attacks, but also no indication that Ressam and Slahi knew each other.” Slahi left Canada on January 21, 2000, to return to Mauritania.

During his trip home, Slahi was arrested in Senegal at the request of United States authorities and questioned about the millennium plot. He was transferred to Mauritania to be interrogated by local authorities and United States FBI agents. After three weeks in custody, during which Slahi was accused of being involved in the millennium plot, he was released.

Slahi worked at various companies in Mauritania as an electrical engineer starting in May 2000. After the September 11 attacks, the U.S. renewed scrutiny of everyone suspected of having ties to al Qaeda. On September 29, he was again detained by the Mauritanian authorities for questioning. He cooperated with the authorities several more times and then for the last time starting on November 20, 2001. Slahi was interrogated by both Mauritanian officials and the FBI for seven days.

Then the CIA transported him to Jordan using extraordinary rendition. The CIA supervised his interrogation at a Jordanian prison for eight months.[9][34] Slahi claims he was tortured and forced to confess to involvement with the millennium plot. On July 19, 2002, the CIA transported Slahi to Bagram, Afghanistan, where he was transferred to military custody and held at the detention facility. The US military flew Slahi to Guantanamo Bay detention camp on August 4, 2002.[9]

Guantánamo Bay detention

Slahi was assigned detainee ID number 760 and was initially held in Camp Delta. Officials belonging to the CSIS interviewed Slahi in February 2003. He was among 14 men classified as high-value detainees, for whom United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld authorized use of what were called extended interrogation methods, which have since been classified as torture. By January 2003, US military interrogators pressed to make Slahi their second “Special Project,” drawing up an interrogation plan like that used against Mohammed al-Qahtani. Declassified documents show that Slahi was transferred to an isolation cell near the end of May and abusive interrogation started. He was subjected to extreme cold and noise, extended sleeplessness, forced standing or other postures for extended periods of time, threats against his family, sexual humiliation and other abuses.

In February 2015, a series in The Guardian reported that one of his interrogators was Richard Zuley, a career homicide detective with the Chicago Police Department, who was called in on assignment with the United States Navy Reserve. In Chicago, Zuley has been the subject of civil suits by inmates attributing similar abuse, including shackling, threats and coerced confessions.

In September 2003, Slahi was moved to Camp Echo.[22] Memos summarizing meetings held on October 9, 2003 and February 2, 2004 between General Geoffrey Miller and Vincent Cassard of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) acknowledged that camp authorities were not permitting the ICRC to have access to Slahi, due to “military necessity.”

Lt. Col V. Stuart Couch, a Marine Corps lawyer, was appointed as Slahi’s prosecutor at Guantanamo. He withdrew from the case in May 2004 after reviewing it in depth. Couch said that he believed that Slahi “had blood on his hands,” but he “could no longer continue the case in good conscience” because of the alleged torture, which tainted all confessions Slahi had made. Couch said that “the evidence is not believable because of the methods used to obtain it and the fact that it has not been independently corroborated.”

The Wall Street Journal published a letter that Slahi wrote to his lawyers on November 9, 2006. In the letter, Slahi said all his confessions of crimes were the result of torture. He laughed at being asked to recount “everything” that he had said during interrogations, joking that it was “like asking Charlie Sheen how many women he dated.”

According to Peter Finn of the Washington Post in 2010, Slahi, along with Tariq al-Sawah, were “two of the most significant informants ever to be held at Guantanamo. Today, they are housed in a little fenced-in compound at the military prison, where they live a life of relative privilege – gardening, writing and painting – separated from other detainees in a cocoon designed to reward and protect.”

Slahi started writing a memoir of his experiences in 2005, continuing into the next year. The more than 400-page manuscript was declassified by government censors in 2012 after numerous redactions. Excerpts were serialized in Slate magazine beginning in April 2013. It was published as a book, Guantánamo Diary, in January 2015.

