Inspirée par le bouddhisme, la tradition tibétaine millénaire propose une approche de la médecine à mille lieues des pratiques occidentales.

Parvenir à l’harmonie du corps, de l’esprit et de l’âme, telle est la philosophie de la médecine tibétaine. Intimement liée au bouddhisme, cette approche thérapeutique est pratiquée jusque dans le nord de l’Inde, et tout particulièrement à Dharamsala, dans l’Himachal Pradesh, terre d’accueil de nombreux Tibétains en exil. Découverte de cet art millénaire au travers des gestes de plusieurs praticiens, dont l’un des médecins personnels du dalaï-lama.du dalaï-lama.

https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/086117-014-F/geo-reportage-la-medecine-tibetaine-l-art-de-guerir/

Some History

The Tibetan medical system is one of the world’s oldest known medical traditions. It is an integral part of Tibetan culture and has been developed through many centuries. We believe that the origin of the Tibetan medical tradition is as old as civilization itself.

Because humankind has depended on nature for sustenance and survival, the instinctive urge to health and accumulated knowledge has guided us to discover certain remedies for common ailments from natural sources. For example, applying residual barley from chang (Tibetan wine) on swollen body parts, drinking hot water for indigestion, and using melted butter for bleeding are some of the therapies that arose from practical experiences and gradually formed the basis for the art of healing in Tibet. The Tibetan medical heritage is based on the book of the Four Tantras (rGyud-bZhi), which remains the fundamental medical text even today.

The era from the beginning of human civilisation to the advent of Buddhism in Tibet, can be termed as the pre-Buddhist era. During that time Bon tradition flourished in Tibet and Bon medical practice influenced and enriched the existing Tibetan Medical knowledge and practice. It has been clearly mentioned in a Bon text titled “Jam-ma tsa-drel” that around 200 B.C., (during the emergence of the first Tibetan King Nyatri Tsenpo) there lived twelve scholars of Bon tradition including a medical scholar who treated diseases through medication and therapy. This indicates that Tibetans practiced medicine and there were Tibetan physicians even prior to the advent of Buddhism in Tibet.

Buddha Shakyamuni (961-881 B.C.,) (according to Phuglug Tradition of Tibetan Astrology)

Shakyamuni Buddha was born in circa 961 B.C., and he lived till 881 BC. During his life time he taught Buddha Dharma (popularly known as Buddhism). Buddhism came to Tibet during the reign of King Thothori Nyantsen (245-364 A.D.,) (according to gSo-rig Kuns ‘Dus ). The Buddhist teachings gradually spread and were assimilated into every part of Tibetan culture, becoming Tibet’s state religion. The philosophy of Tibetan Medicine also got motivated by it and the influences are clearly visible in rGyud-Zhi (the principal Tibetan medical text). The incorporation of Buddhist views of the four immeasurable thoughts and six perfections in the prerequisite conditions of Tibetan physicians are testimony of these influences.

Lha Thothori Nyantsan (245-364 A.D.,) (according to gSo-rig Kuns ‘Dus)

The Indian physicians Biji Gaje and Bila Gazey (according to Yuthok Sernying kyi Namthar) were born to rNga-Chenpo, the King of Yul Pema Nyingpo, and his two wives, one the daughter of a drum maker and the other the daughter of a bell maker. The mothers offered ten drums and ten bells to the Mahabodhi Stupa of Vajrasana and made prayers for their children’s success in benefitting sentient beings. When the boy and girl grew older, they requested their parents to let them learn the Science of Healing. After getting permission, they went to Taxilla in present day Pakistan and studied medicine under the great Physician Atreya. Afterwards, they travelled throughout India and also visited China, Nepal and East Turkistan (which is now under China and called Xinjiang Autonomous Region). They also received medical teachings from another great physician, Kumara Jivaka, at Magadha.

https://www.men-tsee-khang.org/tibmed/tibhistory.htm

The Fundamental Treatise rgyud-bzhi

The fundamental medical treatise, the rGyud-bZhi, is comprised of four sections, usually known as the Four Tantras:

The Root Tantra

The Explanatory Tantra

The Oral Instruction Tantra and

The Last/Subsequent Tantra.

