For a long time I have revered the warm and respectful friendship between two of Russia’s greatest composers: Sergei Rachmaninov and Nikolai Medtner. The support and encouragement that Rachmaninov offered to his friend and colleague during the periods of tormenting self-doubt were always reciprocated by Medtner, as witnessed by many letters. Unfortunately the latter never came close to attaining the same level of recognition as Rachmaninov, either during his lifetime or since. Rachmaninov recognized his gifts early enough, however, pronouncing Medtner the ‘greatest composer of our time’. The most sincere testament to this unique friendship is embodied in these two piano concertos, which the composers dedicated to one another.

Nikolai Medtner: Piano Concerto No. 2 Op. 50 in C minor

Unfairly described as ‘the poor man’s Rachmaninov’ or ‘Rachmaninov without the memorable tunes’ by certain Music-Neanderthals, Medtner never strayed from his ideals and disregarded the low-hanging fruits of popularity – a truly admirable and all too rare quality in an artist. As Sorabji wrote: ‘Like Sibelius, Medtner does not flout current fashions, he does not even deliberately ignore them, but so intent going his own individual way is he that he is simply unconscious of their very existence… he has made for himself, by the sheer strength of his own personality, that impregnable inner shrine and retreat that only the finest spirits either dare or can inhabit’. A case in point was the despair, shared by Rachmaninov, that Medtner felt regarding the modernist direction in which Schönberg and Stravinsky were leading classical music. Taking a Michelangeloesque ethos to heart, Medtner was convinced that the ideas he was putting down on paper already existed somewhere in one shape or another. They just needed to be captured by someone and given substance – a case of plagiarizing God, as it were. In the words of the Russian philosopher Ivan Ilyin: ‘Medtner’s music astonishes and delights…you may fancy that you have heard the melody before….But where, when, from whom, in childhood, in a dream, in delirium? You will scratch your head and strain your memory in vain: you have not heard it anywhere: in human ears it sounds for the first time…And yet it is as though you had long been waiting for it – waiting because you ‘knew’ it, not in sound, but in spirit. For the spiritual content of the melody is universal and primordial…it is as though age-long desires and strivings of our forebears were singing in us; or, as though the eternal melodies we had heard in heaven and preserved in this life as ‘strange and lovely yearnings’, were remembered at last and sung again – chaste and simple.’

Not exactly heaven-like, the C minor opening of his Second Piano Concerto (composed in France in 1926/27) makes it immediately clear that despite the dedication to Rachmaninov the piece is in no way a pastiche, but rather a tribute or ‘musical letter’ from an individual of equal stature. The first movement ‘Toccata’ is written in sonata form, of which Medtner was a true master: his teacher Taneyev frequently exclaimed that Medtner was ‘born with sonata form’. (This aptitude was one that I think Rachmaninov sometimes struggled to emulate, resulting in obsessive revisions.) As with Bach’s or many of Chopin’s compositions, it is almost impossible to add or take away a note (at least on purpose); when you play works of this kind you have a feeling that they are blessed with a perfect touch. Not a single note appears superfluous (a word Rachmaninov dreaded, yet used frequently when describing some of his own early works,). Like in Brahms or late Beethoven, such terms as ‘melody’ and ‘harmony’ are basically interchangeable and are all in aid of the form, Medtner’s Holy Grail. ‘Melody…should actually be viewed only as a form of the theme. Form…is harmony. Form without contents is nothing but a dead scheme’, Medtner wrote in his book The Muse and the Fashion (which Rachmaninov helped him publish).

After the concerto’s rather militant opening, where typical Medtnerian rhythms are immediately recognized (from the way rests and off-beat accents are distributed, reinforcing the pulsating nature of the phrases), one gets a good sense of the fatalistic character of the piece – in case one hasn’t already been hit on the head by the key of C minor. But soon, through the E flat major of the second subject (molto cantabile), an expansiveness and a penetrating lyricism of the kind that brings back memories of the great Russian landscapes (dear also to Rachmaninov) begin to resonate strongly, before accelerating and turning into hunting calls when a third subject is introduced in the piano, followed by strings (al rigore di tempo). Like Rachmaninov, Medtner was a great pianist, as shown by various recordings, and the massive cadenza in the first movement features some of Medtner’s most ambitious piano writing, elaborating all previously encountered ideas. What’s immediately noticeable is that, no matter how difficult the writing, the notes – and there are always many – lie extremely comfortably under the hands, and that each note is essential, always serving the development of thematic material.

