Wilhelm Furtwängler 25 January 1886 – 30 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major influence for many later conductors, and his name is often mentioned when discussing their interpretative styles.

Furtwängler was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic between 1922 and 1945, and from 1952 until 1954. He was also principal conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra (1922–26), and was a guest conductor of other major orchestras including the Vienna Philharmonic.

Although he was not an adherent of Nazism, he was the leading conductor to remain in Germany during the Nazi regime. This decision caused lasting controversy, and the extent to which his presence lent prestige to the Third Reich is still debated.

Life and career

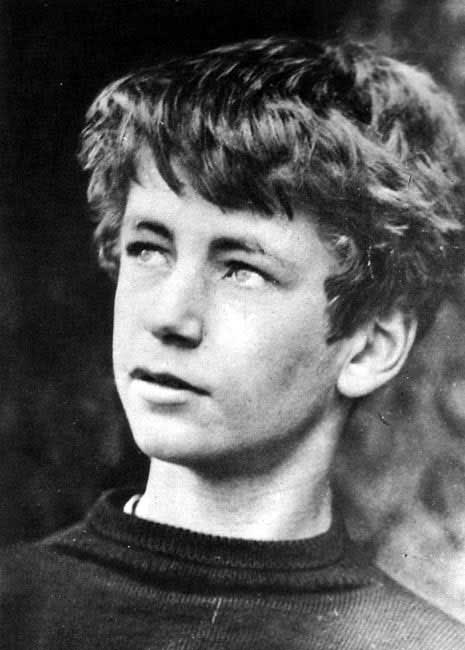

Wilhelm Furtwängler was born in Schöneberg (now a district/borough of Berlin) into a prominent family. His father Adolf was an archaeologist, his mother a painter. Most of his childhood was spent in Munich, where his father taught at the city’s Ludwig Maximilian University. He was given a musical education from an early age, and developed an early love of Ludwig van Beethoven, a composer with whose works he remained closely associated throughout his life.

Although Furtwängler achieved fame chiefly from his conducting, he regarded himself foremost as a composer. He began conducting in order to perform his own works. By age of twenty, he had composed several works. However, they were not well received, and that, combined with the financial insecurity of a career as a composer, led him to concentrate on conducting. He made his conducting debut with the Kaim Orchestra (now the Munich Philharmonic) in Anton Bruckner‘s Ninth Symphony. He subsequently held conducting posts at Munich, Strasbourg, Lübeck, Mannheim, Frankfurt, and Vienna.

Furtwangler succeeded Artur Bodanzky as principal conductor of the Mannheim Opera and Music Academy in 1915, remaining until 1920. As a boy he had sometimes stayed with his grandmother in Mannheim. Through her family he met the Geissmars, a Jewish family who were leading lawyers and amateur musicians in the town. Berta Geissmar wrote, “Furtwängler became so good at skiing as to attain almost professional skill…Almost every sport appealed to him: he loved tennis, sailing and swimming…He was a good horseman…” She also reports that he was a strong mountain climber and hiker.

Berta Geissmar subsequently became his secretary and business manager, in Mannheim and later in Berlin, until she was forced to leave Germany in 1935 From 1921 onwards, Furtwängler shared holidays in the Engadin with Berta and her mother. In 1924 he bought a house there. After he married, the house was open to a wide circle of friends.

In 1920 he was appointed conductor of the Berlin Staatskapelle succeeding Richard Strauss. In January 1922, following the sudden death of Arthur Nikisch, he was appointed to the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Shortly afterwards he was appointed to the prestigious Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, again in succession to Nikisch. Furtwängler made his London debut in 1924, and continued to appear there before the outbreak of World War II as late as 1938, when he conducted Richard Wagner‘s Ring. (Furtwängler later conducted in London many times between 1948 and 1954). In 1925 he appeared as guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, making return visits in the following two years.

In January 1945 Furtwängler fled to Switzerland. It was during this period that he completed what is considered his most significant composition, the Symphony No. 2 in E minor. It was given its premiere in 1948 by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Furtwängler’s direction and was recorded for Deutsche Grammophon.

Following the war, he resumed performing and recording, and remained a popular conductor in Europe, although his actions in the 1930s and 40s were a subject of ongoing criticism. He died in 1954 in Ebersteinburg, close to Baden-Baden. He is buried in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof. His second wife Elisabeth died in 2013, aged 103, outliving him by 59 years.

Third Reich controversy

First confrontations with the Nazis

Furtwängler was very critical of Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany, and was convinced that Hitler would not stay in power for long. He had said of Hitler in 1932, “This hissing street pedlar will never get anywhere in Germany”.

As the antisemitic policies of the Third Reich took effect, Jewish musicians were forced out of work and began to leave Germany. The Nazis were aware that Furtwängler was opposed to the policies and might also decide to go abroad, so the Berlin Philharmonic, which employed many Jews, was exempted from the policies. In 1933, when Bruno Walter was dismissed from his position as principal conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the Nazis asked Furtwängler to replace him for an international tour. Their goal was to show to the world that Germany did not need Jewish musicians. Furtwängler refused, and it was Richard Strauss who replaced Walter.

On 10 April 1933, Furtwängler wrote a public letter to Goebbels to denounce the new rulers’ antisemitism:

Ultimately there is only one dividing line I recognize: that between good and bad art. However, while the dividing line between Jews and non-Jews is being drawn with a downright merciless theoretical precision, that other dividing line, the one which in the long run is so important for our music life, yes, the decisive dividing line between good and bad, seems to have far too little significance attributed to it […] If concerts offer nothing then people will not attend; that is why the QUALITY is not just an idea: it is of vital importance. If the fight against Judaism concentrates on those artists who are themselves rootless and destructive and who seek to succeed in kitsch, sterile virtuosity and the like, then it is quite acceptable; the fight against these people and the attitude they embody (as, unfortunately, do many non-Jews) cannot be pursued thoroughly or systematically enough. If, however, this campaign is also directed at truly great artists, then it ceases to be in the interests of Germany’s cultural life […] It must therefore be stated that men such as Walter, Klemperer, Reinhardt etc. must be allowed to exercise their talents in Germany in the future as well, in exactly the same way as Kreisler, Huberman, Schnabel and other great instrumentalists of the Jewish race. It is only just that we Germans should bear in mind that in the past we had Joseph Joachim one of the greatest violinists and teachers in the German classical tradition, and in Mendelssohn even a great German composer – for Mendelssohn is a part of Germany’s musical history”.

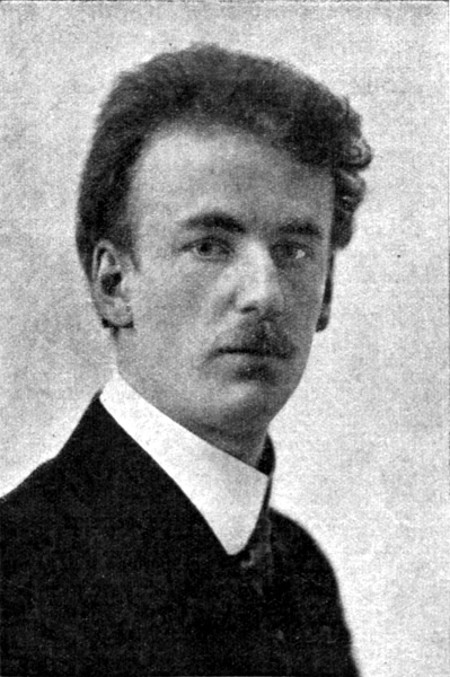

As stated by the historian F. Prieberg, this letter proved that if the concepts of nation and patriotism had a deep meaning for him, “it is clear that race meant nothing to him”. In June 1933, for a text which was to be the basis for a discussion with Goebbels, Furtwängler went further, writing, “The Jewish question in musical spheres: a race of brilliant people!” He threatened that if boycotts against Jews were extended to artistic activities, he would resign all his posts immediately, concluding that “at any rate to continue giving concerts would be quite impossible without [the Jews] – to remove them would be an operation which would result in the death of the patient.”[ Etching of Furtwängler from 1928

Because of his high profile, Furtwängler’s public opposition prompted a mixed reaction from the Nazi leadership. Heinrich Himmler wished to send Furtwängler to a concentration camp. Goebbels and Göring ordered their administration to listen to Furtwängler’s requests and to give him the impression that they would do what he asked. This led him to believe that he had some positive influence to stop the racial policy. He subsequently invited several Jewish and anti-fascist artists (such as Yehudi Menuhin, Artur Schnabel, and Pablo Casals) to perform as soloists in his 1933/34 season, but they refused to come to Nazi Germany. Furtwängler subsequently invited Jewish musicians from his orchestra such as Szymon Goldberg to play as soloists.

