Clara Schumann was een internationaal gevierd pianiste en pedagoge. Na haar dood werd ze vooral herinnerd als echtgenote van Robert Schumann. Ze liet ook enkele composities na.

Hoe was Clara Schumanns jeugd?

Clara Josephine Schumann (meisjesnaam Wieck) werd in 1819 geboren te Leipzig als dochter van zangeres Marianne Wieck-Tromlitz en de gezaghebbende pianoleraar Friedrich Wieck. De ouders hadden een problematisch huwelijk. Door Friedrichs stugge karakter verliet haar moeder hem voor één van diens vrienden, met een echtscheiding als gevolg.

De vijfjarige Clara werd verder door haar vader opgevoed. Die investeerde veel in haar pianotalent. Hij onderwierp haar aan een streng studieregime, maar liet haar ook profiteren van zijn vele contacten in de concertwereld. Daarmee plaveide hij de weg voor haar latere internationale carrière.

Hoe ontmoette Clara Robert?

Toen ze negen was ontmoette ze de achttienjarige Robert Schumann tijdens een huisconcert. Het leeftijdsverschil stond een wederzijdse klik niet in de weg, mede doordat beiden behalve muziekliefde ook een passie voor literatuur en poëzie deelden.

Vader Wieck accepteerde de onstuimige Schumann als pianoleerling, maar zag geen heil in diens toenadering tot zijn dochter. Zodra Clara 18 werd vroeg Schumann haar ten huwelijk, waarop een heftige vete tussen Wieck en zijn aanstaande schoonzoon ontstond; het huwelijk werd drie jaar later via een rechtszaak bedongen.