The slow movement, Romance, is in A flat major and has a ternary form with a stormy, quasi- rhapsodic C sharp minor Agitato section. In structure, it is very similar to the second movement of Rachmaninov’s Fourth (in terms of its length and effect, however, Rachmaninov’s middle-section – even in its original version – is more of a melodramatic burp, when the grumpy and indiscreet sounds originating from the brass come up violently in waves.) The main theme begins in thirds and of particular interest is the phrase with the falling fifth (C – F), which starts in the piano and is continued by horn, clarinet, basses and first violins in succession. This interval recurs throughout the movement and is probably the main source of the warmth that radiates from it.

In the recapitulation, beautiful silky textures in the right hand complement the more velvety sounds coming from the main theme in the strings. The transition into the last movement is rather unusual; after the exultation of the climax, the trumpet, in a foreshadowing of the theme of the closing movement, announces a new interval (E – D). This is immediately taken up by the piano, which ends the movement with a jazzy flourish while the strings uphold a harmonic ambiguity, which is resolved into the dominant once the C sharp squeezes itself into a D. To my mind, the only other similarly magical moment appearing between movements is in the transition to the finale of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor Concerto’.

The exuberant (even by Medtner’s standards) final movement is a Divertimento-Rondo, exhibiting a wealth of references not only to previous movements (with the themes inverted, retrograded, augmented, modulated, intertwined and a lot of other fun things) but also to some of Rachmaninov’s works, including his piano concertos and songs . The middle section of the movement gives ample opportunities for chamber music between the piano and various solo instruments (in turns bassoon, clarinet, oboe and first violin) before a potent fugue-like section (sempre al rigore di tempo) eventually takes over. The second subject (L’istesso Tempo. Marciale) appears both in the exposition and recapitulation (just like it does in the finale of the original version of Rachmaninov’s Fourth.) This march includes a clever, typically Medtnerian rhythmic feature: the piano is in 3/4, countered by the orchestral accompaniment in 2/4. An accelerated version of the march makes up the majestic coda – presaged by a cascading cadenza – in which a triplet rhythm dominates in the piano while themes from previous movements are heard in the orchestra. You need a really good ear – or two – to discern exactly what is going on, however: the woodwind inverting the second subject of the first movement, and clarinets and first violins presenting augmentations of other themes from previous movements – while, simultaneously, entirely new material is being created. Making new stuff from old is something Medtner – and Rachmaninov – was exceptionally good at.

While many pianists of the past (including Horowitz, who unfortunately only recorded one short piece) huffed and puffed, expressing encouragement and support towards Medtner’s work, hardly anybody actually tackled Medtner seriously. Moiseiwitsch did include some Medtner in his programmes and Gilels recorded two works, but otherwise he remained largely under-performed and under-loved. In the present day things are looking up, however, with Demidenko, Milne, Berezovsky, and Hamelin doing pioneer work in resurrecting his music. Why this concerto is not performed more often nevertheless remains a mystery and is nothing short of scandalous: it offers everything a pianist, or even a conductor, can wish for.

Sergei Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 4 Op. 40 in G minor

As the work’s dedicatee, it is just more bad luck for Medtner that the Fourth Piano Concerto has turned out to be one of Rachmaninov’s least performed works. Apart from Michelangeli, none of the master pianists of the past championed this work like they did with his Third. Likewise the movie studios didn’t find enough of the tear-jerking potential of his Second in it (even though occasionally one can tell where some of John Williams’ ideas have sprung from). What’s worse, the concerto in its glorious original 1926 version is almost unheard of.