The Gestapo built a case against Furtwängler, noting that he was providing assistance to Jews. Furtwängler gave all his fees to German emigrants during his concerts outside Germany. The German literary scholar Hans Mayer was one of these emigrants. Mayer later observed that for performances of Wagner operas in Paris prior to the war, Furtwängler cast only German emigrants (Jews or political opponents to the third Reich) to sing. Georg Gerullis, a director at the Ministry of Culture remarked in a letter to Goebbels, “Can you name me a Jew on whose behalf Furtwängler has not intervened?”[

Furtwängler never joined the Nazi Party. He refused to give the Nazi salute, to conduct the Horst-Wessel-Lied, or to sign his letters with “Heil Hitler”, even those he wrote to Hitler. F. Prieberg has found all the letters from the conductor to the dictator: these are always requests for an audience to defend Jewish musicians or musicians considered to be “degenerate”. The fact that he refused to sign by ‘Heil Hitler’ was considered a major affront by the Nazi leadership and explains that many of these requests for a hearing were refused. However, Furtwängler was appointed as the first vice-president of the Reichsmusikkammer and Staatsrat of Prussia, and accepted these honorary positions to try to bend the racial policy of Nazis in music and to support Jewish musicians. For concerts in London and Paris before the war, Furtwängler refused to conduct the Nazi anthems or to play music in halls adorned with swastikas During the universal exposition held in Paris in 1937, a picture of the German delegation was taken in front of the Arc de Triomphe. In the picture, Furtwängler is the only German not giving the Nazi salute (he has his hand on his shoulder). This picture was suppressed at the time. The photo was, moreover, carefully preserved by the Gestapo, providing new proof that Furtwängler was opposed to Nazi policy.

In 1933, Furtwängler met with Hitler to try to stop the new antisemitic policy in the domain of music. He had prepared a list of significant Jewish musicians: these included the composer Arnold Schoenberg, the musicologist Curt Sachs, the violinist Carl Flesch, and Jewish members of the Berlin Philharmonic. Hitler did not listen to Furtwängler, who lost patience, and the meeting became a shouting match. Berta Geissmar wrote, “After the audience, he told me that he knew now what was behind Hitler’s narrow-minded measures. This is not only antisemitism, but the rejection of any form of artistic, philosophical thought, the rejection of any form of free culture…”

Mannheim Concert

On 26 April 1933, Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic performed a joint concert in Mannheim with the local orchestra to mark the 50th anniversary of Wagner’s death and to raise money for the Mannheim orchestra. The concert had been organised before the Nazis came to power. The Nazified Mannheim Orchestra Committee demanded that the Jewish leader of the Berlin orchestra, Szymon Goldberg, give way to the leader of the Mannheim orchestra for the evening. Furtwängler refused, and the concert took place as planned.

Before the banquet organized for the evening, members of the Mannheim Orchestra Committee came to remonstrate with Furtwängler, accusing him of “a lack of national sentiment”. Furtwängler furiously left before the banquet to rejoin Berta Geissmar and her mother. The fact that Furtwängler had preferred to spend the evening with his “Jewish friends” rather than with Nazi authorities caused a controversy. He subsequently refused to conduct again in Mannheim,[35][36] only returning 21 years later in 1954.

“The Hindemith Case”

In 1934, Furtwängler publicly described Hitler as an “enemy of the human race” and the political situation in Germany as a “Schweinerei” (“disgrace”, literally: “swinishness”).

On 25 November 1934, he wrote a letter in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, “Der Fall Hindemith” (“The Hindemith Case”), in support of the composer Paul Hindemith. Hindemith had been labelled a degenerate artist by the Nazis. Furtwängler also conducted a piece by Hindemith, Mathis der Maler, although the work had been banned by the Nazis The concert received enormous acclaim and unleashed a political storm. The Nazis (especially Alfred Rosenberg, the Nazi Party’s chief racial theorist) formed a violent conspiracy against the conductor, who resigned from his official positions, including his titles as vice-president of the Reichsmusikkammer and of Staatsrat of Prussia. His resignation from the latter position was refused by Göring. He was also forced by Goebbels to give up all his artistic positions.

Furtwängler decided to leave Germany, but the Nazis prevented him. They seized the opportunity to “aryanise” the orchestra and its administrative staff. Most of the Jewish musicians of the orchestra had already left the country and found positions outside Germany, with Furtwängler’s assistance.

The main target of the Nazis was Berta Geissmar. She was so close to the conductor that she wrote in her book about Furtwängler that the Nazis had begun an investigation to know if she was his mistress. After being harassed for a period of two years, she moved to London when she became Sir Thomas Beecham‘s main assistant. In the book she wrote on Furtwängler in England in 1943, she said:

Furtwängler, although he had decided to remain in Germany, was certainly no Nazi … He had a private telephone line to me which was not connected via the exchange… Before going to bed, he used to chat with me over telephone. Sometimes I told him amusing stories to cheer him up, sometimes we talked about politics. One of the main threats the Nazis used against Furtwängler and myself later on was the assertion that they had recorded all these conversations. I should not have thought that it was possible! Was there enough shellac? If the Nazis really did this, their ears must certainly have burnt, and it was not surprising that Furtwängler was eventually put on their black list, let alone myself.

Goebbels refused to meet Furtwängler to clarify his situation for several months. During the same period, many members of the orchestra and of his public were begging him not to emigrate and desert them. In addition, Goebbels sent him a clear signal that if he left Germany he would never be allowed back, frightening him with the prospect of permanent separation from his mother (to whom he was very close) and his children Furtwängler considered himself responsible for the Berlin Philharmonic and for his family, and decided to stay.

The compromise of 1935

On 28 February 1935, Furtwängler met Goebbels, who wanted to keep Furtwängler in Germany, since he considered him, like Richard Strauss and Hans Pfitzner, a “national treasure”. Goebbels asked him to pledge allegiance publicly to the new regime. Furtwängler refused. Goebbels then proposed that Furtwängler acknowledge publicly that Hitler was in charge of cultural policy. Furtwängler accepted: Hitler was a dictator and controlled everything in the country. But he added that it must be clear that he wanted nothing to do with the policy and that he would remain as a non-political artist, without any official position.The agreement was reached. Goebbels made an announcement declaring that Furtwängler’s article on Hindemith was not political: Furtwängler had spoken only from an artistic point of view, and it was Hitler who was in charge of the cultural policy in Germany.

Goebbels did not reveal the second part of the deal. However, the agreement between them was largely respected. At his subsequent denazification trial, Furtwängler was charged with conducting only two official concerts for the period 1933–1945. Furtwängler appeared in only two short propaganda films.

Other Nazi leaders were not satisfied with the compromise, since they believed that Furtwängler had not capitulated: Rosenberg demanded in vain that Furtwängler apologise to the regime. Goebbels, who wanted to keep Furtwängler in Germany, wrote in his diary that he was satisfied with the deal and laughed at “the incredible naïvety of artists”.

Hitler now allowed him to have a new passport. When they met again in April, Hitler attacked Furtwängler for his support of modern music, and made him withdraw from regular conducting for the time being, save for his scheduled appearance at Bayreuth. However, Hitler confirmed that Furtwängler would not be given any official titles, and would be treated as a private individual. But Hitler refused Furtwängler’s request to announce this, saying that it would be harmful for the “prestige of the State”.