Joint Review Task Force

When he assumed office in January 2009, President Barack Obama repeated his commitment to close Guantanamo. He convened a six-agency task force to review the detainees and recommend those who could be released. In its 2010 report, the Guantánamo Review Task Force recommended Slahi be considered for prosecution in a military commission.The task force recommended that detainees deemed too dangerous to release, but without sufficient evidence for prosecution, receive a Periodic Review Board hearing. In 2013, Slahi was listed as one of 71 detainees eligible for a review.[47] In March 2016, Slahi was granted a hearing before the Board in June.

Further interrogation request

US District Court Judge James Robertson had issued an order to the Department of Defense barring them from interrogating Slahi while his habeas corpus case was under consideration. Guantánamo authorities in October 2014 seized all of Slahi’s privileged legal papers and all his personal belongings, including a computer. They also stripped Slahi of his “comfort items,” including letters from his late mother, in an attempt to force him to agree to interrogations. Slahi wrote in an unclassified letter to his attorneys in April 2015 that officials had offered to return these items if he agreed to interrogations, which had been barred for six years. Prosecutors in the case of Ahmed al-Darbi wanted to interrogate Slahi about him.

Torture

Slahi was last interrogated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on May 22, 2003. His FBI interrogator warned him “this was our last session; he told me that I was not going to enjoy the time to come.” Three months later Defense Secretary Rumsfeld approved the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which are well known as torture. Slahi was subjected to isolation, temperature extremes, beatings and sexual humiliation by military interrogators. In one incident, he was blindfolded and taken out to sea for a mock execution.

Schmidt-Furlow Report

A 2007 Wall Street Journal report paraphrased an incident described in the 2005 Schmidt-Furlow Report, an investigation by the Department of Defense into detainee treatment at Guantanamo following FBI allegations of torture used by DOD interrogators in the early years of Guantanamo:

On July 17, 2003, a masked interrogator told Mr. Slahi he had dreamed of watching detainees dig a grave…. The interrogator said he saw “a plain, pine casket with [Mr. Slahi’s] identification number painted in orange lowered into the ground.”

In the summer of 2003, Slahi was repeatedly subjected to the use of an interrogation technique which the Schmidt-Furlow Report stated had been prohibited by the Secretary of Defense on December 2, 2002.

What was not revealed until 2008 was that in a March 14, 2003, legal opinion memo issued by John Yoo of the Office of Legal Counsel, Department of Justice, to the General Counsel of the Department of Defense, Yoo advised that federal laws related to torture and other abuses did not apply to interrogations overseas. At that point the Bush administration contended that Guantanamo Bay was outside US jurisdiction. The Defense Department used this memo to authorize the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” at Guantanamo and in Iraq. Also, by 2005, the New York Times reported that by an April 2003 memo from Rumsfeld to General James T. Hill, commander of United States Southern Command, responsible for Guantanamo Bay, Rumsfeld authorized 24 specific permitted interrogation techniques to be used. Jack Goldsmith, head of the Office of Legal Counsel, withdrew the Yoo Torture Memos in June 2004 and advised federal agencies not to rely on them.

Slahi’s lawyers in 2008 threatened to sue Mauritanian, Jordanian and US officials over his torture.

Senate Armed Services Committee Report

The United States Senate Committee on Armed Services produced a report titled Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in U.S. Custody on November 20, 2008. It contains information about the treatment of Slahi and others at Guantanamo before 2005.

Habeas corpus proceedings

In Rasul v. Bush (2004), the United States Supreme Court ruled that detainees at Guantánamo Bay detention camp had the right of habeas corpus to challenge their detention. Slahi had habeas petitions submitted on his behalf. In response, the Department of Defense published 27 pages of unclassified documents from his Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) on July 14, 2005.

The Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA) mandated that Guantánamo detainees were no longer entitled access to the U.S. federal courts, so all pending habeas petitions were stayed. However, in June 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in Boumediene v. Bush that the MCA of 2006 could not remove detainees’ right to habeas and access to the federal court system. All previous habeas petitions were eligible to be re-instated.

