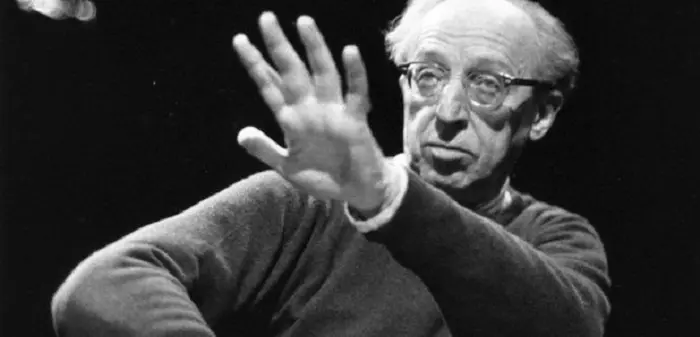

Aaron Copland (Brooklyn (New York), 14 november 1900 – Peekskill, 2 december 1990) was een Amerikaanse componist, muziekpedagoog, dirigent en pianist. Copland was een zoon van een joods echtpaar, dat uit Litouwen respectievelijk Polen gemigreerd was. Hij wordt als belangrijkste vertegenwoordiger van de zogenoemde Amerikaanse modernen beschouwd, die een voorliefde voor theatermuziek hadden. In de laatste jaren van zijn leven, waarin hij nauwelijks componeerde, werd hij als de ‘grand old man’ van de Amerikaanse muziek gezien. De componist en dirigent Leonard Bernstein heeft zich erg voor de muziek van Copland ingezet.

Het bekendste werk van Copland is zonder meer zijn Fanfare for the Common Man, voor koperblazers en slagwerk uit 1942, dat hij later opnam in zijn derde symfonie. Later werd de Fanfare zelfs bewerkt door de Britse popgroep Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Voor het werk Appalachian Spring werd hij in 1945 met de Pulitzerprijs voor muziek onderscheiden. In hetzelfde jaar kreeg hij ook nog de New York Music Critics’ Circle Award en in 1950 de begerenswaardige Academy Award voor de muziek voor de film The Heiress.

Oude en nieuwe wereld

Coplands vader had tijdens een verblijf in Engeland, voordat hij naar de Verenigde Staten emigreerde, de Engelse naam Copland aangenomen, zijn oorspronkelijke naam was Kaplan. Aaron groeide als jongste van het gezin op boven de winkel van vader Copland, een rotsvaste Democraat. Zijn moeder bracht het muzikale element in de familie. Alle kinderen kregen muziekles en werden frequent aan muziek blootgesteld, vaak op joodse bruiloften en tussen de schuifdeuren. Op elfjarige leeftijd schreef Aaron Copland zijn eerste compositie, zeven maten van een opera geheten Zenatello.

Aaron kreeg al op dertienjarige leeftijd pianoles van Victor Wittgenstein, Leopold Wolfsohn en Clarence Adler. Toen hij vijftien jaar was besloot hij, na een concert van de Poolse componist en pianovirtuoos Ignacy Jan Paderewski, dat hij ook componist wilde worden.

Na vergeefse pogingen om zijn muziekstudie met een schriftelijke cursus te vervolmaken ging hij lessen volgen bij Rubin Goldmark, een conservatieve harmonie-, theorie– en contrapuntleraar. Later zou hij gelukkig zijn met de saaie maar degelijke opleiding die hij gekregen had.

Tussen zijn zeventiende en zijn eenentwintigste schreef Copland een aantal nog onvoldragen pianocomposities en liederen. Zijn vader wilde dat hij een fatsoenlijke studie zou volgen, maar zijn moeder stelde hem in de gelegenheid in Parijs muziek te gaan studeren. Hij zou er drie jaar blijven, eerst als leerling van Paul Vidal, daarna van de beroemde muziekpedagoge Nadia Boulanger aan de Conservatoire américain de Fontainebleau in het koninklijk paleis. Boulanger zag meteen dat de schuchtere Amerikaan talent had. En in de lente van 1924 stelde ze hem voor aan de mecenas Sergej Koesevitski.

In de zomermaanden van 1924 en 1925 kwam hij in Berlijn, Salzburg en Wenen met de Europese avant-garde in contact. In 1925 en 1926 kreeg hij een studiebeurs van de Guggenheim Foundation. Daarom kon hij ook in deze jaren tijdens de zomer door Europa reizen. Met Roger Sessions (1896-1985) organiseerde hij een concertreeks met nieuwe muziek in New York, de Copland-Sessions Concerts (1928-1931).