Furtwängler resumed conducting. On 25 April 1935, he returned to the Berlin Philharmonic with a program dedicated to Beethoven. Many people who had boycotted the orchestra during his absence came to the concert to support him. He was called out seventeen times. On 3 May, in his dressing room before conducting the same program, he was informed that Hitler and his entire staff would attend the concert. He was given the order to welcome Hitler with the Nazi salute. Furtwängler was so furious that he ripped the wooden panelling off a radiator. Franz Jastrau, the manager of the orchestra, suggested that he keep his baton in his right hand all the time. When he entered the hall, all the Nazi leaders were present making the Hitler salute, but Furtwängler kept hold of his baton and began the concert immediately. Hitler probably could not have imagined that such an affront was possible but decided to put up a good show: he sat down and the concert went on

At the end of the concert, Furtwängler continued to keep his baton in his right hand. Hitler understood the situation and jumped up and demonstratively held out his right hand to him. The same situation occurred during another concert later on, when a photographer had been mobilized by the Nazis for the occasion: the photo of the famous handshake between Furtwängler and Hitler was distributed everywhere by Goebbels. Goebbels had obtained what he desired: to keep Furtwängler in Germany and to give the impression to those who were not well informed (especially outside the country) that Furtwängler was now a supporter of the regime.

Furtwängler wrote in his diary in 1935 that there was a complete contradiction between the racial ideology of the Nazis and the true German culture, the one of Schiller, Goethe and Beethoven. He added in 1936: “living today is more than ever a question of courage”.

The New York Philharmonic Orchestra

In September 1935, the baritone Oskar Jölli, a member of the Nazi party, reported to the Gestapo that Furtwängler had said, “Those in power should all be shot, and things in Germany would not change until this was done”. Hitler forbade him to conduct for several months, until Furtwängler’s fiftieth birthday in January 1936. Hitler and Goebbels allowed him to conduct again and offered him presents: Hitler an annual pension of 40,000 Reichsmarks, and Goebbels an ornate baton made of gold and ivory. Furtwängler refused them.

Furtwängler was offered the principal conductor’s post at the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, which was then the most desirable and best paid position in international musical life. He was to have followed Arturo Toscanini, who had declared that Furtwängler was the only man to succeed him. Furtwängler accepted the post, but his telephone conversations were recorded by the Gestapo.

While Furtwängler was travelling, the Berlin branch of the Associated Press leaked a news story on Hermann Göring‘s orders. It suggested Furtwängler would probably be reappointed as director of the Berlin State Opera and of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.This caused the mood in New York to turn against him: it seemed that Furtwängler was now a supporter of the Nazi Party. On reading the American press reaction, Furtwängler chose not to accept the position in New York. Nor did he accept any position at the Berlin Opera.

1936 to 1937

Furtwängler included Jewish and other “non-Aryan” musicians during his overseas tours in the 1930s. This was the case in France in April 1934 where he conducted operas by Wagner. Hans Mayer, a professor of literature, a communist Jew exiled from Germany, reported after the war that Furtwängler had voluntarily chosen a cast made up almost entirely of Jews or of people driven out of Germany during these concerts. Likewise, during the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937, Furtwängler performed a series of Wagnerian concerts which were a triumph. Goebbels announced in the German press that Furtwängler and Wagner had been acclaimed in Paris. In fact, those who made Furtwängler a triumph were precisely German exiles, including many Jews, who lived in Paris and who saw Furtwängler as a symbol of anti-Nazi Germany. Furtwängler also refused to conduct the Nazi anthem and demanded that all swastikas be removed from his concert halls The Nazis realized and complained that Furtwängler did not bring back any money from his tours abroad. They initially believed that Furtwängler was spending everything for him, and later realized that he was giving all the money to the German emigrants. It confirmed after the war that the conductor gave them everything he had “to the last penny” when he met them. Furtwängler always refused to practice the Nazi salute and conduct the Nazi hymns. When the Berlin orchestra performed abroad, he had to start the concert with the Nazi anthem Horst-Wessel-Lied. As the English and French could see during the period 1935–1939, Furtwängler was replaced by the steward Hans von Benda and only entered the room afterwards.

Furtwängler conducted at the Bayreuth festival in 1936 for the first time since 1931, in spite of his poor relationship with Winifred Wagner. Here, he conducted a new staging of Lohengrin (the first time this work was performed at the festival since 1909) for which Hitler ensured no expense was spared; the costume and set design were on a larger and more expensive scale than anything previously seen at Bayreuth. This performance was broadcast throughout Europe and in the Americas, and was used as part of a propaganda effort intended to portray the “New Germany” as the triumphant inheritor of the German musical tradition rather than a break from the past, to which Furtwängler’s place at the podium was instrumental. Both Hitler and Goebbels attended the festival and attempted to force him to accept an official position. Friedelind Wagner, the composer’s anti-Nazi granddaughter, witnessed a meeting between Hitler and Furtwängler at her mother’s Bayreuth home:

I remember Hitler turning to Furtwängler and telling him that he would now have to allow himself to be used by the party for propaganda purposes, and I remember that Furtwängler refused categorically. Hitler flew into a fury and told Furtwängler that in that case there would be a concentration camp ready for him. Furtwängler quietly replied: “In that case, Herr Reichskanzler, at least I will be in very good company.” Hitler couldn’t even answer, and vanished from the room.

Furtwängler avoided the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, and canceled all his public engagements during the following winter season in order to compose. He returned to the Berlin Philharmonic in 1937, performing with them in London for the coronation of George VI, and in Paris for the universal exposition, where he again refused to conduct the Horst-Wessel-Lied or to attend the political speeches of German officials.

The Salzburg Festival was considered to be a festival of the “free world” and a centre for anti-fascist artists. Hitler had forbidden all German musicians from performing there. In 1937, Furtwängler was asked to conduct Beethoven’s ninth symphony in Salzburg. Despite strong opposition from Hitler and Goebbels, he accepted the invitation.

Arturo Toscanini, a prominent anti-fascist, was furious to learn that Furtwängler would be at the Festival. He accepted his engagement in Salzburg on the condition that he would not have to meet Furtwängler. But the two did meet, and argued over Furtwängler’s actions. Toscanini argued: “I know quite well that you are not a member of the Party. I am also aware that you have helped your Jewish friends […] But everyone who conducts in the Third Reich is a Nazi!”. Furtwängler emphatically denied this and said: “By that, you imply that art and music are merely propaganda, a false front, as it were, for any Government which happens to be in power. If a Nazi Government is in power, then, as a conductor, I am a Nazi; under the communists, I would be a Communist; under the democrats, a democrat… No, a thousand times no! Music belongs to a different world, and is above chance political events.” Toscanini disagreed and that ended the discussion.

Furtwängler returned to the Bayreuth festival, his relationship with Winifred Wagner worse than ever. He did not appear again in Bayreuth until 1943. He wrote a letter to Winifred Wagner, sending copies to Hitler, Göring and Goebbels, accusing her of having betrayed Wagner’s heritage by applying racial and not artistic rules in the choice of the artists, and of putting her “trust in the powers of an authoritarian state”. This clear attack on Hitler caused a sharp reaction: Hitler wanted to drop Furtwängler from Bayreuth after all. Goebbels wrote in two entries of his diary in 1937 that Furtwängler was constantly helping Jews, “half-Jews” and “his small Hindemith”.

According to the historian Fred Prieberg, by the end of 1937 nobody who was correctly informed could accuse Furtwängler of working for the Nazis. For the Nazi leadership, especially for Hitler, it became necessary to prove to him that he was not irreplaceable.

Herbert von Karajan

The Nazi leaders searched for another conductor to counterbalance Furtwängler. A young, gifted Austrian conductor now appeared in the Third Reich: Herbert von Karajan. Karajan had joined the Nazi Party early and was much more willing to participate in the propaganda of the new regime than Furtwängler.

Furtwängler had attended several of his concerts, praising his technical gifts but criticizing his conducting style; he did not consider him a serious competitor. However, when Karajan conducted Fidelio and Tristan und Isolde in Berlin in late 1938, Göring decided to take the initiative.The music critic Edwin von der Nüll wrote a review of these concerts with the support of Göring. Its title, “The Karajan Miracle”, was a reference to the famous article “The Furtwängler Miracle” that had made Furtwängler famous as a young conductor in Mannheim. Von der Nüll championed Karajan saying, “A thirty-year-old man creates a performance for which our great fifty-year-olds can justifiably envy him”. Furtwängler’s photo was printed next to the article, making the reference clear.

The article was part of a broader attack made against Furtwängler. The Nazi press criticized him for being “a man of the Nineteenth century” whose political ideas were obsolete and who did not understand and accept the new changes in Germany. The situation became intolerable for Furtwängler. He obtained from Goebbels a pledge to cease these attacks.