Clara SchumannINGEKLEURDE FOTO

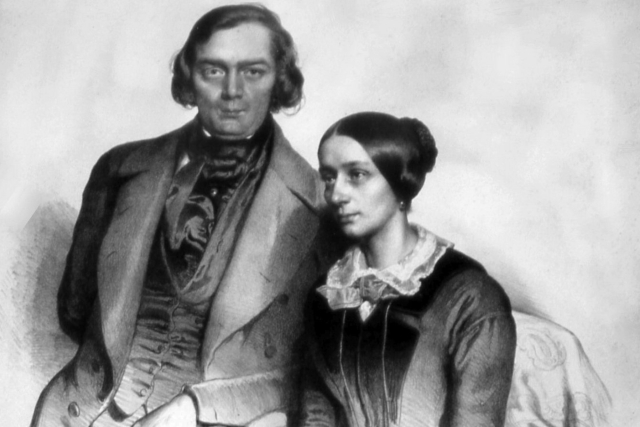

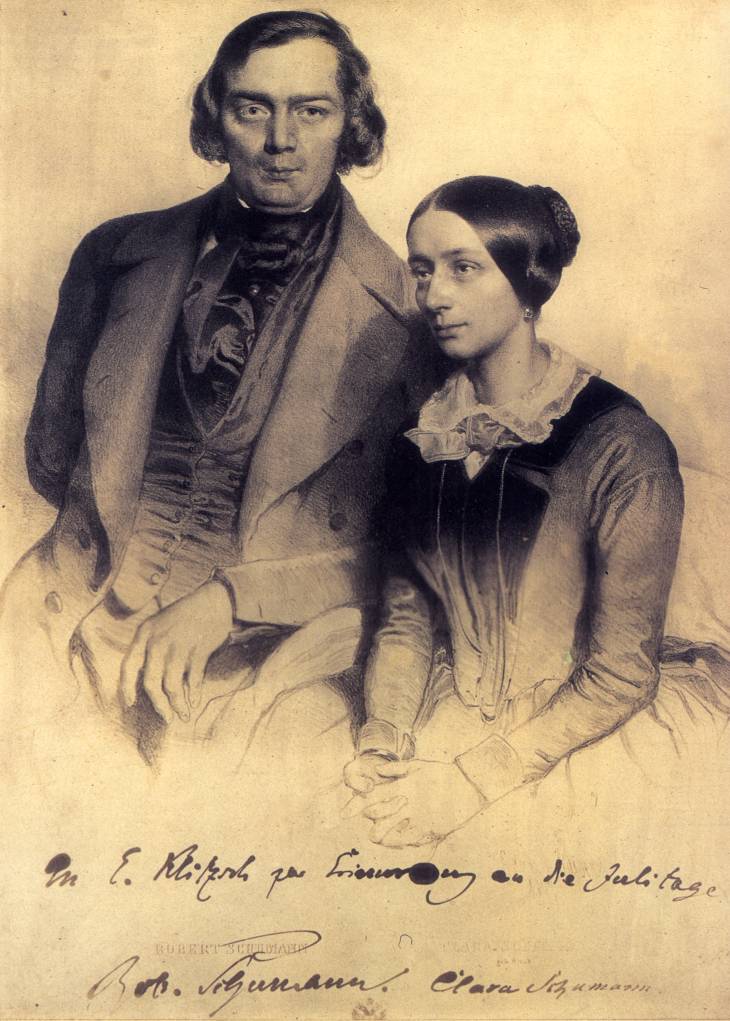

Clara SchumannINGEKLEURDE FOTO Robert en Clara SchumannLITHOGRAPHIE VAN EDUARD KAISER (1847)

Robert en Clara SchumannLITHOGRAPHIE VAN EDUARD KAISER (1847)

Intussen had Clara haar podiumdebuut gemaakt in diverse Duitse steden en tevens in Parijs en in Wenen, waar ze de hoogste muzikale onderscheiding van Oostenrijk kreeg. Tot haar bewonderaars behoorden Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt en de vioolvirtuoos Niccolò Paganini.

Hoe zat het met Clara’s relatie met Johannes Brahms?

Na de geboorte van hun eerste kind – er zouden nog zes volgen – bleef Clara optreden, maar haar compositorische ambities gaf ze op. Ook toen haar man in een krankzinnigengesticht werd opgenomen zette ze haar concertpraktijk voort om het gezin te voeden.

Na Roberts dood in 1856 kreeg haar concertcarrière vleugels. Ze promootte onder andere composities van haar man – tot dan toe slechts een plaatselijke bekendheid – en van Johannes Brahms, die als piepjong componist door de Schumanns ontdekt was en een intieme vriend was geworden. Na Roberts dood bleef Brahms altijd Clara’s adviezen zoeken, maar een fysieke relatie kregen ze niet.

Hoe overleed Clara Schumann?

Clara’s belangrijkste muzikale partner was de violist Joseph Joachim, met wie ze in Duitsland en Engeland meer dan tweehonderd keer optrad, onder meer met vioolsonates van Beethoven.

Clara Schumann werd tevens enorm gewaardeerd als pianodocente. Na haar zestigste stopte ze met intensieve concerttoernees naar het buitenland, maar zette ze haar muzikale missie voort als gewaardeerd en geliefd pianodocente aan het Hoch Conservatorium in Frankfurt.

Die functie behield zij tot haar tweeënzeventigste. Vier jaar later overleed ze aan een hersenbloeding. https://www.preludium.nl/clara-schumann

——————————-

Clara Schumann, née Clara Josephine Wieck, (born Sept. 13, 1819, Leipzig, Saxony [Germany]—died May 20, 1896, Frankfurt am Main, Ger.), German pianist, composer, and wife of composer Robert Schumann.

Encouraged by her father, she studied piano from the age of five and by 1835 had established a reputation throughout Europe as a child prodigy. In 1838 she was honoured by the Austrian court and also was elected to the prestigious Society of the Friends of Music (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde) in Vienna.

Despite strong objections from her father, she married Schumann in 1840, and they had eight children between 1841 and 1854. Though family responsibilities curtailed her career, she taught at the Leipzig Conservatory, composed, and toured frequently.

