Mieczysław Weinberg werd in Polen geboren. Hij was Joods. Door zijn omzwervingen en de behandeling van het ‘Joodse vraagstuk’ in Rusland werd hij ook bekend onder de namen Wainberg, Vaynberg, etc. Ook op sommige cd-uitgaves staan andere spellingen van zijn naam vermeld. Zijn voornaam wordt ook wel als Moishei, Moisey of Moses gebracht; dat is ook incorrect.

De verwarring is waarschijnlijk in 1939 ontstaan toen hij naar Rusland vluchtte en een douaneambtenaar de namen van de familieleden bewust verkeerd in de douanedocumenten veranderde om de Joodse associaties eruit te halen.

Leven

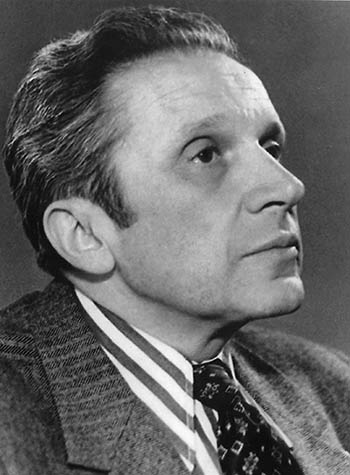

Zijn familie kwam oorspronkelijk uit Bessarabië. Daar werden familieleden tijdens de Kishinyov-pogrom in 1903 vermoord. Zij emigreerden daarna naar Warschau, waar zijn vader als musicus verbonden raakte aan het Joodse theater. Hij studeerde piano bij Józef Turczyński aan het conservatorium van Warschau. Al gauw werden zijn muzikale talenten ontdekt, onder andere door Józef Hofmann, en geprezen.

Tijdens de Duitse invasie in Polen in 1939 vluchtte hij naar Rusland. Zijn ouders en zuster bleven in Polen waar zij uiteindelijk werden vermoord. In Minsk studeerde hij onder Vasily Zolotaryov die een voormalige student van Nikolaj Rimski-Korsakov en Mili Balakirev was.

De ochtend na Weinbergs diploma-uitreiking vielen de Duitsers Rusland binnen en vluchtte hij naar Tasjkent. Daar werkte hij bij de opera en ontmoette allerlei belangrijke personen die ook geëvacueerd waren. Onder hen was ook de beroemde directeur van Het Joods Theater in Moskou, Solomon Mikhoels. Hij trouwde met diens dochter.

Onder de indruk van Weinbergs eerste symfonie regelde Dmitri Sjostakovitsj in 1943 dat Weinberg naar Moskou kon komen. Daar bleef hij tot het einde van zijn leven.

Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog laaide het antisemitisme in Rusland op. In januari 1948 werd zijn schoonvader door de geheime politie vermoord en vele Joden met een culturele achtergrond werden gearresteerd en later doodgeschoten. Weinberg bleef buiten schot, maar in 1953 werd hij gearresteerd met de aanklacht dat hij een Joodse republiek in de Krim op zou willen richten. Sjostakovitsj nam het voor Weinberg op in een brief aan Stalins rechterhand Beria, maar waarschijnlijk ontsnapte Weinberg vooral aan de dood doordat Jozef Stalin op 5 maart 1953 overleed, waarna de autoriteiten geen tijd meer hadden zich in zijn, en veel andere, zaken te verdiepen.

Werk

Hij componeerde 26 symfonieën en 17 strijkkwartetten en vele andere werken. Het grootste gedeelte van zijn werk werd in Rusland door de beroemdste en bekendste musici en orkesten uitgevoerd, onder andere door David Oistrakh, Emil Gilels, Rudolf Barshai en Mstislav Rostropovitsj.

De componist Aram Khachaturian stelde dat Weinberg een van de vier componisten was die Dmitri Sjostakovitsj hoog in het vaandel had staan: Nina Makarova, Tikhon Khrennikov, Boris Tsjaikovski en Weinberg. (Dat Sjostakovitsj Khrennikov genoemd zou hebben is verbazend omdat hij een van de saaiste en meest formele Russische componisten is geweest. Waarschijnlijk hadden Sjostakovitsj en Khachaturian hier politiek sarcastische bedoelingen mee).