Before submitting briefs in the habeas case, the U.S. government dropped its previous allegations that Slahi had participated in the Millennium Plot and that he knew about the 9/11 attacks before they happened.

Release order

After review of the case, US District Court Judge James Robertson granted the writ of habeas corpus and ordered Slahi’s release on March 22, 2010. Robertson’s ruling was criticized by several Republican Party politicians. Slahi was the 34th detainee whose release was ordered by a federal district court judge reviewing government materials associated with his habeas petition. The unclassified decision was filed on April 9, 2010.

Referring to the government’s charge that Slahi gave “purposeful and material support” to al Qaeda, Judge Robertson wrote:

Salahi may very well have been an al-Qaida sympathizer, and the evidence does show that he provided some support to al-Qaida, or to people he knew to be al-Qaida. Such support was sporadic, however, and, at the time of his capture, non-existent. In any event, what the standard approved in Al-Bihani actually covers is “those who purposefully and materially supported such forces in hostilities against U.S. Coalition partners.” 530 F.3d at 872 (emphasis added). The evidence in this record cannot possibly be stretched far enough to fit that test.:5

Judge Robertson addressed the other government allegation, that Slahi was “part of” al Qaeda at the time of his capture. He said the law was not as clear in this instance:

neither Al-Bihani nor any other case provides a bright-line test for determining who was and who was not “part of” al-Qaida at the time of capture. The decision, in other words, depends on the sufficiency of the evidence. The question of when a detainee must have been a “part of” al-Qaida to be detainable is at the center of this case, because it is clear that Salahi was at one point a sworn al-Qaida member.:

Judge Robertson discusses other factors in his decision, including which side had the burden of proof and considering the reliability of coerced or hearsay testimony. In conclusion, Judge Robertson stated:

The government had to adduce evidence – which is different from intelligence – showing that it was more likely than not that Salahi was “part of” al-Qaida. To do so, it had to show that the support Salahi undoubtedly did provide from time to time was provided within al-Qaida’s command structure. The government has not done so.[12]:31

Appeal

The Department of Justice appealed the decision. Oral arguments were heard on September 17, 2010, by a three-judge panel for the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. In oral arguments, Judge David S. Tatel questioned whether swearing bayat in 1991 is evidence of actions a decade and more later against the United States. He noted, “When he swore bayat, the United States and al-Qaeda had a common goal. Both the United States and al-Qaeda were opposing a communist government of Afghanistan.” The panel discussed sending the case back to the District Court or over-ruling the decision, based on other recent D.C. Circuit rulings on the criteria that justify detention, which were still being developed.

On November 5, 2010, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the decision and remanded the case to the D.C. District Court for further factual findings, based on guidance it had given to the D.C. District Court about review of such habeas corpus cases of detainees. The Circuit Court panel said the following questions needed to be answered:

- whether Slahi understood that he was referring recruits to work in al-Qaeda’s “jihad” against the U.S.,

- what Slahi may have said to bin al-Shibh in a discussion of jihad in Afghanistan,

- whether he had been asked by al-Qaeda to help with communications projects in Afghanistan and elsewhere,

- whether he had taken a role in planning computer “cyberattacks,” and

- whether he remained “a trusted member” of al-Qaeda up to the time of his capture.

The District Court never held any hearings after the Court of Appeals decision.

Guantánamo Diary

Main article: Guantanamo Diary (memoir)

In 2005, Slahi wrote a memoir while held in detention. The 466-page manuscript was in English, a language Slahi learned at Guantánamo. After litigation and negotiation, the US government declassified the memoir six years later, making numerous redactions. Excerpts were published by Slate magazine as a three-part series beginning April 30, 2013. On May 1, 2013, Slate also published a related interview with Col. Morris Davis, the military’s chief prosecutor at Guantánamo from September 2005 to October 2007.

