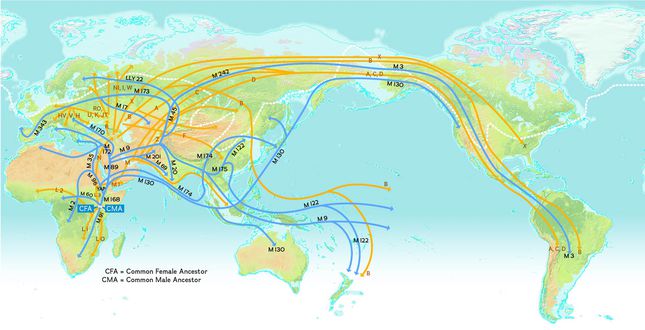

Map of human migration out of Africa by haplogroups: Haplogroups are sets of similar closely linked DNA sequences (haplotypes) inherited together. Y-DNA haplogroups are indicated by the blue lines, while mitochondrial DNA is indicated by the yellow lines. Since this map was published in 2008, the M3 mutation has been grouped under the larger haplogroup Q. (So, Q-M3.)

When humans first ventured out of Africa some 60,000 years ago, they left genetic footprints still visible today. By mapping the appearance and frequency of genetic markers in modern peoples, we create a picture of when and where ancient humans moved around the world. These great migrations eventually led the descendants of a small group of Africans to occupy even the farthest reaches of the Earth.

Our species is an African one: Africa is where we first evolved, and where we have spent the majority of our time on Earth. The earliest fossils of recognizably modern Homo sapiens appear in the fossil record at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia, around 200,000 years ago. Although earlier fossils may be found over the coming years, this is our best understanding of when and approximately where we originated. Learn more about Early Human Milestones

According to the genetic and paleontological record, we only started to leave Africa between 60,000 and 70,000 years ago. What set this in motion is uncertain, but we think it has something to do with major climatic shifts that were happening around that time—a sudden cooling in the Earth’s climate driven by the onset of one of the worst parts of the last Ice Age. This cold snap would have made life difficult for our African ancestors, and the genetic evidence points to a sharp reduction in population size around this time. In fact, the human population likely dropped to fewer than 10,000. We were holding on by a thread. Learn more about Migratory Crossings

Once the climate started to improve, after 70,000 years ago, we came back from this near-extinction event. The population expanded, and some intrepid explorers ventured beyond Africa. The earliest people to colonize the Eurasian landmass likely did so across the Bab-al-Mandab Strait separating present-day Yemen from Djibouti. These early beachcombers expanded rapidly along the coast to India, and reached Southeast Asia and Australia by 50,000 years ago. The first great foray of our species beyond Africa had led us all the way across the globe. Learn more about the Migration to Australia

Slightly later, a little after 50,000 years ago, a second group appears to have set out on an inland trek, leaving behind the certainties of life in the tropics to head out into the Middle East and southern Central Asia. From these base camps, they were poised to colonize the northern latitudes of Asia, Europe, and beyond. Learn more about Migration Mysteries

Around 20,000 years ago a small group of these Asian hunters headed into the face of the storm, entering the East Asian Arctic during the Last Glacial Maximum. At this time the great ice sheets covering the far north had literally sucked up much of the Earth’s moisture in their vast expanses of white wasteland, dropping sea levels by more than 300 feet. This exposed a land bridge that connected the Old World to the New, joining Asia to the Americas. In crossing it, the hunters had made the final great leap of the human journey. By 15,000 years ago they had penetrated the land south of the ice, and within 1,000 years they had made it all the way to the tip of South America. Some may have even made the journey by sea. Learn more about the Bridge to the New World

The story doesn’t end there, of course. The rise of agriculture around 10,000 years ago—and the population explosion it created—has left a dramatic impact on the human gene pool. The rise of empires, the astounding oceangoing voyages of the Polynesians, even the extraordinary increase in global migration over the past 500 years could all leave traces in our DNA. There are many human journey questions waiting to be asked and answered. What stories are waiting to be told in your own DNA? Learn more about The Development of Agriculture

https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/human-journey/

It’s tough to know what happened on Earth thousands of years before anyone started writing anything down. But thanks to the amazing work of anthropologists and paleontologists like those working on National Geographic’s Genographic Project, we can begin to piece together the story of our ancestors. Here’s how early humans spread from East Africa all around the world.

Human migration is the movement by people from one place to another, particularly different countries, with the intention of settling temporarily or permanently in the new location. It typically involves movements over long distances and from one country or region to another.

