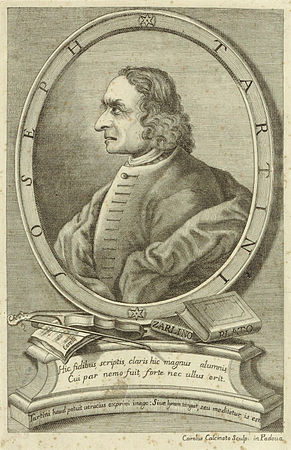

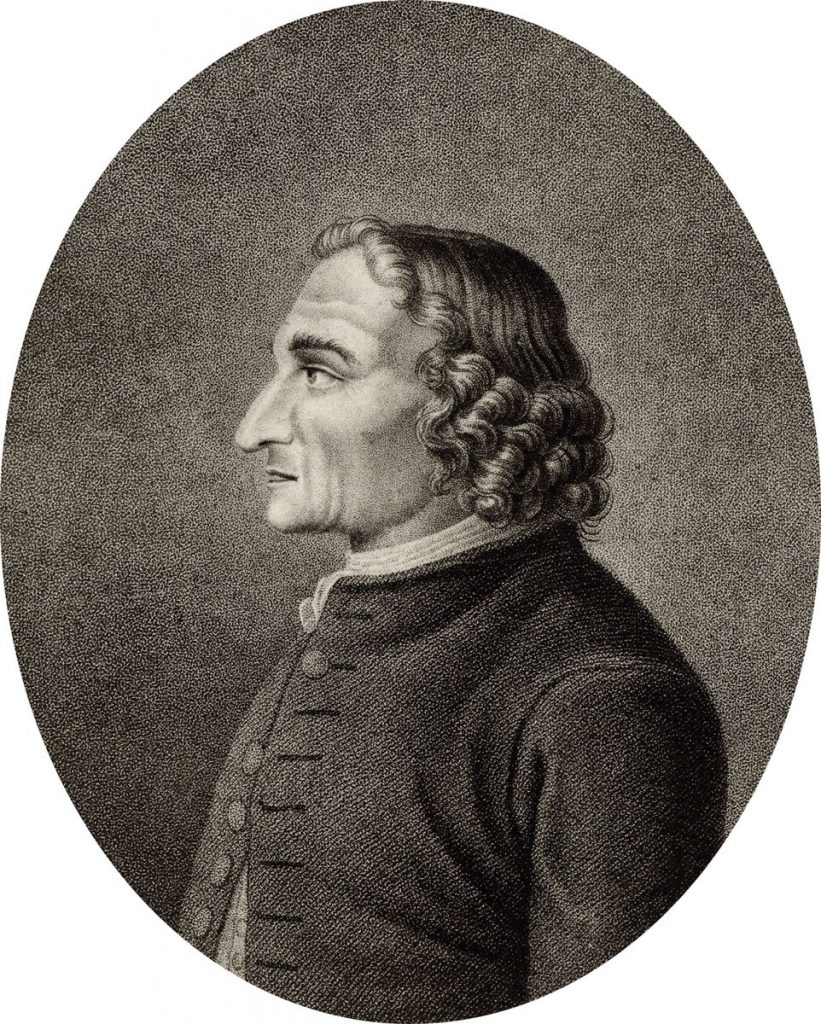

Giuseppe Tartini (8 April 1692 – 26 February 1770) was an Italian Baroquecomposer and violinist born in the Republic of Venice.

Biography

Tartini was born in Piran (now part of Slovenia ), a town on the peninsula of Istria, in the Republic of Venice to Gianantonio – native of Florence – and Caterina Zangrando, a descendant of one of the oldest aristocratic Piranese families.

It appears Tartini’s parents intended him to become a Franciscan friar and, in this way, he received basic musical training. He studied law at the University of Padua, where he became skilled at fencing. After his father’s death in 1710, he married Elisabetta Premazore, a woman his father would have disapproved of because of her lower social class and age difference. Unfortunately, Elisabetta was a favorite of the powerful Cardinal Giorgio Cornaro, who promptly charged Tartini with abduction. Tartini fled Padua to go to the monastery of St. Francis in Assisi, where he could escape prosecution. While there, Tartini took up playing the violin.

Legend says when Tartini heard Francesco Maria Veracini‘s playing in 1716, he was impressed by it and dissatisfied with his own skill. He fled to Ancona and locked himself away in a room to practise, according to Charles Burney, “in order to study the use of the bow in more tranquility, and with more convenience than at Venice, as he had a place assigned him in the opera orchestra of that city”.

Tartini’s skill improved tremendously and, in 1721, he was appointed Maestro di Cappella at the Basilica di Sant’Antonio in Padua, with a contract that allowed him to play for other institutions if he wished. In Padua he met and befriended fellow composer and theorist Francesco Antonio Vallotti.