Tussen Weinberg en Dmitri Sjostakovitsj werd het gewoonte om elkaar hun werken te laten zien voordat ze werden uitgevoerd en gepubliceerd. Sjostakovitsj liet het nooit zover komen dat muzikale suggesties van anderen hem een werk deden aanpassen. Hierop was één uitzondering: Weinbergs opmerkingen bij het vierde strijkkwartet in 1949.

Overeenkomsten tussen de werken van Weinberg en Sjostakovitsj zijn talrijk. Het begin van Weinbergs vierde en vijfde symfonie zou ook door Sjostakovitsj gecomponeerd kunnen zijn. Delen uit Dmitri Sjostakovitsj twaalfde en dertiende symfonie klinken weer in Weinbergs werk.

Weinberg was bijzonder gesteld op de creatieve mogelijkheden van het strijkorkest. Hij stelde ‘ik heb vaak niet meer nodig dan een goed strijkorkest om mijn gevoelens in muziek tot uiting te brengen’. Voorbeelden zijn de tweede en tiende symfonie en de kamersymfonieën. Zijn werken werden door de Sovjetautoriteiten regelmatig geprezen, vooral in het naoorlogse klimaat. Toch kon een Joodse componist nooit zeker van zijn zaak zijn. De officiële ontvangst van zijn werk was wisselend en heel inconsistent.

Daar waar Dmitri Sjostakovitsj een onaantastbare grootheid was geworden gold dat zeker niet voor Weinberg (en vele anderen). Vaak dreigde arrestatie en net als Sjostakovitsj had Weinberg altijd een koffertje klaarstaan om bij een eventuele arrestatie nog iets te kunnen meenemen. In 1948 werd de eerste Sinfonietta openlijk door de autoriteiten geprezen terwijl dit werk toch duidelijke verwijzingen naar Joodse muziek in zich heeft. Andere werken werden weer op de, nooit gepubliceerde en inofficiële, zwarte lijst gezet. Dit was de beruchte ‘Prikaz no. 17’.

Vele malen nam Weinberg, net als Sjostakovitsj, een loopje met de muziekkennis van de autoriteiten. Zijn Rapsodie op Moldavische thema’s op.47, no.1 wemelt dermate van Joodse associaties dat het onbegrijpelijk is dat dit werk officieel werd geprezen. Een andere versie van dit werk voor viool en orkest werd door David Oistrakh in 1953 in première gebracht en dezelfde avond werd Weinberg gearresteerd.

Opnames

In het Westen was Weinberg tot voor kort alleen bij kenners bekend maar stilaan groeit het aantal bewonderaars. Dit is mede te danken aan het cd-label OLYMPIA, dat veel van zijn werken in originele uitvoering uitbracht, en aan musicologen zoals Per Skans. Ondertussen wordt meer en meer werk van Weinberg beschikbaar voor de hartstochtelijke muziekliefhebber. Het Engelse label Chandos is in 2004 gestart met een registratie van alle symfonieën van Weinberg met het Pools Nationaal Radio-orkest, Katowice onder leiding van Gabriel Chmura. Het Quatuor Danel heeft alle strijkkwartetten opgenomen voor het label CPO. Ook van de altvioolsonates (Julia Rebekka Adler voor het label Neos), de vioolsonates en de cellosonates zijn uitvoeringen verkrijgbaar.

Weinberg 8 December 1919 – 26 February 1996) was a Polish-born Soviet composer. Ever since a revival concert series in the 2010 Bregenz Festival in Austria, his music has been increasingly described as “some of the most individual and compelling music of the twentieth century”. Weinberg’s output was extensive, encompassing 26 symphonies, 17 string quartets, nearly 30 sonatas for various instruments, 7 operas, and numerous film scores.

Names

Much confusion has been caused by different renditions of the composer’s names. In official Polish documents (i.e. prior to his move to the USSR), his name was spelled as Mojsze Wajnberg, and in the world of Yiddish theater of antebellum Warsaw he was likewise known as Yiddish: משה װײַנבערג (Moishe Weinberg). In the Russian language (i.e. after his move to the Soviet Union), he was and still is known as Russian: Моисей Самуилович Вайнберг (Moisey Samuilovich Vaynberg), which is the Russian-language analogue of the Polish original Mojsze, son of Samuel. Among close friends in Russia, he would also go by his Polish diminutive Mietek (i.e. Mieczysław).

