Penderecki (* 23. November1933 in Dębica; † 29. März2020 in Krakau) war ein zeitgenössischer polnischerKomponist, dessen Werk der postseriellen Musik zugeordnet wird und der vor allem durch seine Klangkompositionen Aufsehen erregte. Für diese speziell in der Instrumentalmusik angewandte Technik wurde von Seiten der polnischen Musikwissenschaft, namentlich von Zofia Lissa und Józef Michał Chomiński, der Begriff Sonorismus entwickelt. Er gilt als einer der führenden Komponisten der polnischen Avantgarde, der mit seiner Musik „den Kompositionsstil einer ganzen Ära der zeitgenössischen Musik mitgeprägt“ hat. Sein unerschrockenes Eintreten für christliches Gedankengut und Menschlichkeit sowie seine unverwechselbare Tonsprache ließen Penderecki zur Galionsfigur einer „polnischen Schule“ der Avantgarde werden.

Leben

Krzysztof Penderecki wurde in Dębica bei Rzeszów (nicht in Krakau, wie gelegentlich irrtümlich berichtet wird) geboren. Seine Großmutter stammte aus Armenien. Pendereckis Großvater Robert Berger war ein talentierter Maler, dessen Vater Johann, ein protestantischer Deutscher, aus Breslau nach Dębica gezogen war. Sein Vater brachte ihn schon früh mit Musik in Berührung; bereits als Kind erhielt er Violin- und Klavierunterricht. Später studierte er Komposition an der Musikakademie Krakau bei Artur Malawski und Stanisław Skołyszewski sowie privat bei Franciszek Skołyszewski; daneben studierte er an der Universität Krakau Philosophie, Kunst- und Literaturgeschichte. 1958 schloss er das Studium mit dem Diplom ab und übernahm im gleichen Jahr eine Professur für Komposition an der Musikakademie Krakau.

1959 fiel er in Polen und international auf, als er beim Warschauer Wettbewerb junger polnischer Komponisten alle drei ausgesetzten Preise für drei anonym eingereichte Werke zugesprochen erhielt. In der westlichen Welt wurde er schlagartig bekannt, als 1960 sein Werk Anaklasis für Streichorchester und Schlaginstrumente bei den Donaueschinger Musiktagen uraufgeführt wurde.

Von 1972 bis 1987 war er Rektor der Musikakademie Krakau. Zwischen 1966 und 1968 war er auch Dozent an der Folkwang-Hochschule in Essen. Penderecki war Ehrenvorsitzender des Kuratoriums des Institutes für kulturelle Infrastruktur Sachsen in Görlitz und seit 1992 Ehrenmitglied der International Society for Contemporary Music ISCM (Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik). Ab 1976 lebte er in Lusławice. 1988 wurde er zum ersten Gastdirigenten des NDR-Sinfonieorchesters (Hamburg) gewählt. 2001 war er der elfte Komponist beim jährlichen Komponistenporträt des Rheingau Musik Festivals. Er sprach fließend Deutsch. Penderecki starb nach langer Krankheit im März 2020 im Alter von 86 Jahren in Krakau.