The book, Guantánamo Diary, was published in January 2015. It is the first work by a still-imprisoned detainee at Guantánamo. It provides details of Slahi’s harsh interrogations and torture, including being “force-fed seawater, sexually molested, subjected to a mock execution and repeatedly beaten, kicked and smashed across the face, all spiced with threats that his mother will be brought to Guantánamo and gang-raped.” It has become an international bestseller. Prison officials prevented Slahi from receiving a copy of his published book.

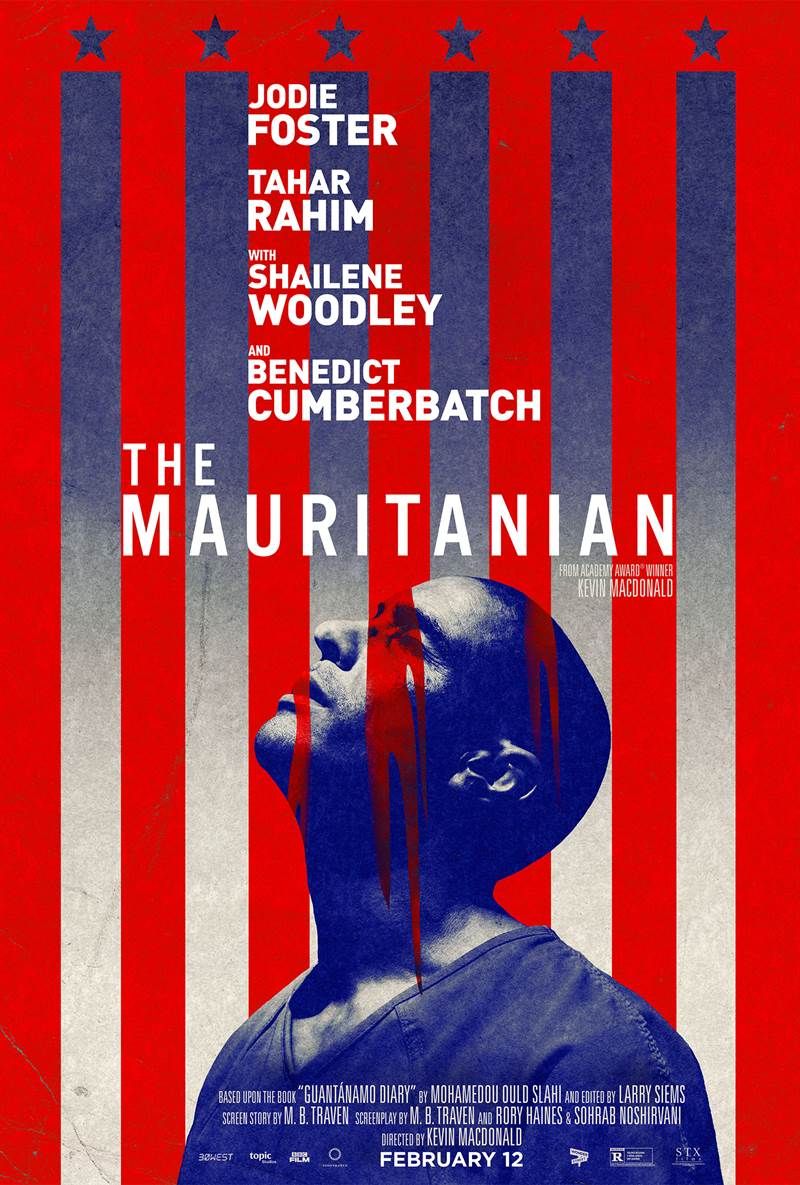

Film adaptation

A film adaption of the memoir titled The Mauritanian directed by Kevin Macdonald, and starring Jodie Foster, Tahar Rahim, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Shailene Woodley was released on February 12, 2021.

Release from Guantánamo Bay

Slahi had his first Periodic Review Board review on June 2, 2016. A month later, the board recommended that Slahi be released. On October 17, 2016, Slahi was freed and returned to Mauritania, after being detained without charge for over 14 years.