Re-transliteration of his surname from Cyrillic (Вайнберг) back into the Latin alphabet produced a variety of spellings, including ‘Weinberg’, ‘Vainberg’, and ‘Vaynberg’. The form ‘Weinberg’ is now being increasingly used as the most frequent English-language rendition of this common Jewish surname, notably in the latest edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and by Weinberg’s first biographer, Per Skans.

Life

Early life in Poland, Belarus and Uzbekistan

Weinberg was born on 8 December 1919 to a Jewish family in Warsaw. His father, Shmil (Szmuel or Samuil Moiseyevich) Weinberg (1882–1943, Russian), a well-known conductor and composer of the Yiddish theater, moved to Warsaw from Kishinev (at that time a part of the Russian Empire) in 1916 and worked as a violinist and conductor for the Yiddish theatre Scala in Warsaw, where the future composer joined him as pianist at the age of 10 and later as a musical director of several performances. His mother, Sonia Wajnberg (née Sura-Dwojra Sztern, 1888–1943), born in Odessa (at that time a part of the Russian Empire), was an actress in several Yiddish theater companies in Warsaw and Lodz. The family had already been the victim of anti-semitic violence in Bessarabia – some members of his family were killed during the Kishinev pogrom. One of the composer’s cousins (a son of his father’s sister Khaya Vaynberg) – Isay Abramovich Mishne – was the secretary of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Baku Soviet commune and was executed in 1918 along with the other 26 Baku Commissars

Weinberg entered the Warsaw Conservatory at the age of twelve, studying piano under Józef Turczyński, and graduated in 1939. Two works (his first string quartet and a berceuse for piano) were composed before he fled to the Soviet Union at the outbreak of World War II. His parents and younger sister Esther, who remained behind, were interned at the Lodz ghetto and subsequently perished in the Trawniki concentration camp. Weinberg first settled in Minsk, where he studied composition under Vasily Zolotarev for the first time at the Conservatory there. At the outbreak of World War II on Soviet territory, Weinberg was evacuated to Tashkent (Central Asia), where he wrote works for the opera, as well as met and married Solomon Mikhoels‘ daughter Natalia Vovsi. There he also met Dmitri Shostakovich who was impressed by his talent and became his close friend. Meeting Shostakovich had a profound effect on the younger man, who said later that, “It was as if I had been born anew”. In 1943, he moved to Moscow at Shostakovich’s urging.

Later life in Russia

Once in Moscow, Weinberg began to settle down and to work energetically, as evidenced by his increasing opus numbers: approximately 30 works from 1943 until 1948. Several of Weinberg’s works were banned during the Zhdanovshchina of 1948, and, as a result, he was almost entirely ignored by the Soviet musical establishment; for a time he could make a living only by composing for the theatre and circus. On 13 January 1948 Weinberg’s father-in-law Mikhoels was assassinated in Minsk on Stalin‘s orders; shortly after Mikhoels’s murder, Soviet agents began following Weinberg. In February 1953, he was arrested on charges of “Jewish bourgeois nationalism” in relation to the murder of his father-in-law as a part of the so-called “Doctors’ plot“: Shostakovich allegedly wrote to Lavrenti Beria to intercede on Weinberg’s behalf, as well as agreeing to look after Weinberg’s daughter if his wife were also arrested. In the event, he was saved by Stalin’s death the following month, and he was officially rehabilitated shortly afterwards.