Beginning in 1853, the Schumanns developed a close professional and personal friendship with the composer Johannes Brahms that Clara maintained after her husband’s death in 1856. She edited the collected edition of her husband’s works (published 1881–93). Her own compositions include works for orchestra (among them a piano concerto), chamber music, songs, and many character pieces for solo piano.https://www.britannica.com/biography/Clara-Schumann

Robert Alexander Schumann, (born June 8, 1810, Zwickau, Saxony [Germany]—died July 29, 1856, Endenich, near Bonn Prussia [Germany]), German Romantic composer renowned particularly for his piano music, songs (lieder), and orchestral music. Many of his best-known piano pieces were written for his wife, the pianist Clara Schumann.

The Early Years

Schumann’s father was a bookseller and publisher. After four years at a private school, the boy entered the Zwickau Gymnasium (high school) in 1820 and remained there for eight years. He began his musical education at the age of six, studying the piano. In 1827 he came under the musical influence of the Austrian composer Franz Schubert and the literary influence of the German poet Jean Paul Richter, and in the same year he composed some songs.

In 1828 Schumann left school and, under family pressure, reluctantly entered the University of Leipzig as a law student. But at Leipzig his time was devoted not to the law but to song composition, improvisation at the piano, and attempts to write novels. For a few months he studied the piano seriously with a celebrated teacher, Friedrich Wieck, and thus got to know Wieck’s nine-year-old daughter Clara, a brilliant pianist who was just then beginning a successful concert career.

In the summer of 1829 he left Leipzig for Heidelberg. There he composed waltzes in the style of Franz Schubert, afterward used in his piano cycle Papillons (Opus 2; 1829–31), and practiced industriously with a view to abandoning law and becoming a virtuoso pianist—with the result that his mother agreed to allow him to return to Leipzig in October 1830 to study for a trial period with Wieck, who thought highly of his talent but doubted his stability and capacity for hard work.

Schumann’s Opus 1, the Abegg Variations for piano, was published in 1831. An accident to one of the fingers of his right hand, which put an end to his hopes of a career as a virtuoso, was perhaps not an unmitigated misfortune, since it confined him to composition. For Schumann, this was a period of prolific composition in piano pieces, which were published either at once or, in revised forms, later. Among them were the piano cycles Papillons and Carnaval (composed 1833–35) and the Études symphoniques (1834–37; Symphonic Studies), another work consisting of a set of variations.

In 1834 Schumann became engaged to Ernestine von Fricken, but, long before the engagement was formally broken off (January 1, 1836), he fell in love with 16-year-old Clara Wieck. Clara returned his kisses but obeyed her father when he ordered her to break off the relationship. Schumann found himself abandoned for 16 months, during which he wrote the great Fantasy in C Major for piano and edited the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a periodical that he had helped to found in 1834 and of which he had been editor since early 1835. In 1837 Schumann formally asked Clara’s father for permission to marry her, but Wieck evaded his request. The couple were finally married in 1840 after Schumann had gone to court to set aside Wieck’s legal objection to the marriage.

The Mature Years

Robert Schumann: DavidsbündlertänzeSecond dance from Robert Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze, Opus 6; from a 1953 recording by pianist Reine Gianoli.© Cefidom/Encyclopædia Universalis

Schumann had by now entered upon one of his most fertile creative periods, producing a series of imaginative works for piano. Among these are the Davidsbündlertänze (composed 1837), Phantasiestücke (1837), Kinderszenen (1838; Scenes from Childhood), Kreisleriana (1838), Arabeske (1838), Humoreske (1838), Novelletten (1838), and Faschingsschwank aus Wien (1839–40; Carnival Jest from Vienna). Schumann wrote most of Faschingsschwank while on a visit to Vienna, during which he unearthed a number of manuscripts by Franz Schubert, including that of the Symphony in C Major (The Great). In 1840 Schumann returned to a field he had neglected for nearly 12 years, that of the solo song; in the space of 11 months (February–December 1840) he composed nearly all the songs on which much of his reputation rests: the cycles Myrthen (Myrtles), the two Liederkreise (Song-Cycles) on texts by Heinrich Heine and Joseph Eichendorff, Dichterliebe (Poet’s Love) and Frauenliebe und Leben (Woman’s Love and Life), and many separate songs.Robert Schumann: Piano Concerto in A MinorThird movement, “Allegro vivace,” of Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, Opus 54; from a 1952 recording featuring pianist Clara Haskil and the La Haye Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Willem van Otterloo.© Cefidom/Encyclopædia Universalis