The complete text encompasses 5900 verses which are grouped into 156 chapters.

The following is a short description of the contents of this treatise, which lists the different topics discussed in Tibetan medicine and illustrates the lucid and systematic presentation of the instructions.

The Root Tantra

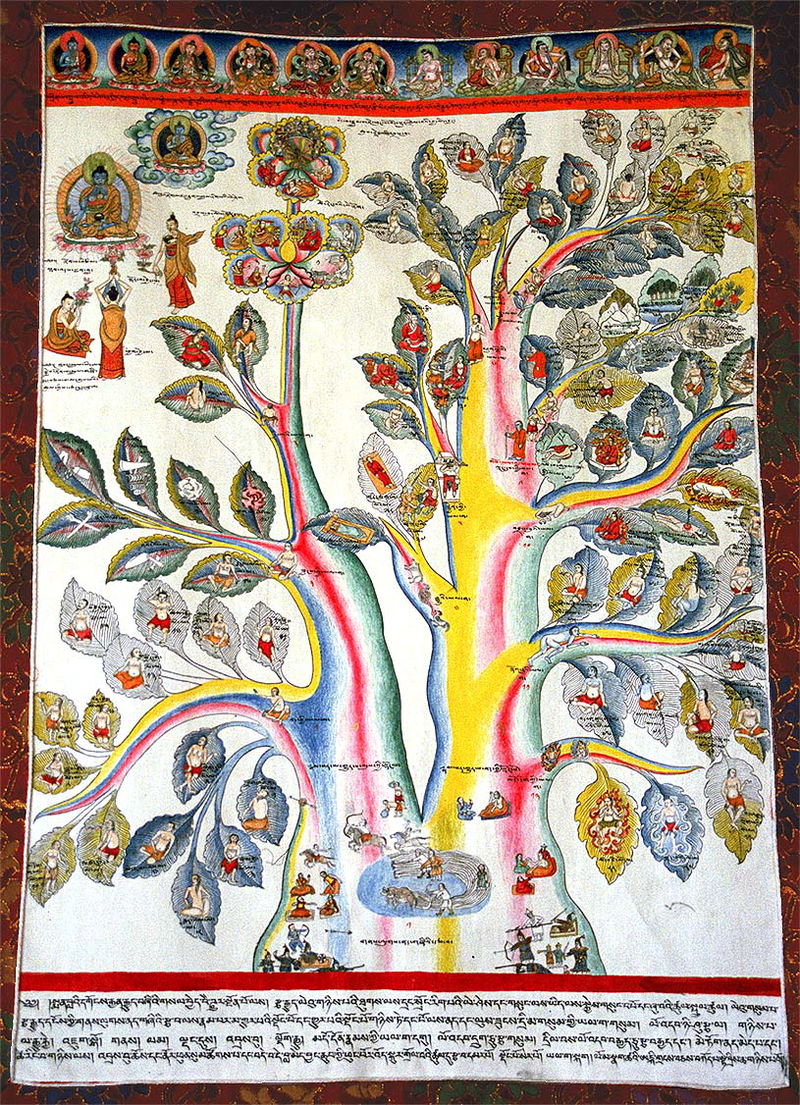

The first section, the Root Tantra, is comprised of six chapters giving a brief outline of the whole text and comparing the medical system with a tree. Three roots sprout into nine stems, which branch out into 47 branches bearing 224 leaves. The nine stems represent the nine sections of medical science, the branches stand for general information and the leaves illustrate the details.