However, Furtwängler’s position was weakened: he knew that if he left Germany, Karajan would immediately become the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. It was the beginning of an obsessive hate and contempt for Karajan that never left him until his death. He often refused to call Karajan by his name, calling him simply “Herr K”. Hitler’s opinion was that even if Furtwängler was infinitely better than Karajan as a conductor, it was necessary to keep Karajan “in reserve” since Furtwängler was “not politically trustworthy”.

Kristallnacht and the Anschluss

Furtwängler was very affected by the events of Kristallnacht. Berta Geissmar, who met him in Paris, described him as “greatly depressed”. Friedelind Wagner, who saw him also in Paris, wrote that he was a “very unhappy man”. Andrew Schulhof, who met him in Budapest said that “he had the impression that what he had done before for his Jewish friends had been lost”.

Furtwängler approved of the Anschluss that had occurred on 12 March 1938. But he quickly disagreed with the Nazi leaders’ decision to “annex Austrian culture” by abolishing independent cultural activity in Austria and subordinating it to Berlin. Just after the Anschluss, Furtwängler discovered that a huge Swastika flag was displayed in the hall of the Musikverein. He refused to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic “as long as the rag is visible”. The flag was finally removed.

Goebbels wanted to eliminate the Vienna Philharmonic and to convert the Vienna Opera and the Salzburg Festival into branches of the Berlin Opera and the Bayreuth Festival respectively. In addition, he wished to confiscate the largest musical collection in the world, belonging to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna and to move it to Berlin. Hitler’s goal was to deny that Austria had developed its own culture independently of Germany. Austrian musical circles asked Furtwängler, who was the honorary president of the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, to help them.

Furtwängler campaigned to convince Nazi leaders to abandon their plans. According to historian Fred K. Prieberg, he conducted concerts (often with the Vienna Philharmonic) in the presence of German leaders during this period in exchange for the conservation of the orchestra. He organized several concerts of Austrian music in Berlin and Vienna for Hitler, to highlight Austrian culture. The Nazi leadership, who wanted to take advantage of this situation, invited Furtwängler in 1938 to conduct Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg with the Vienna Philharmonic in Nürnberg for the Nazi party congress. Furtwängler accepted to conduct, as long as the performance was not during the party congress. Hitler eventually accepted Furtwängler’s conditions: the concert took place on 5 September and the political event was formally opened the following morning.This concert, along with one given in Berlin in 1942 for Hitler’s birthday, led to heavy criticism of Furtwängler after the war. However, Furtwängler had managed not to participate in the party congress. He had also succeeded in conserving the Vienna Philharmonic, and the musical collections of Vienna and the Vienna Opera, where he persuaded Hitler and Goebbels to agree to the appointment of Karl Böhm as artistic director. At the Vienna Philharmonic, as at the Berlin Philharmonic, Furtwängler succeeded in protecting ‘half-Jews’ or members with ‘non-aryan’ wives until the end of the war (these were exceptional cases in Germany during the Nazi period). However, in contrast to his experience with the Berlin Philharmonic, he could not save the lives of ‘full-blooded’ Jews: they were persecuted, with a number dying in concentration camps.

Goebbels was satisfied that Furtwängler had conducted the concerts in Vienna, Prague and Nürnberg, thinking that these concerts gave a “cultural” justification to the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia. During this period he said that Furtwängler was “willing to place himself at my disposal for any of my activities”, describing him as “an out-and-out chauvinist”. However, he regularly complained that Furtwängler was helping Jews and ‘half-Jews’, and his complaints continued during the war. Goebbels wrote in his diary that Furtwängler’s goal was to bypass Nazi cultural policy. For instance, Goebbels wrote that Furtwängler supported the Salzburg festival to counterbalance the Bayreuth festival, a keystone of the Nazi regime.

Furtwängler was very affected by the events of the 1930s. Fred K. Prieberg describes Furtwängler in 1939 as a “broken man”. The French government awarded him the Legion of Honour in 1939, which may support the theory that western diplomatic services knew Furtwängler was not a supporter of the Nazi regime. Hitler forbade news of the award to be spread in Germany.

World War II

During the war, Furtwängler tried to avoid conducting in occupied Europe. He said: “I will never play in a country such as France, which I am so much attached to, considering myself a ‘vanquisher’. I will conduct there again only when the country has been liberated”. He refused to go to France during its occupation, although the Nazis tried to force him to conduct there. Since he had said that he would conduct there only at the invitation of the French, Goebbels forced the French conductor Charles Munch to send him a personal invitation. But Munch wrote in small characters at the bottom of his letter “in agreement with the German occupation authorities.” Furtwängler declined the invitation. Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in a “work-break” concert at AEG in February 1941, organized by the Nazi “Strength Through Joy” program.

Furtwängler did conduct in Prague in November 1940 and March 1944. The 1940 program, chosen by Furtwängler, included Smetana’s Moldau. According to Prieberg, “This piece is part of the cycle in which the Czech master celebrated ‘Má vlast (My Country), and […] was intended to support his compatriots’ fight for the independence from Austrian domination When Furtwängler began with the ‘Moldau’ it was not a deliberate risk, but a statement of his stance towards the oppressed Czechs”. The 1944 concert marked the fifth anniversary of the German occupation and was the result of a deal between Furtwängler and Goebbels: Furtwängler did not want to perform in April for Hitler’s birthday in Berlin. He said to Goebbels in March (as he had in April 1943) that he was sick. Goebbels asked him to perform in Prague instead, where he conducted the Symphony No. 9 of Antonín Dvořák. He conducted in Oslo in 1943, where he helped the Jewish conductor Issay Dobrowen to flee to Sweden.

In April 1942, Furtwängler conducted a performance of Beethoven’s ninth symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic for Hitler’s birthday. At least the final minutes of the performance were filmed and can be seen on YouTube. At the end, Goebbels came to the front of the stage to shake Furtwängler’s hand. This concert led to heavy criticism of Furtwängler after the war. In fact, Furtwängler had planned several concerts in Vienna during this period to avoid this celebration. But after the defeat of the German army during the Battle of Moscow, Goebbels had decided to make a long speech on the eve of Hitler’s birthday to galvanize the German nation. The speech would be followed by Beethoven’s ninth symphony. Goebbels wanted Furtwängler to conduct the symphony by whatever means to give a transcendent dimension to the event. He called Furtwängler shortly before to ask him to agree to conduct the symphony but the latter refused arguing that he had no time to rehearse and that he had to perform several concerts in Vienna. But Goebbels forced the organizers in Vienna (by threatening them: some were physically assaulted by the Nazis) to cancel the concerts and ordered Furtwängler to return to Berlin In 1943 and 1944, Furtwängler provided false medical certificates in advance to be sure that such a situation would not happen again.

It is now known that Furtwängler continued to use his influence to help Jewish musicians and non-musicians escape the Third Reich. He managed to have Max Zweig, a nephew of conductor Fritz Zweig, released from Dachau concentration camp. Others, from an extensive list of Jews he helped, included Carl Flesch, Josef Krips and the composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Furtwängler refused to participate in the propaganda film Philharmoniker. Goebbels wanted Furtwängler to feature in it, but Furtwängler declined to take part. The film was finished in December 1943 showing many conductors connected with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, including Eugen Jochum, Karl Böhm, Hans Knappertsbusch, and Richard Strauss, but not Furtwängler. Goebbels also asked Furtwängler to direct the music in a film about Beethoven, again for propaganda purposes. They quarrelled violently about this project. Furtwängler told him “You are wrong, Herr Minister, if you think you can exploit Beethoven in a film.” Goebbels gave up his plans for the film.

In April 1944, Goebbels wrote:

Furtwängler has never been a National Socialist. Nor has he ever made any bones about it, which Jews and emigrants thought was sufficient to consider him as one of them, a key representative of so-called ‘inner emigration’. Furtwängler[‘s] stance towards us has not changed in the least.