Clara had been pressing him to widen his scope, to launch out in other media—above all, the orchestra. Now in January–February 1841 he composed the Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major, which was immediately performed under the composer Felix Mendelssohn at Leipzig; an Overture, Scherzo, and Finale (April–May); a Phantasie for piano and orchestra (May), which was expanded into the famous Piano Concerto in A Minor by the addition of two more movements in 1845; another symphony, in D minor (June–September); and sketches for an uncompleted third symphony, in C minor. After this the orchestral impulse was temporarily spent.

In another new departure, Schumann in 1842 wrote several chamber works, the finest being the Piano Quintet in E-flat Major. The year 1843 was marked by Schumann’s most ambitious work so far, a “secular oratorio,” Das Paradies und die Peri (Paradise and the Peri). He made his debut as a conductor—a role in which he was invariably ineffective—with its first performance in December of that year.

During Schumann’s work on The Peri, the newly founded Leipzig Conservatory had been opened with Mendelssohn as director and Schumann as professor of “piano playing, composition, and playing from score”; again he had embarked on activities for which he was unsuited. The first few months of 1844 were spent on a concert tour of Russia with Clara, which depressed Schumann by making him conscious of his inferior role. On returning to Leipzig he resigned the editorship of the Neue Zeitschrift. In the autumn of 1844 his work was interrupted by a serious nervous collapse. From late 1844 to 1850 he and Clara lived in Dresden, where his health was gradually restored. In 1845 he began another symphony, No. 2 in C Major, but because of aural nerve trouble nearly 10 months passed before the score was finished. Schumann wrote the incidental music to Lord Byron’s drama Manfred in 1848–49.

Robert Schumann: Cello Concerto in A MinorThird movement, “Sehr lebhaft” (“Very lively”), of Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A Minor, Opus 129; from a 1953 recording featuring cellist Pablo Casals and the Prades Festival Orchestra conducted by Casals.© Cefidom/Encyclopædia Universalis

Schumann’s attempts to obtain posts in Leipzig and Vienna had also been abortive, and in the end he accepted the post of municipal director of music at Düsseldorf. At first things went tolerably well; in 1850–51 he composed the Cello Concerto in A Minor and the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major (the Rhenish) and drastically rewrote the 10-year-old Symphony in D Minor, ultimately published as No. 4. He also conducted eight subscription concerts, but his shortcomings as a conductor became obvious, and in 1853 he lost his post as music director at Düsseldorf.

Schumann’s nervous constitution had never been strong. He had contemplated suicide on at least three occasions in the 1830s, and from the mid-1840s on he suffered periodic attacks of severe depression and nervous exhaustion. His musical powers had also declined by the late 1840s, though some of his works still display flashes of his former genius. By 1852 a general deterioration of his nervous system was becoming apparent. On February 10, 1854, Schumann complained of a “very strong and painful” attack of the ear malady that had troubled him before; this was followed by aural hallucinations. On February 26 he asked to be taken to a lunatic asylum, and the next day he attempted suicide by drowning. On March 4 he was removed to a private asylum at Endenich, near Bonn, where he lived for nearly two and a half years, able to correspond for a time with Clara and his friends. He died there in 1856.