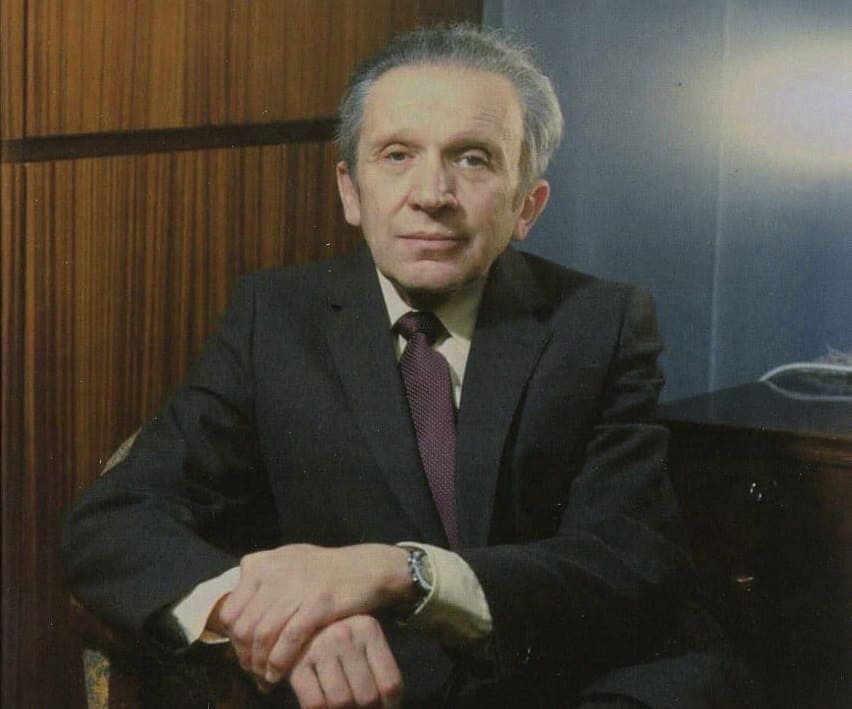

Thereafter Weinberg continued to live in Moscow, composing and occasionally performing as a pianist. He and Shostakovich lived near to one another, sharing ideas on a daily basis. Besides the admiration which Shostakovich frequently expressed for Weinberg’s works, they were taken up by some of Russia’s foremost performers and conductors, including Emil Gilels, Leonid Kogan, Kirill Kondrashin, Mstislav Rostropovich, Kurt Sanderling, and Thomas Sanderling.

Final years and posthumous reception

Towards the end of his life, Weinberg suffered from Crohn’s disease and remained housebound for the last three years, although he continued to compose. He converted to Orthodox Christianity on 3 January 1996, less than two months before his death in Moscow. His funeral was held in the Church of the Resurrection of the Word.

A 2004 reviewer has considered him as “the third great Soviet composer, along with Prokofiev and Shostakovich”. Ten years after his death, a concert premiere of his opera The Passenger in Moscow sparked a posthumous revival. The British director David Pountney staged the opera at the 2010 Bregenz Festival and restaged it at English National Opera in 2011. Thomas Sanderling has called Weinberg “a great discovery. Tragically, a discovery, because he didn’t gain much recognition within his lifetime besides from a circle of insiders in Russia.”

Conversion to Christianity

Posthumously, Weinberg’s conversion to Christianity has been the subject of some controversy. In particular, Weinberg’s first and older daughter, Victoria, questioned in an interview from 2016 whether his baptism was undertaken voluntarily in light of his long-standing illness, and in his book on the composer, David Fanning alludes to rumors that Weinberg was baptised under pressure from his second wife, Olga Rakhalskaya. However, Olga Rakhalskaya has subsequently replied to these allegations by stating that involuntary baptism (under pressure or when mentally incapacitated) is sinful and of no value, and that Weinberg had been considering his conversion for about a year before he asked to be baptised in late November 1995.The composer’s younger daughter, Anna Weinberg, has written that “father was baptized in sound mind and firm memory, without the slightest pressure from any side; this was his deliberate and conscious decision, and why he did it is not for us to judge.”. It is quite possible that the composer’s interest in Christianity began when working on the film score for Boris Yermolaev‘s “Отче Наш” (Otche Nash, “Our Father in Heaven”) in the late 1980s. A setting of the Lord’s Prayer appears in the manuscript version of Weinberg’s last completed symphony (No. 21, 1991), subtitled “Kaddish“.