Stilistik

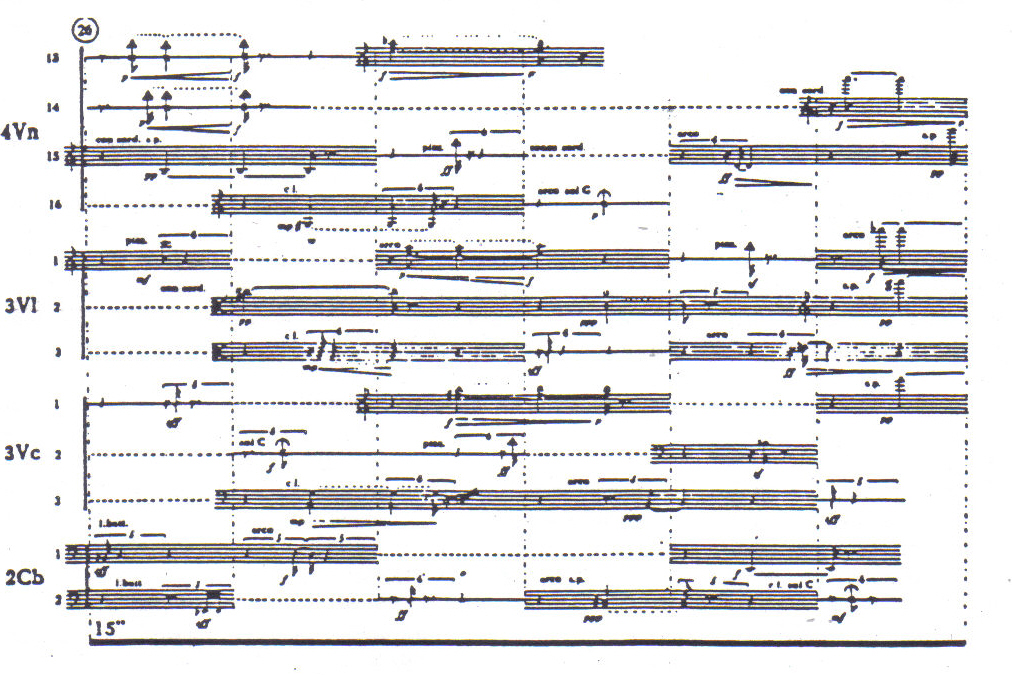

In der Musik nach 1945 führt ein direkter Entwicklungsstrang von Schönbergs Zwölftontechnik über die Kompositionen von Anton Webern zu einer „punktuellen Musik“, deren vorrangiges Ziel in der Auflösung von Melodien in Einzeltöne bestand. Komponisten wie Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono und Karlheinz Stockhausen setzten an die Stelle klassisch-romantischer Themenverarbeitung spezielle Techniken der Serialität, um die Einzeltöne zu größeren Formorganismen zusammenzufügen. Dieser hauptsächlich durch die Darmstädter Ferienkurse bekannt und rasch populär gewordenen Kompositionsweise setzte Penderecki frühzeitig eine eigene Tonsprache entgegen, in welcher die Vereinzelung der Töne aufgehoben und durch neuartige Vermassungstechniken in ihr Gegenteil verwandelt wurde. Ging es vorher darum, jeden Ton einzeln durch sog. Parameter zu definieren, gestaltete Penderecki in dem bahnbrechenden Werk Anaklasis (1959/60) Klangflächen und Klangbänder, die aus zahllosen und einzeln nicht mehr wahrzunehmenden Tönen bestanden. „Das Neuartige dieses Werks liegt in dem primär geräuschhaften Gestus, der wie mit breitem Pinsel gemalt wirkt. Penderecki arbeitete hier mit Klangbändern, Clustern, Glissandi oder auch bewegten Klangblöcken, deren Innenleben melodisch aufgefächert erscheint.“ Das Besondere des Gesamtklanges beruht unter anderem auch auf dem Einsatz ungewöhnlicher Klangerzeuger wie z. B. von Holzsägen und mechanischen Schreibmaschinen sowie in der Hinzunahme geräuschhafter Blas-, Kratz- und Zupfgeräusche auf den herkömmlichen Orchesterinstrumenten (in Fluorescences für gr. Orch. 1961/62). Die Vermassung der Einzeltöne geht so weit, dass die Grenzen und Unterschiede zwischen Schlag-, Blas- und Streichinstrumenten vom Hörer nicht mehr wahrgenommen werden können. Dabei ließ sich Penderecki primär von Entdeckerfreude und Experimentierlust leiten und inspirieren, sah seine Arbeiten aber auch als Forschungsergebnis und verlieh ihnen Titel wie beispielsweise De natura sonoris (lat.: Über die Natur des Klanges). Das akustische Erleben von Musik stand im Mittelpunkt. Ein weiteres Mittel auf diesem Weg war die Abschaffung traditioneller Rhythmen und zeitlicher Gestaltungsmittel. Mit den grafischen Mitteln einer sog. „space notation“ wurden die Dauern von Klangprozessen visuell verdeutlicht, ohne dass für die Einzelaktionen genauere Angaben gemacht wurden. So zeichnet sich auch im Notenbild für Spieler und Dirigenten eine gewisse Rahmenvorstellung ablesbar ab.

Nach einigen Jahren des Experimentierens setzte bereits in den 1960er-Jahren eine Neuorientierung ein. Hatte Penderecki in der Frühphase die Formen seiner Kompositionen aus dem Klangmaterial heraus entstehen lassen, wendete er sich nunmehr verstärkt den traditionellen Formen der Klassik und Romantik zu und strebte eine Verbindung seiner tontechnischen Neuerungen mit der Tonsprache früherer Epochen an: „Sinfonie und Konzert, Oratorium und Oper standen nun im Zentrum seines Interesses.“ Ein wichtiger Schritt in dieser Richtung war die Komposition seines 1. Streichquartetts (1960), dessen Bedeutung von musikwissenschaftlicher Seite als „Wende in der Gattungsgeschichte“ bezeichnet wurde. Während mit den Quartettkompositionen von Beethoven bis Brahms hauptsächlich in der Verarbeitung von gegensätzlichem Themenmaterial und dessen Aufspaltung in Motive ihr formaler Sinn entfaltet wurde, erhob Penderecki in seinem 1. Streichquartett die Gegensätzlichkeit von Geräusch und traditionell orthodoxem Quartettklang zur formbildenden Kraft und stiftete eine Symbiose aus klanglichen Innovationen und der traditionellen Sonatenidee. In diesem ersten Ansatz äußert sich bereits klar erkennbar Pendereckis Veranlagung zum integralen Denken. Im Lager der Musikkritik wurde Pendereckis Öffnung hin zur Formenwelt, Harmonik und Tonsprache früherer Jahrhunderte in den meisten Fällen als Absage an die Moderne interpretiert und bedauert. Dabei wurde übersehen, dass er auf diesem Wege nichts anderes und nicht weniger als eine Verbindung zwischen seinen kompositorischen Neuerungen und einem weit gefassten Musikverständnis herzustellen suchte. Hierfür findet der Komponist Peter Michael Hamel einen interessanten Vergleich, wenn er sagt, bei Penderecki sei „weniger von einem starr fixierten Personalstil als vom vielfältigen Stilwandel zu sprechen, ist Penderecki doch auch von der stets fortschreitenden Stilveränderung eines Picasso fasziniert.“In seinen Opern, Oratorien und Sinfonien bildeten inhaltliche Vorgaben, seien sie religiöser oder allgemeiner Natur, den Rahmen für eine Ausdrucksweise, die sich nicht länger auf die Schockwirkung und Überraschungseffekte avantgardistischer Klanggestaltung festlegen ließ.