Tartini was the first known owner of a violin made by Antonio Stradivari in 1715, which Tartini bestowed upon his student Salvini, who in turn gave it to the Polish composer and virtuoso violinist Karol Lipiński upon hearing him perform: the instrument is thus known as the Lipinski Stradivarius. Tartini also owned and played the Antonio Stradivarius violin ex-Vogelweith from 1711.

In 1726, Tartini started a violin school which attracted students from all over Europe. Gradually, Tartini became more interested in the theory of harmony and acoustics, and from 1750 to the end of his life he published various treatises. He died in Padua.

Tartini’s home town, Piran (Slovenia), now has a statue of him in the square, which was the old harbour, originally Roman, named Tartini Square (Slovene: Tartinijev trg, Italian: Piazza Tartini). Silted up and obsolete, the port was cleared of debris, filled, and redeveloped. One of the old stone warehouses is now the Hotel Giuseppe Tartini. His birthday is celebrated by a concert in the main town cathedral.

Compositions

Today, Tartini’s most famous work is the “Devil’s Trill Sonata“, a solo violin sonata that requires a number of technically demanding double stop trills and is difficult even by modern standards. According to a legend embroidered upon by Madame Blavatsky, Tartini was inspired to write the sonata by a dream in which the Devil appeared at the foot of his bed playing the violin.

Almost all of Tartini’s works are violin concerti (at least 135) and violin sonatas. Tartini’s compositions include some sacred works such as a Miserere, composed between 1739 and 1741 at the request of Pope Clement XII, and a Stabat Mater, composed in 1769. He also composed trio sonatas and a sinfonia in A. Tartini’s music is problematic to scholars and editors because Tartini never dated his manuscripts, and he also revised works that had been published or even finished years before, making it difficult to determine when a work was written, when it was revised and what the extent of those revisions were. The scholars Minos Dounias and Paul Brainard have attempted to divide Tartini’s works into periods based entirely on the stylistic characteristics of the music.

Sixty-two manuscripts with compositions of Tartini are housed at the Biblioteca comunale Luciano Benincasa in Ancona.

Luigi Dallapiccola wrote a piece called Tartiniana based on various themes by Tartini.

Theoretical work

In addition to his work as a composer, Tartini was a music theorist, of a very practical bent. He is credited with the discovery of sum and difference tones, an acoustical phenomenon of particular utility on string instruments (intonation of double-stops can be judged by careful listening to the difference tone, the “terzo suono“). He published his discoveries in a treatise “Trattato di musica secondo la vera scienza dell’armonia” (Padua, 1754). His treatise on ornamentation was eventually translated into French — though when its influence was rapidly waning, in 1771 — by a certain “P. Denis”, whose introduction called it “unique”; indeed, it was the first published text devoted entirely to ornament and, though it was all but forgotten, as only the printed edition survived, has provided first-hand information on violin technique for modern historically informed performances, once it was published in English translation by Sol Babitz in 1956. Of greater assistance to such performance was Erwin Jacobi’s published edition. In 1961, Jacobi published a tri-lingual edition consisting of the French (basis of the following two), English (translation by Cuthbert Girdlestone), plus Jacobi’s own translation into German (Giuseppe Tartini. “Traite des agréments de la musique”, trans. and ed. Erwin Jacobi. Celle: Hermann Moeck Verlag, 1961). Of significant import, Jacobi’s edition also includes a facsimile of the original Italian found in Venice in 1957, copied in the hand of Giovanni Nicolai (one of Tartini’s best known students) and including an opening section on bowing and a closing section on how to compose cadenzas not previously known. Another copy (though less complete) of the Italian original was found among manuscripts purchased by the University of California, Berkeley in 1958, a collection that also included numerous ornamented versions of slow movements of concertos and sonatas, written in Tartini’s hand. Minnie Elmer analyzed these ornamented versions in her master’s thesis at UC, Berkeley in 1959 (Minnie Elmer. “The Improvised Ornamentation of Giuseppe Tartini”. Unpublished M.A. thesis. Berkeley, 1959).

Fictional portrayal

Tartini is mentioned in Madame Blavatsky’s “The Ensouled Violin”, a short story included in the collection Nightmare Tales.

Tartini, the great composer and violinist of the XVIIIth century, was denounced as one who got his best inspirations from the Evil One, with whom he was, it was said, in regular league. This accusation was, of course, due to the almost magical impression he produced upon his audiences. His inspired performance on the violin secured for him in his native country the title of “Master of Nations”. The Sonate du Diable, also called “Tartini’s Dream” — as every one who has heard it will be ready to testify — is the most weird melody ever heard or invented: hence, the marvellous composition has become the source of endless legends. Nor were they entirely baseless, since it was he, himself; who was shown to have originated them. Tartini confessed to having written it on awakening from a dream, in which he had heard his sonata performed by Satan, for his benefit, and in consequence of a bargain made with his infernal majesty.

