State: Louisiana Convicted: 1985 Exonerated: 2003

Race: Black DNA used in exoneration? No

Reasons for wrongful conviction: Mistaken witness identification – Perjury or false accusation – Prosecutorial misconduct

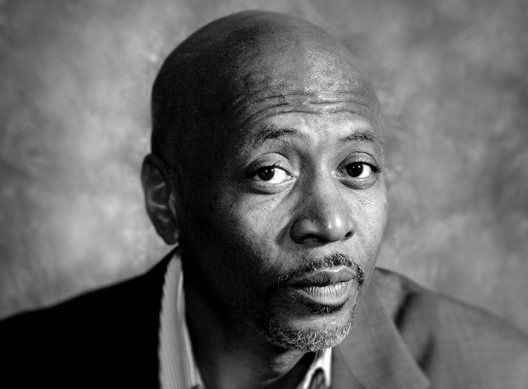

John Thompson spent 18 years in prison for a robbery and murder he did not commit, 14 of them on death row in solitary confinement in the infamous Angola prison in Louisiana. He was exonerated after evidence covered up by New Orleans prosecutors surfaced after his seventh and final execution date was issued for May 20, 1999.

John was arrested in 1985 in New Orleans for the murder of Ray Liuzza, a hotel executive from a prominent family, convicted, and sent to death row at Angola prison. He was arrested based on the false testimony of Kevin Freeman, who had sold the victim’s ring and the gun used in the murder to John, but implicated him the murder. This, coupled with an accusation that John had been involved in an earlier robbery, got him a death sentence. John then retained on appeal pro bono lawyers Michael Banks and Gordon Cooney, from the Philadelphia blue-chip law firm of Morgan Lewis. By 1999, they had exhausted all appeals. Amazingly, an investigator they had hired looked through the evidence one last time found a report sent to the prosecutors 15 years prior and suppressed by them that refuted that John’s blood type matched that of the earlier robbery, as well as the names of witnesses and police reports that cast severe doubt on the prosecution’s case – 10 pieces in all. Thus, the robbery conviction was thrown out, and a retrial was ordered on the murder case. In 2003, a jury took only 35 minutes to acquit John.

John was subsequently awarded a 14 million dollar settlement for prosecutorial misconduct in his case, which was overturned by a divided US Supreme Court decision, Connick v. Thompson, in 2011. Nevertheless, John devoted his time and attention to helping other wrongfully convicted men by establishing Resurrection After Exoneration, a non-profit dedicated to providing reentry services. He also received a prestigious Soros Fellowship to help launch a project to fight prosecutorial impunity in our justice system. JT’s fierce, unyielding voice for justice was an integral part of Witness to Innocence. He successfully challenged us to include advocacy for our members as a part of our mission, equal and complementary to the goal of abolishing the death penalty. In 2017, JT was elected by his fellow exonerees to serve as their representative on the WTI board of directors.

John died on October 3, 2017. That he was taken from us at far too young an age is almost certainly due to the living conditions at Angola and the physical toll of the stress and trauma of being innocent yet coming so close to execution. But his work was far from complete – JT was actively engaged in fighting for justice on so many fronts. His legacy and spirit live on in the continued work to abolish the death penalty in Louisiana and nationally, including a 2018 bill aimed at prosecutorial accountability introduced in Louisiana known as the “John Thompson Prosecutorial Accountability and Professional Standards Bill Prosecutorial Transparency Bill” which, if passed, would establish an oversight commission that would collect data from each district attorney’s office and make the information available to the public. https://www.witnesstoinnocence.org/single-post/john-thompson

John Thompson was many things: death row exoneree, abolitionist, advocate for prosecutorial accountability, spokesperson, founder of an exoneree-run re-entry program, and mentor. Before the news cycle moves on from John, we are compelled to acknowledge the way he most profoundly affected the world.