CBS interview

CBS News journalist Holly Williams traveled to Mauritania to interview Slahi. CBS News‘ flagship news show, 60 Minutes, broadcast the story on March 12, 2017. CBS News described it as Slahi’s first television interview since his repatriation. In this interview Mohamedou said he “wholeheartedly [forgives] everyone who wronged [him] during [his] detention.”

Reunion with Guantanamo guard

In May 2018, Slahi’s former guard at Guantanamo, Steve Wood, visited him in Mauritania over Ramadan in what long-time Guantanamo reporter Carol Rosenberg described as a ‘remarkable reunion’.[

Travel restriction

Slahi’s passport has not been returned to him as was promised during his release. He is not able to leave Mauritania to treat his health condition or see his newborn son in Germany.

Open letter to President Biden

On January 29, 2021 the New York Review of Books published an open letter from Slahi, and six other individuals who were formerly held in Guantanamo, to newly inaugurated President Biden, appealing to him to close the detention camp.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohamedou_Ould_Slahi

صاحب أكثر كتاب مبيعا في الولايات المتحده الاميركيه

محمدو ولد الصلاحي (وُلِد في 31 كانون الأول ديسمبر، 1970) هو مهندس اتّصالات موريتاني سُجِن في قاعدة غوانتنامو العسكرية من سنة 2002 إلى أن أُفرِج عنه في أكتوبر 2016. اعتقلت الحكومة الأمريكية محمدّو (يُنطَق الاسم بتشديد حرف الدال) بموجب الإذن باستخدام القوة العسكرية ضد الإرهابيين، متهمة إياه بالانتساب لتنظيم القاعدة وقتَ اعتقاله في نوفمبر 2001. اعتقلت السلطات الموريتانية محمدّو في نوفمبر 2001 ثم سلّمته بعد التحقيق معه إلى الأردن الذي نُقل منه بعد ثمانية أشهر من التحقيق إلى قاعدة باغرام العسكرية في أفغانستان ومنها إلى معتقل غوانتانامو. لم يعلم ذوو محمدّو ولد الصّلاحي بنقله من موريتانيا إلا بعد أشهر، عندما قرأ أخوه المقيم في ألمانيا خبرا في صحيفة شبيغل الألمانية عن نقله إلى غوانتنامو.

حياته

درس محمدّو ولد الصّلاحي هندسة الاتصالات في ألمانيا، وسافر إلى أفغانستان سنة 1990 للمشاركة في الحرب ضدّ الروس إلا أنه عاد بعد ذلك إلى ألمانيا وأكمل دراسته هناك. ادّعت الحكومة الأمريكية أن محمدّو كان ينتمي وقتَ اعتقاله إلى تنظيم القاعدة؛ إلا أنه نفى ذلك مؤكدا أنه قطع جميع صلاته بالتنظيم بعد آخر رحلاته إلى أفغانستان، والتي دامت شهرين.

استمعت اللجنة الخاصّة بمراجعة ملفات معتقلي غوانتانامو لمحمدو في 2 يونيو/ حزيران 2016 وأوصت في 16 يوليو/ تمّوز بإطلاق سراحه بعد 14 سنة من الاعتقال دون توجيه تهم له. بعد التوصية بالإفراج، طالبت جمعيات حقوقية موريتانيّة سلطات بلدهابمضاعفة الجهود للتسريع بإجراءات تسلّم ولد صلاحي؛ حتى لا يظل في المعتقل لمدّة طويلة، كما هي حال معتقلين آخرين أوصت اللجنة بإطلاق سراحهم منذ مدّة وما زالوا في المعتقل.

اعتمدت السلطات الأمريكية التوصيّة بالإطلاق وأفرجت عن محمدّو في السابع عشر من تشرين الأول / أكتوبر 2016 حيثُ وصل إلى العاصمة الموريتانيّة نواكشوط في نفس اليوم.