Works

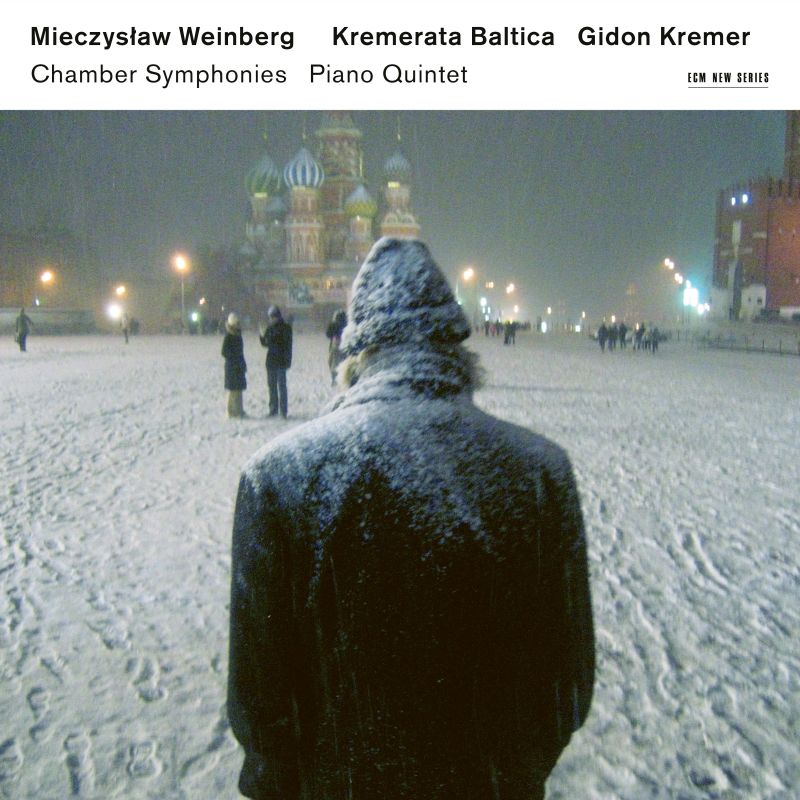

Weinberg’s output includes twenty-two symphonies, other works for orchestra (including four chamber symphonies and two sinfoniettas), seventeen string quartets, eight violin sonatas (three solo and five with piano), twenty-four preludes for cello and six cello sonatas (two with piano and four solo), four solo viola sonatas, six piano sonatas, numerous other instrumental works, as well as more than 40 film and animation scores (including The Cranes are Flying, Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, 1958). He wrote seven operas, and considered one of them, The Passenger (Passazhirka) (written in 1967-68, premiered in 2006), to be his most important work The British record label Olympia was among the first to raise general awareness of Weinberg in the late 1990s and early 2000s through a series of seventeen compact disc recordings of his music (plus one sampler disc), consisting of both original recordings and re-masterings of earlier Melodiya LPs. Since then, numerous other labels have recorded Weinberg’s music, including Naxos, Chandos, ECM and Deutsche Grammophon.

Weinberg’s works sometimes have a strong element of commemoration, with reference to his formative years in Warsaw and to the war which ended that earlier life. Typically, however, this darkness serves as a background to the finding of peace through catharsis. This desire for harmony is also evident in his musical style; Lyudmilla Nikitina emphasizes the “neo-classical, rationalist clarity and proportion” of his works.

More generally, Weinberg’s style can be described as modern yet accessible. His harmonic language is usually based on an expanded/free tonality mixed with occasional polytonality (e.g. as in the Twentieth Symphony) and atonality (e.g. as in the Twelfth String Quartet or the 24 Preludes for Solo Cello). His earlier works exhibit neo-Romantic tendencies and draw significantly on folk-music, whereas his later works, which came with improved social circumstances and greater compositional maturity, are more complex and austere. However, even in these later, more experimental works from the late 1960s, 70s and 80s (e.g. the Third Violin Sonata or the Tenth Symphony), which make liberal use of tone clusters and other devices, Weinberg retains a keen sense of tradition that variously manifests itself in the use of classical forms, more restrained tonality, or lyrical melodic lines. Always masterfully crafted, many of his instrumental works contain highly virtosic writing and make significant technical demands on performers.

Shostakovich and stylistic influences

Although he never formally studied with Shostakovich, the older composer had an obvious influence on Weinberg’s music. This is particularly noticeable in his Twelfth Symphony (1975–1976, Op. 114), which is dedicated to the memory of Shostakovich and quotes from a number of the latter’s works. Other explicit connections include the pianissimo passage with celesta which ends the Fifth Symphony (1962, Op. 76), reminiscent of Shostakovich’s Fourth; the quote from one of Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues in Weinberg’s Sixth Piano Sonata (1960, Op. 73); and numerous, strung-together quotes from Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto and Cello Sonata (4th movement) in Weinberg’s 21st Prelude for Solo Cello. These explicit connections should not be interpreted, however, to mean that musical influences went in only one direction (from Shostakovich to Weinberg). Indeed, Shostakovich drew significant inspiration from Weinberg’s Seventh Symphony for his Tenth String Quartet; Shostakovich also drew on some of the ideas in Weinberg’s Ninth String Quartet for the slow movement of his Tenth Quartet (opening bars of Weinberg’s Ninth), for his Eleventh Quartet (first movement of Weinberg’s Ninth) and for his Twelfth Quartet (F-sharp major ending); and in his First Cello Concerto of 1959, Shostakovich re-used Weinberg’s idea of a solo cello motif in the first movement that recurs at the end of the work to impart unity, from Weinberg’s Cello Concerto (1948, Op. 43).