Friedelind Wagner (an outspoken opponent of the Third Reich) reported a conversation with her mother Winifred Wagner during the war, to the effect that Hitler did not trust or like Furtwängler, and that Göring and Goebbels were upset with Furtwängler’s continuous support for his “undesirable friends”. Yet Hitler, in gratitude for Furtwängler’s refusal to leave Berlin even when it was being bombed, ordered Albert Speer to build a special air raid shelter for the conductor and his family. Furtwängler refused it, but the shelter was nevertheless built in the house against his will. Speer related that in December 1944 Furtwängler asked whether Germany had any chance of winning the war. Speer replied in the negative, and advised him to flee to Switzerland from possible Nazi retribution. In 1944, he was the only prominent German artist who refused to sign the brochure ‘We Stand and Fall with Adolf Hitler’.

Furtwängler’s name was included on the Gottbegnadeten list (“God-gifted List”) of September 1944, but was removed on 7 December 1944 because of his relationships with German resistance. Furtwängler had strong links to the German resistance which organized the 20 July plot. He stated during his denazification trial that he knew an attack was being organized against Hitler, although he did not participate in its organization. He knew Claus von Stauffenberg very well and his doctor, Johannes Ludwig Schmitt, who wrote him many false health prescriptions to bypass official requirements, was a member of the Kreisau Circle. Furtwängler’s concerts were sometimes chosen by the members of the German resistance as a meeting point. Rudolf Pechel, a member of the resistance group which organized the 20 July plot said to Furtwängler after the war: “In the circle of our resistance movement it was an accepted fact that you were the only one in the whole of our musical world who really resisted, and you were one of us.” Graf Kaunitz, also a member of that circle, stated: “In Furtwängler’s concerts we were one big family of the resistance.”

Grove Online states that Furtwängler was “within a few hours of being arrested” by the Gestapo when he fled to Switzerland, following a concert in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic on 28 January 1945. The Nazis had begun to crack down on German liberals. At the concert he conducted Brahms’s Second Symphony, which was recorded and is considered one of his greatest performances.

After World War II

In February 1946, Furtwängler met in Vienna a German Jew by the name of Curt Riess who had fled Germany in 1933. The latter was a musician and writer, he later wrote a book on Furtwängler. Riess was then a journalist and correspondent in Switzerland for American newspapers. He thought Furtwängler was a Nazi collaborator and objected to having Furtwängler directing in Switzerland in 1945. Furtwängler asked to meet him and when Riess had studied all the documents concerning Furtwängler, he completely changed his mind. Realizing that Furtwängler had never been a Nazi and had helped many people of Jewish origin, he became his “denazification advisor”. A long friendship ensued and Curt Riess spent the next two years doing everything to get Furtwängler whitewashed. As Roger Smithson writes at the conclusion of his article “Furtwängler, The Years of Silence (1945-1947)”: “Ultimately Furtwängler’s return to conducting was very largely the result of skill and stubbornness of Curt Riess. Furtwängler’s admirers owe him a great debt”.

Furtwängler initially wanted Curt Riess to write articles about him based on the many documents he had provided him because Curt Riess was a journalist. However, Curt Riess preferred to go himself to meet General Robert A. McClure who was in charge of the Furtwängler file. The general, after meeting Riess and having all the documents translated into English, admitted that no serious charge could be brought against Furtwängler and that they had made a mistake concerning the conductor who was “a very good man”. He asked Riess to tell Furtwängler not to speak to the press, so as not to give the impression that he was exerting pressure on the Allied forces. He said the case would be closed within weeks. Riess sent a telegram to Furtwängler to this effect, but the telegram took a long time to reach its destination and arrived too late.

In the meantime, Furtwängler had made a very serious mistake: he had gone to Berlin, which was occupied by the Soviets. The latter received him as a Head of State because they wanted to recover the one that Arsenyi Gouliga, the representative of the Soviet Union at the Furtwängler trial, called the “greatest conductor in the world” to lead a great cultural policy in Berlin. Precisely, the Soviets offered the post of director of the Berlin State Opera, which was in the Soviet zone, to Furtwängler. General Robert A. McClure was forced to pass Furtwängler by the normal denazification procedure. He explained to Curt Riess, by telephone, that otherwise it gave the impression that the Americans had ceded to the Soviets on the Furtwängler file. The American authorities knew that the conductor would necessarily be cleared by the denazification court and the Soviet authorities declared that this trial made no sense and was “ridiculous”. Thus, with the backdrop of the Cold War, Furtwängler, who absolutely wanted to recover the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra which was in the British occupation zone, was obliged to go through the denazification court

Furtwängler was thus required to submit to a process of denazification. The charges were very low. He was charged with having conducted two official Nazi concerts during the period 1933–1945. Furtwängler declared that for two concerts that had been “extorted” from him, he had avoided sixty. The first was for the Hitler Youth on 3 February 1938. It was presented to Furtwängler as a way to acquaint younger generations with classical music. According to Fred Prieberg: “when he looked at the audience he realized that this was more than just a concert for school kids in uniform; a whole collection of prominent political figures were sitting there as well and it was the last time he raised his baton for this purpose”.

The second concert was the performance of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg with the Vienna Philharmonic on 5 September 1938, on the evening before the Nazi congress in Nüremberg. Furtwängler had agreed to conduct this concert to help preserve the Vienna Philharmonic, and at his insistence the concert was not part of the congress.

He was charged for his honorary title of “Prussian State Counselor” (German: Preußischer Staatsrat) (he had resigned from this title in 1934, but the Nazis had refused his resignation) and with making an anti-semitic remark against the part-Jewish conductor Victor de Sabata (see below).The chair of the commission, Alex Vogel, known for being a communist, started the trial with the following statement:

“The investigations showed that Furtwängler had not been a member of any [Nazi] organization, that he tried to help people persecuted because of their race, and that he also avoided… formalities such as giving the Hitler salute.”[142]

The prosecution believed it had something more substantial because Hans von Benda, a former member of the Nazi Party who had been the artistic director of the Berlin Philharmonic during the Nazi period and had therefore been in constant contact with Furtwängler for many years, absolutely wanted to testify to accuse Furtwängler of anti-Semitism. He said he heard, during an argument with another German musician, that Furtwängler allegedly said: “a Jew like Sabata cannot play Brahms’ music” . This story soon became ridiculous: Furtwängler had played Brahms’ music with many Jewish musicians (especially those from his orchestra). This was either a mistake or a misunderstanding: Furtwängler probably had no anti-Semitic feelings towards Sabata who had been his friend. On the other hand, Hans von Benda was forced to admit that he was not directly present when Furtwängler allegedly spoke these words, and his testimony was therefore not taken seriously by the prosecution. The reason for Hans von Benda’s behavior was as follows: he had been dismissed from his post as artistic director of the Berlin Orchestra on 22 December 1939 for numerous serious professional misconduct. He had wished to take the opportunity of the lawsuit for take revenge on Furtwängler, considering him responsible for his dismissal because he would have supported Karajan, a version very strongly contested by Furtwängler and his wife. Moreover, historian Fred Prieberg has proved that, on the contrary, Hans von Benda had never ceased to send information to the Nazis (to denounce it) proving that Furtwängler was helping Jews and opposing their policies.

Two of the main people who prepared Furtwängler’s defense for his denazification trial were two German Jews who had to flee the Nazi regime: his secretary Berta Geissmar and Curt Riess. The two had very different backgrounds. Berta Geissmar knew Furtwängler personally and had witnessed everything he did at the start of the Nazi period; she left Germany in 1936 but returned from exile. Curt Riess didn’t know Furtwängler at all and initially had a very negative outlook on the conductor. Geissmar had collected hundreds of files to prepare the conductor’s defense, files which contained a list of over 80 Jewish and non-Jewish people who had claimed to have been helped or saved by him. This list was not exhaustive, but it concerned cases where Geissmar had managed to find indisputable concrete evidence. Among the many people involved were Communists, Social Democrats, as well as former Nazis whom the regime had turned against. Berta Geissmar had forwarded the documents to General Robert A. McClure in charge of the Furtwängler trial, but the documents had mysteriously disappeared in Berlin, when they were to be handed over to the general of the American zone of occupation. Curt Riess also did not find these documents in the Washington archives. Furtwängler therefore found himself without a means of proving the help he had given to many people. However, three people of Jewish origin had made the trip to Berlin and certified on 17 December 1946, the second day of the trial, that Furtwängler had risked his life to protect them. One of them was Paul Heizberg, former opera director. The other two were members of the Philharmonic such as Hugo Strelitzer, who declared:

If I am alive today, I owe this to this great man. Furtwängler helped and protected a great number of Jewish musicians and this attitude shows a great deal of courage since he did it under the eyes of the Nazis, in Germany itself. History will be his judge.