There are in fact three versions of the concerto in total. The original version of 1926 had an unsuccessful première in Philadelphia in 1927, with Rachmaninov immediately starting to make numerous cuts and amendments before publishing it in 1928. The critics had their ‘fun’ with it, for instance Pitts Sanborn in the New York Evening Telegram: The concerto in question is an interminable, loosely knit hodge-podge of this and that, all the way from Liszt to Puccini, from Chopin to Tchaikovsky. Even Mendelssohn enjoys a passing compliment. The orchestral scoring has the richness of nougat and the piano part glitters with innumerable stock trills and figurations. As music it is now weepily sentimental, now of an elfin prettiness, now swelling toward bombast in a fluent orotundity. It is neither futuristic music nor music of the future. Its past was a present in Continental capitals half a century ago. Taken by and large-and it is even longer than it is large-this work could fittingly be described as super-salon music. Mme. Cécile Chaminade might safely have perpetrated it on her third glass of vodka.

Others called it ‘long-winded, tiresome, unimportant, in places tawdry, amorphous and difficult to grasp on a single hearing…’ – adjectives very similar to those used in spiteful descriptions of many of Medtner’s works, which is somewhat ironic, given the dedication. Rachmaninov subsequently lost whatever was left of his confidence and withdrew the concerto until he attempted a final and most extensive revision in 1941 reducing the concerto from a total of 1016 to just 902 bars; most of the cuts are in the final movement. Unfortunately even this did not aid its popularity. It is my opinion regarding many of Rachmaninov’s revised works (e.g. the Second Piano Sonata and the Second Symphony), that he should have stuck to his guns as the original versions are usually superior, in terms of both form and emotional impact. The Fourth Piano Concerto is a case in point: in its original version a truly epic work and, as an added ‘bonus’, much more insanely difficult than the revised version. I find the revised version too truncated; it has lost its violent contrasts of musical ideas, particularly in the Finale, where the Dies Irae-tinged theme has been removed almost completely and the severe rhythmic abnormalities (often quoting or teasing Medtner) have largely been ironed out (probably resulting from conductors’ complaints!). The harmonies are less pungent in the revised finale, and Rachmaninov cuts out the return of the second subject, so that instead of an unstoppable, psychedelic coda – which requires such rhythmic precision that if you blink in the wrong place, everything immediately falls apart – he inserts one of his trade-mark ‘big tunes’ towards the end, a feature evidently intended as a crowd-pleaser, and also present in his overwhelmingly successful Second and Third Concertos.

The feeling of ‘bits’n pieces’ occasionally experienced during the concerto can partly be attributed to Rachmaninov’s sudden departure from his motherland. Rachmaninov, like Medtner, usually conceived compositions in their entirety: ‘I go for a long walk in the country. My eye catches the spark of light on fresh foliage after showers, my ears the rustling undertone of the woods. Or I watch the pale tints of the sky over the horizon after sun-down and they come – all voices at once.’ Unlike Medtner, however, he quickly yielded to adverse opinions and doubts would set in even before the ink was dry. There are indications that he may have begun working on the concerto in Ivanovka (his country retreat for divine inspiration south of Moscow) as early as 1914, before departing Russia for good in 1917. Had he not left, the concerto, probably in a somewhat different shape or form, might well have been premiered already in 1919. The eight years that followed his departure were instead spent away from composition: in order to support his wife and two daughters Rachmaninov was mainly occupied with touring. Towards the end of 1925 he took a sabbatical, however, working on the Fourth Concerto. Soon after he wrote to Medtner expressing his worries about its length, complaining that it would have to be performed on consecutive nights, like Wagner’s Ring. As always a true friend, Medtner disagreed wholeheartedly: considering the importance of the work, he was amazed at the ‘fewness of the pages’ and maintained that Rachmaninov didn’t suffer from fear of length but from fear of boredom. Another friend and colleague, the legendary pianist Josef Hofmann, also praised the concerto and hoped that, even if its frequent metric changes might make playing the piece with an orchestra difficult, this would not prove an obstacle to future performances. In spite of all this support and encouragement, the concerto remains a rare beast in concert halls, and the original 1926 version stays abandoned with the status of an obscure curiosity. https://www.yevgenysudbin.com/artist.php?view=prog&rid=515