Rezeption

Zwar hat Penderecki mit seiner sonoristischen Kompositionstechnik zunächst stilbildend gewirkt und die Ästhetik einer postseriellen Musik entscheidend mit entwickelt, doch gingen die Ansichten über die Bedeutung und Wirkung seines Schaffens später weit auseinander. Viele seiner frühen Werke hatten auf Grund der darin angewandten ungewöhnlichen und in sich durchaus stimmigen Kompositionstechniken anfänglich in Fachkreisen in erheblichem Maß für Aufmerksamkeit gesorgt und anregend auf die musikalische Weiterentwicklung gewirkt, doch war auch in breiten Kreisen des Konzertpublikums seit Pendereckis Wendung zur Tradition die Akzeptanz auffallend gewachsen. So hatte seine Musik relativ bald auch Einlass bei der Mailänder Scala, im Wiener Musikverein und im Salzburger Festspielhaus gefunden. Die 1986 bei den Salzburger Festspielen uraufgeführte Oper Die schwarze Maske (Text: Gerhart Hauptmann) „fand selbst der örtliche Gralshüter Herbert von Karajan offenbar so schön, dass er sie am liebsten selbst dirigiert hätte.“ Werke wie die Lukaspassion, das Polnische Requiem und das Dies irae hatten vor allem im kirchlichen Bereich zahllose Menschen erreicht, und seine Sinfonien und groß angelegten Opern überzeugten und begeisterten in erster Linie ein allgemein interessiertes Publikum. Auch dass seine Avantgarde-Techniken zunehmend von Filmmusikkomponisten, wie z. B. Don Davis und Elliot Goldenthal, eingesetzt und übernommen wurden, ist ein Indiz für die eher allgemeine Akzeptanz. Und so stand Penderecki im Lauf der Jahre immer mehr in der Kritik seiner Komponistenkollegen und bei den Kritikern. Bereits im Jahr 1972 merkt Hans Vogt an: „Penderecki ist im Konzert der gegenwärtigen Musik zweifellos eine auffallende Erscheinung. Sein Instinkt für Direktwirkungen […] hat bewirkt, dass er als einer der wenigen jüngeren Komponisten ins Bewusstsein einer größeren Öffentlichkeit gedrungen ist. Für die Gesamtsituation ist dies begrüßenswert; manches Ressentiment gegen ‚moderne Musik‘ wurde dadurch abgebaut. Für ihn selbst und seine weitere Entwicklung aber liegt darin eine gewisse Gefahr: Einmal erfolgreich, beginnt er sich in seinen letzten Jahren allzusehr zu wiederholen.“ Mit seiner sämtlichen Stilen gegenüber offenen Positionierung hatte Penderecki auf der einen Seite viel Anerkennung geerntet, und zwar von Zuhörerkreisen, die hier Zugang zur Neuen Musik gefunden zu haben glaubten. Mit Skepsis hingegen begegneten ihm Kollegen wie beispielsweise Helmut Lachenmann, der ihn als „Penderadetzky“ apostrophierte, der die „tonalen Paarhufer“ anführe.Ulrich Dibelius, einer der besten Kenner der zeitgenössischen Musik und in seinen Formulierungen stets um Objektivität bemüht, charakterisiert die neuere Entwicklung Pendereckis als „klangschwelgerische Breitspurigkeit“, basierend auf einer ungebremsten Liebe Pendereckis zur Musik von Tschaikowsky und „höchst konform mit aktuellen neoromantischen Tendenzen.” Nicht weniger deutlich klingen die Einwände gegen Pendereckis Entwicklung, wenn es andernorts heißt: Penderecki hat „auf kritische Stimmen, die ihm künstlerischer Stagnation und allzu bereitwillige Anpassung an den Kulturbetrieb vorwarfen, mit künstlerischen Argumenten geantwortet. Hinter den wohl bewusst traditionell gewählten Titeln (u.a. Partita, Sinfonie, Concerto grosso) verbergen sich Kompositionen, in denen die früheren Klangerfahrungen sich formal zwingender in ihrer Verarbeitung konsequenter artikulieren, deren Ausgewogenheit aber auch zuweilen die wilde Ungezügeltheit der früheren Klanggestik vermissen lässt.“[ Unter der markanten Überschrift: „Mit Gloria und Glykol in den Rückwärtsgang“ schreibt Klaus Umbach in einer pointierten Kritik in der Wochenzeitschrift Der Spiegel: „Der Neutöner Penderecki hat abgedankt“ und fährt fort: „Wenn nicht alles täuscht, ist der Verräter zum Vorreiter der Avantgarde geworden – im Handel mit Antiquitäten.“ Penderecki selbst äußerte sich dazu wie folgt: „In Fragen der Musik bin ich gegen jede Orthodoxie. Ich bin weder ein Feind der Tradition, noch ein kritikloser Enthusiast der Avantgarde. Überhaupt liebe ich das Theoretische nicht. Nach meiner Meinung ist in unserem Jahrhundert genug experimentiert worden: mit atonalen Mitteln, mit aleatorischer Technik, mit Elektronik. Musik muss einfach Ausdruck haben, nicht in irgendwelchen experimentellen Richtungen herumgeistern, am Publikum vorbei.“ Mit dieser Einstellung erteilte Penderecki dem Denken in Kategorien eines zu bearbeitenden musikalischen „Materials“ eine Absage und ging im Sinne einer postmodernen Kunstauffassung auf Distanz zu den wichtigen Zentren der musikalischen Avantgarde in Mitteleuropa, wo der Diskurs über Möglichkeiten der Weiterentwicklung und die Fortschrittlichkeit des Klangmaterials im Mittelpunkt stand und jede Rückwärtsorientierung kritisch registriert wurde. Immer mehr setzt sich indessen auch in Kritikerkreisen die Einsicht durch, dass Penderecki „wie kaum ein Zweiter zu jeder Zeit Tradition und Moderne miteinander verbunden und deren vermeintliche Gegensätzlichkeit fruchtbar gemacht hat.“ Wolfgang-Andreas Schultz interpretiert den Befreiungsschritt Pendereckis aus der Enge der Material-Ästhetik der 1960er Jahre als „Versuch, die ausgegrenzten Bereiche der Lebenswirklichkeit wieder in die Musik hineinzunehmen.“ Zwar scheine es „den bisherigen Versuchen mit Stilpluralismus“ noch „an einer überzeugenden Integration“ zu mangeln, doch wertet Schultz „die vielgeschmähte Postmoderne“ als „unsicher tastende Schritte in eine vielleicht doch richtige Richtung.“