After his untimely death on October 3rd, the media described him as a man who saw the world as it should be, as angry, and as a warrior. To those of us who enjoyed the enormous privilege of knowing and loving John, he was so much more.

John survives as a symbol of the impunity with which prosecutors may disregard the life and rights of a young black man. Yet he was a wonderfully regular man with a sharp wit and irreverent humor. He loved his wife, family—especially his grandchildren—and friends. He liked a strong coffee in the morning and a beer in the evening. He went to church, and then cursed at the football game. John didn’t sugarcoat anything. He had 100 big ideas a week. He issued straight line challenges—to his colleagues and to the world. Consequently, those who truly knew and loved him maintained a more real, raw and rewarding relationship with John Thompson, compared to others in their lives. He was our friend, and a brilliant, honest, funny, smart, present, and—at times—difficult colleague.

John lived helping and questioning: helping fellow exonerees after release, questioning institutions of criminal justice and challenging them to do better.

But mostly, John Thompson will go down in legal history for demanding the kind of justice a white man would expect––and being told in 2011 he was not entitled to it.

On May 10, 2003, the headline of the Times Picayune read:

Acquitted inmate a free man.

John Thompson, the New Orleans man acquitted this week of a 1984 murder that had once placed him on death row, walked out of the parish prison Friday afternoon after more than 18 years of incarceration.

Every exoneration story is horrifying and fascinating. John’s is extraordinary for many reasons, not least of which was a last-minute defense discovery that saved him from execution and the 35 minutes a jury took to acquit him at his 2003 retrial for the murder he was nearly executed for four years previously. When John walked out of prison, his story could have ended like a movie: a happy and satisfying ending after a tough legal battle, dramatic twists, his swift acquittal, release and subsequent marriage to his wife of now-14 years. But John knew people should not console themselves with a happy ending.

John could have done anything he wanted after 18 years of wrongful imprisonment. He chose to become a selfless, tireless advocate, social worker and mentor for other returning prisoners, establishing the first exoneree-run reentry program in the country. He was working there the day he died, sustaining a network of support among the formerly incarcerated, reconnecting them to the community, and providing education and counseling. He helped dozens.

All the while, he traveled the country questioning the status quo of criminal justice, trying to prevent injustices like his. Although it was prosecutors who nearly had him killed, to his great credit, he did not exclusively focus his criticism there. Police, courts and public defenders also failed John and he understood that the failing of those institutions too affected the lives of the poor and people of color ― particularly black people. John increasingly chose to use his story as a galvanizing cry for racial justice in America. Until his death, John remained a strong advocate for organizations fighting to bring equal justice to an unjust system. He advocated for more judicial oversight, robust public defense and for the urgent work of freeing innocent prisoners.

Famously, John sued the prosecutors who nearly killed him, arguing that prosecutors’ offices need standards to prevent the kind of terrible injustice he suffered. He believed he deserved compensation because the New Orleans District Attorney did not care to have such standards, and consequently, John was ripped from his 6 and 4-year old sons, thrown into solitary confinement for 14 years to await his execution for a murder he did not commit. John survived 7 execution dates (including the last ― set for the day before his youngest son’s high school graduation) and lost 18 years of his life. John wanted the prosecutors to help him rebuild his life and sanity. He asked for the justice any of us would expect if we survived such torture.

A New Orleans judge and jury agreed John’s life mattered, and the prosecutor’s office should pay. But we all know the ending. In 2011 in Connick v. Thompson, five justices of the Supreme Court took John’s victory and validation away, saying the law is not the way to hold prosecutors accountable and, if district attorneys do not train their staff to avoid such injustices, they are not liable. Those four white men and Clarence Thomas were mistaken and morally wrong. To John, and many others, the Supreme Court said his black life did not matter enough for the white prosecutors who nearly killed him to be accountable.

To date, not a single prosecutor from John Thompson’s case has faced a single consequence.”