The folklore of the “Devil’s violin”, classically exemplified by a similar story told of Niccolò Paganini, is widespread; it is an instance of the deal with the devil. Modern variants are Roland Bowman‘s The Devil’s Violin and the country song The Devil Went Down to Georgia; the PBS segment on violin in its series “Art” was titled “Art of violin: the devil’s instrument”.

Tartini’s The Devil’s Trill is the signature work of a central character in Daniel Silva‘s The English Assassin. Anna Rolfe, the daughter of a Swiss banker, is a famous violinist and the sonata features prominently in the novel. The story of Tartini’s inspirational dream is told.

Tartini’s “The Devil’s Trill” is also featured in the Japanese anime Descendants of Darkness (Yami no Matsuei). The three part story is also named after the composition. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giuseppe_Tartini

—————————-

“One night I dreamed I had made a pact with the devil”

Giuseppe Tartini

His playing was renowned for its combination of technical and poetic qualities, and Italians proclaimed him “the finest musician in the world.” He also made a pact with the devil for his soul, and the “Devil’s Trill Sonata,” represents “a triumph of imagination which has never left the repertory.” Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) died in the year of Beethoven’s birth, 250 years ago in Pirano, then part of the Venetian Republic, now part of Slovenia.

Basilica St. Anthony Padua

Destined for a monastic career, he rejected his father’s wishes and enrolled as a law student at Padua University. According to contemporary accounts, Tartini devoted most of his time to improving his fencing and to the study of music. His secret marriage to the niece of the Bishop of Padua—I tell you more about that in an upcoming love article—necessitated his flight to Assisi. Locked away in a convent, he devoted himself to the study of the violin for at least three years. Forced to support himself, he became an itinerant violinist playing in the orchestra of the Ancona and also the Fano opera house.

Tartini eventually established himself in Venice and came under the influence of the famed violinist Francesco Veracini, who was the head of the Venetian Academy of Music. Deeply impressed by Veracini’s playing, Tartini once again withdrew for several years of solitary study to explore the principles of violin playing. A good many of his technical and acoustic discoveries and elucidations served as the “basis of every violin school in the world.” In 1721, Tartini was appointed as director of the orchestra at the Basilica of St. Anthony at Padua. The terms of his contract granted him the freedom to perform internationally, and we find him taking part in performances in Parma, Bologna, Camerino, Ferrara, and Venice. He also spent three years in Prague, initially connected to a performance for the coronation of Emperor Charles VI.

Tartini’s The Art of Bowing

However, since a Venetian innkeeper accused him of fathering her recently born child, Tartini was in no hurry to return to Italy. Ill health obliged him “against his will,” to return to Padua in 1726. His first published works were issued in Amsterdam, and he was repeatedly invited to appear in France, Germany and England. He declined all invitations, and a stroke suffered in 1740 partially paralyzed his left arm. From then on he devoted less time to playing and composing, and focused almost exclusively on theoretical matters. His noted bowing study “L’Arte del Arco” was published in Naples during his lifetime, and after nearly fifth years of service to Parma, he died there on 26 February 1770.

Tartini principally composed in two instrumental genres, the solo violin concerto with string accompaniment and the violin sonata. We know that he had been asked to write music for the opera house in Venice, but he always refused because “the human throat is not a violin fingerboard.” To this day, no satisfactory edition of Tartini’s music has been issued, principally because the composer returned over and over to his original manuscripts of finished works and added and/or deleted whole sections. In some cases he moved entire movements from one place or one piece to another. In essence, Tartini produced successive versions of the same piece, and he steadfastly refused to append dates to his musical autographs. On the other hand, we have a much clearer picture of Tartini the music theorist. Over his lifetime he accumulated a large library on music, philosophy, religion and mathematics. He engaged in serious studies of the principles of acoustics, and published his discoveries in 1754. His treatise on ornamentation was even translated into French, and his famous letter to Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen explained in great detail the bowing practices of the time.

Tartini began his teaching activities after his return to Padua from Prague, establishing his violin school “Scuola di Nazioni” in 1728. As he was internationally famous, a great many students flocked to Padua, including the well-known violinists Pugnani and Nardini. Students were taught not only violin technique but also composition, with a course of study usually lasting two years. Apparently, he paid careful attention to each individual student, accepting only nine disciples in 1737. His teaching method was focused on “clarity of execution and intonation, beauty of sound, and subtlety of expressive nuance.” Much of his teaching was based on “the mastery of the bow,” and his legacy made its way outside Italy as well. Leopold Mozart’s “Violinschule,” for one, copies the first part of Tartini’s treatise on embellishments in translation. Alongside Vivaldi and Veracini, Tartini was one of the greatest violinists of the 18th century, and he has rightfully been referred to “as the godfather of modern violin playing.”

https://interlude.hk/giuseppe-tartini/

From Tartini’s Cello Concerto D-dur. Pablo Casals (cello) and Blas Net (piano). Recorded 19 June 1929.