Anlässlich seines Todes wurde Penderecki in einer Pressemeldung der Akademie der Künste Berlin, deren Mitglied er seit 1979 war, als „der wichtigste polnische Komponist und Dirigent des 20. Jahrhunderts“ und „einer der engagiertesten Humanisten des internationalen Musiklebens“ bezeichnet. „Durch seinen Tod verliert die Musikwelt einen Komponisten, der seit den späten 1950er Jahren bis in die jüngste Gegenwart tonangebend blieb“, schrieb die Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, und aus den Kreisen der Auschwitz-Überlebenden hieß es: „Mit seinem Werk ‚Dies Irae‘, das er 1967 zur Einweihung des vom Internationalen Auschwitz Komitee ausgeschriebenen Denkmals im Vernichtungslager Auschwitz-Birkenau komponierte, hat er die Erinnerung an alle Opfer von Auschwitz ins musikalische Gedächtnis der Menschheit eingeschrieben.“ Er hat „mit seiner Musik und seinem Erinnerungsvermögen die Dunkelheiten und die Schönheit der Welt über viele Jahrzehnte ausgeleuchtet“.

Pendereckis Werke im Film

Pendereckis expressive Musik wurde auch in Filmen eingesetzt. „Herausragend ist etwa seine Zusammenarbeit mit Martin Scorsese („Shutter Island“/2010), David Lynch („Inland Empire“/2006), Stanley Kubrick („Shining“/1980) und Andrzej Wajda („Das Massaker von Katyn“/2007).“ Bereits 1973 fanden sich Pendereckis Klänge in dem Film „Der Exorzist“ wieder (Regie: William Friedkin). Er komponierte auch die Originalmusik für die Spielfilme „Die Handschrift von Saragossa“ (1965) und „Ich liebe dich, ich liebe dich“ (1968). https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krzysztof_Penderecki

—————————————————-

Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima – Urbański, FRSO

The Extraordinary Life of Krzysztof Penderecki

As Krzysztof Penderecki celebrates his 85th (2013) birthday, we take a closer look at life and work. Where is the composer from, what does he have in common with Tadeusz Kantor, what links him do Salvador Dali? Why do Jewish motifs recur in his music? Who does he plant… mazes for, and, is he into jazz? We have the answers for you.