Historically, early human migration includes the peopling of the world, i.e. migration to world regions where there was previously no human habitation, during the Upper Paleolithic. Since the Neolithic, most migrations (except for the peopling of remote regions such as the Arctic or the Pacific), were predominantly warlike, consisting of conquest or Landnahme on the part of expanding populations. Colonialism involves expansion of sedentary populations into previously only sparsely settled territories or territories with no permanent settlements. In the modern period, human migration has primarily taken the form of migration within and between existing sovereign states, either controlled (legal immigration) or uncontrolled and in violation of immigration laws (illegal immigration).

Migration can be voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary migration includes forced displacement (in various forms such as deportation, slave trade, trafficking in human beings) and flight (war refugees, ethnic cleansing).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_human_migration

Völkerwanderung

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%B6lkerwanderung

Meer dan 85.000 jaar geleden zorgde een mutatie op chromosoom 11 ervoor dat voorouders van de mens minder afhankelijk werden van vis in hun dieet.

Volgens Floyd Chilton, hoogleraar aan de universiteit Wake Forest Baptist, vormde vis met daarin lange meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren een belangrijk onderdeel van het voedsel van de oermens. Grote hoeveelheden van die vetzuren zijn namelijk nodig voor de ontwikkeling van het brein. Toen dankzij een mutatie het menselijk lichaam zelf kortere onverzadigde vetzuren kon omzetten in langere, verdween die afhankelijkheid van vis en schaaldieren.

Linolzuur

Volgens Chilton, die het onderzoek uitvoerde met collega’s van Johns Hopkins University en de University of Washington, was de moderne mens door die voedselafhankelijkheid gekluisterd aan zijn oorspronkelijke woongebied in Centraal-Afrika. De moderne mens verscheen ongeveer 180.000 jaar geleden, maar bleef daarna bijna 100.000 jaar in hetzelfde gebied wonen. In het vakblad PLoSONE beschrijven de onderzoekers hoe ze met DNA-gegevens uit het 1000 Genomes Project en de database Human Genome Diversity Panel konden achterhalen sinds wanneer de moderne mens uit plantaardige vetzuren zoals linolzuur en linoleenzuur de benodigde lange onverzadigde vetzuren kon maken. Dat zijn vetzuren met een lengte tot wel 24 koolstofatomen en tot wel zes onverzadigde bindingen in de koolstofketen.

.jpg)

Een wereldkaart toont de verspreiding van mutaties op chromosoom 11 die zorgen voor omzetting van onverzadigde vetzuren.

De onderzoekers bestudeerden het genetisch materiaal van ruim 2000 mensen afkomstig uit meer dan 50 populaties. Ze keken naar dat deel van chromosoom 11 dat codeert voor de enzymen die nodig zijn voor de omzetting van de onverzadigde vetzuren. Uit de genetische verschillen op chromosoom 11 volgt dan het volgende scenario: vanaf 80.000 jaar geleden, wanneer er mensen leven die voor de ontwikkeling van hersenen minder afhankelijk van vis zijn, zorgt een selectiedruk voor de verspreiding van die mensen over het Afrikaanse continent.

Vishaak

Vermoedelijk migreerde een kleine groep mensen met de mutatie zo’n 40.000 tot 50.000 jaar geleden uit Afrika en verspreidde zich over de andere continenten, stellen de onderzoekers. Als mensen gemakkelijker in hun voedsel kunnen voorzien, verdwijnt de selectiedruk. Zo gaan mensen, volgens archeologisch onderzoek, 50.000 jaar geleden op grote dieren jagen. Rond 14.000 jaar geleden doen vishaak, boog en pijlen hun entree, en niet veel later volgt de domesticatie van dieren. De sociale en technische capaciteit om voedsel met voldoende lange meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren te verkrijgen, maakte de mutatie minder belangrijk.

De onderzoekers zagen bij mensen van Afrikaanse afkomst vaker genetische variaties op chromosoom 11 waardoor het lichaam plantaardige meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren omzet in andere lange vetzuren die een rol spelen bij ontstekingen. Dat verklaart waarom Afro-Amerikanen in de VS vergeleken met andere bevolkingsgroepen vaker last hebben van hoge bloeddruk, type-2-diabetes, aandoeningen aan de hartkransslagaderen, beroerte en sommige typen kanker. In een persbericht verklaart Chilton dat dit een nieuwe aanwijzing vormt voor de reden waarom allerlei etnische groepen verschillend reageren op het moderne westerse dieet.