He later wrote in the New York Times he didn’t care about the money, he just wanted to know why no prosecutor was disbarred or jailed. Swift consequences befell prosecutors who committed misconduct in recent high-profile cases of white defendants. Ted Stevens, the Duke Lacrosse players, Michael Morton: none were nearly killed from prosecutorial misconduct, yet in each case when it was revealed, the outrage was palpable and the penalty swift. To date, not a single prosecutor from John Thompson’s case has faced a single consequence. So he filed a complaint with the Justice Department last year, asking for a civil rights investigation into those prosecutors. But John Collin Thompson died with little faith that Jefferson Beauregard Sessions’ Justice Department was actively concerned with his complaint.

Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, identifies the U.S. as unique in the world for the rate at which its prisoners so disproportionately correlate with its racial minority: African Americans. Recently her work, and that of other criminal justice reform advocates, has increased popular understanding that the struggle for a smaller, fairer, more accurate and more accountable criminal justice system is a seamless part of the struggle for civil rights and racial justice in America. John’s life-defining struggle to hold prosecutors to account was firmly part of that struggle.

On June 7, 1892, three miles from where John Thompson was convicted and later acquitted, Homer Plessy sat in a rail carriage reserved for white people and was charged with violating the Louisiana law forbidding people of color and white people from sitting in the same carriage. When Homer Plessy took his case to the Supreme Court, in another sorry decision, it said, “If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” It said that he had been “assigned by officers of the company to the coach used for the race to which he belonged, but he insisted upon going into a coach used by the race to which he did not belong.”

So, too, John Thompson was assigned to be grateful with his acquittal and move on. When the U.S. Supreme Court took away the jury’s verdict that had acknowledged the irreparable but avoidable damage to his life, it effectively said: “John Thompson is insisting upon the kind of justice used by the race to which he does not belong.”

Today, Plessy v. Fergusson is a relic from a morally misguided time. Here in New Orleans, the descendants of Homer Plessy and Judge Howard Ferguson ― Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson ― established the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation to teach justice and equity and “connect communities to history in an effort to bring a greater understanding, respect, and vision for who we are today and who we can be tomorrow.” They presented John’s lawyers with an award at a dinner in New Orleans in 2013.

When the Supreme Court overturned Plessy in 1955 with Brown v. Board of Education, it prescribed that “separate” is inherently unequal. That decision was part of a long social and political struggle for true equality that continues today in criminal courts across America. To John, the Connick decision said that his black life didn’t matter and that, while we may not be formally separate, we are still absolutely unequal. This energized thousands of people who knew and loved John, and thousands who did not, to work harder for true equality. Ironically, this gives John far more power and consequence in history than the prosecutors who were at best indifferent to his guilt while they tried to kill him in the name of their sorry careers.

In 1898, Homer Plessy was right and the Supreme Court was wrong. 123 years later, John Thompson was right and the Supreme Court was wrong. We look forward to the day that Connick is considered a relic from a morally misguided time.

There again is the power of John Thompson’s story, showing us who we really are.”

Some of us who have had the monumental privilege of knowing John take a perverse satisfaction in seeing last week that the man who argued to reverse his jury verdict in the Supreme Court was nominated to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Because if John’s legacy speeds all of America’s realization that its society ― as reflected in its courts ― does not value black lives as it does white lives, he will continue to rest in the incredible power he had in life. John died early of a heart attack that was undoubtedly caused by the stress of what he had endured at the hands of the State of Louisiana. Days before, Kyle Duncan, the man who had argued that the prosecutors need not be liable for the terrible damage they caused him and his community, was elevated to one of the highest positions in the law. There again is the power of John Thompson’s story, showing us who we really are.

John spent his life asking us all hard questions. He asked the hardest question of the highest court in the country: does my life matter enough? He showed the country the answer, and left us to do something about it. We just wish he was still here to do it with us.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-legacy-of-john-collin-thompson-proves-the-flaws-in-our-court-system_b_59e4d914e4b0a52aca19a416