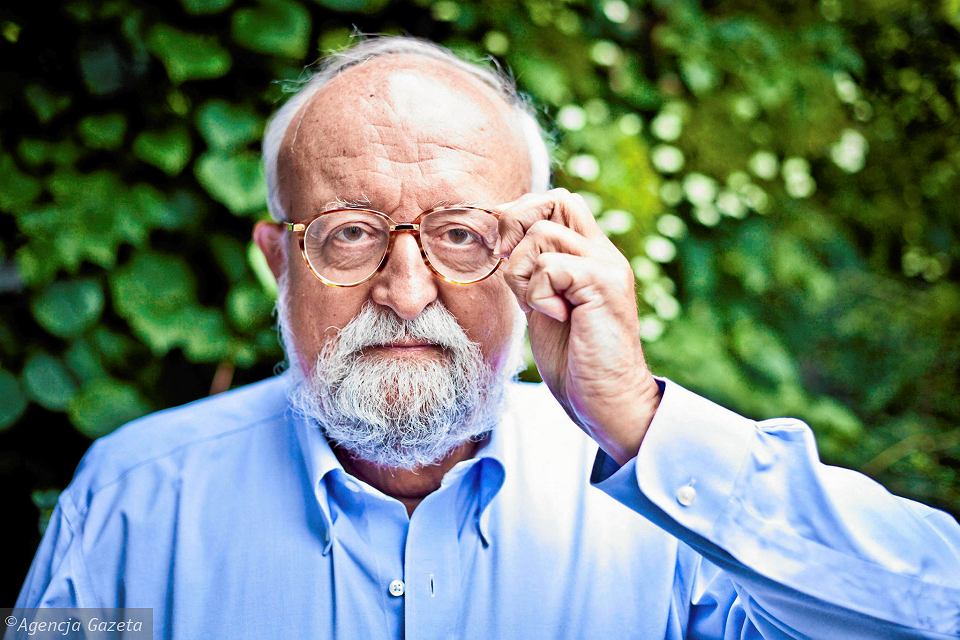

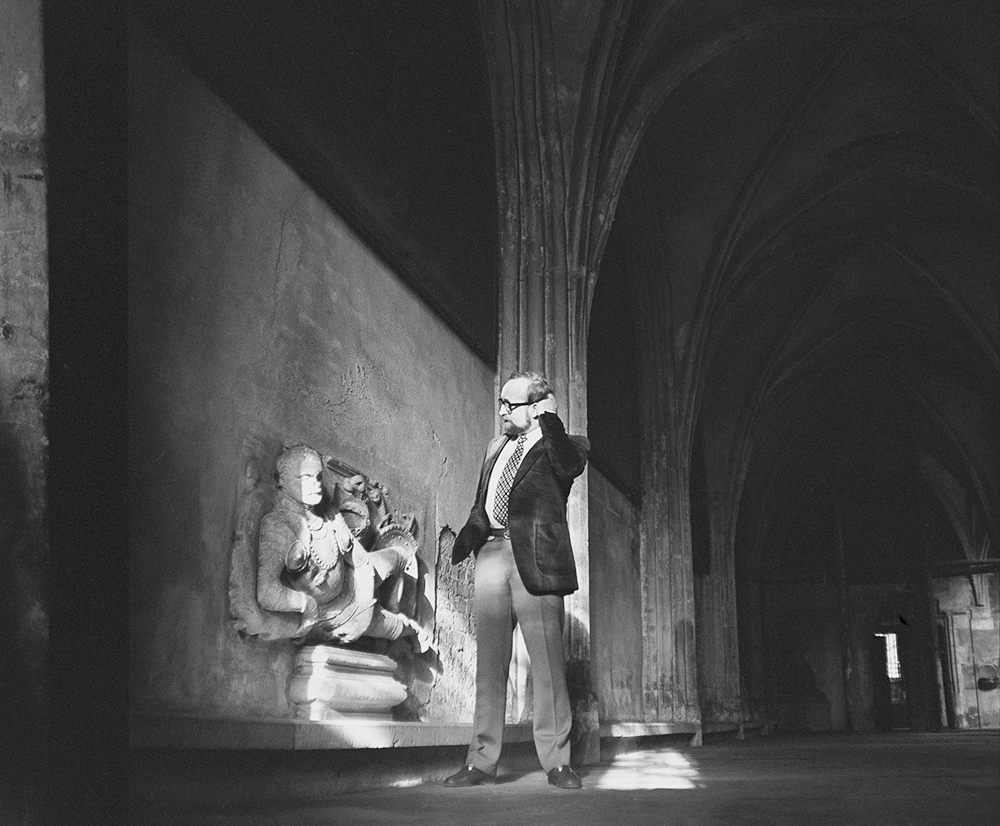

Krzysztof Penderecki, photo: Bogdan Krężel/Przekrój/Visavis.pl/Forum

Early life

Krzysztof Penderecki was born in 1933 in the town of Dębica, Dembitz in Yiddish. It was a small, provincial town and the majority of its inhabitants were Hasidic Jews. Life rolled on unhurriedly in Dębica, and its dwellers remembered the times of emperor Frans Josef and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy with a tinge of nostalgia. Hence all the Jewish echoes that resonate throughout Penderecki’s oeuvre. In an interview with Polish Radio, the composer commented:

It is strange that after all these years, the music that I had in my ears, comes back. For example, in two of my compositions klezmer music is reiterated intentionally – in the ‘Sextet’ (2000) and even in the ‘Concerto Grosso’ (2001), I most likely heard the motifs as a child.

Concerto Grosso – Krzysztof Penderecki

“Concerto Grosso” revisits concerto grosso – the Baroque practice of the orchestra being contrasted with a small group of instrumental soloists.#music#cultureRead more

Roots & family ties

Penderecki comes from a family of Armenian, German and Polish roots. His grandfather was a German Protestant, but he converted to Catholicism for his wife and became a neophyte. The composer’s grandmother, an Armenian, came from Stanisławowo, known today as Ivano-Frankivsk. She travelled from Dębica to pray in an Armenian church in Kraków. Penderecki is also related to Tadeusz Kantor. More precisely speaking, Kantor was a younger cousin of Penderecki’s mother, 20 years senior of the composer.

5 Reasons Kantor Was the Polish Artist of the Century

At the centannial anniversary of Tadeusz Kantor’s birth, we evoke five reasons for the unceasing popularity of Poland’s most famous artist of the 20th century. Art meant everything for him. What is left of it today?#photography & visual arts#performing arts#cultureRead more

Education

Unlike a great many composers, Krzysztof Penderecki did not come from a musical family. His parents sent him and his siblings to piano lessons, assuming that a well-educated man should also have some orientation in the fine arts. These lessons were a nightmare for the future musical rebel and the teacher quickly gave up on her refractory student. Sometime later, Penderecki’s father received a violin and this present incited unusual curiosity in his young son. Anyone is capable of producing a clear sound on the piano – it is enough to simply strike a key. The violin is a much more complex instrument, and the young Krzysztof decided to become a virtuoso. He practised from the early morning, before going off to school, and it was the first thing he did after coming home. A girlfriend gave him a voluminous collection of Bach’s sonatas, which Penderecki became enchanted with.

In junior high school, he founded a band and, in the words of Krzystof Lisicki, ‘became something of an animator and manager of the musical scene in Dębica’. Nowadays, we would call him a city activist. After he passed his baccalaureate exam, his parents sent him to Kraków for a year, so that he could decide for himself what direction he wanted to take. Apart from music, Penderecki was also fascinated by literature (he thought of studying classical philology) and was also attracted to the visual arts.

Awards

As we know, Penderecki chose music and quickly claimed his first merits. It could be said that he set a record right away, winning three major awards in 1959: receiving first and two second place prizes in the Young Composers’ Competition organised by the Polish Composers’ Union. The compositions were submitted anonymously and when the jury checked the winners’ identities they were rather troubled to see one composer win all three awards. They were quick to modify the rules of the contest – and since that edition, every composer is allowed to submit only one work for the competition. And so, Penderecki’s record is unbeatable.