NOTABLE WORKS

- “Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 47”

- “Konzertstück, Op. 86”

- “Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54”

- “Frauenliebe und -leben”

- “Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major”

- “New Journal for Music”

- “Symphonic Studies”

- “Kreisleriana”

- “Rhenish Symphony”

MOVEMENT / STYLE

NOTABLE FAMILY MEMBERS

- Spouse Clara Schumann

Legacy

As a composer Schumann was first and most naturally a miniaturist. Until after his marriage the great bulk of his work—including that by which he is best known—consisted of short piano pieces and songs, two genres so closely related in his case as to be hardly more than two facets of the same. The song accompaniments are often almost self-sufficient piano pieces, and the piano pieces often seem to have been melodically inspired by lyrical poems. Even when the musical idea did not originate in literature but as a waltz, polonaise, or some other striking harmonic progression found at the piano by his improvising fingers, it was usually given a quasi-literary title or brought into relationship with some literary idea.

Robert Schumann: Toccata in C MajorRobert Schumann’s Toccata in C Major, Opus 7; from a 1954 recording by pianist Samson François.© Cefidom/Encyclopædia Universalis

Much of Schumann’s most characteristic work is introverted and tends to record precise moments and their moods. But another side of his complex personality is evident in the forthright approach and strongly rhythmic patterns of such works as the Toccata (1829–32) and the Piano Quintet. These two aspects are reflected in the two self-projections—the heroically aspiring Florestan and the dreamily introspective Eusebius—into which Schumann analyzed his own character and which he drew upon in an autobiographical novel, his critical writings, and much of his music.Robert Schumann: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major (Rhenish)Second movement, “Scherzo,” of Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major (Rhenish), Opus 97; from a 1954 recording by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Paray.© Cefidom/Encyclopædia Universalis

Schumann’s early music—and much of the later—is full of enigmas, musical quotations (usually in subtle disguises), and veiled allusions. In the field of the piano miniature and the pianistic song, he is a supreme master; in the simpler kind of lyrical inspiration and in the invention of musical aphorisms, he has seldom been surpassed. When Schumann embarked on more ambitious composition, his success was less assured. He was uncertain in writing for the orchestra and relied too often on safe routine procedures; his string writing was pianistic; and his most characteristic musical ideas, which he had hitherto been content to fit together in mosaics or remold plastically by variation, were seldom suited for development on a large scale. Nor in sustained musical thought did he find a satisfaction comparable with the smaller creations of his private dreamworld. Given such innate limitations, it is astonishing that Schumann was able to construct a symphony as firmly welded as the No. 4 in D Minor or a first movement as organic as that of the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major and that he could conceive orchestral music of such gloomy power as the Manfred overture or the penultimate movement of the Symphony No. 3. Some of his large-scale works, such as the Piano Concerto and the Piano Quintet, depend overmuch on the piano for their salvation, but the piano certainly saved them. Schumann did manage to create large musical forms that could communicate his own special brand of intimate poetry and unforced nobility.

It was long customary to detect in the works of Schumann’s last years evidence of his approaching collapse. But he had been mentally unstable all his life, haunted by fears of insanity since the age of 18, and the change of style noticeable in the music of the early 1850s—the increasing angularity of his themes and complication of his harmony—may be attributed to other causes, including the influence of J.S. Bach. Schumann was rightly considered an advanced composer in his day, and he stands in the front rank of German Romantic musical figures. Even his critical writing, which is as fantastic, subjective, and lyrical as his early music, constitutes a valuable document of the trend and period. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Schumann/Legacy

The Piano Trio in G minor by Clara Schumann was written in 1846, and is labeled as opus 17. It has been called “probably” the “masterpiece” among Clara’s compositions. The work is written for a piano trio comprising piano, violin, and cello. It has four movements: Allegro moderato in G minor, in common (4/4) time with a tempo of 152 quarter notes to the minute. Scherzo and Trio in B-flat major and E-flat major, respectively. The Scherzo is in 3/4 time and has a tempo of 160 quarter notes to the minute. The Trio is also in 3/4 time and shows no change in tempo from the Scherzo. Andante in G major, in 6/8 time and 112 eighth notes to the minute. Allegretto in G minor, in 2/4 time and 96 quarter notes to the minute. Clara Schumann (née Clara Josephine Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German musician and composer, considered one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era. She exerted her influence over a 61-year concert career, changing the format and repertoire of the piano recital and the tastes of the listening public. Her husband was the composer Robert Schumann. Together they encouraged Johannes Brahms. She was the first to perform publicly any work by Brahms. She later premiered some other pieces by Brahms, notably the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel. I don’t own the audio nor the scores shown in the video. audio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hz87G… / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NcQIz… / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lCsG_… / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NcQIz…