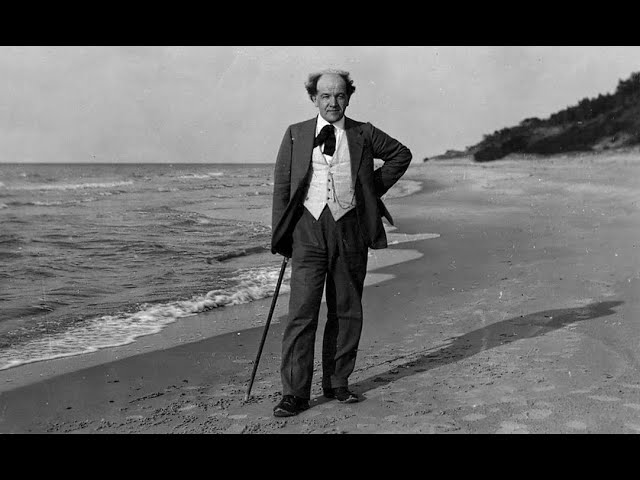

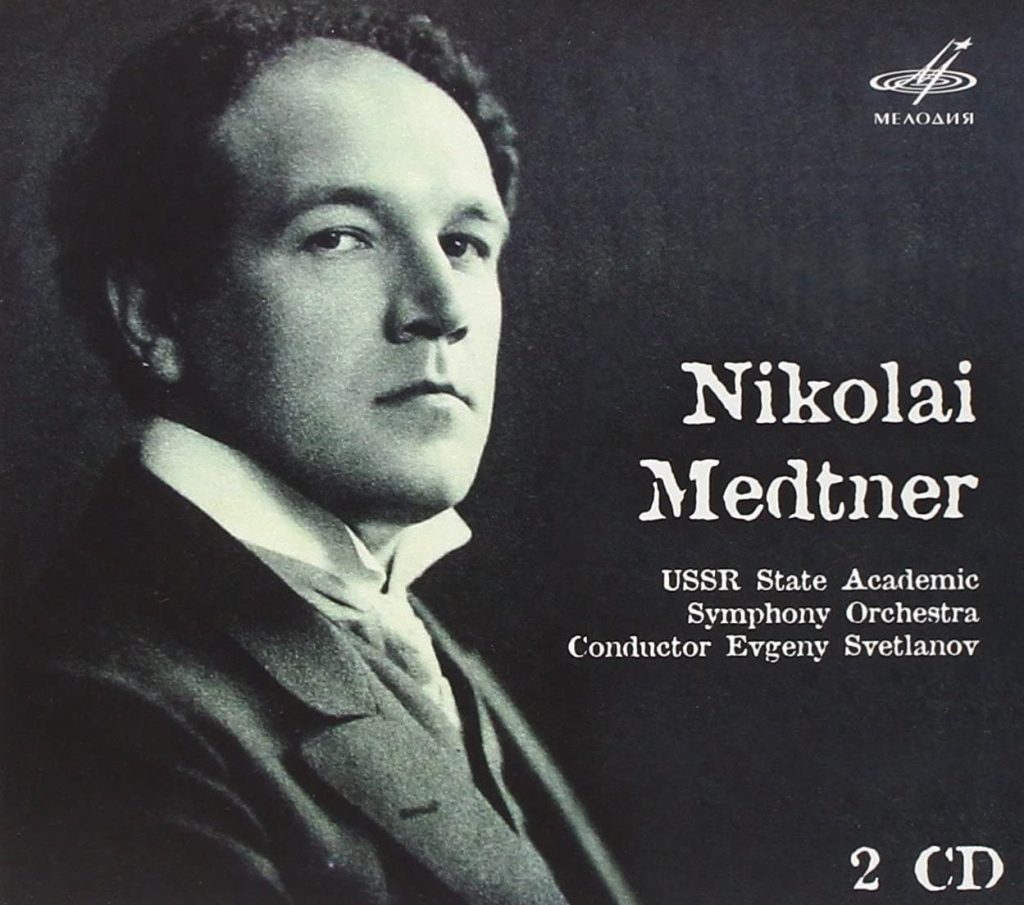

Medtner: 5 January 1880 [O.S. 24 December 1879] – 13 November 1951) was a Russian composer and pianist. After a period of comparative obscurity in the twenty-five years immediately after his death, he is now becoming recognized as one of the most significant Russian composers for the piano.