As part of his closing remarks at his denazification trial, Furtwängler said:

I knew Germany was in a terrible crisis; I felt responsible for German music, and it was my task to survive this crisis, as much as I could. The concern that my art was misused for propaganda had to yield to the greater concern that German music be preserved, that music be given to the German people by its own musicians. These people, the compatriots of Bach and Beethoven, of Mozart and Schubert, still had to go on living under the control of a regime obsessed with total war. No one who did not live here himself in those days can possibly judge what it was like. Does Thomas Mann [who was critical of Furtwängler’s actions] really believe that in ‘the Germany of Himmler‘ one should not be permitted to play Beethoven? Could he not realize that people never needed more, never yearned more to hear Beethoven and his message of freedom and human love, than precisely these Germans, who had to live under Himmler’s terror? I do not regret having stayed with them.

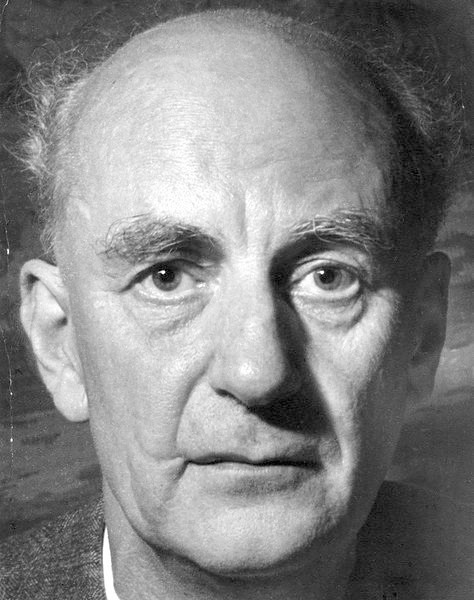

The prosecution itself acknowledging that no charge of anti-Semitism or sympathy for Nazi ideology could be brought against the conductor, Furtwängler was cleared on all the counts. Even after Furtwängler’s acquittal at the denazification trials, Mann still criticized him for continuing to conduct in Germany and for believing that art could be apolitical in a regime such as the Third Reich, which was so intent on using art as propaganda. In a drafted letter to the editor of Aufbau magazine, Mann praises Furtwängler for assisting Jewish musicians and as a “preeminent musician”, but ultimately presents him as a representative example of a fatal “lack of understanding and lack of desire to understand what had seized power in Germany”. Furtwängler’s tomb in Heidelberg

The violinist Yehudi Menuhin was, with Arnold Schoenberg, Bronisław Huberman, and Nathan Milstein, among the Jewish musicians who had a positive view of Furtwängler. In February 1946, he sent a wire to General Robert A. McClure in February 1946:

Unless you have secret incriminating evidence against Furtwängler supporting your accusation that he was a tool of Nazi Party, I beg to take violent issue with your decision to ban him. The man never was a Party member. Upon numerous occasions, he risked his own safety and reputation to protect friends and colleagues. Do not believe that the fact of remaining in one’s own country is alone sufficient to condemn a man. On the contrary, as a military man, you would know that remaining at one’s post often requires greater courage than running away. He saved, and for that we are deeply his debtors, the best part of his own German culture… I believe it patently unjust and most cowardly for us to make of Furtwängler a scapegoat for our own crimes.

In 1949 Furtwängler accepted the position of principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. However the orchestra was forced to rescind the offer under the threat of a boycott from several prominent musicians including Arturo Toscanini, George Szell, Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Rubinstein, Isaac Stern, and Alexander Brailowsky.

According to a New York Times report, Horowitz said that he “was prepared to forgive the small fry who had no alternative but to remain and work in Germany.” But Furtwängler “was out of the country on several occasions and could have elected to keep out”. Rubinstein likewise wrote in a telegram, “Had Furtwängler been firm in his democratic convictions he would have left Germany”. Yehudi Menuhin was upset with this boycott, declaring that some of the main organizers had admitted to him that they had organized it only to eliminate Furtwängler’s presence in North America.

Wilhelm Furtwängler died on 30 November 1954 of pneumonia, in Baden-Baden. He was buried in Heidelberg cemetery, the Bergfriedhof, in his mother’s vault. A large number of personalities from the artistic and political world were present, including Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

After Furtwängler’s death, the Jewish writer and theater director Ernst Lothar said:

He was totally German and he remained so, despite the attacks. This is why he did not leave his defiled country, which was later counted to him as a stain by those who did not know him well enough. But he did not stay with Hitler and Himmler, but with Beethoven and Brahms.

At the end of his life, Yehudi Menuhin said of Furtwängler, “It was his greatness that attracted hatred”.

Conducting style

Furtwängler had a unique philosophy of music. He saw symphonic music as creations of nature that could only be realised subjectively into sound. Neville Cardus wrote in the Manchester Guardian in 1954 of Furtwängler’s conducting style: “He did not regard the printed notes of the score as a final statement, but rather as so many symbols of an imaginative conception, ever changing and always to be felt and realised subjectively…” And the conductor Henry Lewis: “I admire Furtwängler for his originality and honesty. He liberated himself from slavery to the score; he realized that notes printed in the score, are nothing but SYMBOLS. The score is neither the essence nor the spirit of the music. Furtwängler had this very rare and great gift of going beyond the printed score and showing what music really was.”

Many commentators and critics regard him as the greatest conductor in history. In his book on the symphonies of Johannes Brahms, musicologist Walter Frisch writes that Furtwängler’s recordings show him to be “the finest Brahms conductor of his generation, perhaps of all time”, demonstrating “at once a greater attention to detail and to Brahms’ markings than his contemporaries and at the same time a larger sense of rhythmic-temporal flow that is never deflected by the individual nuances. He has an ability not only to respect, but to make musical sense of, dynamic markings and the indications of crescendo and diminuendo. What comes through amply… is the rare combination of a conductor who understands both sound and structure.” He notes Vladimir Ashkenazy who says that his sound “is never rough. It’s very weighty but at the same time is never heavy. In his fortissimo you always feel every voice…. I have never heard so beautiful a fortissimo in an orchestra”, and Daniel Barenboim says he “had a subtlety of tone color that was extremely rare. His sound was always ’rounded,’ and incomparably more interesting than that of the great German conductors of his generation.”

On the other hand, the critic David Hurwitz, a spokesman for modern literalism and precision, sharply criticizes what he terms “the Furtwängler wackos” who “will forgive him virtually any lapse, no matter how severe”, and characterizes the conductor himself as “occasionally incandescent but criminally sloppy”. Unlike conductors such as Carlos Kleiber or Sergiu Celibidache, Furtwängler did not try to reach the perfection in details, and the number of rehearsals with him was small. He said:

I am told that the more you rehearse, the better you play. This is wrong. We often try to reduce the unforeseen to a controllable level, to prevent a sudden impulse that escapes our ability to control, yet also responds to an obscure desire. Let’s allow improvisation to have its place and play its role. I think that the true interpreter is the one who improvises. We have mechanized the art of conducting to an awful degree, in the quest of perfection rather than of dream […] As soon as rubato is obtained and calculated scientifically, it ceases to be true. Music making is something else than searching to achieve an accomplishment. But striving to attain it is beautiful. Some of Michelangelo‘s sculptures are perfect, others are just outlined and the latter ones move me more than the first perfect ones because here I find the essence of desire, of the wakening dream. That’s what really moves me: fixing without freezing in cement, allowing chance its opportunity.

His style is often contrasted with that of his contemporary Arturo Toscanini. He walked out of a Toscanini concert once, calling him “a mere time-beater!”. Unlike Toscanini, Furtwängler sought a weighty, less rhythmically strict, more bass-oriented orchestral sound, with a more conspicuous use of tempo changes not indicated in the printed score.[174] Instead of perfection in details, Furtwängler was looking for the spiritual in art. Sergiu Celibidache explained,

Everybody was influenced at the time by Arturo Toscanini – it was easy to understand what he was trying to do: you didn’t need any reference to spiritual dimension. There was a certain order in the way the music was presented. With Toscanini I never felt anything spiritual. With Furtwängler on the other hand, I understood that there I was confronted by something completely different: metaphysics, transcendence, the relationship between sounds and sonorities […] Furtwängler was not only a musician, he was a creator […] Furtwängler had the ear for it: not the physical ear, but the spiritual ear that captures these parallel movements.