Live recording from 1985 Vladimir Ashkenazy: Robert Schumann – Papillons Opus 2 0:19 Introduction 0:32 Nr. 1 Waltz (D major) 1:13 Nr. 2 Waltz – Prestissimo (E-flat major) 1:35 Nr. 3 Waltz (F-sharp minor) 2:35 Nr. 4 Waltz (A major) 3:21 Nr. 5 Polonaise (B-flat major) 4:44 Nr. 6 Waltz (D minor) 5:42 Nr. 7 Waltz – Semplice (F minor) 6:46 Nr. 8 Waltz (C-sharp minor) 7:51 Nr. 9 Waltz – Prestissimo (B-flat minor) 8:30 Nr. 10 Waltz – Vivo (C major) 10:29 Nr. 11 Polonaise (D major) 13:00 Nr. 12 Finale (D major)

Live recording from the Chorégies d’Orange – Frankreich, 2002 Evgeny Kissin – piano Robert Schumann – Sonata No 1 in F# minor, Op. 11 0:13 First movement: un poco adagio, Allegro vivace 11:27 Second movement: Aria (Senza passione ma espressivo) 14:51 Third movement: Scherzo e Intermezzo: Allegrissimo – Lento alla burla ma pomposo – Tempo primo 19:16 Fourth movement: Allegro un poco maestoso Subscribe to the channel for more content: https://goo.gl/GLSuto

Ashish Xiangyi Kumar: It’s very rare to find a recording that puts a pretty big distance between itself and all the rest, but this fits the bill. It’s slightly slower than the norm, but the staccato is brilliantly crisp, the tempo relentlessly constant (as befits the form), the aural effects bewildering, the voicing crystal-clear, and the octave passage at 3:41 frankly superhuman.

Märchenbilder Op.113 Martin Stegner Viola Tomoko Takahashi Klavier Live Lunchconcert Philharmonie Berlin www.martinstegner.de

Robert Schumann, Carnaval Op. 9 Part II 10. A.S.C.H. – S.C.H.A: Lettres Dansantes 11. Chiarina 12. Chopin 13. Estrella 14. Reconnaissance 15. Pantalon et Colombine 16. Valse Allemande Intermezzo: Paganini

I. Sostenuto assai – Allegro ma non troppo ∙ II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace ∙ III. Adagio espressivo ∙ IV. Allegro molto vivace ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester – Frankfurt Radio Symphony ∙ Marek Janowski, Dirigent ∙Website: http://www.hr-sinfonieorchester.de ∙ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/hrsinfonieorc…

Teatro La Fenice – Musikàmera stagione di musica da camera alla Fenice 2017/18 Rafał Blechacz in recital Robert Schumann, Piano Sonata No. 28 in A, Op. 101 00:26 So rasch wie möglich (Più veloce possibile) 06:38 Andantino. Getragen (Andantino) 10:47 Scherzo. Sehr rasch und markiert (Molto veloce e marcato) 12:18 Rondo. Presto

Recording is now available: https://bc.lnk.to/schumann_romancesFA The Three Romances for Oboe and Piano, Op. 94 is a composition by Robert Schumann. In this version of the 2d movement, the interpreters are Céline Moinet (oboe) and Florian Uhlig (piano). The video is directed by Joachim Thôme.

Steinway Artist Yuja Wang is a contributor to the burgeoning library of the Steinway & Sons Spirio: the high-resolution player piano. You can learn more about Spirio at www.steinway.com/spirio and witness Yuja’s signature how-does-she-do-that style on display in Schumann’s “Der Kontrabandiste” (The Smuggler) in this video.