A younger contemporary of Sergei Rachmaninoff and Alexander Scriabin, he wrote a substantial number of compositions, all of which include the piano. His works include fourteen piano sonatas, three violin sonatas, three piano concerti, a piano quintet, two works for two pianos, many shorter piano pieces, a few shorter works for violin and piano, and 108 songs including two substantial works for vocalise. His 38 Skazki (generally known as “Fairy Tales” in English but more correctly translated as “Tales”) for piano solo contain some of his most original music.

Biography

The youngest of five children, Nikolai Medtner was born in Moscow on Christmas Eve 1879, according to the Julian calendar then in use in Russia. The Gregorian calendar, in use in the West at the time, and by which all dates are calculated today, gives his date of birth as 5 January 1880.

Medtner first took piano lessons from his mother until the age of ten. He also had lessons from his mother’s brother Fyodor Goedicke (the father of his more famous cousin Alexander Goedicke). Then he entered the Moscow Conservatory. He graduated in 1900 at the age of 20, taking the Anton Rubinstein prize, having studied under Pavel Pabst, Wassily Sapellnikoff, Vasily Safonov and Sergei Taneyev among others. Despite his conservative musical tastes, Medtner’s compositions and his pianism were highly regarded by his contemporaries. To the consternation of his family, but with the support of his former teacher Taneyev, he soon rejected a career as a performer and turned to composition, partly inspired by the intellectual challenge of Ludwig van Beethoven‘s late piano sonatas and string quartets. Among his students in this period was Alexander Vasilyevich Alexandrov.

During the years leading up to the 1917 Russian Revolution, Medtner lived at home with his parents. During this time Medtner fell in love with Anna Mikhaylovna Bratenskaya (1877–1965), a respected violinist and the young wife of his older brother Emil. Later, when World War I broke out, Emil was interned in Germany where he had been studying. He generously gave Anna the freedom to marry his brother. Medtner and Anna were married in 1918.

Unlike his friend Rachmaninoff, Medtner did not leave Russia until well after the Revolution. Rachmaninoff secured Medtner a tour of the United States and Canada in 1924; his recitals were often all-Medtner evenings consisting of sonatas interspersed with songs and shorter pieces. Medtner never adapted himself to the commercial aspects of touring and his concerts became infrequent. Esteemed in England, he and Anna settled in London in 1936, modestly teaching, playing and composing to a strict daily routine.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Medtner’s income from German publishers disappeared, and during this hardship ill-health became an increasing problem. His devoted pupil Edna Iles gave him shelter in Warwickshire where he completed his Third Piano Concerto, first performed in 1944.

In 1949 a Medtner Society was founded in London by His Highness Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar Bahadur, the Maharajah of Mysore (the princely state in southern India). The Maharajah was an honorary Fellow of Trinity College of Music, London, in 1945 and was the first president of the Philharmonia Concert Society, London. He founded the Medtner Society to record all of Medtner’s works. Medtner, already in declining health, recorded his three Piano Concertos and some sonatas, chamber music, numerous songs and shorter works before his death in London in 1951. In one of these recordings he partnered Benno Moiseiwitsch in his two-piano work entitled “Russian Round-Dance”, Op 58, No. 1; in another he accompanied Elisabeth Schwarzkopf in several of his lieder, including The Muse, a Pushkin setting from 1913. In gratitude to his patron, Medtner dedicated his Third Piano Concerto to the Maharajah of Mysore.

Music

Piano sonatas

The First Piano Sonata in F minor, Op. 5, is a four-movement work from 1901–3 suggesting the style of Scriabin or Rachmaninoff, but nonetheless original. Medtner’s craft gained subtlety and complexity in later years, but this work is already evidence of his mastery of musical structure. An opening Allegro, dramatic and imbued like much Russian music with a bell-like sonority, is separated by an Intermezzo from a Largo divoto that reaches a Maestoso climax before plunging into the headlong Allegro risoluto finale.