It is also important to note that Weinberg does not restrict himself to quoting Shostakovich. For example, Weinberg’s Trumpet Concerto quotes Mendelssohn‘s well-known Wedding March; his Second Piano Sonata (written in 1942, before moving to Moscow) quotes Haydn; and his Twenty First Symphony quotes a Chopin ballade. Such cryptic quotations are stylistic features shared by both Weinberg and Shostakovich.

The discussion above highlights that mutual influences and stylistic affinities can be found in many works by the two composers, no doubt as a result of their close friendship and similar compositional views (see also ).

More general similarities in musical language between Shostakovich and Weinberg include the use of extended melodies, repetitive themes, and methods of developing the musical material. However, Nikitina states that “already in the 60s it was obvious that Weinberg’s style was individual and essentially different from the style of Shostakovich.”.

Along with Shostakovich, Nikitina identifies Prokofiev, Myaskovsky, Bartók and Mahler as formative influences. Ethnic influences include not only Jewish music, but also Moldavian, Polish, Uzbek, and Armenian elements. Weinberg has been identified by a number of critics as the source of Shostakovich’s own increased interest in Jewish themes.

Operas

- The Passenger, Op. 97 (1967/68) after the book by Zofia Posmysz

- The Madonna and the Soldier «Мадонна и солдат», Op. 105 to a libretto by Alexander Medvedev (1970)

- The Love of d’Artagnan «Любовь Д’Артаньяна», after The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas (1971)

- Pozdravlyayem! «Поздравляем!», Op. 111 after Mazel Tov by Sholem Aleichem (1975)

- Lady Magnesia «Леди Магнезия», Op. 112 after Passion, Poison and Petrifaction by George Bernard Shaw (1975)

- The Portrait, Op. 128 after Nikolai Gogol (1980)

- The Idiot, Op. 144 after Dostoyevsky (1985)

Selected recordings

- Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op.10, 1942; Symphony for string orchestra & harpsichord No. 7 in C major, Op. 81, 1964: Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Thord Svedlund (cond.), Chandos, 2010.

- Sonata For Clarinet & Piano (1945): Joaquin Valdepenas (clarinet), Dianne Werner (piano); Jewish Songs after Shmuel Halkin (1897–1960) for voice & piano, Op. 17 (1944): Richard Margison (tenor), Dianne Werner (piano); Piano Quintet (1944), Op. 18: ARC Ensemble, 2006.

- Symphony No. 17, Op. 137 “Memory”; Symphonic Poem, Op. 143 “The Banners of Peace”: USSR Radio Symphony Orchestra, Vladimir Fedoseyev (cond.), Olympia OCD 590, 1996.

Complete editions

- Complete Works for Solo Cello (24 Preludes and Four Sonatas): Yosif Feigelson, Naxos, 1996.

- Complete String Quartets Vol. 1 – 6: Quatuor Danel, CPO, 2008-2012.

- Complete Songs Vol. 1: Olga Kalugina (soprano) and Svetlana Nikolayeva (mezzo-soprano), Dmitri Korostelyov (piano), Toccata Classics (with Russian sung texts and translations), 2008.

Video

- Opera The Passenger, Op. 97 (1967/68) sung in German, Polish, Russian, French, English, Czech, and Yiddish: Michelle Breedt, Elena Kelessidi, Roberto Sacca, Prague Philharmonic Choir, Vienna Symphony Orchestra Teodor Currentzis (cond.), David Pountney (dir.) at the Bregenzer Festspiele, 2010 (Non-DVD compatible Blu-ray). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mieczys%C5%82aw_Weinberg

Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra & Choir conducted by Antoni Wit

I – Podmuch wiosny (Gust of Spring): 0:00 II – Baluckie dzieci (Children of Baluty): 3:54 III – Przed stara chata (In Front of the Old Hut): 7:55 IV – Byl sad (There was an Orchard): 11:54 V – Bez (Elderberry): 17:07 VI – Lekcja (Lesson): 20:23 VII – Warszawskie psy (Warsaw Dogs): 27:56 VIII – Matka (Mother): 33:39 IX – Sprawiedliwosc (Justice): 40:04 X – Wisla plynie (The Vistula flows): 46:19

Weinberg’s Symphony No.8 was written in 1964, being his first fully choral symphony. It uses a tenor, soprano, alto as well as a mixed choir. The text belongs to the Polish poet of Jewish origin, Julian Tuwim, one of Weinberg’s favorites. It premiered in Moscow on March 6, 1966, performed by the Russian Academic Choir and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Alexander Yurlov.