The First root

The first root explains the human organism and its functioning and encompasses two stems, which stand for the healthy and the sick body. The healthy body is represented by three branches and 25 leaves, the sick body by nine branches and 63 leaves. The first stem, the healthy body, bears three branches. One of the branches represents the three humours, the other represents bodily constituents (nutritional essence, blood, muscle tissue, fat or fatty tissue, bones, marrow and regenerative fluid) and the third branch the three excretions of the body (faeces, urine and perspiration).

Furthermore, the first stem bears two flowers standing for health and long life and three fruits representing religion, wealth and happiness.

The second stem represents the sick body. This section deals with the three causes, the four conditions, the six different entrances, the locations and the fifteen pathways of the diseases. The association of advancement of diseases with the patient’s age, the seasons and the place where the patient resides is also discussed. Furthermore, the nine fatal disorders, the twelve contraindications due to inappropriate treatment and the condensation of all the disorders into hot and cold nature are also stated.

The root of Physiology and Pathology

Tibetan concept of health and disease has been illustrated as a tree with two stems. The first stem deals with the healthy body. It has three branches, 25 leaves, two flowers and three fruits. The first branch bears 15 leaves representing the three humours and their five types. These are depicted in the three different colours blue, yellow and white signifying the humours rLung, mkhris-pa and bad kan, respectively.

The second branch has seven leaves representing the seven bodily constituents.

The third branch bears three leaves, which stand for the three bodily excretions. The two flowers stand for a healthy and long life and ultimately serve as the basis for attaining the three fruits: spiritual accomplishment, wealth and happiness.

The second stem deals with the diseased body. It comprises of nine branches and 63 leaves. The first branch has three leaves, which stand for the three specific distant causes of disorder: attachment, hatred and closed mindedness. The second branch bears four leaves depicting the four conditions that trigger disorders: seasonal changes, evil spirit influences, diet and behaviour. The third branch has six leaves representing the six areas of inception of diseases. The fourth branch possesses three leaves showing the main locations of the three humours. The fifth branch has 15 leaves, which illustrate the pathways of the humours. The sixth branch has nine leaves representing the humoral diseases in relation to age, place of occurrence, maturation period and seasonal changes. The seventh branch has nine leaves signifying the nine fatal disorders. The eighth branch shows 12 leaves depicting the twelve contraindications due to inappropriate treatment. The ninth and the last branch has two leaves, which represent hot or cold disorders.

The Second root

The second root informs about the methods of diagnosis, the examination of the tongue and urine, the pulse diagnosis and the questioning of the patient regarding the symptoms of the disease, the way of living, etc.

The root of Diagnosis

This illustration displays three stems and depicts the three main diagnostic techniques used by Tibetan physicians: pulse reading, urine analysis and interrogation. The first stem deals with visual observation methods. It is divided into two branches; the first branch stands for observation of the tongue and the other branch for urine analysis. These branches possess three leaves each, showing that each of the three humours has a different effect on the patient’s tongue and urine, which can be visually detected by the physician.

The second stem depicts the pulse analysis in three branches each comprising of a single leaf symbolising the different pulse natures of the three humours.

The third stem deals with the method of interrogation. It consists of three branches with 11 blue leaves relating to rlung disorders, seven yellow leaves relating to mkhris-pa disorders and 11 white leaves to bad-kan disorders. These colours stand for the different ways of inquiring used to identify the humoral diseases and their symptoms as well as to determine their remedies.

The Third root

This root deals with therapeutic methods, diet, behaviour, medical preparations and external treatments.

The root of Treatment

This picture shows the methods of treatment used in the Tibetan system of medicine. The root of treatment develops into four stems symbolising diet, behaviour, medication and external therapy. These treatments are generally used in combination depending on the nature of the person and the disease involved.

The first stem stands for diet treatment, which has six branches. The first two branches with ten and four blue leaves, respectively, show the diet and the drink best suited to treat rlung disorders. The third and fourth branches with seven and five yellow leaves, respectively, stand for the diet and drink suitable for mkhris-pa disorders and the fifth and sixth branches with six and three white leaves, respectively, stand for the diet and drink recommended for bad-kan disorders.