Furtwängler’s art of conducting is considered as the synthesis and the peak of the so-called “Germanic school of conducting”. This “school” was initiated by Richard Wagner. Unlike Mendelssohn‘s conducting style, which was “characterized by quick, even tempos and imbued with what many people regarded as model logic and precision Wagner’s way was broad, hyper-romantic and embraced the idea of tempo modulation”. Wagner considered an interpretation as a re-creation and put more emphasis on the phrase than on the measure. The fact that the tempo was changing was not something new; Beethoven himself interpreted his own music with a lot of freedom. Beethoven wrote: “my tempi are valid only for the first bars, as feeling and expression must have their own tempo”, and “why do they annoy me by asking for my tempi? Either they are good musicians and ought to know how to play my music, or they are bad musicians and in that case my indications would be of no avail”. Beethoven’s disciples, such as Anton Schindler, testified that the composer varied the tempo when he conducted his works. Wagner’s tradition was followed by the first two permanent conductors of the Berlin Philharmonic. Hans von Bülow highlighted more the unitary structure of symphonic works, while Arthur Nikisch stressed the magnificence of tone. The styles of these two conductors were synthesized by Furtwängler

In Munich (1907-1909), Furtwängler studied with Felix Mottl, a disciple of Wagner. He considered Arthur Nikisch as his model. According to John Ardoin, Wagner’s subjective style of conducting led to Furtwängler and Mendelssohn’s objective style of conducting led to Toscanini.

Furtwängler’s art was deeply influenced by the great Jewish music theorist Heinrich Schenker with whom he worked between 1920 and Schenker’s death in 1935. Schenker was the founder of Schenkerian analysis, which emphasized underlying long-range harmonic tensions and resolutions in a piece of music. Furtwängler read Schenker’s famous monograph on Beethoven’s Ninth symphony in 1911, subsequently trying to find and read all his books Furtwängler met Schenker in 1920, and they continuously worked together on the repertoire which Furtwängler conducted. Schenker never secured an academic position in Austria and Germany, in spite of Furtwängler’s efforts to support him. Schenker depended on several patrons including Furtwängler. Furtwängler’s second wife certified much later that Schenker had an immense influence on her husband. Schenker considered Furtwängler as the greatest conductor in the world and as the “only conductor who truly understood Beethoven”.

Furtwängler’s recordings are characterized by an “extraordinary sound wealth “, special emphasis being placed on cellos, double basses, percussion and woodwind instruments. According to Furtwängler, he learned how to obtain this kind of sound from Arthur Nikisch. This richness of sound is partly due to his “vague” beat, often called a “fluid beat”. This fluid beat created slight gaps between the sounds made by the musicians, allowing listeners to distinguish all the instruments in the orchestra, even in tutti sections. Vladimir Ashkenazy once said: “I never heard such beautiful fortissimi as Furtwängler’s.” According to Yehudi Menuhin, Furtwängler’s fluid beat was more difficult but superior than Toscanini’s very precise beat. Unlike Otto Klemperer, Furtwängler did not try to suppress emotion in performance, instead giving a hyper romantic aspect to his interpretations. The emotional intensity of his World War II recordings is particularly famous. Conductor and pianist Christoph Eschenbach has said of Furtwängler that he was a “formidable magician, a man capable of setting an entire ensemble of musicians on fire, sending them into a state of ecstasy”. Furtwängler desired to retain an element of improvisation and of the unexpected in his concerts, each interpretation being conceived as a re-creation. However, melodic line as well as the global unity were never lost with Furtwängler, even in the most dramatic interpretations, partly due to the influence of Heinrich Schenker and to the fact that Furtwängler was a composer and had studied composition during his whole life.

Furtwängler was famous for his exceptional inarticulacy when speaking about music. His pupil Sergiu Celibidache remembered that the best he could say was, “Well, just listen” (to the music). Carl Brinitzer from the German BBC service tried to interview him, and thought he had an imbecile before him. A live recording of a rehearsal with a Stockholm orchestra documents hardly anything intelligible, only hums and mumbling. On the other hand, a collection of his essays, On Music, reveals deep thought.

Influence

One of Furtwängler’s protégés was the pianist prodigy Karlrobert Kreiten who was killed by the Nazis in 1943 because he had criticized Hitler. He was an important influence on the pianist/conductor Daniel Barenboim, of whom Furtwängler’s widow, Elisabeth Furtwängler, said, “Er furtwänglert” (“He furtwänglers”). Barenboim has conducted a recording of Furtwängler’s 2nd Symphony, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Other conductors known to speak admiringly of Furtwängler include Valery Gergiev, Claudio Abbado, Carlos Kleiber, Carlo Maria Giulini, Simon Rattle, Sergiu Celibidache, Otto Klemperer, Karl Böhm, Bruno Walter, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Christoph Eschenbach, Alexander Frey, Philippe Herreweghe, Eugen Jochum, Zubin Mehta, Ernest Ansermet, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Bernard Haitink, Rafael Kubelík, Gustavo Dudamel, Jascha Horenstein (who had worked as an assistant to Furtwängler in Berlin during the 1920s), Kurt Masur and Christian Thielemann. For instance, Carlos Kleiber thought that “nobody could equal Furtwängler”. George Szell, whose precise musicianship was in many ways antithetical to Furtwängler’s, always kept a picture of Furtwängler in his dressing room. Even Arturo Toscanini, usually regarded as Furtwängler’s complete antithesis (and sharply critical of Furtwängler on political grounds), once said – when asked to name the World’s greatest conductor apart from himself – “Furtwängler!”. Herbert von Karajan, who in his early years was Furtwängler’s rival, maintained throughout his life that Furtwängler was one of the great influences on his music making, even though his cool, objective, modern style had little in common with Furtwängler’s white-hot Romanticism. Karajan said:

He certainly had an enormous influence on me […] I remember that when I was Generalmusikdirektor in Aachen, a friend invited me to a concert that Furtwängler gave in Cologne […] Furtwängler’s performance of the Schumann’s Fourth, which I didn’t know at the time, opened up a new world for me. I was deeply impressed. I didn’t want to forget this concert, so I immediately returned to Aachen.

Furtwängler is the greatest of all […]; Admittedly, one can sometimes dispute his choices, his options, but enthusiasm almost always prevails, especially in Beethoven. He is the musician who had the greatest influence on my artistic education.[202]

Furtwängler’s performances of Beethoven, Wagner, Bruckner, and Brahms remain important reference points today, as do his interpretations of other works such as Haydn’s 88th Symphony, Schubert’s Ninth Symphony, and Schumann’s Fourth Symphony. He was also a champion of modern music, notably the works of Paul Hindemith and Arnold Schoenberg and conducted the World premiere of Sergei Prokofiev‘s Fifth Piano Concerto (with the composer at the piano) on 31 October 1932 as well as performances of Béla Bartók‘s Concerto for Orchestra.

The musicians who have expressed the highest opinion about Furtwängler are some of the most prominent ones of the 20th century such as Arnold Schönberg, Paul Hindemith, or Arthur Honegger. Soloists such as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Yehudi Menuhin Pablo Casals, Claudio Arrau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf who have played music with almost all the major conductors of the 20th century have clearly declared upon several occasions that, for them, Furtwängler was the most important one. John Ardoin has reported the following discussion he has had with Maria Callas in August 1968 after having listened to Beethoven’s Eight with the Cleveland orchestra conducted by George Szell:

“Well”, she sighed, “you see what we have been reduced to. We are now in a time when a Szell is considered a master. How small he was next to Furtwängler.” Reeling this disbelief — not at her verdict, with which I agreed, but from the unvarnished acuteness of it — I stammered, “But how do you know Furtwängler? You never sang with him.” “How do you think?” she stared at me with equal disbelief. “He started his career after the war in Italy [in 1947]. I heard dozens of his concerts there. To me, he was Beethoven.”

Notable recordings

There are a huge number of Furtwängler recordings currently available, mostly live. Many of these were made during World War II using experimental tape technology. After the war they were confiscated by the Soviet Union for decades, and have only recently become widely available, often on multiple legitimate and illegitimate labels. In spite of their limitations, the recordings from this era are widely admired by Furtwängler devotees.