The awarded pieces were Strofy (Stanzas) for soprano, a reciting voice and 10 instruments, David’s Psalms – based on the texts of Jan Kochanowski, and Emanations for an orchestra.

Strofy, based on Greek, Persian and Hebrew texts, became part of the programme of the Warszawska Jesień (Warsaw Autumn) festival. In his article for Ruch Muzyczny magazine, Bohdan Pociej emphasised that Penderecki’s reading of antiquity is thoroughly innovative and contemporary. But the legendary critic, Stefan Kisielewski attacked the composer’s pathos and solemnity, questioning the value of the avant-garde:

Is there no more humor, nor energy, nor play, nor variety and surprise, and no adventure in the world of music?

Grammy Win for Krzysztof Penderecki & the Warsaw Philharmonic

Krzysztof Penderecki and the Warsaw Philharmonic win a Grammy for the first album of the Penderecki conducts Penderecki series. This is Penderecki’s fourth Grammy Award.#music#cultureRead more

Composing

I often spend more than a dozen hours a day on a score, regardless of where I am, in Poland or overseas.

The composer is said to be able to concentrate in any place at all. His first wife studied the piano and he was distracted by the sound of the instrument, so he would leave the house… to work in a crowded café. It was called the Jama Michalikowa and he always chose the same table and, as legend has it, he wrote everything on paper napkins.

These days, he is not even distracted by his grandchildren, who scribble on his sheets as he is composing. He says that his favourite place to write is probably the seaside. The Baltic landscape accompanied him as he created the noisy Polymorphy and later became an inspiration for Stabat Mater.

Szymanowski Was Also A Giant Of His Era: An Interview with Szymon Nehring

A finalist of the 17th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw (2015) and winner of the 15th Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition in Tel Aviv (2017), Szymon Nehring is one of the most talented and promising pianists of the young generation in Poland. Culture.pl’s Filip Lech had the opportunity to sit down with him.#musicRead more

Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima (or 8’37”)

Penderecki composed a piece which was meant to rebel against the dominating trends of the 1950s avant-garde and wrote ‘8’37”’ on the score, as this is how long the interpretation of the piece should be. But after listening to it, he changed the title to Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima and sends a letter with the score to the mayor of Hiroshima:

May this threnody express my deep belief that the sacrifice of Hiroshima will never be forgotten and lost, and Hiroshima will become a symbol of brotherhood between people of good will.

Others suggest that Penderecki changed the title in order to avoid accusations of overt formalism and to diminish a potentially scandalous character of the piece’s performance.

The young critic Jan Topolski described Penderecki’s Threnody in the following words:

The nearly nine-minute threnody begins with a cluster of all kinds of instruments, in the highest register and after about minute and a pause it gives way to aleatoric figures (…). In the fifth minute rare structures of an even more violent character emerge – the knocking on the box, playing on the bridge become clearer. Finally the last two minutes of the Threnody are once again a cluster in its full form, with a play on turning the volume up and down, and an added tremolo and change of registers.

Conductors and instrumentalists who saw the Threnody’s score looked at the composer as if he was a madman and refused to perform his piece. The first interpretations of it required numerous negotiations and explanations of his ideas, as well as instructions of how it should be played. The planned performances in Rome and Koln were delayed. Interestingly, the passion and engagement of every ensemble that has performed the Threnody grew each time they tackled the challenge.

The package containing the original score of the Threnody was lost on its way to the German publisher and Penderecki had to reconstruct it from memory. Later, it turned out that it was kept by the customs service, who suspected it contained some secret plots of building an atomic bomb or, at least, some army secrets of the Warsaw Pact. A deep analysis by the services proved that it was only notes and, in the end, the package finally made it to its addressee. What is fascinating in this story is that when Penderecki compared the two scores – the original and the one that he reconstructed from memory – they turned out to be identical.

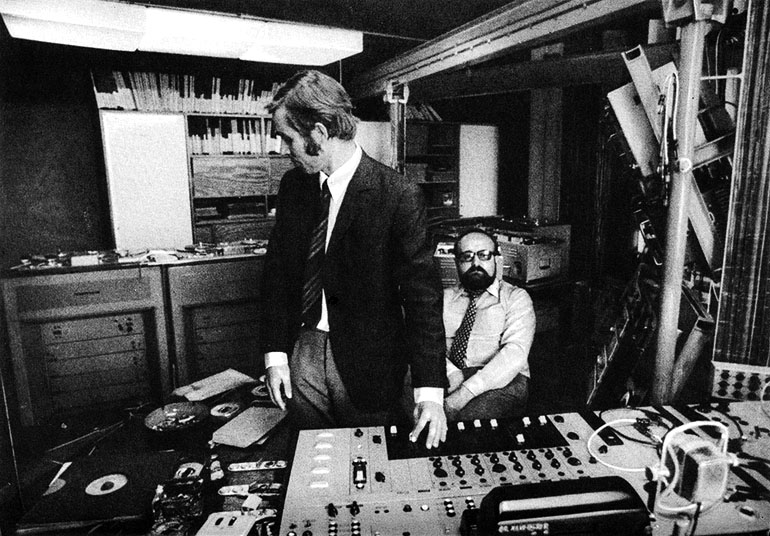

Polish Radio Experimental Studio

Penderecki is usually associated with traditional instruments but between 1958 and 1962 he also explored electronic music. Thanks to Józef Patkowski, he was granted access to the arsenal of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio in Warsaw.