The Second, Third and Fourth piano sonatas are unrelated one-movement works. They were written during the period 1904–07 and published as the “Sonata-Triad”, Op. 11. The first of the trio, in A♭, is an ecstatic work with attractive, lyrical themes, prefaced by a poem by Goethe. The second, in D minor, is entitled “Sonate-Elegie”. It opens slowly with one of Medtner’s best-known themes and closes with an animated coda (Allegro molto doppio movimento, in D major) based on the second subject. The third, in C, returns to the lyricism of the first.

The Fifth and formerly the most popular of his sonatas is the G minor, Op. 22, written in 1909–1910. The piece alternates a slow introduction with a three-theme, propulsive sonata movement, one of whose themes was heard in the Introduction. The emotional center of this compact work (sixteen minutes in duration) is the Interludium: Andante lugubre: this comprises most of the development section and contains some of Medtner’s loveliest harmonies. There are historic recordings by Moiseiwitch and Gilels.

The Sixth Sonata followed soon after, the first of two that comprise his Op. 25. It bears the title “Sonata-Skazka”, usually translated as “Fairy Tale Sonata”. This short work in C minor, written in 1910–11, is in three movements; the second and third are connected. The first movement is a compact sonata-form, the slow movement rondo-like (the similarity to one melody by Rachmaninoff is coincidental, as the latter was not written until some thirty years later). A minatory final march with variations ends with a Coda that revisits earlier material. This was the only Medtner sonata that Rachmaninoff performed.

The other half of Op. 25 is entirely different. The Seventh Sonata in E minor, Night Wind, after Fyodor Tyutchev‘s 1832 poem “Of what do you howl, night wind…?” (Russian: О чем ты воешь, ветр ночной…?, tr. O chem ty voesh’, vetr nochnoy…?), an excerpt of which provides an epigraph, was completed in 1911 and dedicated to Sergei Rachmaninoff, who immediately recognised its greatness. It is a vast one-movement work, lasting almost 35 minutes, in two major parts: an Introduction and Allegro sonata-form, followed by a Fantasy capped by a shadowy but active Coda, the latter entirely and ingeniously based on material presented in the Introduction. Under the title “Sonata” Medtner added a note: “The whole piece is in an epic spirit” (Вся пьеса в эпическом духе). Geoffrey Tozer said: “it has the reputation of being a fearsomely difficult work of extraordinary length, exhausting to play and to hear, but of magnificent quality and marvelous invention.”

The Eighth “Sonata-Ballade” in F♯, Op. 27, began as a one-movement work, and was expanded into its present form over the period 1912–14. It comprises a Ballade, Introduction and Finale. The tonality and some of the material make passing reference to Chopin’s Barcarolle. The first movement opens with one of Medtner’s lovely pastoral melodies. The finale, like the Piano Quintet, has a thematic connection with his Pushkin setting The Muse. Medtner himself recorded this work.

The one-movement Ninth Sonata in A minor, Op. 30, was published without a title but was known as the “War Sonata” among Medtner’s friends; a footnote “during the war 1914–1917” appeared in the 1959 Collected Edition.

The Tenth “Sonata-reminiscenza” in A minor, Op. 38, No. 1, commences a set of eight pieces entitled “Forgotten Melodies (First Cycle)”. Two further cycles followed, published as Op. 39 and 40. Both this and the following sonata were completed in 1920, the year before Medtner emigrated. This single movement is one of Medtner’s most poetic creations; as the title indicates, its character is nostalgic and wistful. Other pieces in opus 38 contain variants of the Sonata’s opening theme, such as the concluding “Alla Reminiscenza”. This sonata is nowadays the most often performed.