Muziekbemiddelaar

Copland zette zich als muziekpedagoog, maar ook in publicaties en voordrachten hartstochtelijk in voor de verbreding van hedendaagse, vooral Amerikaanse muziek; vanaf 1924 was hij privéleraar en sinds 1925 recensent van het tijdschrift Modern Music; hij doceerde van 1927 tot 1937 aan de New School for Social Research in New York; van 1933 tot 1944 en 1951/1952 als professor aan de Harvard-universiteit in Cambridge (Massachusetts) alsook van 1940 tot 1965 aan Koesevitski’s Summer School van het Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood (een van zijn leerlingen daar was Julián Orbón). Zijn voordrachten werden de basis van veel gelezen publicaties zoals Our New Music (1941) en Music and Imagination, maar zij voerden ook tot talrijke optredens als uitvoerder en leider van gespreksconcerten in de televisie.

Als pedagoog en invloedrijke persoon (onder andere van 1939 tot 1951 president van de American Composers’ Alliance; van 1948 tot 1951 directeur van de League of Composers) steunde hij componisten zoals Leonard Bernstein, Carlos Chávez, Toru Takemitsu en David Del Tredici.

Jazz

Zijn grote interesse in jazz, die al tijdens zijn studie in Parijs was ontstaan, werd veroorzaakt doordat hij zijn best wilde doen om het publiek uit zijn composities onmiskenbaar te laten horen dat hij een Amerikaan was; precies zoals de door hem bewonderde Igor Stravinsky erin geslaagd was dat men uit zijn muziek kon horen, dat hij een Rus was. Jazzritmes en de harmonie van de blues vindt men terug in zijn vroege werken, zoals in het “Scherzo” van de Symfonie voor orgel en orkest (1924), de suite Music for the Theatre (1925) en het tweede deel “Essay in Jazz” uit het Concert voor piano en orkest.

Music for the Common Man (Muziek voor de gewone man)

Een reis naar Mexico in 1932 inspireerde hem tot het stuk El Salón México (1933-1936), voor orkest. In 1938 begon hij met Billy the Kid een serie folkloristisch geïnspireerde balletcomposities, die Coplands muziek bij een breed publiek bekend maakte. Daarna volgden Rodeo (1942) (ook al bewerkt door ELP), Appalachian Spring (1944) en Dance Panels (1959). Verder gebruikte Jerôme Robbins het voor Benny Goodman gecomponeerde Concert voor klarinet en orkest uit 1948 voor het ballet Pied Piper. Daarnaast componeerde Copland tussen 1939 en 1961 muziek voor acht films.

Fanfare for the Common Man is misschien het bekendste werk van Copland, geschreven in 1942 voor koperblazers en slagwerk op vraag van de dirigent Eugène Goossens van het Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Later werd het als openingstune van de Nationale Conventies van de Democratische partij gebruikt. De fanfare werd eveneens gebruikt als hoofdthema in het vierde deel van zijn Symfonie Nr. 3.

Van Coplands oeuvre wordt soms gedacht dat het vooral uit geleende muziek (b.v. folkloremuziek, jazzritmes etc.) bestaat; een oordeel, dat door anderen wordt tegengesproken. Het feit, dat vooral de symfonische suites naast deze danscomposities buiten de Verenigde Staten tot het standaardconcertrepertoire van de orkesten behoren, spreekt die eerste stelling tegen. Voorts werden deze volksmuziekmotieven niet zomaar overgenomen, maar meermalen bewerkt, de motieven vormden meestal slechts het basismateriaal. In andere werken, zoals in El Salón México, Danzón Cubano of de latere Three Latin American Sketches (1972) werd Latijns-Amerikaanse dansmuziek op dezelfde manier verwerkt; de muziek van het land van herkomst was basismateriaal, maar werd uiteindelijk ontegenzeggelijk muziek van Copland.