In the ‘black room’ (as its headquarters were popularly called) on Malczewski Street, he met a young sound engineer, his contemporary Eugeniusz Rudnik, with whom he quickly made friends. Rudnik turned out to be an irreplaceable buddy, but also the de facto musical realiser of Penderecki’s ideas. The latter – though aware of the possibilities for experimentation afforded by the studio – at first kept his distance from it. But he came to create numerous soundtracks for film and theatre, a radio opera and more there/

Having suffered an electric shock in his youth, Penderecki had a fear of electricity, so he stayed far away from tape recorders. It was Rudnik who was his guide in the world of electronics. The sessions with Rudnik were of colossal significance to his scores from the 1960s. He transferred his experiences – with multitracks, oscilloscopes, rough montage, electronic voice transformations, and sound processing of acoustic instruments – to his writing of works such as Threnody, Polymorphia, De Natura Sonoris and Passion.

EXPERIMENTAL

Discover the Iron Curtain’s unlikeliest music haven and the people who made it happen#stories from the eastern westRead more

The Holocaust

Memories of Jews in a pre-war Poland keep surfacing not only in the klezmer motifs of Penderecki’s compositions but also in a constant reliving of the Holocaust. In 1963, Penderecki organised a naturalistic radio show, Brygada Śmierci (Death’s Brigade), based on the text by Leon Weliczker, a member of the Nazi Sonderkommando that erased traces of genocide. Weliczker was one of the Jewish prisoners incorporated into the unit by force, and after his lucky escape, he preserved his diary from the time.

The premiere performance of Brygada Śmierci was staged a year later in Warsaw, with the legendary Tadeusz Łomnicki reading the text. Two lights were placed on the stage, one a dead-blue colour, the other a screaming red. Weliczker’s text is a truly shocking testimony of the Holocaust – completely emotionless and terrifyingly detailed. Penderecki decided to use it without any modifications, only adding sound effects that were created at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio with Patkowski.

I am surprised that an artist of Penderecki’s format decided to mix, in this way, realistic documentation with an attempt at an acoustic soundtrack, which immediately makes one think of an art piece. Art ends where true realism begins.

Such was the commentary by Zygmunt Mycielski, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz added:

This thing, performed in front of a concert audience, seated in a warm auditorium on comfortable chairs seemed to addres the worst of human instincts

Another significant and less controversial representation of the Holocaust in Penderecki’s work is the piece Kaddish, with the dedication ‘To the Abrahms of Łódź who wanted to live. To the Poles who saved Jews.’

When writing music for the Kaddish, I evoked the prayers that were sung in Eastern Galicia, Ukraine and Romania. I was advised by my late friend, Boris Carmeli. Before dying, in mid-July, he passed on his remarks, he corrected the accents. He would sing me various melodies that were sung by his grandfather, thus they had to be at least as old as the mid-19th century.

How Would Klezmer Sound, If There Had Been No Holocaust: An Interview with Jarosław Bester

An interview with Jarosław Bester, founder of the Bester Quartet (formerly the Cracow Klezmer Band) – the band that heralded a new wave of Jewish music in Poland.#music#cultureRead more

New Eternal Rhythm Orchestra

In 1971, the Donaueschinger Musiktage festival brought together an exceptional orchestra, whose cast included the biggest stars of free jazz from Europe and America: Peter Brotzmann, Willem Breuker, Paul Rutherford, Han Bennink, Terje Rypdal, Kenny Wheeler, with Poland represented by Tomasz Stańko. The ensemble was conducted by Don Cherry and maestro Penderecki. They performed three compositions. Two of them were written by Cherry (Hummus – The Life Exploring Force and the Sima Rama Encores, based on Hindu music), and one was authored by Penderecki – Actions For Free Jazz Orchestra.

Krzysztof Penderecki never focused on composing film soundtracks but we are nonetheless able to hear his work in many films, such as Stanley Kubrick’s Shining, Friedkin’s The Exorcist and the Quay Brother’s Mask. In each case, it was the directors who were fascinated with the plasticity of his music and asked to employ it in their pictures.

He also composed the music to The Saragossa Manuscript, directed by Wojciech Jerzy Has, at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio – disturbing electroacoustic sounds are interspersed here with fragments of stylised early music.

Top 10 Creepiest Soundtracks by Polish Composers

There is a dark side to the Polish soul. This top 10 iconic spine-chilling soundtracks shows without a doubt that Poland’s composers are undisputed masters of music more nightmarish than Polish spelling itself.#music#filmRead more

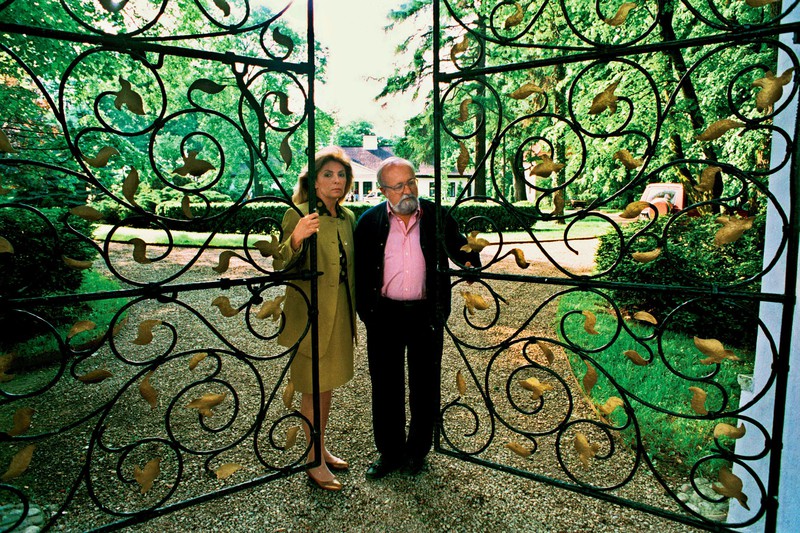

Life partner

The person responsible for the life maestro Penderecki leads today is his second wife, Elżbieta. He first met her when she was 10 years old. She was the daughter of cello player Leon Solecki, a friend of the young Penderecki in the beginnings of his career as a composer. Elżbieta took piano classes with Penderecki’s first wife. Maestro has almost no memory of Elżbieta from this time, and she remebers that he was not nice to her at all then. But everything changed during a summer vacation in by the Polish seaside in Jurata.