This is only a small selection of some of Furtwängler’s most famed recordings. For more information, see his discography and list of currently available recordings. The French Wilhelm Furtwängler Society also has a list of recommended recordings.

- Johann Sebastian Bach, St Matthew Passion (first half only), live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1952 (SWF)

- Bartók, Violin Concerto No. 2, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1953 (EMI)

- Beethoven, Third Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, December 1944 (Music and Arts, Preiser, Tahra)

- Beethoven, Third Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1952 (Tahra)

- Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, June 1943 (Classica d’Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Enterprise, Music and Arts, Opus Kura, Tahra)

- Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, May 1954 (Tahra)

- Beethoven, Sixth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, March 1944 (Tahra)

- Beethoven, Seventh Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1943 (Classica d’Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts, Opus Kura)

- Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, March 1942 with Tilla Briem, Elisabeth Höngen, Peter Anders, Rudolf Watzke, and the Bruno Kittel Choir (Classica d’Oro, Music and Arts, Opus Kura, Tahra, SWF)

- Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance at the 29 July 1951 re-opening of Bayreuther Festspiele (not to be confused with EMI’s release) with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen, Hans Hopf and Otto Edelmann. (Orfeo D’or, 2008).

- Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, ostensibly a live performance at the 29 July 1951 re-opening of Bayreuther Festspiele but purported by the President of the Wilhelm Furtwängler Society of America to actually be dress rehearsal takes edited by EMI into one recording, all performed prior to the actual public performance. (EMI, 1955).[220]

- Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance at the 1954 Lucerne Festival with the London Philharmonia, Lucerne Festival Choir, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elsa Cavelti, Ernst Haefliger and Otto Edelmann (Music and Arts, Tahra).

- Beethoven, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, 1947 (Testament)

- Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 5, studio recording with Edwin Fischer and with the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1951 (Naxos)

- Beethoven, Fidelio, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Kirsten Flagstad, Anton Dermota, Julius Patzak, Paul Schoeffler, Josef Greindl, and Hans Braun, August 1950 (Opus Kura)

- Beethoven, Fidelio, both live and studio recordings, with Martha Mödl, his preferred soprano, in the title role, and Wolfgang Windgassen, Otto Edelmann, Gottlob Frick, Sena Jurinac, Rudolf Schock, Alfred Poell, Alwin Hendriks, Franz Bierbach, and the Vienna Philharmonic.

- Brahms, First Symphony, live performance with the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg, October 1951 (Music and Arts, Tahra).

- Brahms, Second Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, January 1945 (Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts)

- Brahms, Third Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1949 (EMI).

- Brahms, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1943 (Tahra, SWF)

- Brahms, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1948 (EMI)

- Brahms, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, 1949 (Tahra, Naxos)

- Brahms, Piano Concerto No. 2, live performance with Edwin Fischer and with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942 (Testament)

- Bruckner, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1941 (WFCJ)

- Bruckner, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1942 (Classica d’Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts, Testament).

- Bruckner, Sixth Symphony (the first movement is missing), live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, November 1943 (Music and Arts)

- Bruckner, Seventh Symphony (adagio only), live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, April 1942 (Tahra).

- Bruckner, Eighth Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, October 1944 (Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts)

- Bruckner, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1944 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Franck, Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1945 (SWF)

- Furtwängler, Second Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, February 1953 (Orfeo)

- Gluck, Alceste Ouverture, studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1954 (SWF)

- Haendel, Concerto Grosso Opus 6 No. 10, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, February 1944 (Melodiya)

- Haendel, Concerto Grosso Opus 6 No. 10, live performance with the Teatro Colón Orchester, 1950 (Disques Refrain)

- Haydn, 88th Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 5 December 1951 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Hindemith, Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 16 September 1947 (Deutsche Grammophon, Urania)

- Mahler, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, live performance with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Vienna Philharmonic, 1951 (Orfeo)

- Mahler, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, studio recording with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1952 (Naxos, EMI)

- Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1952 (Naxos, EMI)

- Mozart, Don Giovanni, the 1950, 1953 and 1954 Salzburg Festival recordings (in live performance). These have been made available on several labels, but mostly EMI. A videotaped performance of Don Giovanni is also available, featuring Cesare Siepi, Otto Edelmann, Lisa Della Casa, Elisabeth Grümmer, and Anton Dermota.

- Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, a live performance from 27 August 1949, featuring Walther Ludwig, Irmgard Seefried, Wilma Lipp, Gertrud Grob-Prandl, Ernst Haefliger, Hermann Uhde, and Josef Greindl.

- Schubert, Eighth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1944 (SWF)

- Schubert. Ninth Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1951 (Deutsche Grammophon). The first movement is a supreme example of Furtwaengler’s style. Note the sharp accelerandi at the end of the introduction and the middle of the recapitulation.

- Schubert, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942 (Deutsche Grammophon, Magic Master, Music and Arts, Opus Kura)

- Schubert, Die Zauberharfe Overture, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, September 1953 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Schumann, Fourth Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon, May 1953 (Deutsche Grammophon).

- Sibelius, En saga, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, February 1943 (SWF)

- Tchaikovsky, Fourth Symphony, studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1951 (Tahra)

- Tchaikovsky, Sixth Symphony Pathétique, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, HMV, 1938 (EMI, Naxos).[227]

- Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, studio recording with Flagstad, HMV, June 1952 (EMI, Naxos).[228]

- Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen, 1950 (live recording from La Scala in Milan with Kirsten Flagstad)

- Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen with Wolfgang Windgassen, Ludwig Suthaus, and Martha Mödl, 1953 (EMI) (recorded live in the RAI (Radiotelevisione Italiana) studios).

- Wagner, Die Walküre, his last recording in 1954. EMI planned to record “Der Ring des Nibelungen” in the studio under Furtwängler, but he only finished this work shortly before his death. The cast includes Martha Mödl (Brünnhilde), Leonie Rysanek (Sieglinde), Ludwig Suthaus (Siegmund), Gottlob Frick (Hunding), and Ferdinand Frantz (Wotan).

Notable premieres

- Bartók, First Piano Concerto, the composer as soloist, Theater Orchestra, Frankfurt, 1 July 1927

- Schoenberg, Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Berlin, 2 December 1928

- Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No. 5, the composer as soloist, Berlin Philharmonic, 31 October 1932

- Hindemith, suite from Mathis der Maler, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Berlin, 11 March 1934

- Richard Strauss, Four Last Songs, Kirsten Flagstad as soloist, Philharmonia Orchestra, London, 22 May 1950

Notable compositions

Orchestral

Early works

- Overture in E♭ Major, Op. 3 (1899)

- Symphony in D major (1st movement: Allegro) (1902)

- Symphony in B minor (Largo movement) (1908; the principal theme of this work was used as the leading theme of the 1st movement of the Symphony No. 1, in the same key)

Later works

- Symphonic Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1937, rev. 1952-54)

- Symphony No. 1 in B minor (1941)

- Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1947)

- Symphony No. 3 in C♯ minor (1954)

Chamber music

- Piano Quintet (for two violins, viola, cello, and piano) in C major (1935)

- Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor (1935)

- Violin Sonata No. 2 in D major (1939)

Choral

(all early works)

- Schwindet ihr dunklen Wölbungen droben (Chorus of Spirits, from Goethe’s Faust) (1901–1902)

- Religöser Hymnus (1903)

- Te Deum for Choir and Orchestra (1902–1906) (rev. 1909) (first performed 1910)

In popular culture

- British playwright Ronald Harwood‘s play Taking Sides (1995), set in 1946 in the American zone of occupied Berlin, is about U.S. accusations against Furtwängler of having served the Nazi regime. In 2001 the play was made into a motion picture directed by István Szabó and starring Harvey Keitel and featuring Stellan Skarsgård in the role of Furtwängler.[229]

Furtwängler, Edwin Fischer most lively: Brahms Piano Concerto No.2 live 1942.Special transfer Brahms Piano Concerto No.2 B Flat Major, Furtwängler, Berlin Philharmonic & Edwin Fischer 9th November 1942 live. This is one of the most famous of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s war time recordings, and certainly a reference for the Brahms concerto.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Jbzf-n4LqQ