The second stem illustrates behavioural treatment. It has three branches with two leaves each representing the behaviours beneficial for the three humours.

The third stem depicts the different medications. It has a total of 15 branches and 50 leaves. The first six branches each bear three leaves. These refer to the tastes and medicinal qualities favourable for treating rlung, mkhris-pa and bad-kan disorders, which are shown as blue, yellow and white leaves, respectively.

The seventh to the twelfth branches bear a total of 23 leaves representing different medicinal preparations: broth and medicinal butter, decoctions and powders, pills and specific medicinal powders. The type of preparation prescribed depends on the afflicted humour. In addition to the above medications, there are three different branches symbolising medicinal preparations with a cleansing effect: enemas, purgatives and emetics used respectively for rlung, mkhris-pa and bad-kan disorders. They are represented by three blue leaves on the thirteenth branch, four yellow leaves on the fourteenth and two white leaves on the fifteenth branch. The fourth stem stands for external therapies, which are generally used as a last resort after all other treatments fail. It consists of three branches. The two blue leaves on the first branch portray the external therapy used to treat rlung disorders. The three yellow leaves on the second branch stand for external therapies used to fight mkhris-pa disorders and the two white leaves on the third branch signify external therapies used on bad-kan disorders.

The Explanatory Tantra

The second Tantra, the Explanatory Tantra, encompasses 31 chapters and is concerned with the life cycle (conception, childbirth, functioning of the three humours and signs of death), causes, conditions and classification of the diseases. It specifies the properties of medicinal ingredients and explains in detail diet, behaviour and the rules for maintaining health, etc. It also contains a code which the physicians should up-hold in conducting his profession.

The Oral Tradition Instruction Tantra

The third Tantra, the Oral Tradition Tantra, consists of 92 chapters which mainly teach the 101 disorders of the three humours indicating their causes, conditions, symptoms and methods of therapy.

The Subsequent / Last Tantra

The fourth tantra, the Last Tantra, is comprised of 27 chapters, which deal with diagnosis (such as urine analysis and pulse reading), pacifying medicinal ingredients and their preparations (pills, powders, syrups, medicinal butters, etc.) evacuative medications (purgatives and emetics) and additional treatments (moxibustion, golden-needle therapy) which are applied when all other medicinal preparations have failed to cure the patient.

https://www.men-tsee-khang.org/tibmed/med-treatise.htm

Traditional Tibetan medicine (Tibetan: བོད་ཀྱི་གསོ་བ་རིག་པ་, Wylie: bod kyi gso ba rig pa), also known as Sowa-Rigpa medicine, is a centuries-old traditional medical system that employs a complex approach to diagnosis, incorporating techniques such as pulse analysis and urinalysis, and utilizes behavior and dietary modification, medicines composed of natural materials (e.g., herbs and minerals) and physical therapies (e.g. Tibetan acupuncture, moxabustion, etc.) to treat illness.

The Tibetan medical system is based upon Indian Buddhist literature (for example Abhidharma and Vajrayana tantras) and Ayurveda. It continues to be practiced in Tibet, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Ladakh, Siberia, China and Mongolia, as well as more recently in parts of Europe and North America. It embraces the traditional Buddhist belief that all illness ultimately results from the three poisons: ignorance, attachment and aversion. Tibetan medicine follows the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths which apply medical diagnostic logic to suffering.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traditional_Tibetan_medicine