In an interview with Liliana Śnieg-Czaplewska, Penderecki said:

When a man falls in love, he loses his head, he pays practically no attention to anything and doesn’t analyse. Since I fell in love with Elżbieta, other women ceased to exist for me. Of course, before, like any young man, I was a bit of a ladies’ man.

Today, it is very difficult to imagine what Penderecki’s oeuvre would look like without the presence of Elżbieta Penderecka. She handles all the formalities related to being such a prominent musician: she answers his correspondence, is responsible for planning concerts and, for his 80th birthday, she organised an entire festival in his honour.

Resurrection

In 2002, Penderecki once again shocked audiences, or more precisely, he divided them. The performance of his piano concerto entitled Resurrection – written by the composer in response to the 9/11 attacks – was booed, with many people leaving the auditorium.

In his article Love me, Pender, Jan Topolski asked:

Is the true meaning of postmodernism, in which we apparently live, equal with the notion that it suffices to sit down in a library over a music score, and cut out Rachmaninov’s strings, Mahler’s pathos (and his title!), Chopin’s figurations and passages, Ravel’s instrumentations, and harps and bells of film music and simply put them together? That’s it? It’s ready?

Maestro Penderecki himself explained the genesis of his composition in the following words:

I began working in June [2001], and after a few months I was about halfway, a kind of capriccio was formed. But after September 11th, the concept underwent a radical change. I decided to write a darker and more serious piece. I withdrew a part of the material, and went back to certain place in the structure and introduced a choral…

Traces of History in Penderecki’s Oeuvre: From Gagarin to the World Trade Centre

The works of this Polish composer are filled with historic references. It this article, we attempt to trace them out.#music#cultureRead more

Dendrology & labyrinths

Penderecki’s domain is not only music. One of his biggest passions is dendrology, the study of trees. He also specialises in planting mazes. He has created two of them so far. One huge maze takes up an area of 4000 square metres and when it grows it will be very difficult to make one’s way out.

Penderecki reveals:

In the olden times, these mazes had a tower next to them, with a guard that would guide the lost ones to the exit. I also want to raise a tower like that. I would love to sent the critics that wrote badly of me into this maze, but they would be the ones who would have to find their way out with no guide. As a punishment. A sort of purgatory.

Music Is Not for Everyone: An Interview with Krzysztof Penderecki

“Listening to classical music is like reading philosophy books”, says Krzysztof Penderecki. In the summer of 2015 he is recording his oratory works with the Warsaw Philharmonic, the National Orchestra, and the Choir of Poland.#music#culture.pl interviewsRead more

The conductor

Penderecki’s other passion is conducting – both compositions he wrote as well as ones by other composers. His adventure with conducting began by chance. The piece Actions For Free Jazz Orchestra was originally meant to be left to the instrumentalists, with no part written for a conductor. But when he arrived in Donauschingen for the rehearsals, Penderecki realised that the musicians couldn’t tackle the material he wrote on their own. First he gave them tips and instructions, but the day before the premiere performance he decided that he would conduct them.

When I conduct my own pieces I am allowed to make elements of the composition become the ideal image that I had imagined (…) only I know how the course of the my piece should unfold with time.

Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933): Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima (1960) Krzysztof Urbański (b. 1982), conductor Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra Helsinki Music Centre, 13 March 2015

Кшиштоф Пендерецкий 1. Dies Irae Освенцим, оратория I. Lamentatio II. Apocalypsis III. Apotheosis Стефания Войтович, сопрано Веслав Охман, тенор Бернард Ладыш, бас Хор и оркестр Краковской филармонии Дирижёр Генрих Чиж запись 1967 г.

Krzysztof Penderecki Dies Irae

Auschwitz, oratorio

I. Lamentatio

II. Apocalypsis

III. Apotheosis

Stefania Voitovich, soprano

Wieslaw Ohman, tenor

Bernard Ladysh, bass

Choir and Orchestra of the Krakow Philharmonic

Conductor Henrikh Chizh

recorded 1967

Krzysztof Penderecki’s opera “Paradise Lost,” one of the largest musical efforts of the last half-century. The audience, many of whom expected to hear music of dissonant, grating sounds, interspersed with violent screams from the chorus, was surprised to hear music of vivid imagination, but music that did not violate their ideas of great choral and orchestral textures. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv… Krzysztof Penderecki: Paradise lost (1978) Atto I, parte 1 00:00 Krzysztof Penderecki: Paradise lost (1978) Atto I, parte 2 50:49 Krzysztof Penderecki: Paradise lost (1978) Atto II, parte 1 1:32:12 Krzysztof Penderecki: Paradise lost (1978) Atto II, parte 2 2:24:51 All rights reserved to Krzysztof Penderecki and its affiliates.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_m3DbExkUk0

Krzysztof Penderecki, Metamorphosen: Allegro ma non troppo (ex). Anne-Sophie Mutter / LSO