يوميّات غوانتنامو

اشتهرت قضيّة محمدّو ولد الصّلاحي بعد نشره، بمساعدة محاميه، كتابا بعنوان “يوميات غوانتانامو”. تصدّر الكتاب قائمة الكتب الأكثر مبيعا في الولايات المتحّدة بعد صدوره. يروي الكتاب، الذي طمست السلطات الأمنية الكثير من كلماته قبل السماح بنشره، قصّة اعتقال محمدّو والتعذيب الذي تعرّض له وحياته في المعتقل.

في 19 فبراير 2021 عُرِض الفيلم الأمريكي الموريتاني، والذي أُخذ عن مذكرات محمدو ولد صلاحي، وجسّد دوره الممثل الفرنسي طاهر رحيم.

Interview with Mohamedou Ould Slahi

“The rule of law means nothing to a corrupt regime”

Mauritanian Mohamedou Ould Slahi spent more than fourteen years in Guantanamo. His “Guantanamo diary”, which has been translated into numerous languages, won him global acclaim. After a protracted legal battle, Slahi finally released in October 2016. In an exclusive interview with Emran Feroz, he talks about his experiences during his imprisonment

How did you feel when you heard that after more than fourteen years in Guantanamo your imprisonment was coming to an end and you would be released?

Mohamedou Ould Slahi: The day I found out, I was sitting in my dark cell as a female US military official came in. She looked at me kindly and asked me: “Did you know you’re going home?” I stared at her mouth and could not believe her. Although the exchange was over in a matter of moments, it took me ages to digest this message. It was just completely surreal. Even now, as I talk to you, I still can′t believe that I am finally free.

Had you given up hope ever coming out?

Slahi: After all the torture, when I finally signed the false confession, which had been repeatedly presented to me, I believed it was final. I was sure that I would never leave Guantanamo again. But at the same time, I had also made peace with myself. I had never killed a single person in my entire life. I knew that. I did not care what the Americans thought of me. Also, once I had signed the confession, my fears for my family went away. My tormentors had often threatened to lock my mother up in Guantanamo as well. For me that was worse than all the torture.

What was your worst experience during your time in Guantanamo?

Slahi: My family is very poor. It was my duty to feed them after my studies and take care of them. I wanted to build a house for my mother. In the end, I was unable to do anything for my family. All my dreams were destroyed. That was soul-destroying. They took away the best years of my life. My mother died while I was in prison. I never got the chance to say good-bye to her.

During your detention, you were repeatedly tortured. Did the information you revealed prove helpful to your tormentors in the end?

Slahi: There were two phases during my “hearings”. At the beginning, I repeatedly insisted that I had not committed a crime and was not a terrorist. I said that I was just a Muslim. But after the torture that changed. I confessed to everything. I agreed that I was a terrorist, just like all the other people I was supposed to be connected with. The authorities analysed my statements, including a lie detection test and quickly realised that my confession was false, together with all my other statements. I wrote about this in my book. But the US government censored this section before the manuscript was released.

Synonymous with torture, caprice and triumphal justice: Republican President George W. Bush had the Guantanamo prison camp erected following the terror attacks on 11 September 2001 with the aim of holding Islamist terrorists without trial. Eight years ago, shortly after his inauguration, Obama signed a decree stipulating the closure of the centre located on the U.S. base on Cuba. Not only did he encounter strong resistance from the Republicans, many in his own party also failed to support him

The one thing the authorities were able to prove is that you were in Afghanistan in the 1990s. Why were you there?

Slahi: In the 1980s and 1990s, it was trendy to go to Afghanistan. The images of Russian soldiers killing innocent Afghans were omnipresent. I too saw these pictures and they got me really worked up. All of a sudden I wanted to go to Afghanistan to fight against the Russian occupation. I was told at the time that there would be a responsible information office in Bonn. At the time, it was the unofficial embassy for the Afghan mujahideen. I visited the office and was issued with a letter of recommendation for the fight. This letter entitled me to a Pakistani visa. I travelled to Khost in the east of Afghanistan via Pakistan. I was trained at Camp Al-Farouq. Looking back, I was totally unaware of what was going on. After my training, I returned to Mauritania. My mother feared for my life. Later, I went back to Afghanistan, to Gardez, in the province of Paktia. Soon afterwards, the mujahideen became corrupt. Once the Russians had left Afghanistan, they fought each other and began destroying their own country. I decided there and then never to return to Afghanistan.