Robert Schumann Bunte Blätter, Op 99 Stucklein No 1 Stucklein No 2 Stucklein No 3 Albumblatter No 1 Albumblatter No 2 Albumblatter No 3 Albumblatter No 4 Albumblatter No 5 Novellette Praludium Marsch Abendmusik Scherzo Geschwindmarsch Sviatoslav Richter, piano Support us on Patreon and get more content: https://www.patreon.com/classicalvault

Very insightful interpretations of two of Schumann’s greatest piano works. Recorded in 1991.

Robert Schumann – Kinderszenen Op. 15, “Scenes From Childhood”, 1838. 00:38 Scene No.1 | Von fremden Ländern und Menschen (Of Foreign Lands and Peoples) http://youtu.be/7lihXS3GLw0 02:09 Scene No.2 | Kuriose Geschichte (A Curious Story) 03:15 Scene No.3 | Hasche-Mann (Blind Man’s Bluff) 03:48 Scene No.4 | Bittendes Kind (Pleading Child) 04:38 Scene No.5 | Glückes genug (Happy Enough) 05:17 Scene No.6 | Wichtige Begebenheit (An Important Event) 06:09 Scene No.7 | Träumerei (Dreaming) http://youtu.be/6z82w0l6kwE 08:43 Scene No.8 | Am Kamin (At the Fireside) 10:02 Scene No.9 | Ritter vom Steckenpferd (Knight of the Hobbyhorse) 10:43 Scene No.10 | Fast zu ernst (Almost Too Serious) 12:12 Scene No.11 | Fürchtenmachen (Frightening) 13:52 Scene No.12 | Kind im Einschlummern (Child Falling Asleep) 15:31 Scene No.13 | Der Dichter spricht (The Poet Speaks) Vladimir Horowitz in Vienna, 1987. Kinderszenen, “Scenes from Childhood”, Opus 15 is a set of thirteen pieces of music for piano written on during the spring of 1838. In this work, Schumann provides us with his adult reminiscences of childhood. When Schumann wrote Kinderszenen, he was deeply in love with Clara Wieck, soon to become his wife over the objections of her overbearing father. The composer worked at a feverish pace, composing these pieces in just several days. Actually, he wrote about thirty small pieces, but trimmed them to the thirteen that comprise the set. The 13 pieces showcase their creator’s musical imagination at the peak of its poetic clarity. As a result, the Kinderszenen have long been staples of the repertoire as utterly charming yet substantial miniatures, the sort of compact keyboard essays in which Schumann’s genius found full expression. In March of that year, Schumann wrote to Clara, “I have been waiting for your letter and have in the meantime filled several books with pieces…. You once said to me that I often seemed like a child, and I suddenly got inspired and knocked off around 30 quaint little pieces…. I selected several and titled them Kinderszenen. You will enjoy them, though you will need to forget that you are a virtuoso when you play them.” The Kinderszenen are a touching tribute to the eternal, universal memories and feelings of childhood from a nostalgic adult perspective. They are fairly simple in terms of execution, and, of course, their subject matter deals with the world of children. From spirited games to sleeping and dreaming, Kinderszenen captures the joys and sorrows of childhood in a series of musical snapshots. Schumann described the titles as “nothing more than delicate hints for execution and interpretation”. Schumann claimed that the picturesque titles attached to the pieces were added as an afterthought in order to provide subtle suggestions to the player, a model Debussy followed decades later in his Preludes. Scene No. 1, “Von fremden Ländern und Menschen” (Of Foreign Lands and People), opens with a lovely melody whose basic motivic substance, by appearing in several vague guises throughout many of the other pieces, serves as a general unifying element. The seventh Scene, “Träumerei” (Reverie), is easily the most famous piece in the set; its charming melody and quieting power have recommended it to generations of concert pianists who wish to calm audiences after a long series of rousing encores. The Kinderszenen contain many delicate musical touches; Scene No. 4, “Bittendes Kind” (Pleading Child), for example, is harmonically resolved only when an unseen force (a parent?) gives in and grant the child’s wish at the beginning of No. 5, “Glückes genug” (Quite Happy). In the final piece, “Der Dichter spricht” (The Poet Speaks), Schumann removes himself just a bit from the indulgent reverie to formulate a narrator’s omniscient view of the child. Quietly, gently, the many moods and feelings that Schumann touched upon over the course of this remarkable 20-minute work are lovingly recalled, and the composition concludes, contentedly, in the same key of G major in which it began. The seventh item here, “Träumerei” (Dreaming), is the most popular in the set. It is a depiction of childhood innocence, vulnerability and gentleness. Many pianists have interpreted this piece in a sentimental, almost saccharine way, while others (Horowitz notably) have insisted on a more objective approach. The main theme is sweetly innocent and sentimental, clearly representing the adult Schumann’s fond view of aspects of his own childhood. The melody is unforgettable, the harmonies simple, but distinctive, and the overall mood dreamy and soothing. Of the many themes associated with children – that in Brahms’ Lullaby, several in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf – the “Träumerei” melody is among the most memorable. The whole piece lasts under three minutes, but is the longest in the Kinderszenen set. Kinderscenen, Cenas Infantis, Infanaĝaj scenoj, Scènes d’enfants, Scene infantili, Barndomsscener, 子供の情景.