Weinberg remembered his old homeland who he had abandoned in 1939, to which he did not return until 1964 during a visit to the Warsaw Autumn Festival. In the style of one of Shostakovich’s symphonies, it is structured in a series of ten movements, in the form of a collection of descriptive songs. “Kwiaty Polskie” (Polish Flowers), written between 1940 and 1946, is an epic poem, presenting a history and criticism of Poland during the time between the two world wars.

The first movement, Gust of Spring, sets the tone for the work as a whole with its reflections on Poland’s troubled past and ominous future. It begins pensively with female voices sounding plaintively over tolling lower strings and percussion, the former continuing at length until strings have an elegiac response that is continued by solo clarinet towards the close.

The second movement, Children of Bałuty, evokes the social inequities of pre-war Poland as seen through the industrial landscape of Bałuty, a suburb of Łódź. It commences with lively and rhythmically agile writing for female voices over a pizzicato accompaniment which soon draws in the strings and woodwind. A pause and then the tenor soloist responds in more immediately expressive terms, before elements of both themes are briefly combined prior to the brusque ending.

The third movement, In Front of the Old Hut, surveys the degradation endured by the mass of Polish people in earlier times. It starts with plangent woodwind entries that are joined by solo tenor in an almost Baroque-like texture, offset by discreet gestures on percussion. Strings and muted brass enter before unaccompanied voices bring about a hushed conclusion.

The fourth movement, There was an Orchard, expands on the issue of poverty with its depiction of the squalor common to peasants, gypsies and Jews alike. It begins with a burgeoning of folk-like gestures on woodwind and strings, the chorus entering stealthily, followed by a dialogue for soprano and mezzo soloists from within the chorus. The emotional mood heightens only gradually, with the instrumental component becoming more forceful prior to its sudden curtailment.

The fifth movement, Elderberry, contrasts the hope offered by springtime with the alienation of urban life. It commences with solo tenor accompanied by wistful woodwind gestures over a chord in lower strings. The chorus responds in almost prayerful terms, leading on to the work’s initial climax in which the whole orchestra is also to be heard for the first time.

The sixth movement, Lesson, is a warning to Polish infants of the inequities that they are to encounter. It opens with dance-like music for chorus and orchestra, percussion much in evidence. This tails off to leave the chorus sounding hesitant over fragmentary gestures on woodwind and brass, before the activity resumes on orchestra alone. The chorus then re-emerges at its height, after which calmer yet sombre exchanges between brass and percussion gradually subside into nothingness.

The seventh movement, Warsaw Dogs, equates the cruelties dealt out to dogs with that of the Polish people in time of war. It launches with stark unison chords on piano and percussion, chorus and woodwind replying with similarly forceful writing which builds in intensity until the initial chords are hammered out by full orchestra. An impassioned tenor solo brings a sudden hush, with only fugitive gestures from voices and instruments remaining prior to a powerful orchestral chord.

The eighth movement, Mother, takes the murder of a woman at her son’s grave as emblematic of the atrocities inflicted by the Nazi invaders. It unfolds with an eloquent solo from tenor over static chords, derived from that which ended the preceding movement on lower (wordless) voices and instruments. At length a solo horn and then upper strings wearily assume the melodic foreground, followed by glacial gestures on celesta and lower woodwind as a rounding off.

this symphony was written in the same year (1976) as Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs ~David A

Mieczysław (Moisey) Weinberg (Vainberg) (1919-1996) – String Quartet n°5 in B flat major, op. 27 (1945) Quatuor Danel: 1st Violin- Marc Danel 2nd Violin- Gilles Millet Viola- Vlad Bogdanas Cello- Guy Danel I. Melodia 0:01 II. Humoreska 5:54 III. Scherzo 11:31 IV. Improvisation 13:51 V. Serenata 18:42

CD Project for NAXOS Mieczysław Weinberg » A Clarinet showcase « Robert Oberaigner, clarinet Michail Jurowski, conductor Michael Schöch, piano Dresden Chamber Soloists