Die Tibetische Medizin (tibetisch: བོད་སྨན Wylie: bod sman) auch Traditionell Tibetische Medizin (TTM) (tibetisch: བོད་ཀྱི་གསོ་བ་རིག་པ་ Wylie: bod kyi gso ba rig pa) ist ein in Tibet entwickeltes Heilsystem, das vorwiegend in den Ländern und Regionen des Hochlands von Tibet verbreitet ist. Über ihren Ursprung gibt es verschiedene Legenden.[1]Als Basistexte der tibetischen Medizin gelten das „Gyüshi“ (tibetisch: rgyud bzhi; „Vier Tantras“, „Vier Wurzeln“)[2] von Yuthok Yönten Gönpo (dem Älteren) (tibetisch: g.yu thog (rnying ma) yon tan mgon po; 708–833) und das „Yuthok Nyingthig“ (tib.: g.yu thog snying thig; „Herzessenz von Yuthok“) von Yuthok Yönten Gönpo (dem Jüngeren) (tibetisch: g.yu thog (gsar ma) yon tan mgon po; 1126–1202). Im 17. Jahrhundert wurden Texte des „Gyüshi“ unter dem Titel „Der blaue Beryl“ erstmals zu Ausbildungszwecken illustriert und von Desi Sanggye Gyatsho kommentiert.

Tibetaanse geneeskunde is een traditioneel geneeswijzesysteem dat de Indiase ayurveda als voornaamste basis heeft. De ziekteleer en in het bijzonder de voorstelling, dat de belangrijkste oorzaken van ziekte terug te voeren zijn op drie beperkingen van de menselijke geest (begeerte, aversie en onwetendheid), rusten op de leer van Gautama Boeddha. De werking van de Tibetaanse geneeskunde is niet wetenschappelijk bewezen.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tibetische_Medizin

Tibetaanse geneeskunde wordt niet alleen in de huidige Chinese provincie Tibet toegepast, maar ook in bijvoorbeeld de aangrenzende provincies Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan, de Indiase deelstaten Ladakh en Sikkim en de buurlanden Bhutan en Nepal. Na de Tibetaanse diaspora in de jaren 50 van de 20e eeuw breidde de toepassing van de Tibetaanse geneeskunde zich uit over de wereld, in het bijzonder over India, Europa en Noord-Amerika.

De Vier medische tantra´s

De Tibetaanse geneeskunde zoals die nu bekendstaat, werd voor het eerst beschreven in de Vier medische tantra’s. Er zijn verschillende tradities ten aanzien van de herkomst van het werk. Wetenschappelijk onderzoek heeft vastgesteld dat de tekst uit de twaalfde eeuw dateert. De belangrijkste auteur dan wel samensteller van het werk is Yutog Sarma Yönten Gönpo (‘de jongere’). Een deel van de tekst is ontleend aan Indiase medische verhandelingen, zoals een deel van de Ayurveda, die in de elfde eeuw al door Rinchen Zangpo waren vertaald in het Tibetaans. De Vier medische tantra’s is het klassieke leerboek waarin alle beschikbare kennis van dat moment van de Tibetaanse geneeskunde werd samengevat. Het is tot op heden de basis van die geneeskunde.

Belangrijkste kenmerken

De basiseigenschappen van het lichaam in de Tibetaanse geneeskunde zijn de dosha’s, dat vertaald ‘fouten’, ‘vlekken’ of ‘onbalans’ betekent. Tot de dosha’s worden alle fouten als gevolg van een verstoring van de balans/levensritme dat prana wordt genoemd gerekend. Prana ontstaat door de samenkomst van Shiva (=yang) en Parvati (=yin). Een samenkomst van een ongelijke hoeveelheid van deze twee veroorzaakt onbalans.

Er wordt gerekend dat iemand die zich niet in de normtoestand bevindt, het lichaam schade berokkent. Tegengesteld is iemand die in harmonie leeft, gezond. Wanneer deze lichaamsprincipes zich in een toestand van een tekort of overvloed bevinden, dan storen ze elkaar en is volgens de filosofie ziekte het gevolg.

Elk van de lichaamsenergieën treedt in vijf verschillende vormen met verschillende functies en lokalisaties op. Er is een gedifferentieerd systeem van lichaamskanalen, waarin de verschillende vormen van energie en vloeibare stoffen getransporteerd worden, wat de Tibetaanse geneeskunde een complex geneessysteem maakt met een overeenkomstige diagnostiek.