Academisme

In de jaren 1950 distantieerde de componist zich van de populaire tendenties van de jaren ervoor en sloot zich compositorisch aan bij de experimentele werken van de late jaren 1920, zoals het compromisloos dissonante Piano Variations (1930). Werken zoals het Pianokwartet (1950), de Pianofantasie (1954) en twee stukken voor het New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Connotations (1962) en Inscape (1967), zijn werken met de dodecafonie (twaalftoontechniek). Leonard Bernstein vatte dat op als een vertwijfelde poging om zich te kunnen aansluiten bij de Modernen met hun twaalftoonstechniek. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog zou het serialisme zijn zegetocht beginnen, dat immers gebaseerd was op het Modernisme van Arnold Schönberg en de zijnen. De jonge componisten namen geleidelijk afstand van Copland. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aaron_Copland

World Premiere of Aaron Copland’s Sonata for violin and piano Ruth Posselt, violin Aaron Copland, piano February 20, 1944 Recorded off the air from WNYC

THE CRITIC–COMPOSER Virgil Thomson famously declared, “Every town in America has two things — a five-and-dime and a Boulanger pupil.” He was talking about the famous French music teacher Nadia Boulanger, whose school at Fontainebleau Palace, just outside Paris, became a mecca for young composers from the United States.

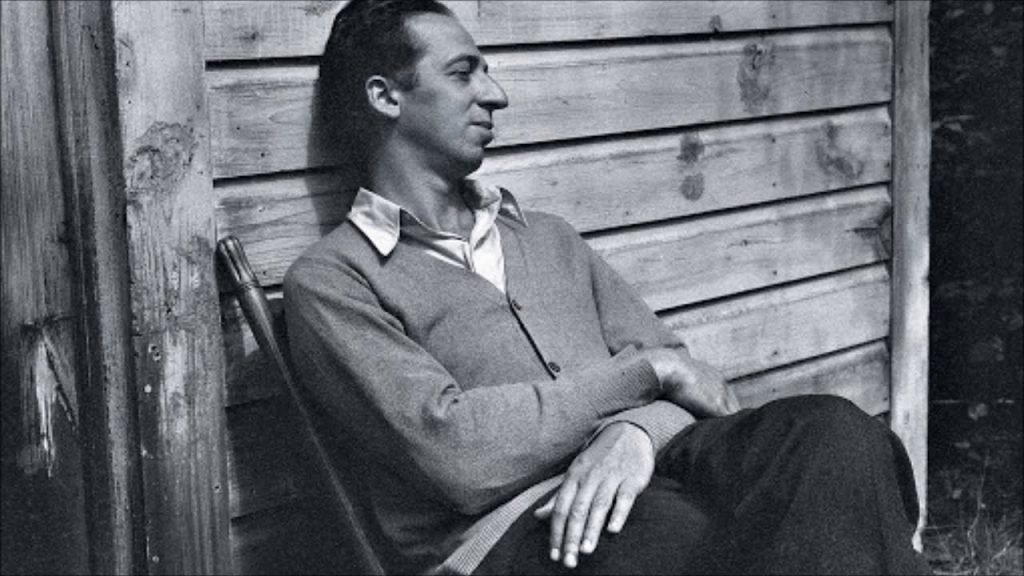

Boulanger was one of the defining forces of American music in the twentieth century. Many of her pupils went on to have impressive careers, but none more so than a twenty-one-year-old New Yorker who had started in music late but was determined to become a composer. His name was Aaron Copland.

Copland was the youngest of five children born into a family of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. (Originally Kaplan, Aaron’s father anglicized the family name en route to America.) Copland Senior put down roots in Brooklyn, where he owned a small department store; the family lived upstairs and helped to run the business.

The composer later recalled, with a kind of ironic pride, that his neighborhood was a drab place, adding: “I am filled with mild wonder each time I realize that a musician was born on that street.” Yet his mother played the piano and sang, and some of his siblings also took an amateur interest in music.

Copland might also have become an amateur musician, but at fifteen he attended a concert by the famous pianist Ignacy Paderewski. He decided then and there to become a composer, and backed up his ambition with a decisive course of action. He studied piano, harmony and theory with purposeful intensity, and developed a keen interest in the modern music coming out of Europe.

When he heard through a friend that a new school for American composers was being established in France, he pooled his money and stepped forward as the first student to enroll at Fountainebleau in 1921. He had no doubt that he wanted to spend a year in Europe — but he had qualms about learning composition from a woman. Nobody, to his knowledge, had ever done this before.