Do you think that the Americans have ultimately benefitted from Guantanamo and the “War on Terror”?

Slahi: The so-called Muslim world has certainly lost a lot. This war has been led by crazy, power-hungry people on both sides. The ordinary people – whether they are in Mauritania or elsewhere – do not want to have anything to do with it. They just want to live in peace. A handful have profited from the “War on Terror”. They include weapons producers or private security companies providing services to state military and intelligence services, not to mention the military-industrial complex in general. The al-Qaida extremists and other groups also need the war. Without the war they would have no reason to exist. They need the war, without it they wouldn′t attract any support.

The broken promise: Barack Obama ultimately failed in his attempt to close the controversial detention centre on Cuba. Nevertheless, shortly after Trump′s presidential victory, he did manage to release 15 detainees to their countries of origin and reduce the camp′s population to a mere 45 inmates. Trump, by contrast, not only wants to keep “Gitmo” running, he also aims to send new prisoners there

What role do the governments of affected countries concerned, such as Mauritania, Jordan or Afghanistan with relation to the USA? In your book, you draw neo-colonial comparisons.

Slahi: It is very obvious that the governments of these states are corrupt, they exploit their populations and act on the interests of the Americans. It’s wrong to always point the finger at Washington. A big problem is here – at home. By surrendering me to the USA, the Mauritanian government acted against its own constitution. This action was unlawful and criminal. The other countries you mentioned acted in similar ways. The problem is that there is no rule of law. Our corrupt governments don′t understand what this word means.

During the presidency of Barack Obama, it was always said that he wanted to close Guantanamo. Did you noticed any signs of this happening during your imprisonment?

Slahi: When Obama was elected, we prisoners also heard about this initiative. I was overjoyed when I heard. My euphoria, however, came to an abrupt end. The responsible intelligence officer told me that Guantanamo wouldn′t be closing. The reason: Obama did not have the power to push it through. I personally think Obama really wanted to close Guantanamo. At the time he was serious in his intention. It was only later that he noticed his hands were tied. There were too many lobby groups in Congress, especially on the political right and within the military-industrial complex, both of which were opposed to the closure.

Donald Trump has said that he wants to fill Guantanamo again. Do you think that we will ever see the prison being closed?

Slahi: The president of a country must protect the constitution. What would happen if a candidate for the office of the German Chancellor were to say that he or she wanted to break fundamental laws? The use of torture and illegal detention are clearly prohibited in the United States. The U.S. president must stick to it. All these announcements are absolutely undemocratic and unlawful. We will see if Trump actually puts any of this into practice or not. It is now widely accepted that he is totally unpredictable and fond of contradicting himself. We can only hope that the American people will tame Trump and will not allow the hell of Guantanamo to be filled with innocent people again.

Interview conducted by Emran Feroz

© Qantrara.de 2017

——–

Mohamedou Ould Slahi was born in Mauritania in 1970. He earned a scholarship to study engineering in Germany when he was 18, and lived and worked in Germany and briefly in Canada before returning to Mauritania in 2000. He was detained without charge in Guantanamo Bay in 2002, where he was repeatedly tortured. While in detention, he wrote the 466-page manuscript which was to become Guantanamo Diary, which became an international bestseller. After fourteen years, Slahi was finally released in October 2016.

GUANTÁNAMO DIARY

The international bestseller that set the world on fire, told in full for the first time: Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s unflinching account of his fourteen years of detention without charge in Guantánamo Bay

https://canongate.co.uk/contributors/10140-mohamedou-ould-slahi/