The Eleventh, “Sonata Tragica” in C minor, Op. 39, No. 5, concludes “Forgotten Melodies (Second Cycle)”. There is some repetition of themes in this set as well—the piece which precedes the Sonata, “Canzona Matinata”, contains a theme which recurs in the Sonata, and according to Medtner’s wishes both pieces are to be played attacca—without pause. This is also a single movement sonata-allegro form, but Allegro, dramatic and ferocious, with three themes of which one (the reminiscence from “Canzona Matinata”) does not return. A violent coda concludes. This sonata is well served by recordings, including one by Medtner in 1947.

The Twelfth Sonata, entitled “Romantica” in B♭ minor, Op. 53, No. 1, was completed at the end of 1930, along with its twin. It was premièred in Glasgow in 1931. Returning to a four-movement form, it consists of a Romance (B♭ minor), Scherzo (E♭ minor), Meditazione (B minor), and Finale (B♭ minor). The ending quotes his Sonata-Skazka, Op. 25, No. 1.

The Thirteenth Sonata, the “Minacciosa” (“menacing”) in F minor, Op. 53, No. 2, is another one-movement work. It is highly chromatic, and contains a fugue. Medtner described it as “my most contemporary composition, for it reflects the threatening atmosphere of contemporary events”. Marc-André Hamelin described it as “the most concentrated 15 minutes of music one could ever hope to play or listen to”. It was dedicated to the Canadian pianist and pupil of Scriabin, Alfred La Liberté, one of Medtner’s most loyal supporters.

The last of the sonatas, “Sonata-Idyll” in G major, Op. 56, was completed in 1937. It consists of two movements: a short Allegretto cantabile Pastorale and a sonata allegro Allegro moderato e cantabile (sempre al rigore di tempo).

Other works

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 33 (1914–18). Dedicated to the composer’s mother, this one-movement work opens with an exposition section setting out the material for the work, the opening pages of which erupt with fireworks from the piano against a surging orchestral statement of the subject. A set of variations make up the central development before the opening returns two thirds of the way through the piece. Eventually the coda sets out the romantic “big tune” before the final pages lead to an unexpectedly bittersweet ending.

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 50 (1920–27). Dedicated to Rachmaninoff, who dedicated his own Fourth Concerto to Medtner. In three movements: Toccata, and a Romanza from which follows a Divertimento. The first movement is propulsive with kinetic energy, and there is much dialogue between piano and orchestra (a subsidiary theme resembles the Fairy Tale from the Op. 14 (1906–07) pair, the March of the Paladin). The Romanza and Divertimento are each in their own way varied in character, the Divertimento particularly rich in inspiration.

Piano Concerto No. 3 in E minor “Ballade”, Op. 60, 1940–43. The factors which led to the creation of this work are closely connected to the circumstances of his final years. It is dedicated to his generous patron, the Maharajah of Mysore. Three connected movements: the first, Con moto largamente, sustained and profound, slowly developing motion and energy; the second an Interludium, Allegro, molto sostenuto, misterioso quotes the first movement and prefigures the finale; a lengthy Allegro molto. Svegliando, eroico vigorously concludes the work. Medtner recorded all three Concertos with the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1947.

Violin Sonata No. 3 in E minor, Op. 57 (1938). Recorded by David Oistrakh, among others. A vast work in four movements, a counterpart to his Night Wind Piano Sonata, No. 7. Introduzione – Andante meditamente, Scherzo – Allegro molto vivace, leggiero, Andante con moto, Finale – Allegro molto. A motto theme in the Introduction juxtaposes chords quietly but insistently, joined by a melody on the violin. The melody becomes the first theme of the – lengthy – sonata-form movement that follows, juxtaposed with other themes including a march in imitation. The folksy and syncopated Scherzo in A minor, thematically related to the opening movement’s faster sections, is in Rondo-form. After a reminiscence of the motto, the Andante is a lament in F minor, extremely Russian in sentiment. The virtuoso Finale has thematic elements related to Russian Orthodox liturgical music (Medtner was born Lutheran but late in life converted to Orthodox).

The Piano Quintet in C major, Op. posth., was published after the composer’s death. He worked on sketches of the work from 1903 until its completion in 1949. Medtner considered it the ultimate summary of his musical life. Due to Medtner’s illness, the piano part in the work’s premiere was taken by Colin Horsley. Medtner’s recording of the work with the Aeolian Quartet, unpublished at the time, has recently been released on the St Laurent label.