Copland soon found his misgivings groundless, and developed a deep admiration for Boulanger, an organist who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of music from Bach to Stravinsky. And the respect was mutual: she later recalled that she recognized his exceptional talent immediately. The young composer absorbed the exciting culture of Paris in the 1920s, the milieu in which such writers as Paul Bowles, Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway flourished.

One year in France became three, and Copland returned to the United States in 1924, well-versed in modern musical trends. Yet he returned to a nation whose musical life was very different from the America of today. There were, to be sure, a handful of American composers who had achieved a respectable level of success: Edward MacDowell, George Chadwick and Horatio Parker, among others. But the dream of writing a kind of classical music that was authentically American in style — in the same way that French music sounds French and German music sounds German — had proven elusive. America’s composers were too European in their sensibilities, and perhaps America itself wasn’t quite ready to embrace the idea.

Copland would become a leader in the generation that changed all that. But first, like every young artist, he wanted a big break — and the one he got couldn’t have been bigger. Boulanger helped make this happen: she introduced Copland to the esteemed Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who was about to assume the direction of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He asked the young composer to write a large-scale work for organ and orchestra, which Boulanger could perform on an upcoming tour to America.

Boulanger also approached Walter Damrosch, conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra, about the piece, and on January 25, 1925, Copland’s Symphony for Organ and Orchestra was premiered by the NYSO. A Boston performance under Koussevitzky followed in February. The three-movement composition, with its fluid harmonies and Stravinskian, irregular rhythms, received mixed reviews. Even Damrosch seemed uneasy about the work, famously remarking to his audience, “If a young man at the age of twenty-three can write a symphony like that, in five years he will be ready to commit murder.” (Copland later created an alternate version of the piece, without organ, calling it his Symphony No. 1.)

It could be argued that, like Dmitri Shostakovich, Copland had a ‘public style’ for his orchestral scores and a ‘personal style’ for chamber works.

Copland was now in the musical spotlight, and his goal of becoming a full-time composer of classical music (a profession that didn’t really exist in America at that time) lay within his grasp. Guggenheim fellowships and part-time teaching allowed him to live modestly in a New York apartment and work on his music. He banded together with other young composers — Roger Sessions, Roy Harris, Walter Piston and Virgil Thomson — who became collectively known as the “Commando Unit.” He became involved in the newly formed League of Composers. In his personal life he was openly homosexual, and he also took an interest in left-wing politics.

His association with Koussevitzky proved fruitful: the BSO’s flamboyant conductor led Copland’s jazzy and abrasive Piano Concerto, with the composer at the piano, in a 1927 concert that scandalized many Bostonians. And Copland’s star rose higher when, in 1929, his Dance Symphony won a prize in a music competition sponsored by RCA Victor.

With the arrival of the Great Depression, America’s musical landscape changed, and Copland adapted to the new circumstances. His left-leaning political convictions led him to question his own artistic values. And he came to feel that a new musical language — distinct from the brashly modernist idiom he had so successfully cultivated in the 1920s — was needed, in order to reach a wider audience. “I see no reason,” he wrote, “why composers any longer should write their music solely with the concert audience in mind. New listeners, such as the radio provides, may not be cultivated listeners, but at least they have few of the prejudices of the typical concert-goer.”

Several years after his sparsely pontillistic Piano Variations of 1930 (adapting the serial techniques of Arnold Schoenberg to his own purposes), Copland made a dramatic shift in style. His 1936 ballet El Salón México, inspired by folk melodies he heard on a trip, marks the beginning of this new aesthetic approach: transparent, melodic and unashamedly populist. More works in this vein followed, such as the ballets Billy The Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring, with its famous use of the Shaker hymn “Simple Gifts.” Copland also broadened his audience by composing for theatre, radio and film. His 1939 music for Of Mice and Men marked the beginning of his association with Hollywood.

Yet Copland was still, at heart, very much a composer for the concert hall. And when Koussevitzky approached him in 1944 to write a new symphony for the BSO, he began work on a piece that would marry his populist and classical inclinations. He worked slowly, well aware that the piece would be judged as the culmination of his career up to that point. “A forty-minute symphony is very different from a short work for a specific purpose,” he later told biographer Vivian Perlis. “It has to be planned very carefully and given enough time to evolve. http://www.listenmusicculture.com/mastery/copland-you-know