De vijf elementen: vuur, aarde, metaal, water en hout

De drie dosha’s zijn actieve verdichtingen van de vijf grote elementen: metaal, hout, water, vuur en aarde. Belangrijk in de filosofie is het harmonische evenwicht tussen de elementen, waarbij wordt uitgegaan dat het met voeding in balans blijft. Ze hebben als taak deze elementen in de microkosmos van het lichaam te beïnvloeden:Wind – ‘energie van beweging’Rlung, Sanskriet: vayu, vatta, staat voor het bewegelijke element van in lichaam en geest en is bij alle fysiologische processen betrokken die naar hun aard dynamisch zijn. Rlung is de drijvende kracht achter de vegetatieve functies ademhaling, hartslag en peristaltiek. Rlung staat echter ook voor zintuiglijke waarneming en psychische activiteit.Gal – ‘vuur van het leven’Mkhrispa of tripa, Sanskriet: pitta, staat voor de verschillende soorten van warmte in het lichaam en neemt aan de stofwisseling deel, in het bijzonder aan de spijsvertering, en wordt met het koken van voeding vergeleken.Slijm – ‘het vloeibare element’Badkan, Sanskriet: Kapha, staat voor alle factoren van vloeibaarheid in het lichaam en vervult functies van mechanische natuur: cohesie, ondersteuning, smering, enz.

Vier nobele waarheden

In het boeddhisme wordt gesproken van vier nobele waarheden:

- De eerste nobele waarheid is de waarheid van het lijden, het feit, dan geluk voortdurend daarnaartoe verdwijnt. Geboorte, ouderdom, ziekte en dood is lijden. Alles dat we hebben is aan de onbestendigheid onderworpen.

- De tweede nobele waarheid toont de oorzaak, ook wel de drie giffen van onophoudelijke lijden:

- Hechting, begeerte en verlangen

- Woede, haat en agressie

- Onwetendheid en verblinding

- Het subject-objectdualisme of het vasthouden aan de voorstelling van een duurzaam, vooral gescheiden bestaande Ich (ti-mug) is de basisverblinding, waar alle andere uit voortkomen. Volgens de boeddhistische filosofie, psychologie en oosterse geneeskunde is het vasthouden aan het Ego de oorzaak van alle lijden en ziektes.

- De derde nobele waarheid gaat over het eindigen van het lijden, door wortel van het lijden eruit te trekken door middel van de tegengiffen medeleven, meditatie en wijsheid.

- De vierde nobele waarheid luidt, dat er een pad is die naar het beëindigen van het lijden leidt. Het pad naar de bevrijding bestaat uit de uitoefening van vrijgevigheid, zedelijkheid, geduld, inspanning, concentratie en wijsheid.

Het boeddhistische geneessysteem gaat ervan uit, dat het lijden inherent met de mens is verbonden. Ziekte wordt niet als een vreemde grootheid gezien die het lichaam van buiten aantast, maar als een principe dat in wezen deel uitmaakt van het leven zelf.

De volgende tabel toont de geneeskundige overeenkomsten met betrekking tot de vier waarheden:

| Vier nobele waarheden | Westerse geneeskunde | Tibetaanse geneeskunde | Leer van Gautama Boeddha |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Waarnemen van het lijden | het leven | het lijden | |

| 2. Oorzaak van het lijden (etiologie) | uiterlijke, somatische factoren | onbalans van lichaamsprincipes | begeerte, haat, woede, verblinding |

| 3. Opheffing van het lijden (therapie) | eliminatie somatische oorzaken | herstel innerlijk evenwicht | tegengiffen: medeleven, meditatie en wijsheid |

| 4. Pad, therapeutische werkwijze | geneesmiddelen, chirurgie, radiotherapie | geneesmiddelen, voeding, levenswijze | het Achtvoudige Pad |