Legacy

Geoffrey Tozer recorded almost all of Medtner’s works for the piano including all the concertos and sonatas. Hamish Milne has recorded most of the solo piano works, while Geoffrey Douglas Madge, Konstantin Scherbakov and Yevgeny Sudbin have recorded the three piano concertos. Other pianists who championed Medtner’s work and left behind recordings include Benno Moiseiwitsch, Sviatoslav Richter, Edna Iles, Emil Gilels, Yevgeny Svetlanov and Earl Wild. In modern times, pianists noted for their advocacy include Ekaterina Derzhavina, Marc-André Hamelin, who is responsible for the first-ever complete recording of all 14 piano sonatas, Malcolm Binns, Irina Mejoueva (ja), Nikolai Demidenko, Anna Zassimova, Boris Berezovsky, Paul Stewart, Dmitri Alexeev, Evgeny Kissin, Andrey Ponochevny, Konstantin Lifschitz, Daniil Trifonov, Gintaras Januševičius, and Alessandro Taverna.

Far fewer singers have tackled the songs. Medtner himself recorded a selection with the sopranos Oda Slobodskaya, Tatiana Makushina, Margaret Ritchie and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. In recent times Susan Gritton and Ludmilla Andrew have recorded complete CDs with Geoffrey Tozer, as has Caroline Vitale with Peter Baur. The bass-baritone Vassily Savenko has recorded a considerable number of Medtner songs with Boris Berezovsky, Alexander Blok and Victor Yampolsky. A handful of other singers have included Medtner songs in compilations; particularly notable are historic recordings by Zara Dolukhanova and Irina Arkhipova. However, many songs are not available on CD, and some await their first recording. A substantial two-CD set, presenting fifty-four Medtner songs, accompanied by Iain Burnside, has appeared in 2018.

Medtner recorded piano rolls of some of his works for Welte-Mignon in 1923 and Duo-Art in 1925, before his later studio recordings for Capitol Records and other labels.

In 2017 the Ukrainian pianist Darya Dadykina and the Russian pianist Vasily Gvozdetsky founded the International Nikolai Medtner Society in Berlin to popularize is work and to advance cultural exchange in and around Europe. In October/November 2018 the society organized the 1st International Nikolai Medtner Music Festival in Berlin, which brings together artists and musicologists to perform and discuss his work (see the festival programme https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolai_Medtner

The Seventh Sonata in E minor, “Night Wind” op.25, No.2 was completed in 1911 and dedicated to Sergei Rachmaninoff, who immediately recognized its greatness. It bears this epigraph by the Russian poet Tyutchev, in which the poet sees chaos as man’s natural inheritance: What are you wailing about, night wind, what are you lamenting so frantically? What does your strange voice, now muffled and plaintive, now loud, signify? In a language intelligible to the heart you speak of torment past comprehension, and you did and at times stir up frenzied sounds in the heart! Oh, do not sing these fearful songs about ancient, native chaos! Now avidly the world of night within the soul listens to the loved story! It longs to burst out the mortal breast and to merge with the Unbounded… Oh, do not wake the sleeping tempest: beneath them chaos stirs. Medtner also added: the whole piece in epic spirit”

О чем ты воешь, ветр ночной? О чем так сетуешь безумно?.. Что значит странный голос твой, То глухо-жалобный, то шумно? Понятным сердцу языком Твердишь о непонятной муке— И роешь, и взрываешь в нем Порой неистовые звуки!.. О! страшных песен сих не пой Про древний хаос, про родимый! Как жадно мир души ночной Внимает повести любимой! Из смертной рвется он груди, Он с беспредельным жаждет слиться!.. О! бурь заснувших не буди- Под ними хаос шевелится!..

Medtner Forgotten Melodies op.39 00:00 No.1 Meditazione 05:44 No.2 Romanza 10:38 No.3 Primavera 14:52 No.4 Canzona matinata 19:08 No.5 Sonata tragica Irina Mejoueva