Live online: Simon Rattle conducts Brahms and Schumann: http://www.digitalconcerthall.com/con… Complete performances of the symphonies by Brahms and Schumann have been among the outstanding events of Sir Simon Rattle’s era with the Berliner Philharmoniker in recent years. In September 2014, the orchestra and its conductor will directly juxtapose the two composers’ symphonies: a fascinating double portrait, live online and in cinemas. In our intermission video intermission, Simon Rattle talks about Brahms and his friend and patron Schumann. The Berliner Philharmoniker’s Digital Concert Hall: http://www.digital-concert-hall.com Subscribe to our newsletter: http://www.digitalconcerthall.com/new… Website of the Berliner Philharmoniker: http://www.berliner-philharmoniker.de

Robert Schumann Bunte Blätter op.99 Drei Stücklein n°1 Nicht schnell, mit Innigkeit n°2 Sehr rasch n°3 Frisch Fünf Albumblätter n°4 Ziemlich langsam n°5 Schnell n°6 Ziemlich langsam, sehr gesangvoll n°7 Sehr langsam n°8 Langsam n°9 Novelette. Lebhaft n°10 Präludium. Energisch n°11 Marsch. Sehr getragen n°12 Abendmusik. Im Menuetttempo n°13 Scherzo. Lebhaft n°14 Geschwindmarsch. Sehr markiert Grigory Sokolov Live recording, Barcelona, 18.II.2020

Robert Schumann’s Violin Concerto in D minor, WoO 23 was his only violin concerto and one of his last significant compositions, and one that remained unknown to all but a very small circle for more than 80 years after it was written. In 1937 Georg Kulenkampff gave the premiere of the rediscovered Violin Concerto in D minor, which had been studied and suppressed by Joseph Joachim, but which Kulenkampff now revived with the help of Georg Schünemann, the Nazi-appointed Director of the “Prussian State Library” (German: Preußische Staatsbibliothek), where the autograph score was housed, and Paul Hindemith, whose compositions were already banned by the Nazi authorities. The addition of this work to the repertoire was a very important and successful affair, and soon afterwards Kulenkampff made this world premiere recording. Note! There are short pauses between the movements (1st and 2nd and 2nd and 3rd ones).

Wolfgang Sawallisch /Geneve Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Marilyn Richardson , Ursula Buckel , Marga Schiml , Hermann Winkler , Pierre-Andre Blaser , Kurt Widmer Lausanne / Choeur RSR , Lausanne Choeur Pro Arte 1973.5.9 Ville de Genève